Smartwatches act like a 'military drill sergeant' on your wrist - it's ok to ignore them when they claim you're 'unproductive'

Fitness gadgets use very emotive language, but should we be allowing them to press our buttons? Dr Josephine Perry investigates

“You slept poorly, take a rest day.” I’ve spent months training and now finally I’m on the start line of my biggest race of the year – when my watch flashes up a most unwelcome message. I feel fine and I know – from the studies in this area – that one night’s poor sleep does not equate to poor performance. But that little message nudges my brain from confidence to concern: can I push hard for four hours despite a gadget designed to assess my physiological indicators telling me a decent performance is off the cards? Are our wearables too often using misleading, even counterproductive language?

Though at the time I admit I was tempted to lob my watch into a bin, I resolved that there were still some big benefits from using wearable fitness devices. They can arm you with data to improve your health, fitness and wellbeing; facilitate your engagement with others when you share the data on socials; improve your mastery as you see which skills or efforts get you better outcomes; help you correlate data with feel so you can benchmark your perception of effort; and they can, if they match your motivation style, push you into training more effectively. But none of that excuses the start-line faux pas.

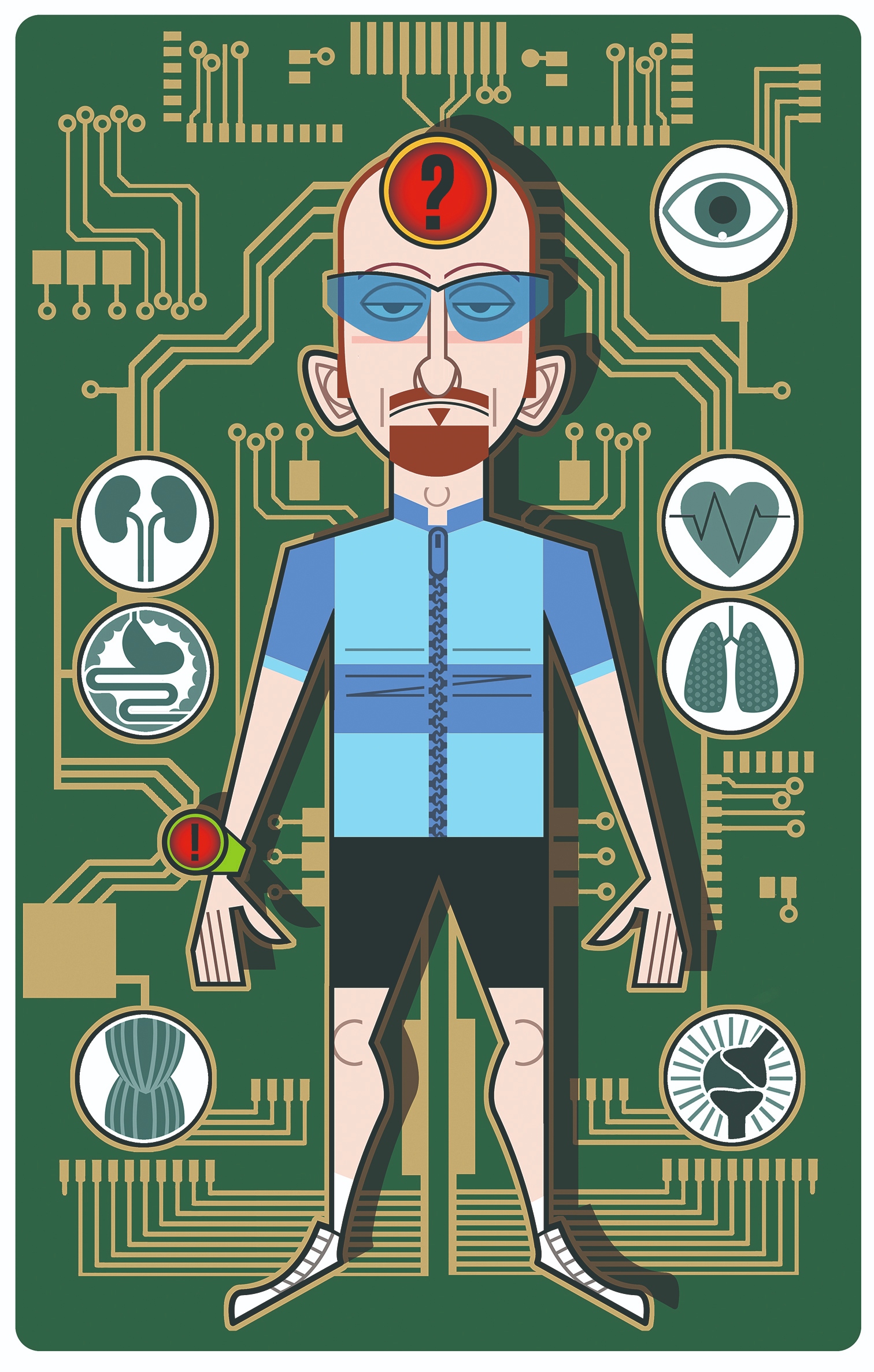

With 1.1 billion wearable owners around the world and 318,000 health apps collating, interpreting and communicating biodata back to users through short statements, illustrations, progress bars, virtual badges, vibrations, sounds, awards, graphs and emojis, this technology is clearly very popular. However, wearables are prone to communicate data in ways that can seem discouraging, even hostile. A gadget might be able to work in real time, with greater speed – and sometimes accuracy – than a coach, but to what end? If that data undermines your confidence through a blunt, irrelevant or misinterpreted communication, it’s doing more harm than good.

