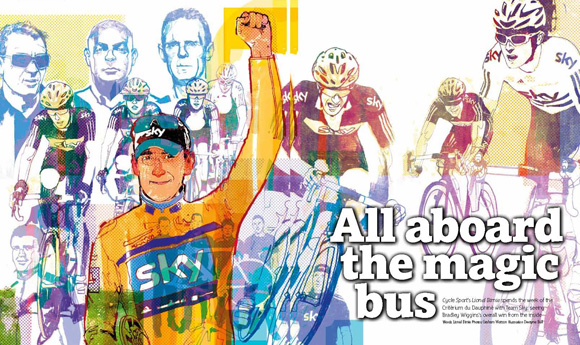

All aboard the magic bus

Cycle Sport spent a week embedded with the Sky team at the Critérium du Dauphiné, watching Bradley Wiggins win the race from the inside. This article first appeared in Cycle Sport August 2011.

Words by Lionel Birnie

Illustration by Dwayne Bell. Racing pictures by Graham Watson

***

When you watch ants go about their business, you see them all rushing hither and thither, all part of some bigger plan, all with a specific job to do. A cycling team is a little like a colony of ants - you have to get very close up to see how they work together and who does what in order to appreciate their individual roles. Cycle Sport spent a week with Team Sky at the Criterium du Dauphiné in the French Alps to see the Happy Ants do their thing, while keeping a close eye out for the appearance of any Inner Chimps.

TEAM SKY’S RULES

Written on a poster inside the bus

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

We will respect one another and watch each other's backs

We will be honest with one another

We will respect team equipment

We will be on time

We will communicate openly and regularly

If we want our helmets cleaned we will leave them on the bus

We will pool all prize money from races and distribute at the end of the year

Any team bonuses from the team will be split between riders on that race

We will give 15% of all race bonuses and prize money to staff

We will speak English if we are in a group

We will debrief after every race

We will always wear team kit and apparel as instructed in the team dress code

We will not use our phones at dinner - if absolutely required we will leave the table to have the conversation

We will respect the bus

We will respect personnel and management

We will ask for any changes to be made to the bikes (gearing, wheel selection etc) the night before the race and not on race day

We will follow the RULES

**

SATURDAY

The Best Western Alexander Fleming in Chambéry is typical of the hotels in which professional cyclists spend their working lives. It is stuck next to a roundabout on an industrial estate near an autoroute junction. There aren’t little cafés or bars buzzing with humanity nearby. Instead there’s a DIY superstore and a dreadful chain restaurant. The hotel is tidy but functional, with furniture and décor chosen by head office and staff on autopilot.

Late afternoon is giving way to early evening. The car park outside has been taken over by the Sky and Ag2r teams, who each have a fleet of vehicles positioned strategically in a land grab formation. Mechanics are working on time trial bikes for tomorrow’s prologue. The generators hum and the hoses run. If you were a guest at the hotel you might find the presence of two cycling teams dominating the car park and the dining room annoying.

Sky’s what-you-see-is-what-you-get head coach Shane Sutton is reclining in one of the armchairs in reception. He is talking to Juan Antonio Flecha. It is a surprise to see Sutton here. The previous day he’d sent a text saying he would be arriving a few days late after being struck down by a bug at the Bayern Rundfahrt race in Germany. A food poisoning outbreak is dominating the news and the Germans are blaming Spanish salad.

“I nearly didn’t make it,” he calls over. “I thought it was a dodgy cucumber.”

Sutton is not the type to be laid low for long. He has been with Bradley Wiggins every step of the way this season. He’s a mentor and a minder and at times he must feel like a babysitter too. Last year, as Wiggins wilted under the pressure of leading the multi-million pound team while trying to repeat his fourth place in the 2009 Tour de France, Team Sky battled, and failed, to keep him from derailing.

This year Sutton and Tim Kerrison, the team’s head of performance science, have been assigned to work closely with Wiggins. Sutton takes care of the mind, Kerrison works on the physical conditioning. As Sutton says, Wiggins needs to be loved, bolstered, encouraged and bollocked. The key is understanding which is necessary.

Kerrison has the appearance of a youthful university professor. Neat hair and a serious manner. He is sitting in reception, working on his laptop. To the uninitiated, the screen shows a jumble of charts and numbers but the Training Peaks software plots every effort Wiggins has made on a bicycle this year. “We really didn’t have much of a picture of Brad as an athlete,” he says. “The first job was to build up an accurate picture and then tailor his training to the demands of the event.” Every time Wiggins has ridden his bike this year, whether on the road or the turbo, in a race or training, he has recorded his power output. Kerrison, who previously led the revolution in Australian swimming, has analysed it all and knows to the watt how much work Wiggins has done.

This attention to detail and level of scrutiny might feel suffocating had Wiggins not bought into the idea.

“The bottom line is, we know what happened last year,” says Sutton. “We’re not going back over it again but we’re not repeating the same mistakes either. We don’t want to focus on the negatives and drag it all up again but basically he didn’t do the work last year. He might say he did, but we know he didn’t. If you print that, I’ll kill you.” Sutton need not worry. Later in the week, Wiggins will admit as much.

**

The room list is stuck on the wall next to the lift. Eight riders are supported by 16 staff. It is apparent that, barring disaster, this group will be the bulk of the Tour de France team. Last year the Tour team prepared in completely different ways and some arrived for the start virtual strangers. Wiggins, Michael Barry and Steve Cummings rode the Giro, Edvald Boasson Hagen and Geraint Thomas did the Dauphiné while Flecha, Simon Gerrans, Thomas Lofkvist and Serge Pauwels rode the Tour of Switzerland.

TEAM SKY RIDERS ROOM LIST

Juan Antonio Flecha & Edvald Boasson Hagen

Simon Gerrans & Christian Knees

Geraint Thomas & Bradley Wiggins

Rigoberto Uran & Xabier Zandio

STAFF

Shane Sutton – Head coach

Sean Yates – Sports director

Nicolas Portal – Sports director

Tim Kerrison – Head of performance science

Richard Freeman – Doctor

Bob Grainger – Physio

Sebastian Paepcke – Therapist

Chris Slark – Bus driver

Rajen Murugayen – Mechanic

Igor Turk – Mechanic

Alan Williams – Mechanic

Mario Pafundi – Carer

Maarten Mimpen – Carer

Klaus Liepold – Carer

Soren Kristiansen – Chef

Oli Cookson – Assistant

**

The riders sit down for dinner an hour before the staff. Chef Soren has spent the afternoon in the kitchen. No chef’s whites for him, his uniform is black with the Sky logo in large pale blue letters on the front of his apron. The Dane is calm and quietly-spoken, combining the role of chef with that of an attentive maitre d’.

As the riders come down for dinner, their starter is already waiting for them. “It’s important there’s something for them to eat immediately,” he says later. “The riders don’t come down at the same time because some might be having their message but when they come down it’s because they’re ready to eat.”

Most of the staff settle for whatever the hotel kitchen is serving up, although some cast envious glances at Soren’s tender-looking steaks and wait until the riders have finished eating before polishing off the left-overs. The hotel’s meat course is a bit of a mystery and, judging by the concerned looks around the table, I’m not the only one wondering what it is. Surely it can’t be chicken? Chicken shouldn’t be served pink.

