Old winter training tricks made new: do they still work?

For pioneering pros of a bygone age, winter was a time to roll out radical new training ideas. Chris Sidwells analyses whether their eye-popping methods still stand up today

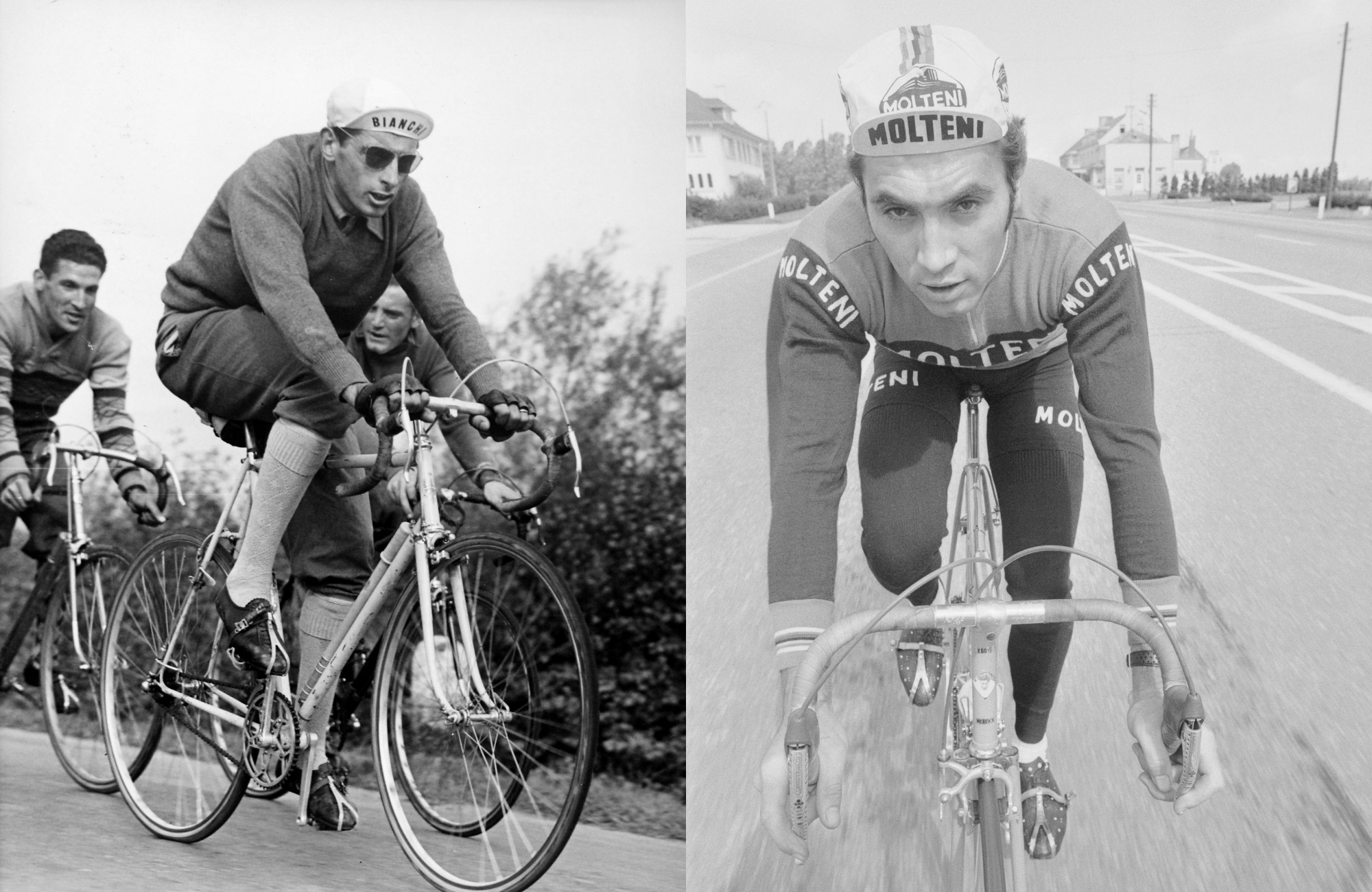

(Getty)

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Modern training is a sophisticated process for world-class cyclists. Peak performance doesn’t just happen, it takes planning, built on a firm foundation of knowledge. Winter is a key part of that plan. Before the end of each road season, team training staff are planning for the next, and first up is how each rider will make the best use of winter. But it’s not always been like that.

