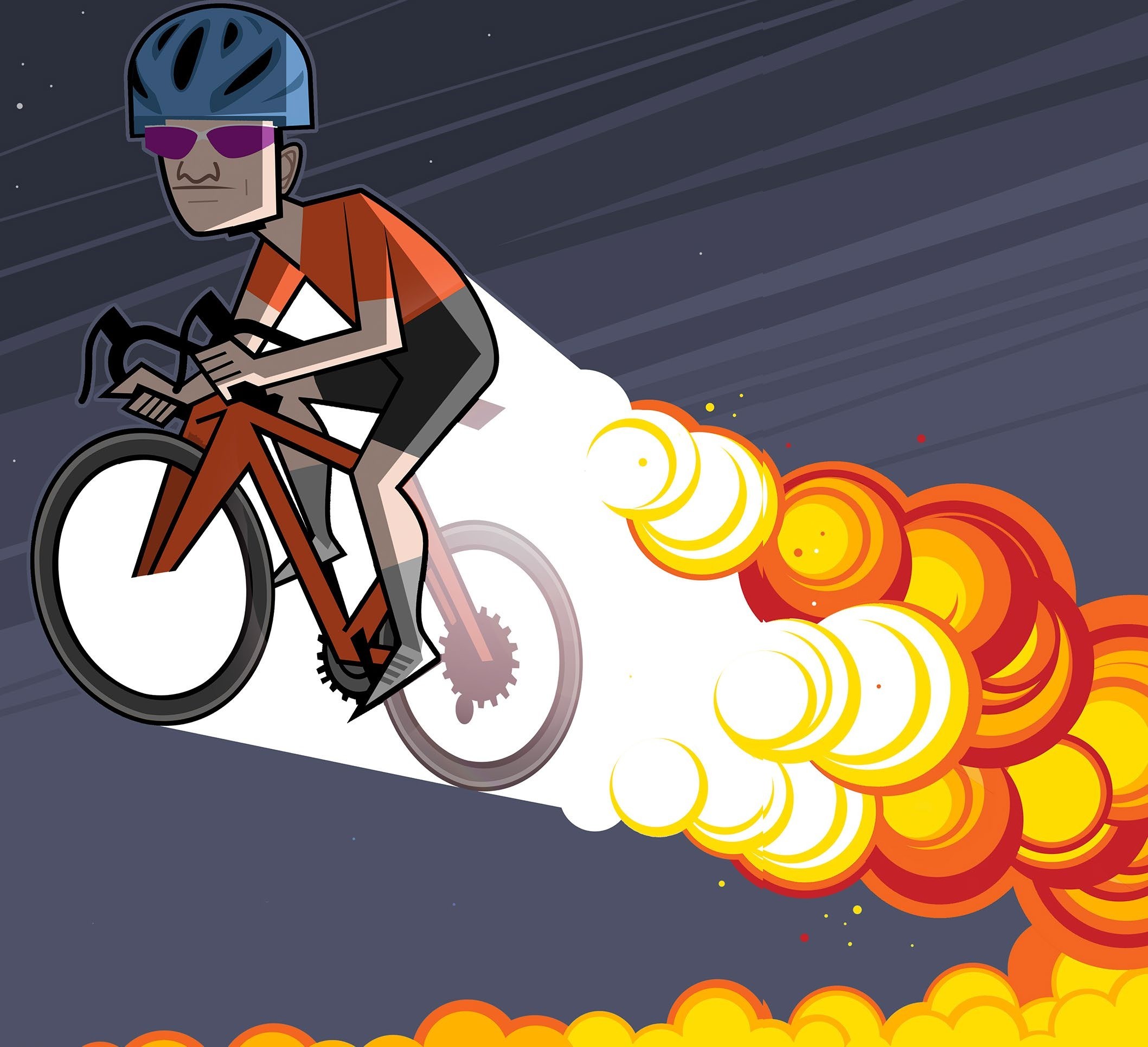

I'm a psychologist who got singed by cycling burnout – here's how to stay on the right side of the fire

Cycling ignites passion, but too much pressure and expectation can burn it away. A psychologist with personal experience of playing with fire tackles the delicate issue of burnout

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Two days after Christmas 2022, I woke up covered in bandages. The day before, I’d had a mechanical issue mid-sprint during a training ride and went over my handlebars at 52kph (32mph). I’d gone to A&E but spent only about five minutes there before deciding I would manage the injuries at home – possibly a mistake. What hurt most was that I had just begun a training de-load after three months of intense build-up to the Australian National Championships elite road race, which was only two weeks away.

