Turn your fears into a fearsome cycling performance

Facing up to her pre-race nerves, Michelle Arthurs-Brennan discovers that confronting fears head-on can help you ride faster

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nerves are not the enemy. Most of us who’ve competed in challenging events are familiar with the following: butterflies, lost appetite, sweaty palms and even uncontrollable trembles. Fear is natural — it’s what we do with it that matters, because whatever scares us also has the capacity to make us faster.

There was a time when my mind would invent phantom injuries in the lead-up to races, which would miraculously disappear as soon as the start line came into view. I’d spend all week struggling with incessant knee pain, only to realise there was nothing wrong with my body that adrenaline couldn’t magic away as soon as the starter horn went.

Those nerves became even more pronounced when I entered the Good Friday track meet at the end of March — my first time racing on an indoor velodrome in front of an actual crowd. This time there were no phantom injuries, just a vague feeling of nausea. Turns out, that’s normal too.

“You need the adrenaline and the excitement to access the best physical performance,” says Chris Hoy, who tells me that the way he dealt with nerves changed dramatically over his career — which included, let’s remember, 11 world titles and six Olympic golds.

Hoy worked with Professor Steve Peters, the psychiatrist famous for writing The Chimp Paradox whose techniques he used to harness the power of his nerves.

“Every time [you race] you get nervous because it’s a necessary part. If you’re too relaxed, you’re not mentally switched on,” says Hoy.

“There’s a difference between being adrenalised and being anxious. You can plot the graph of alertness; at a certain point it tips into anxiousness and performance drops off a cliff.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Finding the perfect point on that graph, just the right level of nerves, might come down to language choices. “Never use the words nervous or anxious; use the words exciting and adrenalised. It’s a physiological part of responding to something that’s going to be exciting. Regard these feelings as a good thing.”

Nerves vary between individuals and situations, Hoy acknowledges, but he believes everyone can make use of them.

Spectator-phobia

“What if I let them down?”

For me, anticipating having an audience opened up the fear floodgates. I’m used to racing; I’ve got to a point where I can deal with the butterflies and the phantom injuries. But racing in front of spectators, including friends and family, and possibly letting them down? Petrifying.

That is, until I actually did it. As soon as the first race kicked off, I had tunnel vision — all I focused on was what was going on around me. When I did acknowledge the crowd and heard their cheering, they were transfigured from being ‘a group of people potentially about to watch me fail’ to ‘a group of supporters encouraging me to succeed’.

The key trigger here is a fear of not meeting expectations. Katie Page, a sports psychologist who coaches athletes at Mind Training for Sport, points out that the pressure is almost always internal.

“So much of this is connected to pressure, or perception of pressure,” says Page. “It’s fascinating — there’s often a lightbulb moment when the athlete realises, ‘I’m pretty much the one creating the pressure.’”

How to bring about this lightbulb switch in perspective?

“Remember it’s your choice that you’re doing that event. You can look at it with fear and dread, or as an exciting thing, an opportunity. Learn to be your best coach by providing positive and constructive self-talk — your language is important.”

If it’s other people creating the pressure, bear in mind that it’s probably not their intention.

“You need to discuss it with them,” says Page, “and advise them what they can do to help. Maybe they’re saying you need to get a certain time, and they believe they’re helping you, but unless you communicate back that it’s not [helpful], they won’t know. It may be more helpful that they remind you of techniques you’ve practised before a race.”

The Big One

“What if the occasion overwhelms me?”

Even Chris Hoy has let nerves get in the way. Having become kilo world champion in 2002, 2003 was a nervy year.

“I was last to go in the World Championships in 2003,” he recalls, “and I reacted to what was going on around me. I was looking at my rivals, saw how fast they were going, and so changed my approach based on other people. I went out way too hard to chase the time I thought I needed, and in reality it was a quick track and a quick day. I got fourth and I was devastated.”