Until quite recently, even big teams and successful cycling nations left riders to themselves for the winter, not coming back together until the pre-season training camps. The rationale was that they were professionals – cycling was their job, so they were expected to know how to prepare for the following season and come out of winter in good condition. And do you know what? Some of them were very good at it.

Most would follow a generic training plan, largely continuing with what they did as amateurs, but with more miles – because they were pros now, it was their job. A select few did things differently.

The very best riders in each generation thought about their sport and how to prepare optimally. They analysed the demands of cycling, the muscles used and processes involved in performance, and they came up with their own ideas for how to make sure their winter training sowed the seeds of summer success.

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

In this piece, I’m going to recount some winter training protocols of bygone stars – not their whole programmes, of course, just some specific methods they used in winter – and I’m going to ask current experts for their assessment. How effective were these methods, and how can they be brought up to date with modern equivalents? My first example goes back to the 1940s and 1950s, to a training method used by one of the all-time greats of the sport.

Method 1 - Fausto Coppi’s weighted waistcoat

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The principle: Like many pro cyclists of his generation, Coppi – the first rider to win the Giro d’Italia and Tour de France in the same year, which he achieved twice – loved hunting. It was an activity pro riders only had time to do in the winter; it kept them active while relaxing and socialising, often with team sponsors. Coppi, though, saw it as a chance to build his muscles.

He hunted in the hilly woods of Piedmont, north-west Italy, tramping up and down steep slopes all day long, and it struck him how similar walking uphill was to pedalling. That got him thinking: what if he made walking uphill a bit harder? It would load his leg muscles and cardiovascular system in a similar way to cycling – in a way he’d be training.

Coppi asked the person who made all his cycling clothes, Vittoria Gianni (whose business ultimately became Castelli) to make him a hunting waistcoat. It had pockets for cartridges, food and other supplies, but the waistcoat was lined front and back with long, slim pockets for custom metal plates – it was effectively a weighted vest.

Did it work? I need properly qualified help to judge the effectiveness of these old winter training methods, so I’ve turned to a world-renowned cycling health and performance innovator. Phil Burt has worked with the best: he was head physiotherapist with British Cycling for 12 years, and consultant physio with Team Sky for five years.

“It was good thinking by Coppi,” Burt tells me. “He made an everyday activity harder, taxing his muscles, so it became a strength-and-conditioning exercise. Even today, a lot of WorldTour teams don’t pay enough attention to strength and conditioning, and they are missing a trick, because it benefits endurance cyclists in many ways. Strength and conditioning helps them become more robust, helps keep them aligned, which helps prevent injury. It can also boost performance.

“Bradley Wiggins took strength and conditioning seriously. When he decided to target the 2014 time trial world title, he took on a complete strength-and-conditioning programme during the winter, having a gym just like the one at BC headquarters installed in his home. One of the exercises he did was high-repetition single-leg presses, which is a bit like what Coppi was doing by walking uphill in his weighted waistcoat.

“I’m sure that the extra strength Brad built helped him beat Tony Martin, who was a beast in a time trial at that time. He’d won the world title three times in a row before Brad beat him in 2014, then Martin won again in 2016.”

Modern equivalent: Coppi’s idea was solid, but we don’t expect you to start walking up and down hills wearing a weighted vest. A strength-and-conditioning programme with qualified guidance is well worth considering, though. Burt says: “It helps widen the foundation, the base of the pyramid of fitness and form, and you can’t build a tall pyramid without a wide base. Strength and conditioning also helps to prevent injuries, and makes a more robust athlete.”

Vuelta a España 2020 stage winner and third overall Hugh Carthy was in the middle of his winter training while I wrote this. He’s doing a full strength-and-conditioning programme in the gym, and I asked him why. “To prevent injury really, and help keep me aligned and have a solid core. Strength training with weights is also very good for bone health, which can be badly affected if you just ride a bike all the time,” said Carthy.

Method 2 - Adding weight to your bike

The principle: This is a classic, and something cyclists have done for years: training on a heavier winter bike, or even adding extra weight to it. Until the late 1960s, almost every club cyclist’s winter bike had a thick canvas saddlebag, mostly the iconic Carradice longflap. Some legendary hardmen and women carried bricks in them, and two more recent champions took adding extra weight to extremes.

In their early days, before any Olympic success, aspiring sprinters Sir Chris Hoy and Craig MacLean competed to see who had the heaviest winter training bike. “Craig won,” Hoy says. “He filled the frame tubes with lead shot, and put weight-lifting plates in the bike’s pannier bags. It weighed more than 40kg.”

