Racing is not training

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We probably all know someone who doesn't subscribe to training. Instead, they simply ride their bike in-between riding races. The extreme case study that comes to mind is one local time triallist who would ride a club 10 on a Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday - and then an open race at the weekend.

Sunday was the club run, so all his weekly training was taken care of! Friday was his only concession to rest and recovery. This is extreme, but it's not uncommon for cyclists to be racing three or four times a week in the summer.

There's nothing wrong with racing this amount in itself, indeed this is at the very heart of some people's enjoyment of the sport. However, if the reason for participating in the sport is for the cyclist to see improvements in performance, racing at this frequency isn't going to cut it. After all, racing is not training - it's very different.

I'd like to explain why and also to help cyclists think about how to nudge up their race performance using a carefully designed progression of training stress.

Underlying principles

The physiological systems (such as the heart and lungs, muscles, energy use and metabolism) are finely tuned to meet demands: and these systems are very ‘plastic' structures that when strained and stressed will change.

With no strain or stress, the body will stay where it is. If demands go up, with a short period of recovery, the body will rebuild to be stronger in order to prepare itself for another bout of stress. This is the bottom line of something we call ‘adaptation to training'.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Through repeated cycles of stress and recovery (the training plan) the body and its systems will break down (because of the training session) and re-build (during periods of recovery) to a new higher level (training adaptation). A coach can plan the rate of progression of this training stress - the amount of stress placed on the cyclist, and how quickly that amount of training can be ramped up week on week.

The variables the coach must manipulate to place the ideal amount of stress on the athlete are the so-called principles of training: specificity, overload, recovery, progression and reversibility.

Keeping it specific

As a coach, it's my responsibility to tie my athletes down to a race season plan. However, even when I think we have a finalised plan, I often have to deal with a few challenging curve balls when an athlete informs me of a few last minute race entries.

Why do I cringe when I find myself in this situation? Surely, if the aim is to get fit, racing can only help get you into shape? To some extent, this is true. Undoubtedly, there are some benefits that racing brings to race form.

You may have come across the phrase ‘race yourself fit' (normally being bandied around by the old-school cycling fraternity). I doubt racing achieves this, but it does help you become more race pace-efficient. Riding in the race position, at race powers, at race cadences will get your body more ‘practised' at that movement, and more efficient.

Being more efficient means using less oxygen per watt, so for the same absolute fitness (oxygen uptake) you can push more watts and go faster. Indeed, in a research study we performed in a group of French pro cyclists, we observed improved performance that was directly related to the time spent racing, all explained by increased levels of efficiency.

Likewise, the importance of efficiency is seen to come in to play in time trial specialists, in particular. It's very common to see a drop off in an athlete's power output as they shift from road bike to race bike riding at the beginning of the season. Going back to the principles of training mentioned earlier, racing scores highly on the specificity scale.

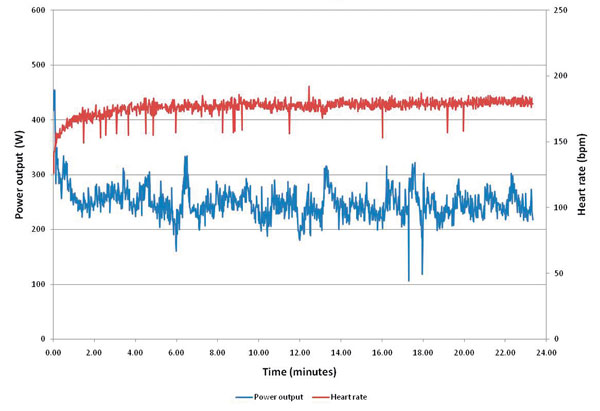

But, let's get to the heart of the matter: why racing isn't the same as training. Let's consider a time triallist who wishes to raise their race power from 250 to 270W. Each time they race a 10-mile time trial, they race at maximum effort, and the result is 250W [see graph, above]. No matter how often they keep racing, all they can do is give their maximum effort. Over time, they will see an improvement, but that's purely down to the improved efficiency mentioned earlier. This progress is likely to be very slow and ultimately very limited as they haven't improved fitness, only efficiency.

Don't forget the overload

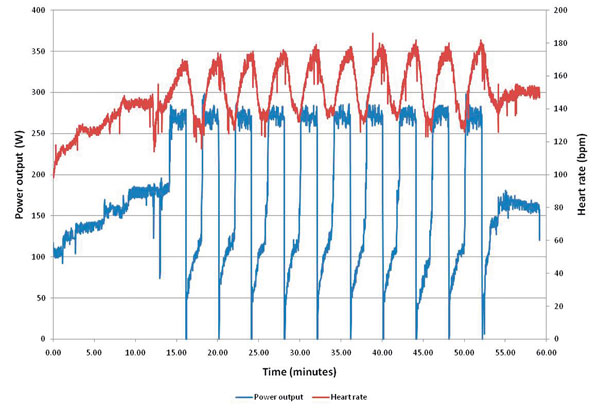

If instead they train at the weekend, there's the opportunity for them to ride above their current maximum race power [see graph, right]. The rider can perform race target intervals, where the aim is to reach 270W for 10 miles TT power. The training sequence starts with 10x2 minutes at 270W (20 minutes, similar to race time), with equal recovery.

