A rider's paradise: Why the Dolomites are still the best place to ride your bike

The famous mountain range has some of the best climbs in the world. Adam Becket goes in search of one of the hardest.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At dusk and dawn, if you’re lucky, in the Dolomites you can experience a phenomenon that’s unique. As the light is in its in-between period, passing through its liminal space from day to night, the mountains start to glow a pink-red colour. The phenomenon, which has its own name - enrosadira - is one of the many things that are special about this part of the world.

The mountains here feel different from anywhere else. They’re jagged and pointy, screaming out into the air. You both do and don’t have time to contemplate the majesty around you as you cycle through this landscape; a part of the world less than three hours from Venice but as isolated as it is possible to be in the centre of Europe. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but unlike my closest one at home - Bath - it is fully based on the beauty of the natural landscape.

I came to the very northeast of Italy, the land of that not-often spoken dialect Ladin, in search of some of the toughest but dreamiest roads to cycle on, to grind my way up. Trust me, there was a lot of grinding to be done. The Giro d’Italia often passes through this way in its reliably brutal final week, but while the names might be recognisable - Gardena, Sella, Pordoi or Giau - these are further down the bucket list than the more easily reachable French Alps or the Pyrenees.

It might be in Italy, in Veneto, in fact, but everything has a very Austrian vibe here, with its sloped roofs and Gothic churches. One half expects someone in lederhosen to appear, but this is Italy, one part of the patchwork country. Italian is spoken, but so is Ladin, and so is German. The Dolomites are a world between worlds.

Alta Badia, in the western Dolomites, is a playground for those in search of passes to tackle on two wheels. When I visit in high summer the region is so verdant that it is hard to think of it carpeted in snow, but the ski lifts and cable cars are present as a reminder that this is as much a place for people who like throwing themselves down the climbs with planks of wood attached to their feet as those who like tackling them in reverse.

In Summer, though, the bike is king. You want to go out early - the weather is nothing if not consistent in my time in the Dolomites, with a beautiful first part of the day giving way to a thunderstorm over the second part. If you are an early riser, this should suit you well, but everyone should remember how quickly the weather can turn.

I find myself in Corvara in Badia, surrounded by the Sella group range in the Dolomites, to ride both the Sellaronda Bike Day, and some of the roads used in the Maratona dles Dolomites, both of which happen in June and July every year. The former is a closed-road celebration of cycling, with the passes around the Sella group closed to motor traffic for a whole day, while the latter is one of the tougher gran fondo events in the world, with 4,230m of climbing over 138km.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