Nicolas Portal, the team’s French sports director, asks the waitress.

“Lapin,” she says. Rabbit.

Portal’s English is still stuttering past the beginner’s stage and his mis-translation has knives and forks clattering onto plates as everyone stops, mid-chew. “Chicken,” he says, before realising his mistake.

Unlike Soren’s food, which has vanished, much of it goes back to the kitchen uneaten. You can see why some teams employ their own chef.

**

SUNDAY – Prologue, St Jean de Maurienne

It is a couple of minutes past eight in the morning when Team Sky’s bus, truck and camper van head for St Jean de Maurienne. On the way, an aggressive sky cracks and the rain is heavy for a while.

We stop for fuel and Chris Slark, the bus driver everyone calls Slarky, puts in 350 litres of diesel. It costs 504 euros. “That’s only just over half way,” he says in a gentle West Country accent. The tank holds 650 litres and Slark will be buying more fuel in a couple of days. Team Sky has two of these buses, each costing around £750,000 to purchase and customise. They are thirsty beasts and today, when parked up for eight hours with everything running while the riders wait for their start times, it will burn around six litres an hour. “Because of the distances involved, it’s difficult to be a green sport,” says Slarky, who has worked in Formula 1 and has done everything from driving the bus to changing tyres and refuelling in the pit lane.

After pipping the Quick Step bus to a stretch of pavement on one of the little back roads in the town centre, the staff quickly get to work pulling out the awning on the bus, setting up the turbo trainers and fencing off an area for the riders to warm-up in with smart Sky-branded panels.

It’s about an hour before the riders arrive. They get changed and set off to ride the course. It’s still drizzling although the forecast is for it to brighten up later. Because of the changeable weather, Sky have decided to put Geraint Thomas off first, with Boasson Hagen in the middle of the order and Wiggins their last man to tackle the 5.4-kilometre circuit.

The roads are still damp in places so when Thomas rides so he has to be cautious through the corners and over the white road markings, which can be perilous when wet. Wiggins gets into the passenger seat alongside Yates. Any clues he can gather now will help him later.

It is not a surprise that Thomas sets the fastest time when he crosses the line. It withstands David Zabriskie’s effort a minute later but later falls to Maarten Tjallingii of Rabobank. Flecha is Sky’s next rider, one of the few to ride with a radio earpiece. The Spaniard pushes down the starting ramp and swings left, then right up the narrow hill. It is a lung-busting climb that will take the fastest riders a minute or so.

Yates follows in the team car. He’s frequently on the radio, offering encouragement and information.

“That’s it Flecha. That’s good. Come on now.”

“Careful on this corner, it might still be wet.”

“Last two kilometres. Push, push, push. It’s nearly over.”

“Good work, Flecha.”

It is good work. Flecha’s time is a second quicker than Thomas.

Radio Tour, the channel that gives out race information to all the team cars, confirms that Sébastien Hinault has set the fastest time on the hill despite being one of the slowest overall. Hinault rides for the team sponsored by Ag2r, the insurance company, and its base is in Chambéry. “Christ, he gave it everything on the hill to get the king of the mountains jersey and then blew up big time,” says Yates.

Morning gives way to afternoon and drizzle stands aside for the sunshine. Wiggins completes his warm-up and gets ready to go to the start. “Brad hasn’t prepared specifically for the prologue,” says Sutton. “Of course, he wants to be up there but yesterday he did five hours. He’s training for the Tour de France, not for a five k effort.”

Wiggins has the best time when he crosses the line but only for a few minutes. Lars Boom, the Dutch rider with Rabobank, beats it and wins the stage. Then Alexandre Vinokourov nudges Wiggins down to third.

He gets back to the bus, disappears inside for a moment and comes out holding his futuristically silver Bont shoes. He hands them to Raj, the mechanic. “Can you check the cleats? The left one isn’t in the right place. And the gears were slipping a bit too.”

The time trial bikes use Shimano’s manual gears, while the road bikes are all equipped with the remarkable electronic system Di2 which has made changing gear like flipping channels on a television set. Switching back to the manual gears and their idiosyncratic ways can prove an issue. “With the gears on the TT bikes, you have to push the lever then pull it back ever-so-slightly otherwise they can slip,” says Alan.

Most of the riders have headed back to the hotel in the team cars after completing the course. Boasson Hagen has waited and plans to ride the 80 kilometres or so with Wiggins, who has gone to dope control.

While we wait, Oli Cookson gets chatting. Apropos of nothing in particular, he says: “I just wanted to say I didn’t get this job because of my dad.” His father is Brian Cookson, president of British Cycling and a board member of Tour Racing Limited, the company that owns Team Sky. “In fact, I nearly didn’t get the job because of who my dad is and how it might look.”

It’s a fair point. Last year, UK Sport and British Cycling commissioned the auditor, Deloitte, to examine the relationship between Team Sky and the national federation. Cookson previously worked as a landscape architect and urban designer in Madrid but spent some time on last year’s Tour with Sky. He fitted in well and then worked on the Vuelta a Espana, partly because he is fluent in Spanish.

The team was rocked by the death of Txema Gonzalez, one of the carers, during the race. Gonzalez was taken ill when he contracted a bacterial infection, which worsened and entered the bloodstream causing damage to his internal organs and bringing on septic shock. It was a terrible time. “I was one of the only people on the team who could speak English and Spanish,” he says. “I was translating at the hospital and then I was translating between Dave and Txema’s family. It was absolutely terrible. We were all in tears.”

Cookson’s role on the team is broad. He helps lug the riders’ mattresses from hotel to hotel.

“People joke about it, but having a good night’s sleep is one of the most important parts of recovery,” he says. “It also helps minimise the risk of allergies.”

Cyclists’ lungs are put under stress every day and can be susceptible to irritation. Breathing in dust from a hotel mattress every night can exacerbate any breathing problems. “Some hotels are fine but you go into others and you wouldn’t want to sleep there. During the Giro, the carpet was so dusty I could write the word ‘Sky’ on the floor with my finger. We seal up our mattresses and transport them with us for big races.”

Cookson also helps plan logistics and he translates for Zandio and Uran, who joined from Caisse d’Epargne during the winter and are picking up English slowly. Portal also speaks Spanish having ridden with Caisse d’Epargne, so between them they can get the message across.

**

It is a quarter to six by the time Wiggins and Boasson Hagen arrive back at the hotel. Their ride, partly done behind a team car driven by Sutton, has taken a couple of hours or so. Wiggins hands his SRM computer to Kerrison to download the data for analysis. Kerrison likes where he sees. “Brad recorded his peak power for the season during the prologue,” he says.

“Here, listen to this,” Sutton says. “Did you hear what happened in Luxembourg? The guys were showering in a railway station after the last stage – don’t ask me why they were showering in a railway station. Anyway, [Ian] Stannard comes out of the shower and his suitcase is gone. No sign of it. The other guys go out of the railway station and they find a policeman and tell him what’s happened. A hundred metres down the street they see this guy, he’s a local nutcase. He’s got the suitcase and he’s wearing a Sky jersey and shorts over his clothes and he’s got a pair of Oakleys on. He was wearing Stannard’s stuff!”

