What are the differences between ordinary cyclists and someone with the potential to turn pro?

Who hasn’t dreamt of going pro and getting paid to ride bikes. But what does it really take to make that leap?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“Do I have what it takes to become a professional cyclist?” It’s a question that most of us have pondered at some point, at least as a daydream or fleeting fantasy. From having the raw power, to the skill of riding in a bunch at high speeds, to committing to spending a large chunk of practically every day on your bike come rain or shine: there are plenty of factors to consider. But just how far-fetched is this dream? What is the difference between an ordinary cyclist and someone with the potential to take their cycling all the way? In other words, should you quit your job to become a full-time rider? Full-time rider Joe Laverick lays bare the reality behind the fantasy.

“What have I got to lose?” I asked myself when it came to choosing between chasing the pro dream or going to university. With a string of good results in the junior ranks, I knew I’d live to regret it if I didn’t go all-in on cycling. There is a ticking clock on my racing career, whereas I have the rest of my life to get a degree. Still, I knew it was a gamble.

For the sake of this article, we’re going to class Continental level riders as pros. Granted, many Conti riders also work part-time jobs to make ends meet, unable to support themselves solely from the proceeds of racing their bikes. It’s not until you make the ProTeam (formerly ProConti) ranks that a minimum salary comes into play: €27,500 for women and €32,100 for men. I’ve ridden for Continental teams for three years now, and my accumulated earnings don’t amount to a single year’s pay at the above rate. Nobody goes into pro cycling for the money.

At the time of writing, 17,738 Brits hold active race licences (from junior level up), but there are fewer than 150 British professional cyclists – that’s less than 0.85% of licence holders. Based on statistics alone, an amateur racer’s chances of turning pro are less than one in 100. So what does it take? Exceptional power, mental resilience and skill, of course – but that’s not all. In my opinion, the most important factor is a rider’s environment, the conditions that nurture their progress. Having supportive family and friends, enough money and access to opportunities: these elements, often beyond a rider’s control, are make or break. If you’re not dealt the right hand in life, you don’t stand a chance of going pro.

What’s the difference in performance between pro and amateur riders?

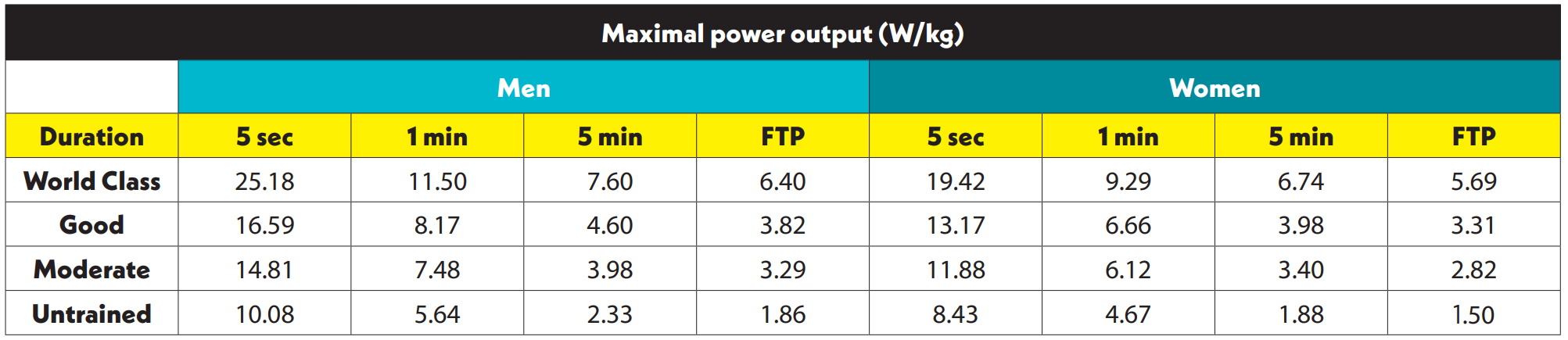

Dr Andrew Coggan’s power profile chart has been around for over a decade and offers an easy way for riders to benchmark their watts per kilogram against expected performance at the various levels of bike racing. Here’s a condensed version…

‘Completely genetic’

While it’s possible to navigate the racing scene without having a family history in the sport, some physical characteristics are non-negotiable. “There are certain beneficial physiological traits that are completely genetic,” says Andy Turner, Cycling Weekly’s resident coach. “Adult lung capacity, for example, cannot be increased, whereas the heart, being a muscle, gets bigger and stronger with training.”

