'Don't die of embarrassment': Why men need to check their risk of prostate cancer – and not worry that cycling is a factor

Sir Chris Hoy’s stage-four diagnosis has put prostate cancer under the spotlight among cyclists. Cycling Weekly tackles the confusion around risk factors and screening

David Bradford

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Sir Chris Hoy revealed that he had been diagnosed with stage-four prostate cancer in September 2023, aged just 47, the shockwaves reached far beyond the velodrome. Here was Britain’s most decorated Olympian – the embodiment of supreme fitness – confronting a killer disease that affects one in eight men in the UK. “I didn’t think about what the potential outcomes of going public with my diagnosis might be,” says Hoy, “but [since then] I’ve heard from people who have gone and had a PSA test off the back of my diagnosis – despite having had no symptoms – and been diagnosed, catching it early enough to treat and cure it.”

Now, two years on, Hoy has expressed "disappointment and sadness" at the UK National Screening Committee's recommending against a nationwide prostate cancer screening programme except for men between the ages of 45 and 61 who have specific genetic mutations. The experts advised that wider screening would "likely to cause more harm than good". Drawing on his own experience, Hoy said: “I know first-hand that by sharing my story following my own diagnosis two years ago, many, many lives have been saved. Early screening and diagnosis saves lives. I am determined to continue to use my platform to raise awareness, encourage open discussion, raise vital funds for further research and support, and to campaign for change.”

Hoy’s decision to go public with his terminal diagnosis has had a remarkable impact. According to Prostate Cancer UK, in the two months following his announcement, 286,000 men checked their prostate cancer risk online, and 38,000 of them indicated a family history of the disease. For a condition that often develops silently, that surge in awareness is likely to translate into lives saved. For many cyclists, the news raised uneasy questions. Could years in the saddle somehow increase the risk of prostate problems? Or is that just another piece of cycling mythology? To separate myth from medicine, Cycling Weekly speaks to leading experts and an amateur rider for whom Hoy’s story powerfully struck a chord.

