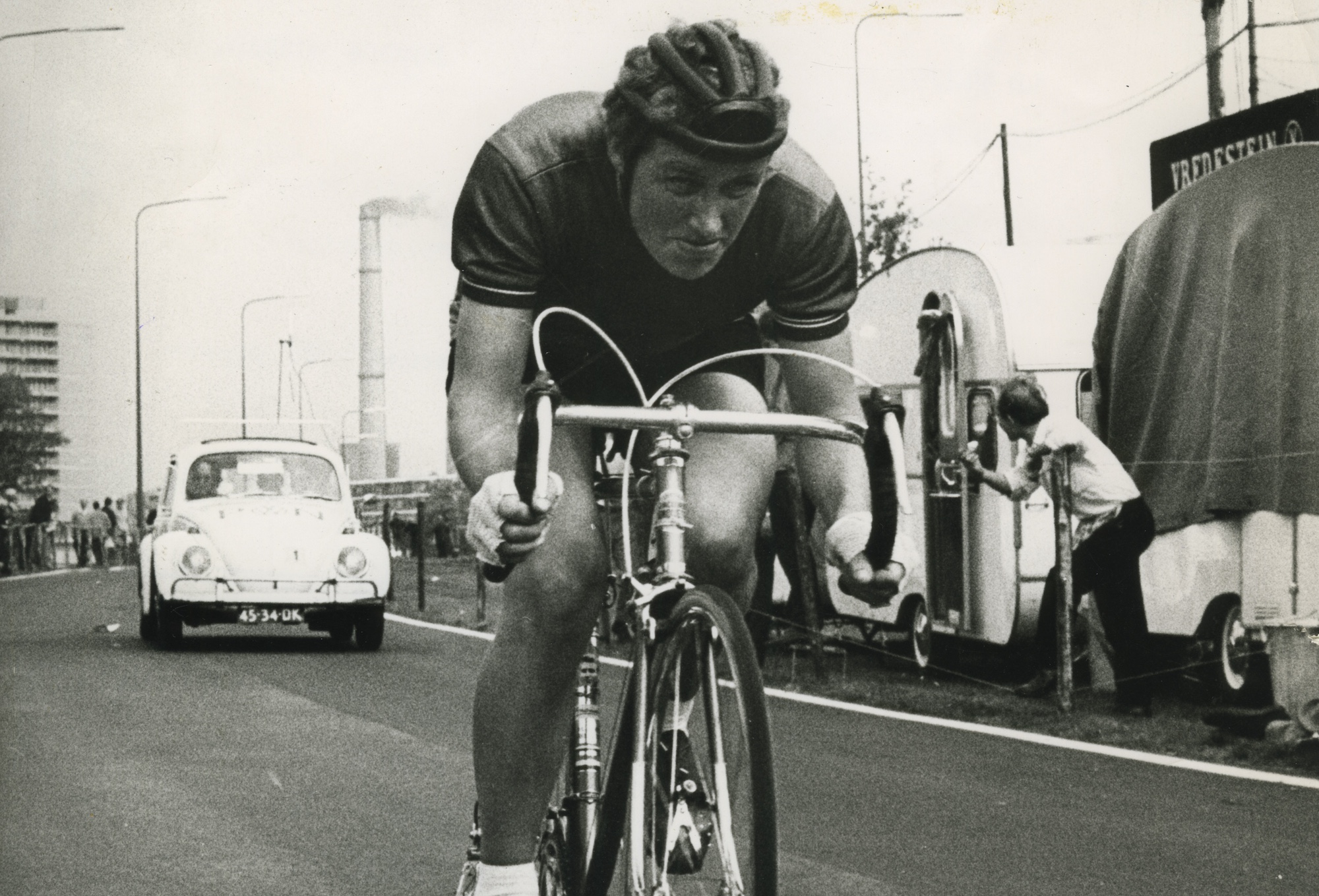

"Nothing stood in her way" - the Yorkshire woman who worked on a farm and was one of the greatest cyclists who ever lived

From the 50s to the 80s, Beryl Burton dominated British women’s racing. In a 2009 'British Legends' feature, Cycling Weekly looked back at her prolific career

In the end, her relentless drive was possibly what killed Beryl Burton, but during her lifetime it is also what defined her.

Even as a schoolgirl playing ball by herself in the playground she would set exacting standards. In her autobiography Personal Best, she explained that every time she failed to reach her target, it would result in an inward ticking off. "I would even bite the ball with frustration and annoyance," she wrote.

Her daughter, Denise Burton-Cole, thinks that more so than any physical attributes, Burton's gift was her determination.

"She just had her own ideas of what she was going to do and she did it," Denise recalls. "Nothing stood in her way."