Did it work? Phil Burt reckons so: “Adding weight to the bike you train on increases the training load, and since your body responds positively to load, it gets stronger and fitter. It’s as though your body thinks, ‘Oh, that was heavy or hard, I’d better make myself stronger.’

“Making things harder in training is effective. I remember Jo Rowsell saying to me that people kept telling her that her road bike position wasn’t very aero. So I asked her, why did she want it to be aero as a track pursuiter training on the road? Her pursuit position had to be aero for performance, but she’d get more training effect from her road rides if she wasn’t aero.”

Modern equivalent: Using a heavier bike to train on, compared to your race bike, is a sound idea. It’s practical, too; heavier tyres are generally less prone to punctures, and heavier bike equipment is less prone to wear. It’s also cheaper to replace. And a heavier bike increases the training effect of any session, so your body increases its response and builds back fitter and stronger.

There’s also a psychological boost to be had, one that British Cycling uses a lot, as Hoy explains. “Other nations often remarked on how British riders stepped up at each Olympic Games. One reason was we had people working to create the optimal bikes and clothing for each Olympics, but we waited until the Games to bring the whole package out in one go. Our rivals would use any new piece of kit as soon as it was designed, incrementally improving over the four-year cycle, but not feeling the full benefit when it mattered most.

“Taking the gains in one go was a huge mental boost. When I won world titles with fairly standard equipment and clothing, it gave me confidence knowing there was more to come. It was something you looked forward to through the long hours, days and months of training between Olympics. Then when we got all the new stuff right before going into action, it felt incredible. I often wonder how much the improvements were actually down to the kit as against the psychological boost.”

Gaining a mental as well as a physical advantage by saving your best kit for racing is something everybody can do. Riding a great bike with all the performance and aerodynamic bells and whistles is a fantastic feeling, but when preparing for races, there is a competitive advantage to be had by training with heavier, less aero kit.

Method 3 - Over-geared uphill intervals

The principle: One of the training sessions that young Chris Hoy and Craig MacLean did on their super-heavy bikes was, says Hoy: “a resistance training session out near Edinburgh Airport. We’d ride up this hill in an incredibly high gear, even applying the brakes to make it harder, then ride back down and keep going up and down. We must have looked comical putting maximum effort into riding so slowly, but we believed it was cycling-specific resistance training.” Hoy and MacLean were using an extreme version of over-geared uphill intervals, a method cyclists have used for years.

One of the earliest examples I know of is the 1970s Belgian Classics hardman Frans Verbeek. Coincidentally, it was Verbeek who changed the way professional road racers trained in the winter. Before his time, it was common for even the best to not touch their bikes in November, and do just the occasional ride in December. Some rode winter six-day races, so had to keep trim for that, but it wasn’t unusual to begin on 1 January with only a few miles in their legs and some extra padding around their middle. Verbeek thought he’d steal a march by training earlier.

“It was Eddy Merckx who made me think about extra winter training really,” Verbeek tells me. “The 1970s were the easiest time to race, but hardest to win. The only tactic was follow Eddy Merckx and try to hang on when he attacked.

He was that good, and I was that realistic, but I still wanted to beat him, so I thought if I couldn’t out-class Merckx, I’d out-train him.

“I rested up for two weeks after my last race in October, and started riding every day from 1 November, rain or shine, wind or snow. I didn’t just do long, steady rides either, I did what I called power training sessions. Once a week, I took an old bike I had with a single gear and rode it to a forest. There was a long, straight climb with a sandy surface, and I rode up it pedalling really slowly because it was steep, but giving it everything. I think the first time I tried, I didn’t get to the top, the gear was too high. But I kept on trying and adding repetitions, and I got stronger. By the end of the winter, I went up it 50 times in one go.”

Did it work? Phil Burt says: “Pedalling slowly but pushing as hard as you can recruits a lot of muscle fibres, which is one of the principles of lifting weights. You could argue that lifting weights is more effective, because there are two contractions for each lift – the concentric contraction in which muscles shorten for the lift phase, and an eccentric contraction in which muscles lengthen in the down phase. The eccentric contraction recruits more muscle

fibres than the concentric, but when pedalling, you are mostly only getting concentric contractions.

“Over-gear pedalling is still effective training, though. And it is specific to cycling, so you get the benefit of specificity. Specificity is one of the keys to improving in a sport. You don’t become a better cyclist by running a lot.”