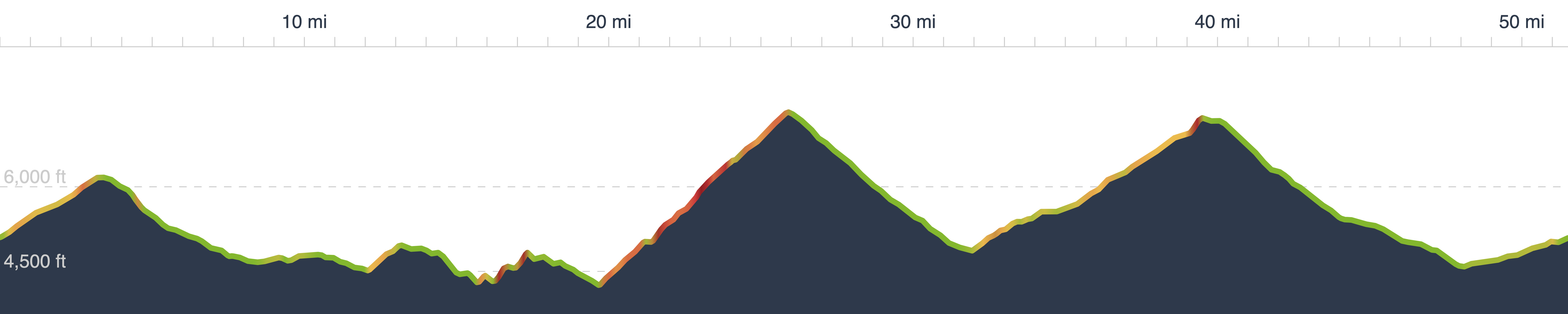

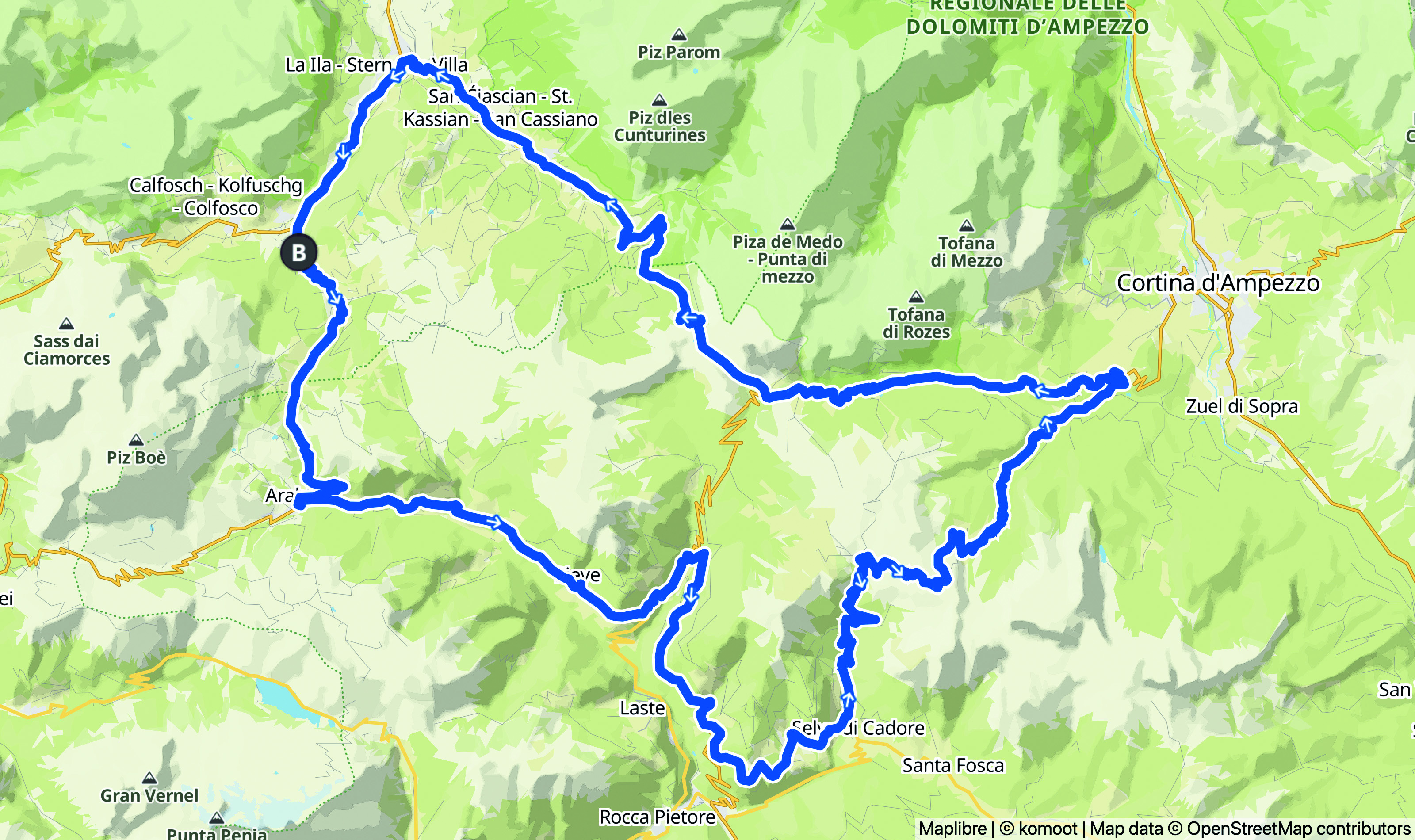

To my gratitude, I am not riding the full Maratona route, with its frankly murderous profile, but just a part of it. Sunday’s ride takes in the Campolongo, the Valparola and the Giau, ably guided by Tommaso Cominetti, a Ladin local keen to show off his magnificent back garden. It follows the Bike Day on the Saturday, where I climb the Campolongo, Sella, Pordoi and Gardena in just over 50km, an amuse bouche to the meal that is Sunday’s ride.

