'I spent 40 days and 40 nights in isolation, then went on to claim medals' - cycling is a daily motivation for Transplant Games athlete

Topley spent six weeks in isolation after a bone marrow transplant, but returned to become a medal-winning racer

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When I catch up with Nicholas Topley in early 2024, he has just returned from a ride. Barry Island in South Wales (UK) is the venue, and the wind has been blowing hard as usual. “The wind direction is either one way or the other,” he says. “Today it was from the east, which is not usually as bad as from the west.” He’s been trying out some new Flandrian socks, which he’s happy to report have prevented frozen toes despite the minus-four-degree winter windchill.

Battling chilly, windy training rides is a familiar scenario up and down the country – but 63-year-old Topley’s story is anything but run-of-the-mill. He is a survivor of aplastic anaemia, a bone marrow transplantee, and a regular competitor at the Transplant Games – from which he has brought back a host of medals since he began competing in 2019.

Topley wasn’t even a cyclist in 2004, at the start of what turned out to be a very long, very arduous journey. He was first diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis, which, of all the things that were still to come, Topley describes as the worst. “It was probably the only time I really ever thought about the fact that I might die because I was so ill. It was just awful,” he says.

Following treatment he went into remission for a number of years. Ironically, it was only as he was being officially discharged from the liver clinic that Topley – who worked in senior leadership at Cardiff ’s Heath Hospital, where he had also been treated – glanced at his notes and realised that something was still very wrong. His haemoglobin count was around half of what it should have been. “That was the beginning of my bone marrow failure,” he says. “Within three months, I was requiring blood transfusions because my bone marrow function was falling out so rapidly.”

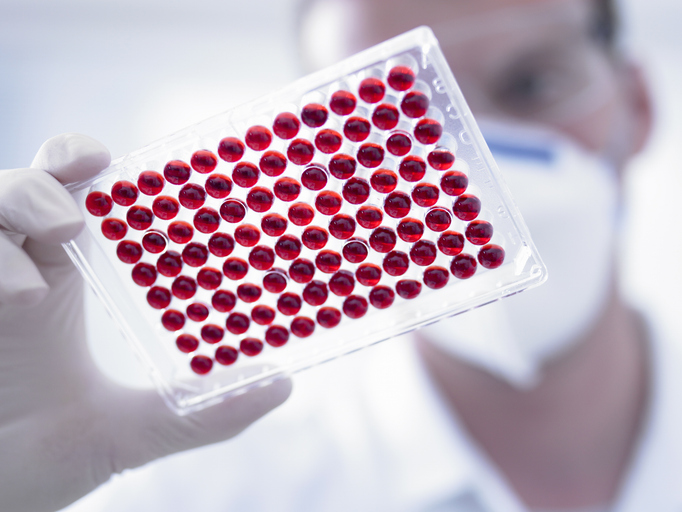

Medical explainer: What is aplastic anaemia?

Aplastic anaemia is a rare, serious blood disorder that sees the body failing to produce enough of all three types of blood cell – red, white and platelets. ‘Aplastic’ refers to the failure of the bone marrow to produce these vital cells.

According to the Aplastic Anaemia Trust, sufferers can be of any age, but are most commonly diagnosed young (between 10 and 20 years old) or as older people aged 60-plus.

With only around 100-150 people diagnosed in the UK each year – that’s only around two per million – the disease is classified as ultra-rare. It happens when the immune system attacks the bone marrow. Though it can caused by inherited genetic mutations, the condition can also develop for unknown reasons. Symptoms can include bruising easily, anaemia – causing a lack of energy – weakness and a susceptibility to infection. Aplastic anaemia can be treated using bone marrow transplants or immune-suppressing drugs.

“For many patients, having a transplant for aplastic anaemia is every bit as gruelling as receiving the same treatment for a blood cancer like leukaemia,” explained CEO of the Aplastic Anaemia Trust, Stevie Tyler. “However, AA patients have to deal with the additional burden of being diagnosed with a potentially life- threatening rare disease that no one has heard of. That’s why, as a tiny charity trying to raise awareness and support these patients, we’re so pleased to see Nick competing at this level,” she added. “It’s not only fantastic to see his recovery, it’s also brilliant for our community to have him raising awareness of aplastic anaemia.” Find out more at TheAAT.org.uk.

He was diagnosed with aplastic anaemia, a condition that means the body does not produce sufficient red blood cells. Like Topley’s hepatitis, it is an autoimmune disease, and it eventually transpired the two were connected. His treatment consisted of having T-cells removed to dampen his immune system, and it worked – he was in remission for two-and-a-half years, before symptoms began to return while on a holiday in Greece. Again, within weeks he was dependent on transfusions. This time, Topley’s condition had progressed to severe aplastic anaemia, and he ended up having a bone marrow transplant, the donor being his sister.

After that, he spent six weeks in isolation. “It was 40 days and 40 nights,” he says, raising his eyebrows at the biblical significance. “The worst thing was the food. You’re in this twilight zone,” he adds. “You’re a bit out of it because you’ve had chemotherapy and you’re on lots of drugs, and you’re just waiting for your numbers to change.” Topley’s numbers did eventually change, and he was able to go home to continue his recovery. After some months, he returned to work, although his recovery was derailed in a “horrendous” way by thyroiditis, for which the cure turned out to be huge amounts of pain- and psychosis-inducing steroids.

