How to train harder: Three gluttons for suffering reveal how they do it

If you want to take your fitness to the next level, the simple truth is, you’re going to need to train longer and more intensely — that is, harder

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As Greg LeMond said, “It doesn’t get easier, you just get faster.” We all know cycling is a sport that favours those capable and willing to put themselves through epic amounts of physical punishment — in training as well as racing. Whether it’s extending the weekend long ride, setting the alarm for an extra session before work, or stepping up the intensity of intervals, cycling encourages and rewards stubbornness and a certain degree of self-torture.

Let’s face it, most of us have wiggle room to train at least a little harder and endure a shade more discomfort. So let’s learn from the specialists how to make even bigger sacrifices and dig even deeper — for the sake of big gains, and without losing perspective or enjoyment. We speak to three real-world riders known for their relentless work ethic, canny ability to avoid burnout and insatiable appetite for pain…

No one goes deeper

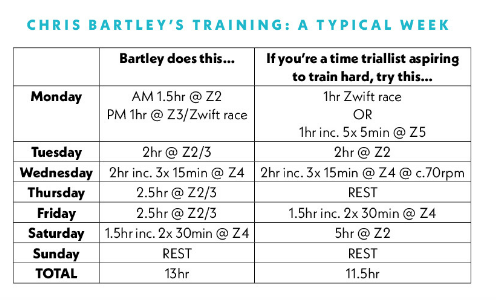

Rower turned TT ace Chris Bartley

Chris Bartley is an ex-Olympic rower turned full-time rowing coach and time triallist. Having learnt how to punish himself through years of rowing in the British Rowing Academy, the 35-year-old has transferred that understanding of how to suffer from the boat to the bike. In 2018, he placed second in the National 25 and 50-mile time trials, beaten only by Marcin Bialoblocki — a man who spent six years as a professional rider.

Bartley doesn’t train huge hours, but when he does train, he makes it count. Once he’s made sure the steady ‘base’ miles are done, he goes deep, very deep. His ability to squeeze every last watt out of himself comes from an intimate understanding of his body and its capabilities.

“If I know something is going to be particularly hard, I make sure I’m ready, physically and mentally. If I feel like I’m not going to get the best out of myself, I move the session to another day. I’m not a full-time rider and so I need to make the most of every session.”

By doing those all-important intervals when he knows he’s capable of absolutely smashing them, Bartley trains his mind for racing success. “Nailing those really hard sessions builds confidence. It teaches me to be bold when going into races; I know that when I’m rested and ready, I can physically and psychologically tolerate the hurt it requires to achieve what I set out to do.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Central to Bartley’s hitting the numbers is not pressurising himself unduly. “If I don’t want to train because I’m not feeling motivated or am generally tired, I won’t. I know that I can’t perform when I feel like that. Knowing myself and not feeling obliged to train is a good way of preventing overtraining.”

He uses his experience to time his sessions to perfection. “Sometimes you have to rein yourself in; if you smash a really hard session one day, you can be encouraged to try something hard again the next day, but that never works. You need to let that top-end system recover before you try to access it again. It’s

about understanding your body and your limits.”

To train that intensely, you need to know that you can’t do it too often. Even in a peak week, Bartley only does two or three hard sessions.

Being very internally motivated, Bartley relishes racing himself — he finds beating his own bests just as satisfying as winning races. When building for a key race, he sets intermediate goals, so as to enable him to compete with himself.

“I try to beat power PBs from a similar time last year, or use Strava times on segments relevant to my races,” he says.

Coach Trevor Connor says: “Overall, he’s ticking the right boxes for a time triallist, with a focus on threshold power. I would try to include some low-cadence work in the threshold sessions, which a lot of time triallists favour as it builds strength and torque. Even though Chris’s races are all under an hour, a lot of benefit would be gained from one longer endurance ride, so I would add that too.”

Make the time!

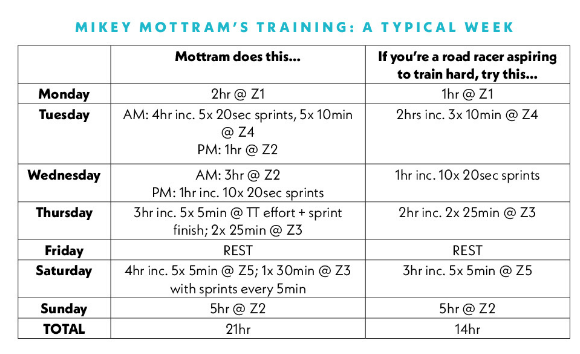

Road racer Mikey Mottram

Mikey Mottram is a 28-year-old road racer in his first season of racing for UCI Continental team Vitus Pro Cycling. The step up from amateur ranks is a fitting reward for his years of training 20-25 hours a week while holding down a full-time job managing his family's commercial flooring business.