**

MONDAY – Stage one Albertvile – St Pierre de Chartreuse

Sean Yates is sitting in one of the Jaguar team cars, engine idling, clock ticking. It’s 5.27am. Cookson arrives, puts his bike on the roof and gets in. They wait another three minutes. The clock hits 5.30 just as the car park’s automatic gates open to let in a delivery truck. Yates sees his chance and drives through. Three minutes later, he gets a text. It’s Portal. “Where are you?”

Yates and Cookson drive south. The park up and ride the last 40 kilometres of the day’s stage. They want to see the final climb, a second-category hill that rises to the Alpine village that nestles between the twin peaks of the Col du Cucheron and Col du Coq.

“Hey, where were you?” Portal asks Yates when they get back. “I came down at 5.33 and no one was here?”

“We said we’d roll at 5.30, not 5.33,” says Yates with a smile.

“Oh well, I got another couple of hours’ sleep.”

**

The breakfast table is groaning with cereals and sauces, pots and jars. Soren sits waiting. When a rider arrives, he heads to the kitchen and returns with a large bowl of porridge, little pieces of chopped fruit stirred in to add an interesting flavour and texture.

He makes batches of his own juice every day. Fruit in the morning, vegetable in the evening. He places a jug on the riders’ table and then brings over a smaller beaker to the staff table, placing it down with a conspiratorial flourish, as if to say: “You shouldn’t be getting this, but…”

Soren used to work for the Danish embassy in London and he’s worked in ‘proper’ restaurants too but for the past seven years he’s catered to the specific requirements of professional cyclists, first for CSC, now with Sky.

He calls each hotel a few weeks in advance, lets them know he’s coming, places an order for ingredients. The menus are actually drawn up by the team’s nutritionist, Nigel Mitchell but, as Soren says: “It’s a compromise. Nigel knows that writing the menu in Manchester is fine when you get to the race you might have to drive 300 kilometres to the next hotel, which might be in the country, 30 kilometres from the nearest supermarket.”

Soren’s priority is to check the quality of the produce. “If something doesn’t have a date on it, I don’t use it. You can tell if the meat is good quality. If not, I buy my own.”

He has ten boxes of his own equipment and ingredients and he notices if this puts noses out of joint with the hotel’s chef. “I have to ignore it. Some hotels are great but others are like ‘What, is our food not good enough for your precious riders?’ It’s not that the food isn’t good, it’s that we want to know what’s in it. The salt, the fat, the ingredients. I’ve seen every type of hotel and I’m the only member of the team who gets to see behind the scenes. Sometimes you wish you hadn’t seen but I don’t say anything. I am a guest in their kitchen.”

Every evening meal comprises meat and fish, pasta or rice. “You have to make the food look good because people eat with their eyes first. In a Grand Tour, after three weeks of wet pasta, the riders almost feel dead inside, so a bit of colour makes a big difference. Usually I use chicken or turkey because it is low in fat but steak puts a smile on everyone’s face.”

Last night’s dinner was chicken in a curry sauce that tasted so good it’s impossible to believe there was no cream or butter in it. “Just water, spices and a little milk,” he says.

**

Team Sky’s bus ensures the riders travel to the race in first-class comfort. There are nine seats for the riders and they take up the front half of the vehicle, with the back reserved for a little office-style compartment. The seats are wide, comfortable and recline. Each rider has storage space for their laptops and a satellite dish on the roof means they can all watch their own Sky channel. No arguing over what to watch in here.

There are about 45 minutes to go until the start. The riders are in various states of readiness. Knees is in his shorts but has not yet put his jersey on. The colourful tattoo of a naked woman that dominates the upper part of his right arm is particularly striking.

The big screen at the front of the bus slides down and Yates begins to give his team talk. Portal scrolls through the visual presentation put together by Cookson, a mix of maps and profile diagrams from the organisers and photos from Google Earth and Streetview. Having ridden the climb this morning, Yates is able to give the riders more information than the photographs can provide. He explains that the final few hundred metres to the line kick up unexpectedly. “Edvald can be there at the finish. Rigo, Xabi, keep it together on the last climb. Brad, don’t don’t feel you have to go with anything, just pay attention and if the gaps open close them gradually, don’t get sucked into going after everything.”

Cookson has superimposed Sky logos on the pictures. “Have they painted Sky on the roads already?” asks one of the riders.

“No, I think that might have washed off now,” deadpans Yates.

**

Sutton stands a little way from the bus, so his cigaratte smoke does not blow near the riders. “It’s about the riders taking ownership now,” he says. “It doesn’t take a genius to work out that this is your Tour team right here. Well, most of it. There’s one or two we want to take a look at but basically this is the group we want to work together.

“One guy who really impressed me at Bayern is Christian Knees. I’d not seen him much before. He’s strong, he’s run 20th in the Tour before, and he’s big. He’s one of the few guys who can shelter Brad in the wind. Brad’s 6ft 3 and although he can get low, you want someone who can protect him on those windy stages.”

**

The stage has finished. Jurgen Van den Broeck of Belgium has won, Boasson Hagen was sixth and returns to the bus wearing the white jersey. Wiggins got tailed off slightly on the run-in and lost a handful of seconds to Cadel Evans and Vinokourov. As soon as he gets back to the bus, he puts on a long-sleeved jersey and rides his bike on the turbo trainer for a quarter of an hour.

“It’s something we’re trying out,” explains Kerrison. “When you think about it, you warm down after a prologue time trial that might be a six-minute effort or after a short track race. You’ve just ridden four hours, with an intensive burst at the finish. You’ve maybe ridden hard for half an hour, with accelerations and then you just come to a halt and get on the bus. It doesn’t make sense.”

**

TUESDAY – Stage 2, Voiron - Lyon

The rain is heavy in Voiron. We shelter in the team cars and watch as the riders make their way to the start line before edging out behind them. We’re barely out of the neutralised zone before a gendarme pulls alongside Yates and gestures to put his seat belt on.

With Wiggins lying fourth overall, we’re fourth in the convoy, close enough to see the back of the bunch. As they climb the hillside, we see that three riders have got a little gap. Jurgen Van de Walle, of Omega Pharma, Tjallingi of Rabobank and Brice Feillu of Leopard are in for a long and ultimately fruitless afternoon.

“I can’t work out why they’re bothering,” says Yates. “Okay, Feillu’s riding for a Tour place but Omega and Rabo have won stages already.”A text message arrives. Gossip from David Millar’s book launch in London the previous evening. I read it out. “Cavendish is joining Sky, according to the grapevine.” Silence. Then Yates says: “That’s the gossip is it?” I turn to look at him. He looks straight ahead. The effort not to give anything away is perhaps showing.

We’re not in for a rivetting day. The break is established early, the gap goes out to a few minutes and the bunch settles in for a wet trudge towards Lyon. Talk turns to how the role of the directeur sportif has changed. We talk of Cyrille Guimard, who on hot days would drive the team car barefooted wearing only a tiny pair of shorts. “When I was racing for Peugeot in the Midi Libre, Jean-Pierre Danguillaume, who was one of the directors, stopped the car, took a bike off the roof and rode up into the bunch to talk to one of his riders,” says Yates. He laughs. “The commissaire was going mad. They don’t like that kind of thing.”