Stellar ronda

On Saturday, the Gardena is first out of Corvara, 8.34km at 6.8%, which is a nice wakeup, but nothing too much. The thousands of other cyclists on the road help motivate me to push up the pass. There are a couple of ramps, but it is manageable; the following Sella is much the same, a bit shorter than the Gardena but more or less the same gradient. Nothing terrifying. The views, though, are magnificent, both of the nearby Piz Boë, and the further Dolomites.

We tackle the Pordoi on its slightly less attractive side, thanks to the anticlockwise nature of the Sellaronda Bike Day, and so we have the ignominy of descending down the prettier side, the eastern, which is worth knowing. The Campolongo, 3.84km at 7.1% is a short punchy end to the day, but that was just the warm up ride.

Reader, I admit, I was nervous before Sunday. I may have performed ably on the previous day, comfortably managing the four passes without too much of a struggle, but this ride is a different beast. The one that looms large in my head is the Passo Giau, a mythical climb which terrifies me: 9.47km at an average of 9.5%. Tommaso tries to comfort me by pointing out that I was fine on the climbs the day before, but this is unavoidably a whole new test.

The route is simple enough: 84km with 2,468m of elevation, from Corvara back to Corvara, with three classified climbs on the route. The climbing begins as soon as we leave the hotel, straight onto the Passo Campolongo. Fortunately, this is the smallest of the day’s climbs, and the perfect opportunity to wake up your legs. 5km at 5.6% is practically easy, right? The smooth tarmac on the first twisty part, with 13 hairpins, is thanks to the Giro d’Italia peloton passing through here on stage 18 earlier this year, and is very welcome. On that day, Santiago Buitrago joined the break on the climb, and went on to win the day at Tre Cime di Lavaredo, on the other side of Cortina d’Ampezzo.

The other side of the Campolongo is more difficult, but that is merely forgotten about as this is the bit we descend next, taking the final corners down into Arabba at pace. The skill of taking hairpins at full speed might still eludes me, but this is by far and away the quickest part of the day, the lull before the storm that is to come. Traffic is light, with many cyclists still out here from the Bike Day the day before.

The next part of the ride is as rolling as it gets for the whole day, skirting the edging of some of the biggest mountains, avoiding the Falzarego pass on the way to tackle the Giau. There are glimpses of the Marmolada, last used in the 1989 Giro, through the mist, and any time the road bends and you get a look at the valley beyond, it is jaw dropping. It is moments like this that the bicycle is truly king, because it allows you to see sights like this at a pace which allows you to appreciate them, something that could not be done in a car. Way down in the valley, you can see the Lago d’Alleghe, and the beginning of the Piave river, through the rock.

In Summer, though, the bike is king. You want to go out early - the weather is nothing if not consistent in my time in the Dolomites, with a beautiful first part of the day giving way to a thunderstorm over the second part. If you are an early riser, this should suit you well, but everyone should remember how quickly the weather can turn.

I find myself in Corvara in Badia, surrounded by the Sella group range in the Dolomites, to ride both the Sellaronda Bike Day, and some of the roads used in the Maratona dles Dolomites, both of which happen in June and July every year. The former is a closed-road celebration of cycling, with the passes around the Sella group closed to motor traffic for a whole day, while the latter is one of the tougher gran fondo events in the world, with 4,230m of climbing over 138km.

To my gratitude, I am not riding the full Maratona route, with its frankly murderous profile, but just a part of it. Sunday’s ride takes in the Campolongo, the Valparola and the Giau, ably guided by Tommaso Cominetti, a Ladin local keen to show off his magnificent back garden. It follows the Bike Day on the Saturday, where I climb the Campolongo, Sella, Pordoi and Gardena in just over 50km, an amuse bouche to the meal that is Sunday’s ride.

Giau for now

Onto the Giau. It starts suddenly, at a T-junction, a road that just heads up into the hills. At the bottom here I’m at 1,336m above sea level; by the top, 90 minutes later, I will be at 2,226m. It quickly becomes apparent that while it is hard, it is not the climb that I had built it up to be in my head. Sure, I am not going particularly fast up the 10% slopes, but I’m still moving forwards. This is a climb without ramps, really. It just keeps going and going, for almost 10km.

There are moments of complete serenity of the Giau, as we climb higher into the mist, the only sounds are those of nature and my heavy breathing. Quite often, however, the peace is broken by motorbikes, those that have come down from Germany or up from Italy just to use the same road we are on. I begrudge their superior horsepower. Tommaso tells me of his wish that they were banned from the UNESCO site, and I’m inclined to agree, especially as they belch fumes in my face.