The results produced by this determination were outstanding. In the history of British cycling, no one before or since has been quite so dominating. And while Burton's bread and butter was the domestic time trialling scene, where she ruled the roost for a whole quarter of a century, she also proved her ability on the world stage, winning no less than seven world road race and pursuit titles.

>>> From Burton to Armitstead: Britain’s road race world champions

Had the World Championships then included a time trial as it does now, who knows how many more world-beating performances the Yorkshire native might have produced. As for the Olympics: it's another case of what if? Women's cycling wasn't introduced to the Games until Burton was 47.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"We always talk: ‘What would Beryl have done today with the track at Manchester, all the equipment and support'," says Malcolm Cowgill of Burton's Morley CC.

"When you think about it, the Eastern Europeans were souped up to the eyeballs. How many gold medals did that cost her? Back then, the Women's World Road Race was run over ridiculous distances like 25 miles. If it had been what it is now - say 80 miles - she'd have been the last one standing. It'd be tailor made for her."

But history is what it is, and Burton's palmarès is staggering enough without any hypothetical aero-bars, training camps and sports psychologists (things she might have dismissed as ‘fancy fads' anyway).

Self-funded and without a formal coach, Burton won such an overwhelming number of honours that giving a definitive total seems a risky business. One might overlook an obscure team result somewhere. Or simply get the maths wrong.

Breaking the statistics down into more bitesize chunks, Burton was the national pursuit champion 13 times and won the road title on 12 occasions. Moving on to time trials, the numbers go up a whole other level. She was 18 times the national 100-mile champion, 23 times the national ‘50' champion and 26 times the 25-mile champion. Burton was already in her 40s when the Road Time Trials Council introduced a national 10-mile title. Yet she also won that four times.

>>>> Buy a Beryl Burton poster - in full flight

In addition to these titles, Burton was, for 25 successive years (between 1959 and 1983), the British Best All-Rounder. She set records dozens of times, reducing them over the course of her career by as much as 15 per cent. In 1963, she was the first woman to go under the hour for 25 miles, and subsequently bust the two and four-hour barriers for the ‘50' and the ‘100'.

All of these she significantly improved on. Most of her ultimate records stood for the best part of 20 years while disc wheels, skinsuits and faster conditions on dragstrip courses came along.

Sweet success

Although most of her records have now tumbled, Burton still holds the women's 12-hour record, set over 40 years ago in 1967. At 277.25 miles, Cowgill points out that it is a distance many men would still be happy with now. "Only the very best, people like [Andy] Wilkinson, have surpassed it," he says.

At the time it was absolutely phenomenal. Not only did Burton improve on her own 1959 figure by 27 miles, but she recorded a distance that for two years stood ahead of the men's record. Her ride also gave rise to time trialling's favourite anecdote.

One of Burton's most famous idiosyncrasies was offering witticisms to riders she caught. Dave Taylor, press secretary at Cycling Time Trials, remembers: "The only experience I had with Beryl was being caught by her in a ‘25' in Essex. As she passed me she said ‘Eh lad, you're not trying' where upon she disappeared up the road."

The story was no different in the Otley CC ‘12' when she caught Mike McNamara, who himself was on the way to recording a new men's national record - 0.73 miles shorter than the figure she set. In her book, Burton recalled the sympathy she felt as she approached the Rockingham CC rider: "Poor Mac... his glory, richly deserved, was going to be overshadowed by a woman."

Recognising the need to make a gesture as she passed, Burton offered him a liquorice allsort from a bag she had in her back pocket. "Ta love," McNamara had replied, then popped the sweet into his mouth. Years later, his club honoured that moment by presenting Burton with a giant version of the sweet at their annual dinner.

Stern stuff

Although Burton's autobiography demonstrates she clearly had a soft centre, her gritty determination and steely demeanour gave her a reputation for being "as hard as nails".

Cowgill says: "She wouldn't suffer fools, that was for sure."

Even her daughter admits she has to read the autobiography for some insight on her mother.

"She wasn't a person to talk a lot about her career," Denise recalls. "In fact, she wasn't a person to talk a lot at all. She thought it was a waste of

energy, perhaps!"

Family time

Of course no one knew Burton as well as her husband Charlie, who still regularly gets out on his bike at 80 years old.

The pair had met after Beryl - who had a childhood affected by a nervous disorder - left school and started working in a clothing factory.

"I used to go to work on a bike," he recalls. "She said ‘I'm gonna get one of those' and I said ‘oh yeah', and didn't think anymore about it. But we started chatting a bit more and I lent her one of my bikes and she used it to go up to the [cycling] club or go dancing at the dancehall. From then on, we just started going out cycling.