Fifty kilometres pass. The sandwiches (ham, cheese and cornichons) have been eaten. Yates gets on the radio to Portal, who is driving the second team car, which is perhaps a kilometre behind him in the convoy. “Nico…”

“Yes.”

“How’s it going?”

“All in my car are sleeping. The doc is sleeping.”

We hear the doc, Richard Freeman. “Just resting my eyes.”

Knees and Gerrans drop back for fresh rain jackets and bottles.

And then we come over the brow of the hill. Yates sees the brake lights too late. The road is slippery. He stamps on the brakes. The wheels fight desperately to grip but it’s inevitable. We hit the Omega Pharma car.

“Shit,” he says. “No crashes in 12 years, then two in a month. I ran up the back of someone in the Giro.”

Marc Sergeant and his colleague get out of the Omega Pharma car. “Are you alright,” asks Yates. Sergeant inspects the bumper theatrically then wags his finger playfully, before holding his neck in mock agony.

Maybe a minute goes by. The radio sparks into life.

“Sean?” It’s Nico.

“Yes.”

“Did you have a little push? News travels very fast.”

Over the next hour, a couple of other team cars pass. Lorenzo Lapage of Astana passes and peers at Yates then shakes his head. The pair worked together at Discovery Channel. “I’ll get a reputation,” says Yates before pointing out the man in the back seat, one of Astana’s soigneurs.

“That guy used to box for the Soviet navy. Imagine how hard he must’ve been.”

**

Just like the car crash when a momentary lapse of concentration caused an incident, so the least eventful days can suddenly turn on their head.

There are just 22 kilometres to go when we pass through the village of Chavaille. A couple of Quick Step riders are on the floor and Yates picks his way past them and threads the Jaguar through the narrow, winding roads. The television on the dashboard has kept cutting out but we see Sky’s riders driving the pace. “Are we on the front?” asks Yates. Soon we realise that the bunch has split and that a group has got away. Vinokourov is in it, Sky are chasing.

Yates wants to get up to the group containing the Sky riders but we’re stuck behind the third group. The road narrows and then there’s a central reservation. We pass Boasson Hagen, who hit a pothole on a fast descent, puncturing his front tyre and shattering his rear wheel. Uran gave him his front wheel but the Norwegian had to wait for the neutral service bike to replace the rear. Yates passes him, there’s no way back now.

Wiggins is on the front now doing a big turn before settling in behind his team-mates who close the gap. At the finish, Wiggins is alert and racing. There’s a split. By the time the next group has crossed the line, Wiggins has gained six seconds on Evans. A small advantage but an encouraging sign to Sutton. “He’s taking responsibility. You see that gap, it was hardly anything but the time isn’t taken between the back of one group and the front of the next. So a small gap on the road can me five, six, 10 seconds gained or lost.”

**

Dinner is nearly done. It’s 10.30 but some staff still haven’t appeared for dinner. “Where are the carers?” asks Sutton. “Where’s Klaus?” Klaus is still at the massage table, working on Geraint Thomas.

After the finish, the riders’ recovery drinks were not ready and waiting in their seats on the bus as they should have been. A small but vital detail had been overlooked.

Sutton gathers the staff around him. “Listen guys, we’re a team, but Klaus is still up there working. Today we had a problem with the recovery drinks. They have to be there for the riders. I don’t care who was supposed to do it but work it out between you, okay? Take responsibility. If you’ve finished your work don’t just fold your arms, see if there’s something else you can do. If you see a bloke who’s struggling and you’re all done, ask him if you can help. The riders are really pulling together and I want to see everyone do the same. Don’t let your mate fail.”

**

A little later, Sutton and Kerrison are talking about the Tour team, how it should be selected and when it should be announced.

“What are we going to do?” asks Sutton. “Ring every rider that’s not in it first so their feelings aren’t hurt? We’re picking a team to do a job. You tell the guys who are in it first. If you don’t get a call, you’re not in it, surely?’

Kerrison doesn’t quite agree with Sutton’s old school approach. “The riders we’re not selecting are still part of the organisation.”

“I’m surprised Simon hasn’t asked yet,” says Sutton. “He usually wants to know what’s going on.”

**

WEDNESDAY – Stage 3, Grenoble time trial

It’s raining again, so Flecha is the only rider who opts to ride round the time trial course in the morning. He heads out with Sutton. The others take a trip round in the cars.

This course will be used again at the end of the Tour de France. It’s 42.5 kilometres and it climbs almost from the start. The profile provided by ASO makes the first hill look easier than the second but, in fact, everyone agrees it’s the other way round.

Out on the course, HTC’s Tony Martin is paying particular attention to the flat section at Saint-Martin-d’Uriage and the technical, cobbled left-hand turn. I watch him ride that stretch a couple of times.

Later, I take a taxi to the start. “I’ll jump in with you,” says Sutton. On the way, we discuss Wiggins’s chances. “It’s a good course for Brad. It isn’t really technical.” I mention Martin’s detailed reconnaisance. “He’s here for the stage, isn’t he? He lost a load of time the other day so he’ll go all out to win today. We’re not worried about the stage. I think Brad will be top three but we’re here for GC. The whole goal is to do as well as we can on GC. Brad knows that. But this time trial in the Tour will be very important. Brad could take minutes from some of the climbers. If he’s 12th he could move up to ninth. If he’s ninth he could move up to sixth.”

Talk turns to the continual evolution of Team Sky. “We need more guts in the team, you know? Guys like Mat Hayman have got guts. The team will look a lot different next year. We need more climbers and we’ll have a couple.”

Who are they?

“One guy you’ll never guess. He’s not even a pro yet.”

Is he Colombian?

“How d’you know that?”

There aren’t many places you can find untapped, unsigned talent, and there have been rumours since the spring that Sergio Henao, who won the Vuelta a Colombia last year, has agreed to join Sky after Uran vouched for him.

**

The clock over the finishing line counts down. Wiggins is not going to beat Tony Martin’s time. At the second checkpoint, before the long descent and run-in to Grenoble, Wiggins was level on time with the German. But then it began to rain and he conceded 11 seconds.

He thumps the gear levers on his tri-bars in frustration. He may not have won the stage, but Wiggins has taken the yellow jersey.

There’s no sign of either of the carers, Maarten or Mario. Has there been another oversight? The UCI’s chaperone is here to escort Wiggins to the dope control but Wiggins is irritated to be without a helper.

“Where’s my soigneur?” he asks.

I ring Sutton. “There’s no carer here for Brad.”

“He said he was coming back to the bus, no matter what.”

Back at the bus, the chaperone has caught up with Wiggins and takes him, together with the doc, to give a sample.

“He’s just had a go at me in there,” Sutton tells Yates. “He said ‘Where were my time gaps to Tony Martin?’ and I said ‘You can cut that bullshit for a start.’ We told him he was level at the last time check, what more does he want? There weren’t any more time checks to give him.

“He got to the time check level with Martin and then he gets to the finish and he’s frustrated he hasn’t won the stage, which is understandable, but this wasn’t about the stage win. It was raining on the descent and the most important thing was that we took no risks.