Four days later, on New Year’s Eve, I was in my bathroom with the tumble dryer on, no fan, in the middle of the Australian summer, completing my heat acclimatisation training. Sweat dripped through my bandages and onto the blood-soaked floor. I made it to my target race, but immediately after began experiencing anxiety, a lack of energy, detachment and irritation. It didn’t feel like a temporary low; it felt like I was done with cycling. I’ve kept riding since then, but looking back, what I experienced was burnout. Context is important here. I was 37 at the time, a decent-level amateur cyclist, and working full-time as a clinical psychologist. This isn’t a story about me, but I recount that episode because it shaped my interest in burnout in elite sport, particularly in cycling.

Most people have some idea of what burnout is, but the term is often used trivially. Burnout isn’t just tired legs or a bad training block. In sports psychology, it is defined by three interlinked dimensions: a persistent sense of emotional or physical exhaustion, a reduced feeling of accomplishment, where your efforts seem to count for nothing, and a creeping sense of detachment from the sport you once loved.

In cycling, burnout can show up as declining performance, joyless racing, loss of motivation, poor sleep, flat mood, irritability, and wanting to stop altogether. However, stepping away from cycling doesn’t always mean burnout. Some riders walk away for safety, lifestyle or identity reasons, and the line between choice and collapse isn’t always clear. I was keen to find out if burnout affected professional, development and amateur riders in the same way – and whether it’s a growing trend?

Cycling’s burnout crisis

After the 2025 Tour de France, Tadej Pogačar, despite seeming to hold the cycling world in the palm of his hand, suggested he might retire after the 2028 Olympics, before his 30th birthday. Australian sprinter Caleb Ewan stepped away at the start of this season despite a new contract with Ineos Grenadiers, and more recently, Louis Kitzki, a 21-year-old Alpecin-Deceuninck development rider, retired after witnessing two fatal crashes. Before them, Tom Dumoulin, Marcel Kittel and Taylor Phinney all left the sport in their prime, citing mental and physical exhaustion.

Cycling has always been brutally demanding, but this recent wave of early exits points to something deeper. At first glance, the decision to quit may be confusing to those who envy the pro lifestyle: being paid to train and race, the sponsors, structure, and the adulation of fans. Yet those ingredients create risk, and success becomes a burden when it feels like an obligation. The modern style of racing doesn’t help. Flat-out from the flag drop, with constant attacks, endless media duties and tightly packed calendars, even the best riders may struggle to stay grounded.

When the pressure gets too much, joy can turn to dread

I spoke to a development rider we’ll refer to as James (not his real name), who moved to France chasing the dream of turning pro and quickly realised it wasn’t for him. He spoke about how the lifestyle “cracked” him. There was no room for anything else in life bar cycling, and the bike – once an escape – became a trap. He told me how eventually he couldn’t “escape the escape”. Like Kitzki, mentioned above, James was disturbed by the risks. He told me how races halted only when no more ambulances were available, and how it was a culture in which sometimes it seemed the events mattered more than riders’ lives. James eventually stepped away and has rebuilt his love of cycling recreationally. Returning home, he noticed immediate improvements in his physical performance too: “In terms of my head directing my legs, there was loads of change,” he said.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“SETBACKS BECOME EXISTENTIAL THREATS”

For James, professional cycling was a toxic working environment. Short contracts, limited agency and little say over conditions often leave riders vulnerable. His story highlights how precarious the U23 and Continental tiers can be. Young athletes, often barely out of school, are thrust into high-pressure environments abroad, with language barriers, relentless competition and minimal psychological support. When being a rider becomes the primary locus of identity, setbacks aren’t just disappointments – they are existential threats.

This is where Self-Determination Theory, a model in motivation psychology, can be useful. The model identifies three key needs for sustained effort: autonomy (having choice), competence (a sense of mastery), and relatedness (belonging and connection). When these are absent, the risk of burnout rises. Development and professional teams need to grow not just talent but trust, maturity and meaning for their riders. The riders who are offered the greatest foundation for self-determination are better able and more willing to continue in the sport.

Self-determination can take many forms, and ex-pro Yanto Barker explained that, when he started cycling, he was racing his way out of poverty. He described how, for him, the pressure of the sport was less than the pressure of his early life. It is his belief that many who pursue high-level performance are also working through their own trauma, not always in a negative way. Racing gave him purpose. “I loved racing, I loved who it made me,” he told me. To avoid burnout, Yanto viewed motivation as a luxury, focused on the present and developed his approach by learning from others and working on himself. He described how burnout is often the result of “not being in the moment, and catastrophising about the future.” Since retiring in 2016, Barker has reflected on cycling as a space to think and a vehicle for problem-solving in his work as CEO of clothing company Le Col.

Jack Rootkin-Gray, in his second year at EF, draws a distinction between being burnt out and simply being unhappy with circumstances or performance. “When I’ve felt burnt out, it’s different to when I’ve felt unsatisfied,” he said. He described a period, earlier in his career, of feeling unmotivated, and how he found ways to reconnect with joy. His advice to others in a similar predicament is to “imagine you were the most motivated you could be, how much energy you would have and how much you would enjoy your job.” He described how “to get the best out of my life, I have to be having fun.” He finds small changes – turning the power meter off, trying new tech or switching routines – can help keep burnout at bay.