"First of all, she was handy but wasn't that competent: we used to have to push her round a bit. Slowly she got better. By the second year, she was one of the lads and could ride with us. By the third year, she was going out in front and leading them all. By then it was 1956 and she decided to do a bit of time trialling because I was dabbling at it."

As Beryl began to show her potential, Charlie's own cycling took a backseat.

"I know she wouldn't have been as successful without my father there," says Denise. "He cycled to work and back but he gave up everything else. He did the bikes, drove her about and did a lot for me too, when I was at home. He's as much a champion as her, really. Her success was shared between them."

Having grown up going touring in a sidecar attached to her father's bike, and later riding with her parents on club runs, Denise also became an international cyclist.

Quite uniquely, in the early 70s, the mother and daughter were joining each other for national team trips together. In 1973, Beryl won the National Road Championship ahead of Denise. Three years later, their positions were reversed and the mother gave rise to another of those legendary anecdotes by refusing to shake hands with her daughter on the podium.

"I was too overjoyed at winning, and I didn't take any notice of anything like that," recalls Denise, charging that most of the fuss was media hype.

In her book, Beryl offered an explanation: "I thought Denise had not done her whack in keeping the break away and once again I had ‘made the race'[...] It was not a sporting thing to do [...] I can only plead I was not myself at the time."

Fighting fit

The mother and daughter soon reconciled but, despite getting older, Beryl Burton's competitive spirit never did seem to fade.

"She was still trying to achieve things when her health deteriorated in the last 10 years of her life," recalls Charlie. "Her times were getting slower in the time trialling... so she was never happy or content with that. She was always trying to thrash herself back into shape. She was still pushing right up to the end; trying to get back to her former glories."

Inevitably, this all proved too much. One week short of turning 59, in May 1996, Burton - in whom doctors had always observed a curious heart rhythm - headed out to deliver some invitations for her birthday party. Those were the last pedal strokes she'd ever make. On her bike, on roads close to her Yorkshire home, Britain's most prolific racing cyclist collapsed and then died.

"I would have thought it was all the pushing she'd done to herself both mentally and physically," says Denise. "Your body eventually says it's about time you should rest, but she didn't. She did more than anybody. I remember when she used to train she'd do more miles than was ever needed. That was her. She wouldn't have done anything else. Pushing her body was the way she did things."

Beryl Burton's Book of Records

10 miles: 21:25 (1973) stood for 20 years

25 miles: 53:21 (1976) stood for 20 years

30 miles: 1:08:36 (1981) stood for 10 years

50 miles: 1:51:30 (1976) stood for 20 years

100 miles: 3:55:05 (1968) stood for 18 years

12-hour: 277.25m (1967) stood for 50 years

Beryl Burton: Highs & Lows

Charlie Burton reflects that he has so many fond memories of his wife winning titles that some of them blur together. However, he'll never forget her first world pursuit title win in Liège.

"They didn't think she'd had enough competition on the track for sending over to the Worlds, so at first she was a non-travelling reserve," he says. "Then they decided to send her as a travelling reserve and then she got there and won it."

Among other fond memories was her appearance at the Grand Prix des Nations where she was given a ride against the best male professionals of the day.

Charlie also recalls them going to meet the Queen at Buckingham Palace and being rather suspiciously eyed by security when they turned up in a Russian-built car.

"The one that still sticks out in everybody's mind is the 12-hour," he concludes. "She was just on form and going like a rocket. Nobody could touch her that day, not even the [men's] British champion."

In the final pages of her autobiography Burton succinctly sums up a number of reflections. The subsection entitled ‘regrets' is the very shortest of these. It simply reads: "Not taking the Hour record. Or that ‘24'". In Milan, for the women's Hour record, weather conditions and lack of funding conspired against her.

As for her crack at the National 24-hour record, Charlie recalls: "By then her joints were going, but she ignored it. In hindsight she put in too many miles [training] for the state of her hips, back and legs. Of course, she was leading the field for the first 300 miles, but her legs seized up and they were just like boards. We couldn't move them or anything. All the veins in her legs were like solid pipes - so we just had to lay her in the car."

Beryl Burton: The Ultimate Amateur

Beryl Burton was resolutely proud of her amateur status, and in 1960 consistently declined the advances of the Raleigh Bicycle Company, which was offering a contract with a view to her attacking place to place records.

Instead, the mother of one continued working. When racing commitments started to interfere with the regularity of office positions, she moved to a job on a rhubarb farm run by fellow cyclist Nim Carline.

Although in the summer both Burton and Carline could afford to take the odd week off, in the winter it was often 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.