“On the descent, he made this gesture to us with his hand. I thought he was saying he had a flat tyre but what he meant was ‘Talk to me.’ He wanted to know the time to Martin but we didn’t have any more time checks.”

As for the absence of a carer at the finish line. “He said he didn’t want one. Then he wonders why there isn’t one.”

“There’s never a dull moment with Brad,” says Yates. “You’re either laughing your head off or tearing your hair out. Or both at the same time.”

Sky’s bus is the last one in this back street. Most of the spectators who had waited for Wiggins have given up. It’s well past 6pm.

Wiggins arrives, the yellow jersey on his back, a Crédit Lyonnais lion under his arm. “Payback for Albi,” he says, a reference to the 2007 Tour when Wiggins finished fifth in the time trial won by Vinokourov just a few days before the Astana rider tested positive for a banned blood transfusion.

**

The atmosphere at dinner is bright and light. There are smiles and laughter at the riders’ table.

After he’s finished eating, Flecha sees an opportunity to wind up Slarky. Time trials pose a logistical challenge and it isn’t possible for every rider to be followed by Yates or Portal. So Slarky drove a team car behind the Spaniard. With his experience changing Formula One car tyres, Flecha would be in good hands.

“Hey, Slarky, you know I got a fine today? One hundred Swiss Francs.”

It transpires that midway through the ride, Slark pulled level with Flecha and offered him a bottle, which is strictly prohibited in time trial stages.

“Yeah, the commissaire was going to penalise me two minutes as well.”

Slarky’s face drops until he realises he’s having his leg pulled by Flecha, who seems to be in permanent possession of a smile.

Alan Williams, one of the mechanic, says there was a near miss with Knees too. “Bob [the physio] was waiting to jump into a neutral service car with a pair of wheels for Christian but ASO said there wasn’t one free,” he says. “So I grabbed the wheels and gave them to the guys at Movistar, who were going out behind Christian. If he punctured, he’d only have to wait a minute to get a wheel. Yeah, it’s a lost minute but it’s a lot better than DNF-ing.”

**

THURSDAY – Stage four, La Motte Servolex – Mâcon

With the yellow jersey to defend, Sky are in for a challenging day. There’s more than the usual attention around the team’s bus in the morning but this is nothing compared to the Tour. The atmosphere is relaxed, the sun is shining and music is blaring out of the bus. Even though it’s not to his taste, and he agrees it sounds like a bad holiday in Benidorm, to the doc, this is a good sign.

“It means they’re up for it,” he says. “I have to say, some of the lyrics are a bit much. During the Tour, Dave had to ask them to tone it down a bit.”

Yates, who currently has an Eagles CD on a loop in his team car, steps out of the bus and leaves them to it.

I get into the car with Maarten and Mario, the two carers who are heading to the feed zone. They are like chalk and cheese. A laidback Dutchman and a hyper-active Italian and the journey is enlivened by their double act.

The feed zone is on a long, straight road, as they often are. Maarten picks a spot and pulls over.

About an hour before the riders are due, Maarten hangs eight musettes on the car’s tailgate and begins to load them. Three energy gels, two bars, a small rice cake wrapped in foil, a bidon, a little can of coke. Mario goes off to talk to his friends at Liquigas.

“You wanna be careful,” Maarten tells Mario when he comes back. “It looks bad for you. I do all the driving, then I do all the work while you go and chat. You’ll be sleeping next.”

“No, no, don’t write that,” says Mario, before launching into the best Shane Sutton impression I’ve ever heard from an Italian, although in truth it sounds more like the drawling Marlon Brando in the Godfather. I mention this and Maarten says: “Mario is from the south of Italy, Salerno. He’s almost Mafia.”

Mario used to race. He was a promising under-23 with the amateur Vellutex team at the same time as Yaroslav Popovych but says he became depressed and gave up racing. He begins to talk about his depression but his English is not quite good enough to explain the nuances and it leaves him frustrated.

The bunch passes through and the bags are grabbed without incident. Wiggins and Boasson Hagen do not take the risk of trying to take their bags, so Mario passes them to the team car. One of the riders will drop back for them later.

**

We’re in the bus, watching the race on the pull-down screen. Sutton is playing a cricket game on his iPhone. “I’m trying to beat New Zealand.”

He seems able to concentrate on two things at once. “The finish is a bit like a mini version of Bordeaux, isn’t it? You come into the town, over the bridge, right-hander, then quite wide roads.”

We watch as Team Sky set up Boasson Hagen for the finish. Thomas puts in a big effort to open the gap for the Norwegian but he just mistimes his effort and is pipped into second place by John Degenkolb, the HTC rider who won two days ago in Lyon.

“Shit,” says Boasson Hagen when he gets back to the bus, but there are no recriminations.

“Thanks man,” he says to Thomas when he arrives.

“No problem. Happy to do it.”

The riders head off to the hotel by bike but Nicolas Portal’s Jaguar is not going anywhere. The automatic gearbox is faulty. “It’s only using two gears and it won’t go more than 90 kilometres an hour,” explains Alan, who laughs when I suggest he should get under the bonnet. “I’ll stick to bikes.” At the Tour, Sky have a Jaguar mechanic with them in case the cars go wrong. “I’ve rung Jaguar,” says Alan. “But it’s not going to be fixed before the weekend.”

**

The Hotel L’Escatel in Mâcon is not the best. If you arrived here on holiday you’d probably consider sleeping in the car. There’s a mangy looking cat curled up on a chair in reception. It wakes up and hops down onto the floor and walks, with a slight limp, into the dining room.

There is a wonky table tennis table pushed up against the wall and an old babyfoot table. The little wooden footballers are chipped and jaded. The idea of lugging eight mattresses for the riders begins to make more sense.

Fortunately, I don’t have to. Because the hotel is full, with Garmin and Saur-Sojasun also staying, a couple of us are down the road in another hotel. It’s no better, although Garmin’s Dan Martin refuses to believe it’s any worse than the L’Escatel, when I bump into him.

On the other side of reception is one of those novelty massage chairs where you insert a euro and the thing wobbles about for five minutes curing aches and pains.

“You could save a fortune on soigneurs,” I say to Tim Kerrison.

“Have you used one of those chairs? They’re actually pretty good. Maybe we should get them on the bus!”

Wiggins is the last rider to arrive, having been delayed by the podium presentations, press conference and dope control, the holy trinity of responsibilities that mark you out as an achiever.

We walk across to the hotel and Wiggins explains that he’s feeling confident about tomorrow’s finish at Les Gets. “It’s not that hard,” he says. “Saturday is the big day, but the team is so strong I think we will be alright.”

In reception a couple of journalists from a French newspaper are waiting for him.

**

FRIDAY – Stage five, Parc des Oiseaux – Les Gets

Last night, Wiggins lit up Twitter. “Anyone fancy working as a press officer for me out here? Getting pulled left and right, need help?”

The response is predictable. Dozens of people, from PR specialists to eager fans volunteer to get on the next flight. A few say they relish the opportunity to “crack a few journos’ heads.”

Earlier in the day, Sutton had said that if he had his way, he’d ban the riders and staff using Twitter. “You make a negative story if you ban it so it’s not worth it. But last year a few things got said that weren’t the image we wanted to project. We’ve told the riders, you’ve gotta be careful.”