The following week, it might be 10x2 minutes, but with half the recovery (1 minute). Then, we might decrease the recovery further or increase the time of the rep to 3 minutes (i.e. 7x3 minutes). Getting the rider to work at 270W for blocks of time, they can ride above their current tolerable maximum and this is the key to enhancing training stress and allowing overload - another of the principles of training.

Overload is planned by a coach using a combination of the intensity of the training session, and/or the frequency of the training sessions in the week, resulting in a change in the overall training volume (frequency x session duration).

Crucially, racing doesn't allow for overload. Intensity-wise, you can only ride at your maximum; frequency-wise, you're limited by the amount of recovery needed between going all out in each race effort. Overall volume is capped by what's tolerable without extreme fatigue: the few race efforts, while high intensity, are relatively short in duration.

Perhaps a clearer way of presenting this is to calculate the total work done across a race at 250W for 23 minutes and a training session incorporating 5x5 minute blocks at 270W: the former gives 345kJ, the latter 405kJ.

The breaking down of the effort into blocks allows more work to be done, but also to make it at the intensity at which the body needs to become accustomed to. This latter point is key - take a similar training session I like to call ‘redline' (three-minute blocks above and below a sustainable power), which we use to encourage the body to get better at clearing lactic acid.

An athlete using this session pushes their body's physiology to greater extremes in the three minutes above the sustainable power than they might hold in an hour-long race. In the race, you sit at your maximal lactate steady state, so you don't ask the body to clear lactic acid at the same rate as in the redline session. As a result, your maximum race effort isn't as demanding as a well-planned training session.

Work hard, rest hard

We have all experienced how much racing to our maximum takes out of our bodies. Racing does drain our systems dry. An hour of hard racing will nearly deplete our stores of muscle glycogen, the bodily stores of carbohydrate.

Even with a diet high in carbohydrate, it will take 48 hours to fully rebuild stores; and re-fuelling is only scratching the surface in terms of how long recovery takes post exhaustive exercise.

Many other systems are stressed by high-intensity exercise with muscle damage and immune system suppression among them. Yes, these systems are also suppressed by hard training, but in a more planned, predictable and ‘safe' way. Races take longer to recover from than training. Without sufficient recovery (principle #3), we won't get training adaptation. Racing ourselves fit becomes racing ourselves tired.

Over-racing will lead to severe fatigue and stale performances. An overtrained athlete would need two weeks of complete rest to even enable training to begin again (and often a season can be written off).

Plan for progress

Earlier, we explained how a series of intervals at a target race power enables a solid build in training demand to be planned. Structuring a series of sessions in this way enables the principle of progression to be ticked off the list.

Normally, we would advocate a build in training stress of around 5 per cent per week - whether that's volume, intensity or frequency. It's far more objective giving an athlete numbers to build with (270W intervals building in duration, or number; or decreased recovery between the repetitions) than expecting a similar improvement in race performance week on week.

Remember, in racing you go all-out: the only progression is trying to go faster and harder each week. I don't know of any athletes who have successfully applied that in a season.

Of course, there are other obvious benefits to including some racing in your training plan. For a start, there's the mental aspect - going through race preparation, staying focused - these things all need implementing in the overall plan.

Equally, psyching yourself up for an event too much can have a detrimental effect on your race performance. There may also be specific aspects of performance to practise: following a pacing strategy for example; or getting familiar with the sports nutrition plan you and your coach wish to use.

There's also familiarity of effort that needs to be learnt (or remembered from the previous season). Before national championships, for example, I advocate three practice races at the distance of the key event - so a rider with two goals of races over 10 and 25 miles might do six races in the two months prior. That's still a race every other weekend, opening up one weekend to perform some focused training. Ultimately, it's all about finding a balance, and this is something for the athlete to explore.

Making yourself racing fit

Decide what you want from your training schedule and stick to it. Sit down and really consider what you want from your cycling: consistent year-round performance or fewer, bigger peaks. Neither is right or wrong: just be honest with the consequences of your choice.

Choose two or three events that will allow you to practise performance in your chosen goal and use these to perfect your race preparation, pacing and nutrition strategies. Make sure you race no more than every other weekend, thereby giving you one weekend to devote to training and achieving that ‘beyond maximum' approach to performance development.

If you are struggling to hit training targets due to lifestyle or work commitments, leaving you with not enough time to carry out your workouts or creating tiredness, consider dropping your race at the weekend to prioritise the training. Doing so will take you further in the long run.

Maximum Lactate Steady State (MLSS)

MLSS is about maintaining an only-just manageable amount of lactate in the body.

When you start producing lactic acid, it's like turning on a tap.

The bath (your body) can only hold so much to stop it overflowing, so you need to drain a little water away by turning off the tap and recovering.

Once the level has dropped, you can open up the tap again to refill it.

Training allows us to keep the level in balance by increasing the energy production by opening the tap while draining away the consequences of the metabolic waste.

This article was first published in the Autumn 2011 issue of Cycling Fitness. You can also read our magazines on Zinio, download from the Apple store and also through Kindle Fire.

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.