Topley overcame successive illnesses to reach top-tier fitness

The first triathlon

At this point, Topley still had no idea he would go on to become a dedicated, international medal-winning bike racer. His only bike may have been “made by Halfords 20 years ago”, but he had always been sporty, having played cricket, football and rugby to a good club level, and was pretty handy at running too.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Unsurprisingly, sports had fallen by the wayside over the past 10 years of Topley’s life. But the fit and active person inside was only biding his time to reappear.

It was in mid-2016, during one of the “old man’s coffee club” meets that Topley enjoyed with his mates Mike and Nick, that the idea of a triathlon to celebrate retirement cropped up, and he was chosen to take the bike leg. It was a case of, “Mike’s a serious runner, Nick’s a serious swimmer so who’s going to do the cycling? It looks like that’s you, Nick,” Topley explains. He began training on his old Halfords bike, starting more or less from scratch, as the 5km distance of that first training ride attests. “I can remember the first time I did 10 kilometres,” he says, “that was a massive ride.”

Sport Therapy: Spreading the word

Nick Topley’s bulging trophy cabinet has come as a happy side- effect of looking after his own well-being and his desire to raise awareness of transplantee sport.

As part of this drive, Topley is involved with Transplant Team Wales, which he chairs. He wants to spread the message about how much transplantees can benefit from being involved in sport.

“The important thing is that more transplant patients realise that exercise is good. It’s good for physical and mental well being,” he says. “It’s not the doctors’ job to recruit to sport, it’s the job of other transplant patients, government and sporting bodies.”

Giving the example of Welsh transplantees, of whom less than 2% compete in the Transplant Games, he says: “That means there are 1,950 transplant patients not competing in the Games. Would they like the opportunity to compete in the Games? Probably they would.”

Topley and a neighbour rode together all through that winter, often riding multiple laps of a loop around Barry’s three bays, and Topley quickly found himself growing stronger, he says. “It’s just the nature of somebody who’s been competitive before,” he says. “I get stronger and so I want to do more; I want to go up steeper hills, I want to go faster.”

In the end, Topley and his coffee buddies rode the Peguera triathlon in Majorca, in October 2017. It ended up being the first of what has become seven events and counting, but it placed him at the bottom of a major learning curve. “I looked more like a postman than a cyclist,” says Topley, recalling the upright position he used. “I think I did three hours 25 for 90 kilometres. But I was just delighted. I’d never done anything on a bike that hard. I was ecstatic when I finished.”

Topley’s racing career snowballed from there. Two years later in 2019 he achieved his first sub-three hour ride at Peguera, and rode his first Welsh Transplant Games too. The cycling events were originally planned to take place around the car park of a Tesco supermarket in Newport, Topley explains. “Several of us intervened and said, ‘Do you realise we’ll be doing speeds of 45 to 50kph? Thankfully, they moved it to Maindy Stadium.”

By then, Topley had traded in his old shed bike for a Giant TCR, and despite riding around on the lever hoods, he won a silver medal in the 5km time trial. “When it was posted that I’d won a medal, I was in tears,” he says. “It was a major achievement.” His participation in the road race didn’t go quite so well – “I was going back and back, I was fuming!” – but nevertheless it was a learning experience and he was hooked. He adds: “A big part of my story is the road race and how I’ve gone from having absolutely no idea, to where I am now.”

Transplant Games triumph

The following year lockdown struck and there were no transplant events, but Topley spent the time working on his cycling fitness with focused training sessions, “in a sensible, not just random order,” as he puts it. Since then, his Transplant Games participations have brought him much success, with time trial gold at the British Games in Leeds in 2021 (“the fittest I’ve ever been on the bike”) and bronze in the road race (“I led for 9.8 laps and then lost out in the sprint”). Those results helped him qualify to represent Team GB & NI for the World Transplant Games in Perth, Australia last year, which took the whole Games concept up another level. “You’re sitting in a stand with 5,000 transplant patients. It’s unbelievable,” he says.

On the technical and challenging Wanneroo motor circuit not far north of the city, Topley opened his account there with a time trial bronze, then a TTT gold, with two team-mates getting on for 20 years his junior. He followed that up with an impressive road race performance that saw him drop all-comers bar two breakaways to secure another bronze medal.

This year, Topley has a host of events lined including British Transplant Games, and European Transplant Sports Championships in Nottingham and Lisbon respectively, London to Paris and two half-Ironmans, including another crack at Peguera.

He cites cycling as key to his rehabilitation and recovery. “It’s clear from the scientific data that the fitter you are when you go into transplantation, the better you do – and the fitter you are afterwards, the better you do.” Cycling has become part of his “daily motivation”, as Topley puts it. “I come back, have a shower, and I feel fulfilled. It’s been massive in terms of my physical and mental well-being... hugely important.” By promoting transplantee sport awareness, Topley’s goal now is to help other transplantees feel those same benefits. And to win more medals, of course.

After cutting his teeth on local and national newspapers, James began at Cycling Weekly as a sub-editor in 2000 when the current office was literally all fields.

Eventually becoming chief sub-editor, in 2016 he switched to the job of full-time writer, and covers news, racing and features.

He has worked at a variety of races, from the Classics to the Giro d'Italia – and this year will be his seventh Tour de France.

A lifelong cyclist and cycling fan, James's racing days (and most of his fitness) are now behind him. But he still rides regularly, both on the road and on the gravelly stuff.