The Dauphiné is hardly a pressure cooker and it doesn’t bode well for the Tour if he is struggling to cope with a handful of approaches a day but he says he was only joking. “This was supposed to be a dry run for the Tour in every respect but the press officer couldn’t come here because he’s on holiday,” he says with a roll of the eyes.

Sutton knows that the media is Wiggins’s Achilles heel. “It’s something you have to cope with at the Tour. Everyone wants you if you’re doing well. I remember at the Worlds when Nicole Cooke won the junior road race and she reacted a bit strongly when there was one camera in her face and I pushed a guy away to give her a bit of space. The next day I saw Jan Ullrich and he was absolutely surrounded. There were hundreds of them and he could hardly move but it was like he didn’t see them. He just blocked them out.”

**

Dave Brailsford arrived last night and after the race rolls out from the start, he travels on the bus to the finish at Les Gets. On the way, he makes and receives a dozen or more calls as the bus becomes his office, discusses the cost and timetable of some crucial repairs the buses will need later in the year, and then outlines his vision for a more appealing, televisual and investment-friendly sport.

As we drive through the péage, one of the toll booths on the autoroute, the Katusha team bus veers across in front of us. Clearly the driver hasn’t seen us and Slarky has to drive into the layby to avoid a coming together.

“That’s payback for Swifty, that was,” says Brailsford, referring to the signing of Ben Swift when he was under contract with the Russian team. “Actually, no, payback will be worse than that.”

**

The team hotel in Les Gets is an attractive, if stereotypical mountain chalet. The mechanics and some of the other staff have already arrived and are tucking into pizza and beer. This is a rare afternoon when the punishing and repetitive schedule eases slightly. A hotel two minutes from the finish line offers the chance to get a proper lunch and get on with the work.

Wiggins defends the yellow jersey comfortably. The French rider Christophe Kern takes the stage and Wiggins is alert and composed in his yellow jersey.

He arrives back at the hotel to find his turbo trainer and bike have already been set up in the little wooden porch of the hotel.

The hotel owner’s ageing labrador dozes next to the bike. Someone has balanced a Sky baseball cap on the dog’s head but he doesn’t seem to mind. He only opens an eye when Wiggins gets on the bike and the turbo whirrs.

Sky’s terrier-bulldog cross, Sutton, is by Wiggins’s side as he warms down.

“That was great today,” he says.

“I felt shit at the start. It was full on at the start, like the old days, but on the climbs no one is doing anything ridiculous. They’re attacking but then they just stay there,” says Wiggins.

“That’s what’ll happen. They’ll get 30 metres and that’ll be it so there’s no need to panic,” says Sutton. “Even when G was on the front, they weren’t getting anywhere. The package is there, just stay calm mate. Even if you feel you’re coming down a bit, don’t worry because they’re getting tired too.”

Gerrans, as chirpy as ever, walks through reception. “The first 100k were ridiculous. It was like a criterium with attacks going left and right. We couldn’t control it, no one could. If too big a group went, we shut it down. The problem was, it was on big roads so it was really hard for a break to get away. On smaller roads you can control more because you can brake through a corner and let the gap open. But when it’s big roads everyone’s trying to go across, the group gets too big, so you shut it down. Then the attacks start all over again. A hundred kilometres for one guy to get away?” He shakes his head. “Pfft.” The lone escapee was Jason McCartney of Radioshack.

**

In the evening, Carsten Jeppesen, the team’s head of operations arrives. Perhaps it is the configuration of tables in the restaurant’s little dining room but from this point on there seems to be more of a subtle split between the management and the staff. Whereas earlier in the week management and staff ate at one big table, now there appears to be more of a hierarchy. Brailsford, Sutton, Jeppesen, Kerrison and the doc are at one table; everyone else is at another.

Yates does not appear for dinner. He popped down earlier, saw no one was there, didn’t particularly fancy raclette for dinner and went back to bed. Considering he is usually up at dawn to go for a ride and is training hard for the upcoming national 50-mile time trial, it seems unthinkable to miss a meal after a hard day behind the wheel.

**

After his dinner, Wiggins sits down to talk. He explains the difference between last year’s faltering season and his current demeanour, which seems a world away.

“I wasn’t leading the team in any sense and I was becoming quite withdrawn,” he says. “I felt I needed to change and I let people start to help me a bit more. I feel confident to lead this team now, confident to tell people what to do. Last year I just couldn’t. It had been such a drastic change. I went from going to the Tour to help Christian [Vande Velde] to finishing fourth. I don’t think I understood what a change that was going to be. I was the underdog and if I’d cracked in the last week and finished ninth, no one would have said anything. I made a few cock-ups last year, media-wise too.

“When I came to Sky, Rod Ellingworth was designated to coach me. I just said ‘Yeah, okay.’ But I didn’t have faith in Rod’s coaching. It wasn’t anything to do with him but I didn’t know him and he didn’t know me. I don’t think he had that rapport with me. I was very good at telling him what he wanted to hear and convincing him of what I needed to do.”

So, Wiggins was steering things rather than the coaches?

“I think so, yeah, and I take full responsibility.

“Shane never lets me cut corners or shy away. He just cuts the bullshit out. Last year I didn’t ride the Nationals because I didn’t feel I wanted to get out there and race a week before the Tour. Instead, I went and tested on my local climb in Girona and set a record up it so I thought I had the form. But I had nothing to back it up.”

**

SATURDAY – Stage 6 Les Gets – Le Collet d’Allevard

The doc is in the hotel’s bar, laptop open, phone pressed to his ear, looking concerned.

Rigoberto Uran has been suffering with breathing difficulties for the past couple of days and Dr Freeman is trying to get a Therapeutic Use Exemption for a drug to treat him.

“It can be very tricky, especially at the weekends,” he says. Yesterday, Dr Freeman contacted the race’s anti-doping doctor and put the case for a TUE. The drug is a steroid that can mimic a corticosteroid in the urine and can be misused.

“Rigo has got a chest problem,” he says. “With most asthma patients, you will never find out specifically what causes it. We’ve tested for pollen and in Rigo’s case it doesn’t appear to be that.

“The ADAMS [World Anti-Doping Agency’s Administration and Management System] website can be tricky. Your worst fear is that you’re stuck in the mountains with no internet connection but we would not give anything that’s on the list to a rider until we had everything confirmed through the proper channels.”

Could he not use the ADAMS hotline and make a phone call? “That works well Monday to Friday but not so well at the weekends,” he says wryly, acknowledging that the onus is always on the athlete and the team doctor to ensure everything is done properly.

It took a few tries but eventually, he got through to Dr Mario Zorzoli of the UCI and gained the necessary permission.

But isn’t there an argument that if Uran is unwell and his breathing is seriously affected, he should pull out of the race? “He may well do that. But he’s an ambitious young man who wants to support Bradley and he wants to secure his Tour team.

“We are not talking about performance-enhancement here. The TUE is designed to enable an athlete to take medication that a normal human being would be prescribed by a doctor. It cannot be right that you and I could go to a doctor and be prescribed something that an athlete with the same condition could not use.”