Article continues below

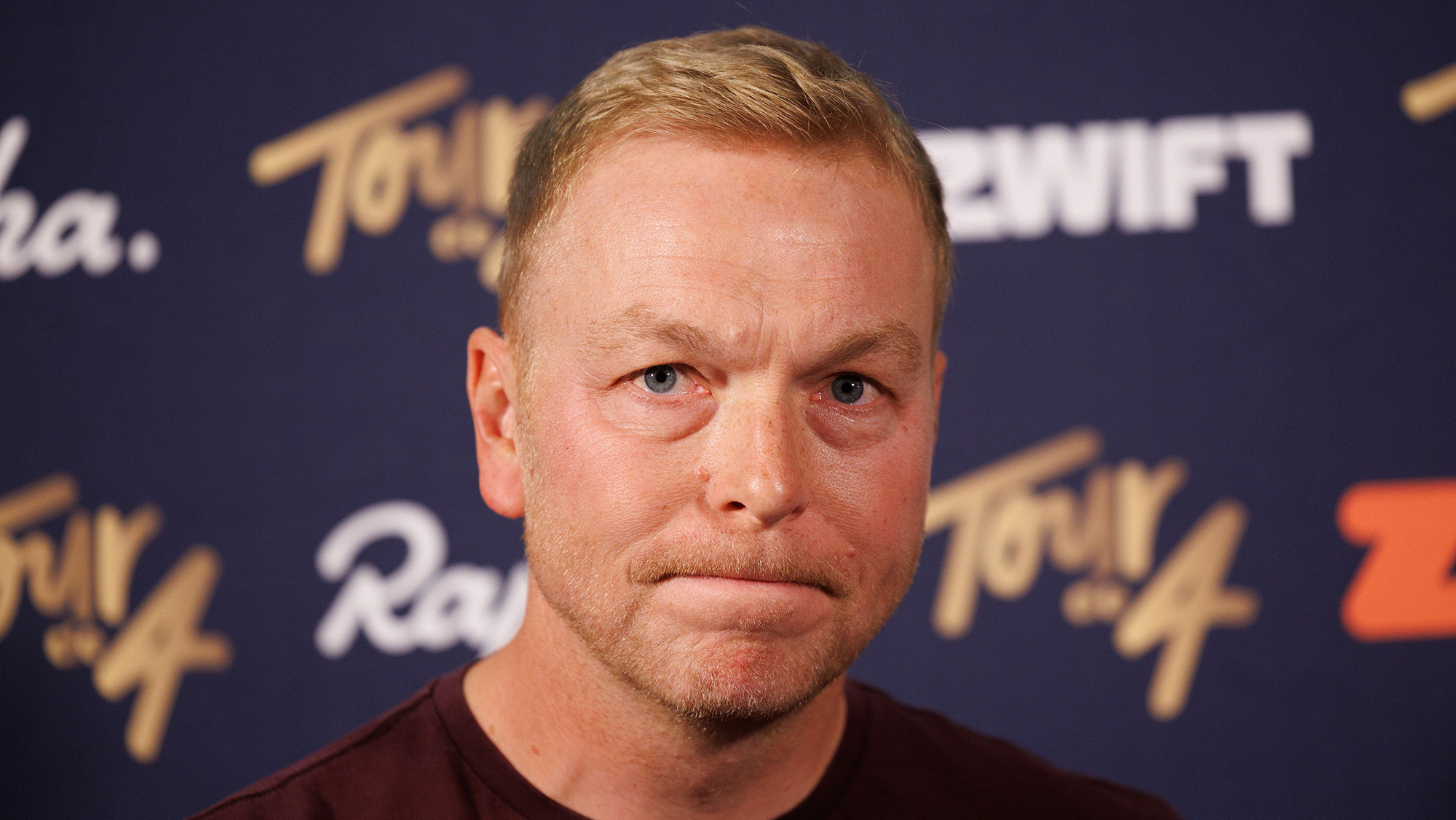

Chris Hoy speaks during an Andy Murray event in London, June 2025

Shock diagnosis

When Northern Irish cyclist Michael Currid, now 71, went for a routine blood test in his early 60s, he had no idea it would uncover an aggressive prostate tumour. “I had no symptoms,” he says. “Maybe a bit of a slow flow when I went for a pee, but nothing that worried me. I was going for some tests and my wife told me, ‘Get a PSA test while you’re at it.’ A friend of ours had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and it was at the front of her mind. That advice probably saved my life.” Currid was already fit and active, having taken up cycling at 60 after years in motorsport. “I joined the local Bann Wheelers Cycling Club in Coleraine, and loved it,” he says. “Two years later I was riding in the Alps for the first time, climbing all day and loving every minute. I was probably the oldest in the group, but I kept up fine.” It was only after returning home from an overseas riding trip that he noticed a dip in energy. “Towards the end of the season, I just felt a bit weak on our Thursday rides,” he recalls. “So I thought I’d better get checked.”

Currid’s prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level came back slightly raised. Further tests confirmed an aggressive tumour. “When the doctor said, ‘You’re going to need surgery,’ it hit me – this is serious.” With no specialist robotic surgery available in Northern Ireland at the time, Currid travelled to Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge.

“They told me being a cyclist would help with recovery,” he says. “I had the operation on 31 May 2017, and four weeks later I was back on the bike. Probably too soon – but that’s cyclists for you!” He decided against chemotherapy or radiotherapy. “The surgeon said he couldn’t guarantee clean margins because the cancer had broken out slightly, but he thought he’d managed to get it all,” he says. “I decided to wait and see. Eight years on, my PSA is thankfully still undetectable.” Cycling, says Currid, played a crucial role both physically and mentally. “It gave me something to focus on. If I hadn’t been riding, I probably wouldn’t be here today,” he says. “Cycling is the best pill you can take.”