A rider’s potential isn’t always immediately apparent. “You could have two riders starting at the same baseline,” Turner sketches an example. “Rider A is naturally slightly better but Rider B responds better to training. So over time, Rider B becomes the superior athlete.” How long does it take for a rider to truly demonstrate their potential? “After four or five years of consistent, high quality training as an adult,” says Turner, “I would expect a rider to be at around 90% of their capability. The final 10% involves tactics, race experience, fatigue resistance and general fine-tuning.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Most sports scientists agree that a male cyclist needs a VO2max of at least 75ml/kg/min to be competitive at the highest level, and at least 60ml/kg/min for women. This represents the maximum rate of oxygen update, and it is largely genetically determined. The literature indicates that the ceiling on VO2max improvement through training (once moderately well-trained) is around 15%.

There is an element of truth in the phrase “winning the genetic lottery” as applied to the world’s best sportspeople. The extent to which genetics determine sporting ability is not yet known, but estimates suggest that at least 50% of the performance differences between athletes are linked to genes. It’s a harsh reality that, if you want to be a pro, you need the right parents – alas, none of us gets to choose.

Intangible advantages

There are so many intricacies to being a professional racer. Being a generally strong bike rider doesn’t guarantee racing success. Brute strength won’t make up for a lack of tactical nous. Hiding in the wheels, maintaining a good position and moving through the bunch while conserving energy are invaluable skills despite being almost impossible to measure.

Most pros are able to put out crazy power numbers, but very few actually win. The difference is a matrix of choosing the right wheel to follow, making the correct split-second decisions and having the handling skills to put yourself into a race-winning position. The 2016 national road champion Adam Blythe was famously a rider who used race craft and skill to his advantage, always getting himself in the right place at the right time. The winner of a bike race is rarely the strongest, but is often the craftiest.

Pushing the power

The modern world of Zwift racing has taught us that there are plenty of amateur riders who are able to push huge power numbers, sometimes even better (in a controlled environment) than professional road racers – something I learnt the hard way earlier this year when amateur racer Will Lowden beat me in Cycling Weekly’s Club 10 (CW 24 February). But it would be a terrible mistake to quit your job to pursue the dream just because you hit some big numbers on Zwift.

Not all pros are able to produce exceptional numbers in the lab. On a recent episode of ‘The Move’ podcast, Mark Cavendish said: “My power is pretty basic… but there’s a difference between being able to sprint out of the front door in training and sprinting after 200km in a race.” What gives him the winning edge, Cavendish knows, is his race-craft and fatigue resistance.

James Spragg, a performance coach who is completing a PhD investigating fatigue in professional cyclists, believes that, among pro riders, performance capacity when tired is a better indicator of performance than raw power numbers. His research comparing an U23 Continental teams with older professional riders found that, when riders were fresh, performance across the two levels were almost indistinguishable. However, after completing the same tests after multiple hours of riding, the performance of the older pros was more consistent, tailing off less than that of the U23s.

“The ability to continue putting the power out even towards the end of a hard race is now considered a fundamental component of performance in professional cycling.” Spragg says. “There are considerable differences between how much riders fatigue. Having a good sprint is useful, but being able to use that sprint after 200km of racing is what really counts.”

Fatigue resistance goes a long way to explaining what separates winners from journeymen. Of course top WorldTour pros are superior across the board, but it’s their apparent immunity to fatigue that sets them apart. On Stage 11 of the Tour de France, Jonas Vingegaard reportedly pushed 6.1W/kg for 36 minutes on the final climb. As a Continental rider, I couldn’t get close to that, even when completely fresh – Vinggaard did it at altitude after 170km of racing.

Building fatigue resistance often requires long but low-intensity endurance rides – exactly what time-poor amateurs struggle to fit in. The notion that pros simply ride harder than amateurs is only half true. While most pros ride far more hours than you, it is likely that you spend a greater percentage of your training time at a high intensity. Let’s assume the average pro rides 18 hours per week with two intense interval sessions with 30 minutes to one hour of hard effort in each: that’s only eight to 12% of training at high intensity – and even less in the winter.

A typical amateur, on the other hand, squeezes a similar amount of hard effort into far less overall volume. “One of the biggest mistakes amateurs make is going too hard, too often,” says coach Andy Turner. “I spend a lot of my time urging riders to go easier on their endurance rides so as to recover effectively and adapt.”

What it takes

I wanted to speak to amateurs who had actually asked themselves, do I have what it takes to turn pro? Carl Stubbs is a 30-year-old amateur cyclist from Lincoln, racing for his local club Cobl CC. A lifelong sportsman, he first picked up a road bike during the lockdown of 2020, and once racing resumed couldn’t stop winning, quickly gaining his second cat licence. “

“The biggest difference between someone like me and the pros is recovery time,” Stubbs reflects. “I wake up at 5.15am and get a couple of hours of training before work. Then it’s a quick breakfast, shower and straight to work.” There is little time to put his feet up as he goes about his tasks as a warehouse and distribution manager, working eight or nine hours a day. “As a pro, I’d not have that added workload and would be able to focus on recovery.”