Dr Freeman used to work for Bolton Wanderers Football Club before joining Sky. He’s also worked on golf’s European Tour. Despite the challenges of being away from home for so much of the year, he enjoys the role.

I ask what he makes of the UCI’s new no-needles policy. “I think it’s fantastic,” he says. “It takes away a large window of opportunity for a lot of products. It means that there are no short cuts to proper rest and recovery. And it also removes that ladder of progression. If riders get used to vitamin injections as a matter of routine, it makes it easier to not question what’s in the syringe.”

**

This is the crucial day of the Criterium du Dauphiné. If Team Sky can defend Wiggins’s yellow jersey over the Col des Aravis, the Col de Tamié, the Col du Grand Cucheron and on the hors-categorie Collet d’Allevard, he will clinch the biggest road race win of his career.

Yates delivers his team talk in his usual sparse fashion. The riders are not overloaded with information. “There’s a lot of guys in the hurt box. I watched the highlights yesterday and Bradley was riding fantastic and doing things super coolly and clever, which bodes well. I think you can see that Bradley is in super form and that is great for our confidence.”

He talks them through the stage, warns them of the dangerous descent on the Aravis. “The break should go on the first climb. Yesterday it took a long time to go so if we are a bit on the edge, it’s not the end of the world if seven or eight go.”

“I think we need to take advantage of the villages,” says Gerrans. “If you could tell us when the villages are coming up, we can let a group go just before and then let it go away as you go through a few corners.”

Yates finishes his talk reminding the riders to pay attention to their eating and drinking. “When it’s up and down all day it’s easy to forget so just make sure you are keeping fuelled. And more importantly, make sure Bradley has everything he needs because if he runs out, we’re all fucked.”

He hands over to Brailsford.

“All I’d say is I thought you rode f***ing great yesterday guys. You deserve a huge pat on the back,” he says. “At the finish yesterday, Johan Bruyneel came to find me, and I get on well with Johan, and basically he said: “You know what, your guys, your team there were f***ing brilliant. You were super strong and everyone’s saying it.” I think you should take a lot of pride and confidence from that. When one of the best guys in the world at what he does says that, you should take a big pat on the back. Now you can raise your game, you’ve got something to ride for, you’ve got purpose.”

**

Driving up the Collet d’Allevard is a shock. The climb is much harder than even the race manual led you to believe. There is barely any respite.

Brailsford gets into the bus with Jeppesen. “That is a very hard climb. Harder than Alpe d’Huez, I’d say.”

There’s a crash on the descent of the Grand Cucheron when a couple of cows wander into the road.

The race reaches the bottom of the Collet d’Allevard and Vinokourov’s Astana team come to the front.

“He looks good, eh?” says Jeppesen, referring to Wiggins, who is in the perfect position.

“Let’s see how he is at the top,” says Brailsford. “I think Brajkovic could be good today. We need to be wary of him.”

With 8.5 kilometres to go, Brajkovic is dropped. “You see, this is why I am sitting here in the bus rather than down there in the car!”

Boasson Hagen puts in an astonishing turn and shreds the lead group. When Joaquin Rodriguez attacks, Wiggins rides sensibly. He uses other riders to help him close gaps and he refuses to get sucked into matching those who are more comfortable with the frequent changes of pace.

At the summit, he hasn’t just kept his yellow jersey, he’s extended his lead over Cadel Evans to 1-26.

**

The race has come full circle. We’re back at the Best Western in Chambéry, where the week began, except this time there’s a wedding taking place. How the bride and groom feel about sharing the hotel with a cycling team is anyone’s guess.

Jeppesen drives Wiggins and Sutton back in his unmarked Jaguar, the only one that isn’t plastered in Sky logos. Wiggins takes a phone call and talks quietly. I just about hear him say:

“Yeah, it was good… Bloody hard, though. Bloody hard.”

Wiggins arrives back at 7.40pm. Because of the late finish, the nightly text message from Nicolas Portal makes grim reading for any of the staff with a rumbling stomach. Dinner isn’t until 9.45. Portal sends a text every night listing the evening’s dinner time, what time the riders have to wake up and have breakfast the following morning, when their suitcases must be in reception and when they leave for the start. It also details the dress code, which alternates between white shirts and black.

Tonight is a white night and Thomas is wearing black. Brailsford calls over to the table and says: “We’ll take this into account when it comes to contract negotiations, G.”

**

SUNDAY – Stage seven, Pontcharra to La Toussuire

Brailsford and Sutton are in the hotel foyer at 7.30, drinking a black coffee and ready to ride. Jeppesen has left his cycling shoes in a team car and has to wake one of the mechanics to get them out.

We’re going for a ride all the way around the lake at Aix-les-Bains. It starts off civilized enough. The sun is up early and glints off the lake but as we begin to climb, Jeppesen and I are in trouble. Sutton drops back and offers some stern words of encouragement. When we get over the top he asks how much riding I’m doing. I answer honestly but get the feeling he doesn’t believe me. I need to lose a bit of weight to cope with hills, I say.

“Losing weight is an endurance event, mate. I say to anyone who wants to lose weight – it’s simple. Prepare to feel f***ing hungry.”

Once the climbing is over, it’s a flat-out run back to Chambéry on rolling roads. Sutton, who is 53, rides at the front the whole way. “The bulk of my riding the last ten years has been like this,” says Brailsford. “No breakfast, just a black coffee, and an hour and a half or two hours sat starting at his backside.”

Back at the hotel, Jeppesen looks like I feel. His face is red and his accountant’s haircuit unusually ruffled. “That little smoking f***er,” he says. “Twenty five kilometres he rode on the front and no one gave him a turn.”

**

At the start, despite a two-and-a-half hour ride, there’s a spring in Sutton’s step as he bounds back to the bus with a pile of pizza boxes under his arm. “The boss must be knackered. He wants pizza.” Some of the staff tuck in under the shade of a tree.

Brailsford has an easy manner about him this morning. He asks how the week has been and I reply that it’s been illuminating.

“There’s nothing going on here,” he says, answering a question that hasn’t really been asked.

“Absolutely nothing at all. I know that’s not good enough for some people. It’s like the no-needles policy. I think that is absolutely great but how’s it being enforced? I’ve spoken to Pat [McQuaid, UCI president] and I told him the UCI needs to get out here and enforce it. Where are they? They need to be on the buses. There are 20 teams, how hard can it be to have an observer on each bus? That’s your window of opportunity for recovery there, between the finish and the hotel, so get someone on the buses.

“The doctors are scared, you know. Okay, so if you give someone something to go uphill faster, that’s one thing. But very few people are prepared to risk going to prison to make someone go uphill faster.”

**

I’m in the second team car with Nicolas Portal. We’ve barely got underway when a break of 11 gets clear. In it are Andrey Zeits of Astana and Alexandr Kolobnev of Katusha. Team-mates of Vinokourov, who is a potential threat, and Rodriguez, who although three minutes down, might try a long attack from the Col du Glandon.

Yates is on the radio asking the Sky riders to let the gap go out to about five minutes “just in case Katusha are thinking of getting Rodriguez away so he can bridge across to Kolobnev”.