“IF I HADN’T BEEN RIDING, I PROBABLY WOULDN’T BE HERE TODAY”

Ride without fear

It’s easy to see how myths around cycling and prostate health take hold. Hours in the saddle can cause numbness, perineal pressure, or discomfort in the vicinity of the prostate. But that doesn’t mean cycling causes prostate cancer. “There’s no evidence of a direct causal link,” says Mr Chris Ogden, a prostate surgeon at the Princess Grace Hospital, part of private hospital group HCA Healthcare UK. “The so-called ‘PSA jump theory’ – the idea that cycling raises PSA levels and leads to false alarms – has also been disproved. A large study from Greece involving around 8,400 cyclists found no higher incidence of prostate cancer overall compared with the general population.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Cycling is a risk reducer rather than a risk factor

While the Greek study did show a slightly higher rate among high-mileage cyclists compared to weekend riders, in Ogden’s view this is because cyclists tend to be fitter and more proactive about health screening. “Fit men are more likely to get tested and therefore diagnosed earlier. It’s not cause and effect, it’s association.” He adds that exercise is overwhelmingly protective. “Even in men with advanced prostate cancer, regular physical activity is beneficial. It reduces free radicals and oxidative stress, which helps slow disease progression. The idea that ‘bashing the prostate on a saddle’ causes cancer just isn’t supported by science.”

The saddle myth busted

Lisa Hilder is a prostate cancer specialist nurse with more than two decades of experience. “There’s no strong evidence linking cycling to prostate cancer,” she agrees with Ogden’s assessment. “At most, it can temporarily affect PSA levels.” (A short-term rise in PSA in the hours after exercise isn’t uncommon, as vigorous activity can release more PSA into the blood). “That’s why we suggest men avoid cycling for a few hours before a PSA blood test,” adds Hilder. Mild pelvic discomfort after long rides, she adds, is common and usually harmless. “If you’re getting pressure or numbness, it’s more likely due to your saddle set-up than your prostate. Check that your saddle supports your sit bones rather than pressing into your perineum. Modern saddles with central cut-outs or more flexible designs can make a big difference.”

Ogden similarly suspects that saddle shape has contributed to false fears around health risks. “My father was a GP and used to talk about ‘sensible saddles’ – the wider ones that take weight off the perineum. Some racing saddles focus all the pressure in the wrong area. If you’re getting symptoms, look at your set-up, but don’t panic.” While there’s no reason to fear even narrow, race-type saddles, men do need to pay attention to risk factors – and that means looking beyond cycling.

Risk factors

“The biggest risk factor is age,” says Hilder. “Men over 50 are most at risk, and if a close relative – a father, brother or uncle – has had prostate cancer, your risk is higher.” For white men, the lifetime risk is around one in eight. For Black men, it’s one in four. “Those are stark statistics.”

Your chance of getting prostate cancer may be even greater if your relatives were under 60 when they were diagnosed. Ogden points out that family history on the mother’s side can be relevant too. “If your mother or sisters have had breast or ovarian cancer, particularly linked to BRCA gene mutations, your own prostate cancer risk goes up,” he adds. “That’s something a lot of men don’t realise. It’s not just your father’s health history that matters.”

Prostate Cancer UK has long campaigned to improve testing accuracy and accessibility for men at risk of the disease. The charity’s Transform trial, announced in 2023, is a long-term study exploring the most effective combination of PSA tests, fast MRI scans, and genetic screening to detect prostate cancer earlier and more accurately. “The challenge has always been finding a way to detect prostate cancer early without overdiagnosing or overtreating men who don’t need intervention,” says Hilder. “The new generation of multiparametric MRI scans has been a game-changer – they’re much more accurate, so fewer men need unnecessary biopsies.”

Ogden agrees: “The European screening trial published recently showed a 13% reduction in mortality. That’s significant. It means prostate screening is comparable to breast and bowel screening. The next step will be national adoption, but we have to balance early detection with avoiding overdiagnosis or unnecessary anxiety.” Both experts believe targeted screening – focusing on men at higher risk due to family history or ethnicity – is the most efficient approach for now. “Men over 50 should talk to their GP about a PSA test,” says Hilder, “and if you’re at higher risk, start at 45. The test is quick, simple and free on the NHS.”

Men are advised to check their risk and, if appropriate, take a PSA test

Be proactive

One common barrier to men getting tested has been fear or embarrassment about the traditional digital rectal examination (DRE). That barrier is now largely gone. “The rectal exam is no longer routinely required to diagnose prostate cancer,” says Hilder. “It’s mainly used to assess prostate size for men with urinary symptoms. For cancer risk assessment, a PSA test and, if needed, an MRI are far more informative. Men can rest assured that they can speak to their GP without worrying about that.” The implication is clear: don’t die of embarrassment.