Amateurs also at risk

Burnout isn’t limited to the professionals. In fact, many cases occur in the amateur ranks, though they receive little attention. They may be riding purely for the love of it, but that love can be curtailed. Sometimes amateur riders push themselves harder than pros: 20-plus-hour weeks on top of a full-time job, chasing race results that only their immediate rivals notice. For some, it’s meaningful. For others, it becomes a grind – especially when life gets in the way. However, for many amateurs, stepping back can feel like failure. If your identity has over many years become wrapped up in being the ‘fit one’ or the ‘first-cat racer’, it’s hard to admit when you’re struggling. Social media magnifies this. With so many people posting ride data online, it can feel difficult to break the cycle.

“CONNECTION, IDENTITY AND JOY MATTER AS MUCH AS FORM OR FITNESS”

Some amateurs told me how the trickle-down effect of “marginal gains” is having a corrosive effect. What once felt free now carries pro-level pressure. Toby Langstone, 32, a team-mate of mine on the Le Col race team, described it as a slippery slope: “Before you know it, you’re going on a Saturday ride or racing with people who are sleeping in oxygen tents” and “running TT tyres on your road bike during the winter” to keep your speed up. Josh Kent, 30, another team-mate, told me he has felt the need to ride for 12 to 15 hours per week just to be adequately fit to compete. For many, this creep erodes the joy, freedom and spontaneity that drew them to the bike in the first place. Tim Strickland, 30, who rides for GFTL, spoke about how acceptance and finding meaning in how you ride are the key to sustainability in the sport: “You’ve got to find your level and be happy with what that brings.”

Writing this article at the end of the amateur season, I was struck by how many people felt they were experiencing burnout in some way. Through these conversations, I have come to understand that burnout affects athletes at all levels, with different causes and implications from one rider to the next. The key to sustainability is finding a way to make riding meaningful to you. And if you do find yourself in a hole, the real challenge – and the real victory – is learning how to climb out and fall back in love with the bike again.

Burnout in cycling is real and apparently rising, but it isn’t inevitable. The pressures for amateur racers aren’t so different to those affecting pros. By listening to riders, supporting them as people as well as athletes, and fostering meaning at every level of the sport, we can build a culture where cycling becomes a microcosm of life – a place where people can find their own way to keep their passion alive.

For me, that lesson began on a bathroom floor in Australia, bandaged and broken. At the time, I thought I was done with cycling. What I’ve since learned from pros, development riders and amateurs alike is that connection, identity and joy matter as much as fitness or form. The goal is not to deny or ignore struggle, it’s to stay connected to one another in a compassionate, joyful way – even in a sport built on doling out pain to your rivals.

How to bounce back from burnout

In athletes, burnout often starts subtly: declining performance despite training, joyless racing, loss of motivation, poor sleep, flat mood and irritability. Understanding burnout requires consideration of multiple aspects of a rider’s experience. In the therapy room, I often explore four questions:

● When did you start feeling like this?

● What are you really chasing?

● Who are you if you aren’t cycling?

● When will you know that you’ve done enough?

Treatment for burnout involves the physical components of rest and recovery, but also reconnecting to meaning. Quoting the philospher Nietzsche, author Viktor Frankl wrote: “He who has a why can bear almost any how.” That line is especially potent in cycling. Sometimes the solution isn’t to stop riding but to ride differently. Let go of the numbers, try some new tech, use cycling to do your problem solving, or seek connection over competition. Perhaps we need to be willing to have seasons in life as well as in sport.

As described above, riders who reconnect with meaning – whether through competition, mastery or community – recover more fully. It could be useful to write and reflect on the above questions. And as always, prevention is better than cure.

Burn bright, don't fade away

If burnout is becoming more common in cycling, it’s not because riders are weaker. It’s because the demands have changed – and because we’re finally talking about it. So how can we protect riders at all levels from burnout?

For teams: provide mental health support as standard, not only in an emergency; create proactive cultures where honesty is rewarded, not punished; celebrate resilience and growth as well as results.

For coaches: recognise signs of demotivation early; avoid over-glorifying sacrifice; build rest into plans; focus on autonomy, purpose and living in harmony with a rider’s values, not only achieving the best performance.

For riders: stay connected; know your why - or be willing to find a new one; don’t wait until you feel broken to ask for help; try new ways to reframe cycling – make it fun, novel and engaging in whatever way you can; and remember that stepping back doesn’t necessarily mean you’re giving up.

This article was first published in the 25 September 2025 print edition of Cycling Weekly magazine – available to buy on the newsstand every Thursday (UK only) while digital versions are available on Apple News and Readly. Subscriptions through Magazine's Direct.

Dr Steve Mayers is a clinical psychologist and bike racer based in London: drstevemayers.com

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.