A few kilometres later, Yates is on the radio again. “McGee [Bradley, the Saxo Bank sports director] has come alongside me and said they don’t want it more than five minutes because they want the stage for Chris Sorensen. So let the gap go a bit more and they’ll ride.”

Tactically, the stage begins perfectly. Sky are in control. Early on the climb of the Glandon, which turns to reach its summit on the Col de la Croix de Fer, riders are in trouble. We see three Movistar riders call it a day and turn round in the road to descend against the direction of the race.

But by the summit, Wiggins has just Uran for support, and he is hanging on. Boasson Hagen has been dropped.

We’re back with Flecha and Thomas and will follow them all the way in, even though they are destined to finish outside the time limit, while listening to Yates’s updates on the radio.

The doc tells a story about yesterday’s stage. “Flecha and Xabi were riding up and a group of Spanish fans clearly said something because Flecha stopped pedalling and gave them a bit back. I asked Flecha what they’d said and it was: ‘Look at these fat arses’.”

Over the top of the Glandon, Yates’s tone is reassuring. His voice is never raised, it’s just the same languid register. “Perfect, perfect. Remember, we’ve got Kanstantsin if we need him,” which suggests some sort of agreement has been made with the HTC rider, Siutsou.

**

Even before Wiggins had won the Dauphiné, some journalists and armchair experts were predicting that he had come too good, too soon. The assumption is that a good Dauphiné usually leads to a bad Tour.

But Kerrison is adamant they’ve got their planning right. “I am 100 per cent convinced there’s more to come at the Tour.”

He talks through some of Wiggins’s numbers. “The first 30 minutes of the Collet d’Allevard, his power was 430 watts, average. That tailed off to 408 for the last seven minutes. His cadence also tailed off a bit. The first 15 minutes of the Grenoble time trial, going uphill, he was doing 480 watts.

“There were two reasons I was nervous about riding the Dauphiné for GC. Firstly, if he had to go super deep to defend the jersey. But the first five days were not at all stressful. The last two were hard but today is short. I’m not worried. We didn’t want to put him into a hole we couldn’t get him out of in time for the Tour but we haven’t done that. Secondly, it will increase expectations. Last year he had all that expectation and he didn’t perform well. This year, he’s been under the radar and he’s done well.

“But the Dauphiné has been carefully planned. Winning it is fantastic – or would be fantastic,” he says, careful not to get ahead of himself. “If it had been planned as a peak, then sure, it might have been difficult to get back up for the Tour but it wasn’t. He didn’t back off after Bayern and taper. He raced well at Bayern, then had a good week of training. He came here already fatigued. He’s not come into this race fresh, so it’s been good to see what he can do in a race on the back of a block of work. After this we’ll do four more days at altitude in Sestriere and then taper for the Tour.”

In May, Wiggins and a few other riders spent time in Tenerife, training at altitude. “It’s the best, most productive thing I’ve ever done,” he says. “Last year I suffered when the Tour went high and it goes higher again this year. I basically lost 100 watts every time it went over 1,500 metres. After ten days in Tenerife I had that 100 watts back. It’s not just about being at altitude, it’s about training to perform at altitude.”

As Kerrison says: “People underestimate the impact of being at altitude.”

**

Yates is on the radio. We’ve still got seven kilometres to go, following the riders who are outside the time limit but up ahead, the race is won.

“Nico… On a gagner.” There is barely a hint of elation in Yates’s voice.

“Have you opened the Champagne?” asks Portal.

“Red Bull for me.”

We pass a group of British supporters, from Yorkshire judging by the accent.

“‘As he done it?” they ask.

Portal doesn’t understand at first, so the doc explains.

“‘As he done it,’ they asked. So you reply. ‘Yes, ee ‘as done it.”

“Yes, eee has done it,” says Portal in the closest you’ll get to a Frenchman doing a Yorkshire accent.

“That concludes today’s English lesson,” says the doc, who is now on great form. As we draw alongside Thomas, he hands him a bottle and says: “Beautiful scenery, isn’t it G?”

Thomas looks to his right at what is, admittedly a stunning view, although with sweat pouring from his brow and his jersey zipped to the waist he’s probably not in the perfect frame of mind to enjoy it. “Yeah. Lovely!”

**

There’s an end-of-term feeling at the top of La Toussuire. Everyone is packing up to go their separate ways. The riders will head to Sestriere and will celebrate Wiggins’s win with a pizza and a glass of wine. Raj and Alan, the mechanics, will drive back to the team’s service course in Mechelen, near Brussels. The satnav tells them they can be there by 3am if they don’t stop for long. Raj will set off again tomorrow, to drive to the south west of France for the Route du Sud. Yates will drive his Jaguar all the way home to southern England. Probably without stopping.

It all seems very low-key, considering this is the biggest win Team Sky has enjoyed so far.

But that’s life on the road. Once the job is done, another one is there to be started.

For Alan the mechanic. That means a week prepping the Tour bikes. As we descend La Toussuire in one of the Mercedes vans a thought suddenly strikes him.

“I didn’t even get to say well done to Brad.”

**

Wiggins is a mass of contradictions. He can say one thing to the press one day, and something else the next. It’s difficult to know what he really thinks.

During the race, he told French television that the Tour couldn’t have been further from his mind and that he was concentrating simply on the Dauphiné. A few days later, he tells me that the Dauphiné was just part of the plan for the Tour. When I point out the apparent conflict in the two statements he explains that it’s possible to live in the moment while working towards a longer-term goal.

But there was no feeling of relief or joy after the Dauphiné. “It still hasn’t really hit me,” he says. “I don’t know what I’m supposed to feel from it really. It was about going there and racing hard and building form into July.

“I knew I was in great shape but I never felt like I was in great form. I was actually quite tired off the back of six weeks of hard work. I’m still in the middle of it, I’m going to a training camp rather than going home to have people tell me how great it was.

“I’ve always raced fresh but this was about building the conditioning to cope with the demands of a three-week race. Last year I went to the Giro and won the prologue but I had no depth. This year I’ve had five days off since Roubaix. At the Tour of Romandy I was 70th in the prologue and everyone’s asking what went wrong but I’d done five hours each of the two days before. It is hard to explain to people and they just think you’re making excuses.

“People will say I’ve peaked too soon but imagine this, if I’d been a minute slower in the time trial, or if I’d sat up one day and lost a bit of time, and then raced the last three days exactly as I did – following the wheels – people would have said: ‘Oh he’s well on track for the Tour, there’s more to come. You can’t win really. I know where I’m at.

“I think the whole team shone. Christian is like an old school Sean Yates. He does things instinctively without being asked. I thought ‘I could do with a bottle’ he’d turn up with ten up his jersey. Edvald’s climbing was brilliant, G did a lot of work. I think as a team, that’s the best we’ve ever ridden, and it’s taken 18 months to get to that point.”

Critérium du Dauphiné final top five

1 Bradley Wiggins (GB) Sky 26-40-51

2 Cadel Evans (Aus) BMC at 1-26

3 Alexandre Vinokourov (Kaz) Astana at 1-49

4 Jurgen Van den Broeck (Bel) Omega Pharma-Lotto at 2-10

5 Joaquim Rodriguez (Spa) Katusha at 2-51

This article first appeared in Cycle Sport August 2011

Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/cyclesportmag

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.