In many cases, early-stage prostate cancer has no symptoms, which is why risk awareness is so crucial. When symptoms do occur – weak urine flow, increased frequency, or difficulty emptying the bladder – they’re more often related to an enlarged prostate than to cancer. “If you notice any changes, don’t ignore them,” says Hilder. “But remember, most prostate cancers are picked up through proactive checks rather than symptoms. The earlier it’s found, the easier it is to treat.”

“THE RECTAL EXAM IS NO LONGER ROUTINELY REQUIRED”

Where does that leave cyclists? In a strong position, according to the experts. “Cyclists are often fitter, leaner, and more aware of their health – all of which are protective factors,” says Ogden. “Moderate exercise is good for the prostate and for general health. The only caveat is that extreme endurance training can, in rare cases, suppress the immune system – but for 99% of riders, cycling is a huge positive.” Staying active, according to the experts, helps with everything from maintaining a healthy weight to improving recovery after surgery or treatment.

Michael Currid is convinced that his passion for cycling is part of the reason he’s recovered so well. Far from slowing down, Currid has gone on to become a decorated racer in the over-70 category. “For my 70th, I thought, what will I do? So I entered the Gaelforce cycling event in Galloway [in Scotland]. On the back of that, I qualified for the world finals in Denmark. In the past year, I won three Ulster Championship medals, a gold, silver and bronze, and I won the 70s category in the Ernie Magwood Super Six time trial series.” Currid has helped raise more than £35,000 for Prostate Cancer UK through rides and raffles with his club Bann Wheelers Cycling Club. “If my story gets one man tested, that’s all that matters,” he says. “Far too many men wait for symptoms, and by then it can be too late. The PSA test isn’t perfect, but it’s the best thing we’ve got. If I hadn’t had that test, I wouldn’t be talking to you today.”

Thanks to the PHA Group for facilitating our interview with Mr Chris Ogden. (thephagroup.com)

CW gets tested

Reminded of a family history of the deadly disease, CW’s senior editor David Bradford takes the test.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men: one in eight of us will be diagnosed with it. A family history of the disease raises the risk even higher. If one or more first-degree relatives (father, brother or son) have had prostate cancer, your risk can be raised from about 12% to 30% or even higher. These men are advised to take a yearly PSA test from age 45.

Editing this feature reminded me that two second-degree relatives (my paternal grandfather and uncle) died from the disease, which raises my risk to about 20%. Those with a raised risk – check yours via prostatecanceruk.org – can get a free annual PSA test on the NHS. Being just below the age threshold, at 43, I decided to order one via Medichecks (medichecks. com), and reassuringly the result came back within normal range. Still, it underlined the importance of getting into the habit of annual testing.

According to prostate cancer specialist Chris Ogden, all men should take a yearly PSA test from age 50. The case against PSA testing – and why there is no nationwide testing programme – revolves around the risk of false positives and unnecessary biopsies. However, these days most men found to have a raised PSA level then have an MRI scan, and only have a biopsy if it’s deemed necessary.

Red flags and how to check your risk

You can check your risk of prostate cancer in just 30 seconds at prostatecanceruk.org/risk-checker.

Key prostate problem warning signs to look out for:

● Difficulty starting or stopping urination

● Weak or interrupted urine flow

● Needing to urinate more often, especially at night

● Blood in urine or semen

● Pain or discomfort in the lower back, hips, or pelvis

● Erectile difficulties or unexplained fatigue

Note: These symptoms don’t always mean cancer – they can also be caused by benign prostate enlargement or infection – but they should always be checked by a GP.

This feature was originally published in the 27 November 2025 print edition of Cycling Weekly magazine – available to buy on the newsstand every Thursday (UK only) while digital versions are available on Apple News and Readly. Subscriptions through Magazine's Direct.

Rob Kemp is a London-based freelance journalist with 30 years of experience covering health and fitness, nutrition and sports sciences for a range of cycling, running, football and fitness publications and websites. His work also appears in the national press and he's the author of six non-fiction books. His favourite cycling routes include anything along the Dorset coast, Wye Valley or the Thames, with a pub at the finish.

- David BradfordSenior editor

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.