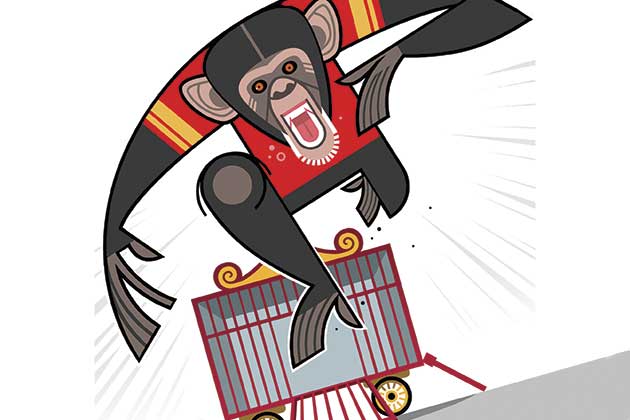

Working with Professor Peters helped Hoy to avoid repeating his mistake. Peters’ Chimp Paradox theory, in short, is a mind management tool that encourages people to “cage the chimp” — control the part of the brain that works with feelings instead of logic.

“If you start having negative thoughts, with the chimp coming out, [you imagine] all sorts of negative scenarios: what if I lose, he’s looking fast, I don’t know if I can beat this guy. It’s about reminding yourself to bring it back to the things you can control.”

Take the pressure off yourself, Hoy advises, by focusing on the performance, not the longed-for result.

Fearing the worst

“What if I crash again?”

Thom Dean found himself in a high-dependency unit after a crash while racing at Derby velodrome in 2017. He suffered multiple breaks and doctors treating him considered his condition to be critical. The RAF officer pulled through and was treated by Air Force medics. Once able to resume riding, he had to accept fear would be unavoidable at times. Seeing beyond fear required continual use of visualisation techniques.

“I spent time beforehand thinking about what it would feel like to first ride and then race in a bunch again. I thought carefully not just about the emotions but als o the physical sensations I would experience, so that when it came to it, I wouldn’t be surprised by my reaction.”

Dean was rebuilding confidence when a wobble from two riders in front brought the fears flooding back. “I was spooked, to the extent that I dropped off the back and pulled out of the race,” he recalls.

Returning home after serving in Afghanistan, he underwent training designed to help handle post-conflict fear. “We were told never to feel silly if a passing car, sudden noise or similar caused us to flinch or drop to the floor in those first weeks after coming home. Rather, we were to think of those events as reflecting the instinct that kept us safe out there, and to be grateful that our bodies were ready to look after us.”

These techniques proved useful in overcoming his fear of crashing: “It helped me to understand that my sudden unexpected fear [on the track] was not just natural, but actually helpful in the right circumstances. I just had to rewire my response to make sure it didn’t distract me.”

Dean’s coach advised him occupy his mind with objectives and tasks.

“He might ask me to ride on all four corners of the bunch during a race, or to pick out another rider to deliberately follow their moves. Having these tasks occupies the part of my mind that would otherwise be worrying, and allows me to achieve a goal while my ability to compete at the very sharp end recovers.”

>>> Can you buy your way to a fitter you?

The military man has gained a new respect for nerves as a physical response that fulfils an important role and which can, to some extent, be tamed.

“I’ve learned to listen to my body and to recognise and respect nerves for what they are — a sixth sense that is useful but which sometimes needs to be retuned to fit the actual risk I’m taking. Recognising, accepting and replacing the unwanted thoughts and feelings has been key.”

Chronic nerves

“I just can’t stop worrying”

I get most nervous for the National Championships or for an event where there are good weather conditions, as I want to make the most of the opportunity in each situation,” says 2017 British Best All Rounder Alice Lethbridge. “I am nervous before every race, in fact, because I always want to do well.”

Success has not proved an antidote to nerves for the multiple record holder.

“I tend to struggle to sleep for two to three days leading up to a big race and always the night before. If it’s a really important event, I struggle to eat the day before. I am sometimes visibly trembling on a start line and have to focus on deep breathing to calm myself down.”

In June last year, Lethbridge broke the 100-mile competition record on the E2/100, on which she says: “I realised that the record was a possibility very early on and I became very nervously excited because that was something I’d always dreamed about being able to do. I started being sick about 10 miles in, though, probably due to the nerves. I was anxious until I crossed the finish line.”