Language gap

Many of the developments in wearable technologies have come via the military, space and medical industries, where a neutrality and bluntness of language is acceptable between professionals. Rolling this out to athletes, including amateurs and novices, requires more sensitivity, as studies have found that the words displayed by wearables are often interpreted emotionally, giving rise to feelings of guilt, shame and anger.

So which elements of the feedback are the biggest offenders?

1) Unproductive

Many high-achievers, taking their sport seriously, have a core belief that productivity is essential to do well. Feedback telling you that a session is ‘unproductive’ is not just harsh but potentially wounding. It can make you feel you are failing, undermining both motivation and confidence.

Kieran File is an associate professor of applied linguistics at Warwick University, and he explains why your wearable might choose the term ‘unproductive’. “It may not be doing anything wrong, technically, but it doesn’t think like a human,” he says. “When we as humans interpret a piece of language, we do so from a really rich, broad context, drawing on information and context that tech doesn’t have.” A ride that was unproductive from a fitness point of view may well have been vital from a mental health perspective.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

2) Performance level drop

As File highlights, in wearable communication the context is missing – without context, data can seem very judgemental. So, you get back in the saddle after a spell off the bike, feel the joy of riding again, but then your wrist vibrates, telling you that you are at ‘Performance level -3’. The watch is simply explaining you have lost some fitness, but if you’ve had a bad day, it can be enough to trigger your mind’s threat system, causing catastrophic thinking and an internal temper tantrum. Not that this is the device’s intention.

As File says: “Your phone or watch doesn’t know you have had a tough day at work or that you have had a fight with a friend, but these things influence the way you process these types of communication. Until the tech can catch up, we need to remember the phone doesn’t have the same schema as us.” If we want to maintain our perspective, we need to roll our eyes and get back to working hard on the efforts that reinstate our lost fitness.

3) Restful

One of the reasons we get annoyed with wearables’ language is that some words have very different meanings in the physiological versus day-to-day senses. Corey Coogan coaches riders in the US but each winter bases herself in Europe to race on the pro cyclo-cross scene. “When I got my watch two years ago, I was mostly alarmed by each new message that came up.” After spending a stressful day white-knuckle driving across the Alps from Italy to Belgium to be told by her watch it had been a ‘restful’ period, she went to Garmin’s website and dug into their formula for creating the outputs. “They are far from transparent regarding their calculations,” she says, “but you can usually get a sense of the inputs. I knew that because I had been sitting all day, my heart rate was low. My watch does not have the ability to monitor HRV [heart rate variability] so it wasn’t in a great position to assess my psychological stress – its ‘helpful message’ was based on daytime HR only, a pretty limited input. Since then, I mostly just laugh at my watch.”

4) Training stress

Another term that has very different physiological and day-to-day definitions is ‘stress’. What stress means in terms of a training tracker may be very different from what stress means to someone handling a difficult period in their life. Your tracker might well give you a ‘Training Stress’ score. Using the word stress to describe this feels misleading because stress has negative connotations and training shouldn’t cause problematic stress for an athlete – many of us ride specifically to relieve and cope better with our day-to-day stress.

When trying to quantify training load, a wearable takes into account external loads (speed, distance, duration) and internal loads (HR, HRV). Some algorithms can also include sleep quantity and quality but none will know your day-to-day stressors from work, relationships, biomechanical or musculoskeletal injuries. These are currently unquantifiable and constantly changing. Professor Neil Walsh of Liverpool John Moores University is clear that “it’s the overall stress that matters to health. Life stress off the bike matters enormously, so it is important to think about that too, not just the training workload which is easier to quantify.”