In Summer, though, the bike is king. You want to go out early - the weather is nothing if not consistent in my time in the Dolomites, with a beautiful first part of the day giving way to a thunderstorm over the second part. If you are an early riser, this should suit you well, but everyone should remember how quickly the weather can turn.

I find myself in Corvara in Badia, surrounded by the Sella group range in the Dolomites, to ride both the Sellaronda Bike Day, and some of the roads used in the Maratona dles Dolomites, both of which happen in June and July every year. The former is a closed-road celebration of cycling, with the passes around the Sella group closed to motor traffic for a whole day, while the latter is one of the tougher gran fondo events in the world, with 4,230m of climbing over 138km.

To my gratitude, I am not riding the full Maratona route, with its frankly murderous profile, but just a part of it. Sunday’s ride takes in the Campolongo, the Valparola and the Giau, ably guided by Tommaso Cominetti, a Ladin local keen to show off his magnificent back garden. It follows the Bike Day on the Saturday, where I climb the Campolongo, Sella, Pordoi and Gardena in just over 50km, an amuse bouche to the meal that is Sunday’s ride.

Sky's the limit

As we hit the slopes I’m at my limit, because although the Valparola is a lot more gentle than the Giau - 11.35km at 5.7% - it has started to rain and I’m tired, cold, and hungry. I’m assured there will be food at the top of the climb, but that seems like a very long way away. The beauty of the last climb is not quite replicated here, with the road hemmed in by trees and the skies darkening.

The road over the pass was built in the First World War to bring supplies to the front line, and while this might not be the battlefields we in the UK think of when it comes to the Great War, the battles fought in the Dolomites were among the most brutal and deadly. Italian and Austro-Hungarian forces fought themselves to a stalemate in the mountains. The signs of battle are still around, not least in the fact that there is a hole in the top of the Col di Lana, which was blown up by the Italians to prevent a route being used by the Austro-Hungarians.

In Summer, though, the bike is king. You want to go out early - the weather is nothing if not consistent in my time in the Dolomites, with a beautiful first part of the day giving way to a thunderstorm over the second part. If you are an early riser, this should suit you well, but everyone should remember how quickly the weather can turn.

I find myself in Corvara in Badia, surrounded by the Sella group range in the Dolomites, to ride both the Sellaronda Bike Day, and some of the roads used in the Maratona dles Dolomites, both of which happen in June and July every year. The former is a closed-road celebration of cycling, with the passes around the Sella group closed to motor traffic for a whole day, while the latter is one of the tougher gran fondo events in the world, with 4,230m of climbing over 138km.

To my gratitude, I am not riding the full Maratona route, with its frankly murderous profile, but just a part of it. Sunday’s ride takes in the Campolongo, the Valparola and the Giau, ably guided by Tommaso Cominetti, a Ladin local keen to show off his magnificent back garden. It follows the Bike Day on the Saturday, where I climb the Campolongo, Sella, Pordoi and Gardena in just over 50km, an amuse bouche to the meal that is Sunday’s ride.

Key info

Distance: 84km

Climbing: 2,468m

Max gradient: 21.3%

Where to eat

Any of the villages the route passes through have shops, cafes, and bars open. If you want proper food, Cortina d’Ampezzo is not too far off the route. I had traditional Ladin food - some kind of rosti - at the Rifugio Passo Valparola, where a main meal will set you back about €10.

Where to stay

Corvara in Badia is a great hub for accommodation, as are any of the towns in Alta Badia. All the climbs are accessible by bike. I stayed at the Hotel Marmolada, where a single night sets you back €300.

Local bike shops

Corvara in Badia has multiple sports shops that offer bike hire in the summer months, when they’re pretending they are not ski shops. Pinarellos can be hired from Sport Kostner Rent from €65 a day.

Adam is Cycling Weekly’s news editor – his greatest love is road racing but as long as he is cycling, he's happy. Before joining CW in 2021 he spent two years writing for Procycling. He's usually out and about on the roads of Bristol and its surrounds.

Before cycling took over his professional life, he covered ecclesiastical matters at the world’s largest Anglican newspaper and politics at Business Insider. Don't ask how that is related to riding bikes.