>>> 11 of the best fitness upgrades you should try

Lethbridge has learned to cope with her nerves “only through following a lot of superstitious routines that help me to keep calm.” These superstitions include “lucky pink socks” of which there are two pairs — though “one pair is luckier than the other, and I have to think carefully about which way round I use them if I’m racing on consecutive days.”

Her eating routine is also quirkily regulated: “I always have to have a weird [combination of] Weetabix and other bits mixed together as my pre-race meal, plus a piece of fruitcake from my mum.”

Unfamiliar territory

“What if I’m caught by surprise?”

Ian Robertson started riding sportives eight years ago and has now made the move into Audaxes. He recently completed the 400km from London to Wales and back. In covering such distances, there many logistical considerations and much that can go wrong.

“I get worried the bike will break down, that I’ll get stuck in the middle of the countryside, unable to get back, that I’ll get lost,” he says. “I don’t worry about not being able to complete it anymore; I know I can do that. It’s more [fearing] matters outside of my control.”

Robertson has a method of dealing with these worries: “I list, mentally, all the things that could go wrong and find solutions. Where is the nearest town? The nearest railway station? I know what the ride will be like, what to expect on each stage, where the next big climb is, when to plan the next stop.”

Dr Katie Page has additional advice for those who are worried about new terrain and new courses: “Look for pictures of that location and familiarise yourself [through visualisation]. Create a routine — this could include what you do when you arrive, how you warm up, what you eat before a race, then use it every time.”

Facing my fears

Everyone gets nervous. Suggesting that nerves need to be squashed or minimised doesn’t help us — it’s far more constructive to control them and harness their power.

Entering the Good Friday track meet was a reminder to me of what it feels like to be extremely nervous — perhaps a jolt into the realisation that nerves are an important part of competition. The moment we stop feeling nervous, something has gone wrong.

The reality was, as soon as the racing kicked off, my mind focused on the wheel in front, the lapboard and finding gaps in the bunch — there was no room for nerves, which receded far from my mind. The sound of cheering from the stalls complemented the whole experience, and during the most intense periods of racing, I barely noticed it.

>>> What can cyclists learn from other sports?

Going into the event, my aspirations didn’t extend far beyond staying upright. I’d expected a split in the field and to find myself in the lower echelons of proceedings. As it turned out, though the top three spots went to GB development riders Ellie Russell, Abbie Dentus and Lauren Dolan, and though I was hanging on more than punching for points, I was able to stick with the pace — and nerves did not for a moment hold me back.

This is typically the case: fears quickly ebb away once the event kicks off, morphing into forward propulsion and energy, with little conscious effort.

Calm your inner chimp

Psychologist Dr Anna Waters is part of Steve Peters’ Chimp Management team. She uses the ‘Chimp Paradox’ model to explain what gives rise to pre-race nerves.

- The Chimp Paradox model breaks the brain into three themes: the human part, which is rational and logical; the primitive chimp, which is designed to keep you safe and perpetuate the species; and the computer, which is where beliefs and memories are stored, as well as automatic, learned programmes.

- Messages get sent to your chimp first — because the chimp’s main agenda is your safety and security. When the chimp feels like you’re under threat — it could be you’re on the starting line of a race, or having to do a presentation at work — that part of the brain goes into the flight, flight or freeze response, which triggers the sympathetic nervous system, then you release noradrenalin and adrenaline, causing the symptoms of nervousness.

- It’s those hormones going round your body that cause you to sweat, get heart palpitations — what your body is doing is getting ready for a fight or flight situation, so it’s sending blood flow to the muscles to be ready.

- Your chimp looks into the computer, to see how it should respond — the computer could contain helpful beliefs, unhelpful beliefs, or a prompt to go to autopilot. So if we’ve learned to believe “I always get nervous” — and stored that in the computer — the chimp will panic, even becoming nervous about being nervous.

- Throughout that whole process, the human part of your brain doesn’t get a chance to intervene. Unless you look into your computer, and address those negative beliefs, the chimp is always going to get nervous before events.

- It’s just a case of picking up these thoughts and deliberately changing them — write them down, look for patterns. When you understand what it is specifically that the chimp is worried about, then you can work through an action plan for coping with that.

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.