To follow Mottram on Strava is to feel perpetually lazy - he has usually completed a four-hour session by 9am, whether it's the depths of winter or the peak of summer. And the same goes for non-race weekends, only the rides are longer then.

Mottram clocks up a colossal 440 miles in an average week, many of which are ridden before most of us have hit snooze on the alarm - serious motivation. His mental ability to manage fatigue - combined with a burning desire to improve himself - has made his routine feel relatively normal.

"I was a national-level rower until 2013, and to some extent felt unfinished with the sport, like I had more to give. I started cycling for something to do rather than to be 'good' or achieve at a certain level, and that's still the main thing motivating me - it's about achieving my full potential as an athlete."

Although Mottram's dedication to his huge training load never seems to waver, he's not claiming it's always easy. Being married to Caragh McMurtry, who's a full-time national rower, is essential to maintaining his drive.

"Seeing her pushing to succeed keeps me motivated to keep pushing myself," he says. "I'm not sure I could handle these early starts if she wasn't doing it as well; we get up together and go out training at the same time - it's like any other couple going out to the office at 8am."

Training for 25 hours a week alongside a 30-35 hour job could push a rider perilously close to burnout, if not well monitored and managed.

With support from his nearest and dearest, Mottram understands what it is to be training hard and how to spot signs of overtraining.

"I keep a close eye on what my body's telling me, but sometimes my wife needs to step in and tell me to rest as well."

Now he has stepped up a level to race at UCI Continental level, Mottram knows his training needs to step up too.

A full-time job leaves no time for extra volume, so it's now about really nailing the intensity. "Most of my rides include intervals, so I'm trying to really focus on the quality and make every session count," he says.

As well as knowing when to rest, Mottram is very careful to look after himself off the bike: "I ensure I eat healthily, and do regular stretching, mobility and core work - I manage to get most of this done while I'm waiting for my dinner to cook," he explains.

Coach Trevor Connor says: "This is totally appropriate for Mikey. A less accomplished riders should be mindful of trying to replicate this, though, as it's real tough! A novice or intermediate racer would want to keep similar intervals but drop the volume. The mix of threshold and sprint work is great race-specifity."

Work, rest, play...work some more!

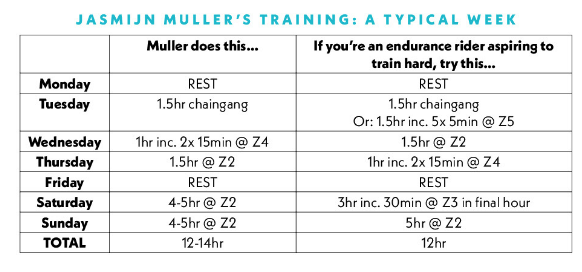

Endurance champion Jasmijn Muller

Jasmijn Muller, 39, is the 2017 world 24-hour time trial champion and Zwift distance record holder (1,828km in 62 hours). As well as being a full-time management consultant working 40-plus hours a week, including frequent travel, she somehow finds time to train har and smart enough to achieve world-class results.

To progress her fitness, Muller focuses on her weaknesses rather than simply training her strengths.

"I have a good endurance base as it is, and I don't need to do much to maintain that. Instead, I do a lot of higher-intensity trainer rides in the week, and these pull my overall fitness up. The longest ride I'll do at the weekend is only around six hours - any longer than that and your risk not recovering properly and jeopardising future weeks of training."

Despite the time pressures, Muller knows that sometimes she has to go long.

"Every now and then, I do a really long ride where I test how my mind and body react to being in the saddle for a long time, how to deal with sleep deprivation, and check my nutrition strategy. I do one really long 'test' ride a month, building the distance each time - typically and Audax."

Muller's races are all about testing limits but she knows that training effort must not be forced or priorities skewed.

"For me, dealing with fatigue from lost sleep with work is always going to be one of my biggest obstacles. Sometimes I have to just accept I cannot do something and cancel an event - you have to appreciate that rest is an important part of training." Her ability to say no is key to staying healthy in the long run, and not missing large blocks of training as a result of pushing too hard at the wrong times - training hard requires you to understand 'sensibly hard'.

"My partner does a lot to minimise my life stresses, and enables me to focus on training. However, while he supports me when it counts, he doesn't over-indulge my hobby and keeps me sensible about my training and events. If you get too immersed in your sport it can become destructive."

Coach Trevor Connor says: "This is a great plan for endurance, and the addition of some intensity from the chaingang is key to pushing up the threshold. A good way to boost endurance when time is limited is to throw in some sweetspot or tempo work towards the end of a longer workout - something Jasmijn could try if she's especially short on time.