Stubbs’s progression has been fast, so does he intend to quit his job to turn pro? “I’m 30 and I’ve got a mortgage, bills and other expenses,” he says. “None of these things would suddenly disappear if I decided to become a pro cyclist, so the answer is no. I’ve come to the sport late, I just want to chuck absolutely everything I can into it over the next few years and see where that gets me.”

Miriam Jessett, on the other hand, very much dreams of going pro. the 23-year old, who is a second-cat racer for Stolen Goat RT, explains: “I was a national level swimmer and after an injury I tried triathlon for a year but decided I like cycling most. Having come to the sport quite late, I feel that I missed out on a lot of the early development stages, especially with bike-handling skills.

What’s her vision for the next five years? “I’m not necessarily expecting to be a full-time racer, as most female pros still have to work part-time but I enjoy racing my bike, and stepping up to the pro ranks comes with greater opportunities – that’s what motivates me.”

Is being a professional cyclist the dream job?

Being paid to race your bike and travel the world sounds like a dream, and in many cases it is. But it’s not as glamorous as it seems; your hobby becoming your full-time job has a heavy psychological impact that must not be underestimated. Once you’re riding for a living, cycling is no longer just your escape, your way to unwind; instead, it is everything, your entire way of life.

The psychological demands are perhaps the biggest difference. For pros, their whole life revolves around the sport and every little detail gets micro-analysed to optimise performance. If a social event is going to have a negative impact on the next day’s training, it has to be sacrificed, as everything must be geared towards long-term performance gains.

Rightly or wrongly, many pros get into the situation where their form on the bike reflects their mood off the bike. It is a very dangerous path to go down, but one that most of us have trodden. With the job description entailing hurting yourself every day, pro cyclists are of course mentally tough, but for most the toughest part is trying to maintain psychological balance, to keep living in the ‘normal’ world.

It is not uncommon to see a promising rider step away from the pro ranks citing a loss of enjoyment or motivation. In 2021, while on Trinity Racing, one of the best development teams in the world, Finley Newmark decided to stop chasing the pro dream. He and I are only a year apart in age, and we raced each other as juniors. When I asked him why he quit, his answer was eye-opening: “The sport did so much for me growing up, gave me a passion, purpose and a community to share that with. But in the last few years, when I asked myself why I was racing, I really couldn’t come up with a great answer.” It seemed to boil down to a question of proportion. “At an early age, I’d taken cycling to an extreme, which over time took the freedom, exploration and community away and replaced it with pressure, sacrifice and an element of selfishness. I’ll always love racing, but I never needed it in such large doses.”

So, should you quit your job and turn pro? Taking the leap

It's never too late to make it to the top, we've spoken to riders who started later in life, yet rose to the highest level, including Australian pro Brodie Chapman, who started racing professionally in 2018, aged 26.

"I quit my job to go pro": Alexander Richardson is a 32-year-old professional cyclist currently racing for Saint Piran. A former oil broker in the shipping industry, he quit his job in his mid-20s to pursue the pro dream and spent two seasons at ProTeam level with Alpecin-Fenix .

“If you want to do it properly, cycling is a full-time job. The second biggest thing for me is psychology. There are enough hours in the day to work and train if you manage them well, but eventually you will burn out.

“Leaving my full-time job, I improved in three parts: my training hours went up, I had better recovery, and it was easier psychologically. There are more hours in the day. A big part of my life is cycling; I might spend four hours a day on the bike, but I’ll then spend a large portion of the remainder thinking and talking about it. You can get pretty good with a full-time job, but you’ll never reach your limit.”

Becoming a professional cyclist is multifaceted, a combination of having the physical ability, the skill, the mindset, the luck and the contacts. If you’re in your 30s or older, I’m sorry to say that unless you have significant financial backing behind you, the train to becoming a professional cyclist has left the station. Much depends on your circumstances: a rider in their teens or early 20s is less likely to have dependents or a mortgage, so why not give it a shot?

Winning races at the higher levels of the amateur scene puts you on the radar of British Continental teams, which in turn will lead to opportunities to show yourself on the bigger stage. But even if you make it onto a Continental team, it’s probably too soon to quit your job. There is a long way to go from domestic success to paying the bills on racing income alone.

Should you quit your job? Not until you’ve signed a ProTeam contract. For me, I’ve been lucky enough to chase the rollercoaster that is the pro dream and it’s the best thing I could have ever done. Whatever the outcome, I’ll always be thankful that I had the opportunity to take the shot.

Joe Laverick is a professional cyclist and freelance writer. Hailing from Grimsby but now living in Girona, Joe swapped his first love of football for two wheels in 2014 – the consequence of which has, he jokes, been spiralling out of control ever since. Proud of never having had a "proper job", Joe is aiming to keep it that way for as long as possible. He is also an unapologetic coffee snob.