5) Neutral intent, emotional response

Other words that pop up on our devices may be given with a neutral intent but in a way that can be interpreted emotionally. “For the vast majority of my racing season, I am ‘unproductive’, ‘detraining’, or ‘in recovery’,” says Coogan. “In short, the amount of rest, recovery and tapering that my coach and I have learned is essential for season-long strong performances measures beneath what Garmin advises. Even knowing that we are absolutely in the right – based on actual performances – it can still be hard to see that messaging.” Coogan’s real bugbear is before a race. “If you are rested and very excited, your heart rate should be high. It’s called responsiveness. Essentially, your HR is ready to go. But I get horrible reports when tapering and especially when I hop on my bike for a race day warm-up. I now know, if I see ‘fair’ recovery, I am ready to rock.”

| What it says | What it means | How we might interpret |

| Peaking | Garmin: You are achieving ideal competitive form. Your fitness is increasing despite a recent reduction in overall load. | I’m awesome – bring on the race!… Fine if there’s a race coming up, but possibly unhelpful in a build phase. |

| Unproductive | Garmin: Your fitness appears to be declining but not necessarily because of excessive training loads. If your load focus is optimally balanced, it may be time to evaluate other factors like nutrition, daily stress, and sleep quality | Well, that was clearly a waste of time. Why do I even bother? |

| Recovery | Garmin: Your activities are less challenging than normal and your fitness level is either holding steady or slightly decreasing | Argh! That was supposed to be easy, but it didn’t feel like recovery – I’m clearly really unfit. |

Data can deceive

The biggest problem with following your wearable’s messages is that the data may not be valid or validated. A 2017 study found that over the course of a marathon, where 60,000 steps may be taken, some devices are accurate to within 100 steps whereas others are off by nearly 8,000 steps. A 2018 review of wearables looking at monitoring stress and sleep found only that 5% of technologies had been formally validated. And, when it comes to the algorithms, studies suggest that while some algorithms perform well at the population level, the range of error at the individual level is vast. The implication is, if you rely on messages coming from a wearable to dictate your training or interpret your fitness, you may end up with an inappropriate training load, misguided fuelling and reduced motivation.

Even if the data is accurate, its usefulness to your specific cycling may be limited. “My frustration,” says CW columnist and coach Michael Hutchinson, “is that many devices don’t work that well, with a display based on a really skinny algorithm put together by a coder in California working off a generalised view of activity. They always emphasise volume and calorie burn, and you get little credit for a really good and well-focused interval session.” Conversely, easy riding may be overly rewarded. “Go on a gentle ride with a friend,” continues Hutchinson, “where you don’t ride hard and stop at a cafe, and later you get a fireworks display on your watch face because you have burnt 1,200 calories. Is that really all we’re aiming for?”

Context is everything

Mindful that the language used, and the algorithms creating it, are not truly personalised to your riding or goals, how can we use our wearables to get the most from them? Riders like Coogan and Hutchinson, frustrated by blunt messages from their devices, have delved into the validity of the data. They are clear that no one should rely on their wearable unquestionably, and that relinquishing too much control to an electronic device reduces your ability to tune into your bodily sensations and your self-awareness of your own performance.

Rather than relying on a wearable, it is better to use mixed methods, combining electronic cues with your own self-assessments. Even better is having a coach acting as ‘perspective person’ – not only setting sessions but helping you stay focused on your goals and avoid overdoing it. A coach trained in motivational interviewing uses open?ended questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries. Tech is not yet capable of this type of emotional intelligence. “So often my watch is at odds with what I know to be the case,” adds Hutchinson, “and that’s because I’ve got the experience – I know how it fits together and how individual it is, so I can ignore the damn watch.”

In the same way, Coogan remains hyper-aware of the potential negative impact of clumsy language. “I spend a good deal of time helping my athletes interpret their device message within the greater context. The messages can frankly be triggering and cause stress verging on health anxiety. As a coach, it’s important to dig into the inputs and thus be able to de-escalate the athlete’s alarm.”

What's your type?

If you’re determined to use a wearable, you need to choose one that complements your style, preferences and beliefs, taking into account whether you are motivated externally (chasing goals or places) or internally (chasing the physical feeling). In short, what kind of messaging works for you? “If you want to relate to your wearable as a military drill sergeant,” says File, “then the direct bluntness is coherent. But if you want your tech to be more forgiving and kinder, be aware that you might not get that.”

Before appointing an electronic device to be your trusted advisor, ask yourself some questions. Do you respond best to reward or punishment when training? Do you strive to reach specific goals or ride just for the love of it? Do you like to be told what to do or nudged towards a decision? Once you have answered these questions, you’ll have a better idea which wearable (if any) will provide you with motivation and drive. Next time I’m on a start line, it won’t be my watch I’m looking to for encouragement.

Dr Josephine Perry is a Chartered Sport and Exercise Psychologist whose purpose is to help people discover the metrics which matter most to them so they are able to accomplish more than they had previously believed possible. She integrates expertise in sport psychology and communications to support athletes, stage performers and business leaders to develop the approaches, mental skills and strategies which will help them achieve their ambitions. Josephine has written five books including Performing Under Pressure, The 10 Pillars of Success and I Can: The Teenage Athlete’s Guide to Mental Fitness. For Cycling Weekly she tends to write about the psychological side of training and racing and how to manage mental health issues which may prevent brilliant performance. At last count she owned eight bikes and so is a passionate advocate of the idea that the ideal number of bikes to own is N+1.