Modern equivalent: Over-gear uphill efforts are a valid training method now. Many pros do long climbs, alternating sections of over-geared riding with high-revving efforts. A turbo session with

two or three 15-minute threshold or sweet-spot intervals, each broken into five minutes at normal revs, five minutes in a high gear at low revs (about 50 to 60rpm), and five minutes at normal revs is very effective.

Method 4 - Riding a fixed-gear bike

The principle: Many old pros did this. Jacques Anquetil would ride the first two or three weeks of his winter training on a bike with a low fixed-gear, or by racing in six-day races on the track. Old pros thought that riding or racing on a low fixed-gear – for six-day races, it was usually 52x16, which at race speeds meant fast pedalling – helped them rediscover or hone what the pros back then called ‘coup de pédale’.

Did it work? What they were describing was their feel for the pedals, the way muscles and limbs coordinate to create the greatest force at the pedals from each calorie of effort put in. They were talking about efficiency. You can have the biggest VO2 max known to human performance, but if you don’t pedal efficiently, it won’t be as effective as it could be in producing power at the pedals.

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

“Pedalling a low fixed-gear definitely improves pedalling technique, which improves efficiency,” says Phil Burt. “It works different muscles, too, so it’s good for all-round development.”

Modern equivalent: Most top British road racers now have track experience, many excelling at the discipline, some even having won Olympic and world championship titles – and that’s because British Cycling performance coaches appreciate the crossover from track to road racing. During his time as head coach, Shane Sutton said: “If somebody can produce 560 watts in a team pursuit while whacking round a huge gear at 132rpm, then if they lose weight, they are going to go up mountains fast.” Most aspiring road racers would benefit from some track racing or training each winter.

Method 5 - Riding on loose surfaces

The principle: Another great Belgian Classics rider, Freddy Maertens – who co-holds the record for most stage wins in one Tour de France, with eight – used to ride through the sand dunes. “I did it with friend and team-mate Michel Pollentier,” he tells me. “On long road rides, we often did the middle two hours in the dunes, pushing as hard as we could. You had to, it was the only way to make progress through the deep sand. It made us strong.”

Did it work? “It would force more muscle contraction, which creates a bigger stimulus for the body to respond to by getting stronger to deal with it, so yes it worked,” says Phil Burt. There’s also scientific evidence that riding on loose surfaces improves pedalling efficiency.

Modern equivalent: Include a bit of off-road riding in your winter training. Not only does it help make you stronger and more efficient, it will improve your reflexes and bike-handling, and it’s great fun. Enjoy!

Fixed in their ways - Reg’s revenge

Reg Harris is a British cycling legend, an Olympic medallist and was track sprint world champion four times during the 1940s and 1950s. His advice on fitness sold periodicals all over the world.

Harris’s golden training rule, one he imparted to all who wanted to emulate his feats on the velodromes of Europe, was: “Ride fixed. An 80-mile bike ride is more enjoyable, but that’s not how you build strength and speed. You do that by slogging up hills, and spinning down on a heavy fixed-gear bike.”

It remained his golden rule until one day when he was out training with Trevor Fenwick. “Reg trained alone a lot,” Fenwick told me, “but he liked group rides and Sunday club runs…. One day, I was on my road bike, and as always, we were sprinting for all the village signs. Reg usually won, but he didn’t that day because my road bike had a bigger top gear…. The next week he came out on his road bike and hammered me in every sprint. That’s why he was a world champion, I suppose – he hated losing.”

Winter wackiness - Boardman’s soggy spirit-sapper

“Include the craziest winter training idea you’ve ever heard of,” suggested CW’s fitness editor when he commissioned this piece. But there were too many to choose from! Epic rides, pro cyclists wearing weighted diver’s belts, others running around sand dunes carrying their wives on their backs – yes, that one happened, thanks Mr and Mrs Maertens. So instead, I’ve chosen a source you wouldn’t associate with craziness: Mr Planning and Preparation himself, Chris Boardman.

“One winter, after I turned pro, I started doing back-to-back eight-hour rides,” Boardman told me.

“I hated them, they were mind- and spirit-numbing, so I turned some of them into adventures and rode to new places, meeting my wife in a hotel at the end.

“One ride I did went from the Wirral into Lancashire, over the Nick O’Pendle, and onto North Yorkshire, so right across the north of England. Thing is, it rained all day, there was a headwind all the way, and because there was no such thing as GPS devices, all I had was notes on a scrap of paper. The notes got soggy and ripped, I got lost and it took so long that it was dark by the time I got there. It was horrible.”

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast