Icons of cycling: Stayer bikes

Stayer racing is one of the fastest ever forms of motor pacing

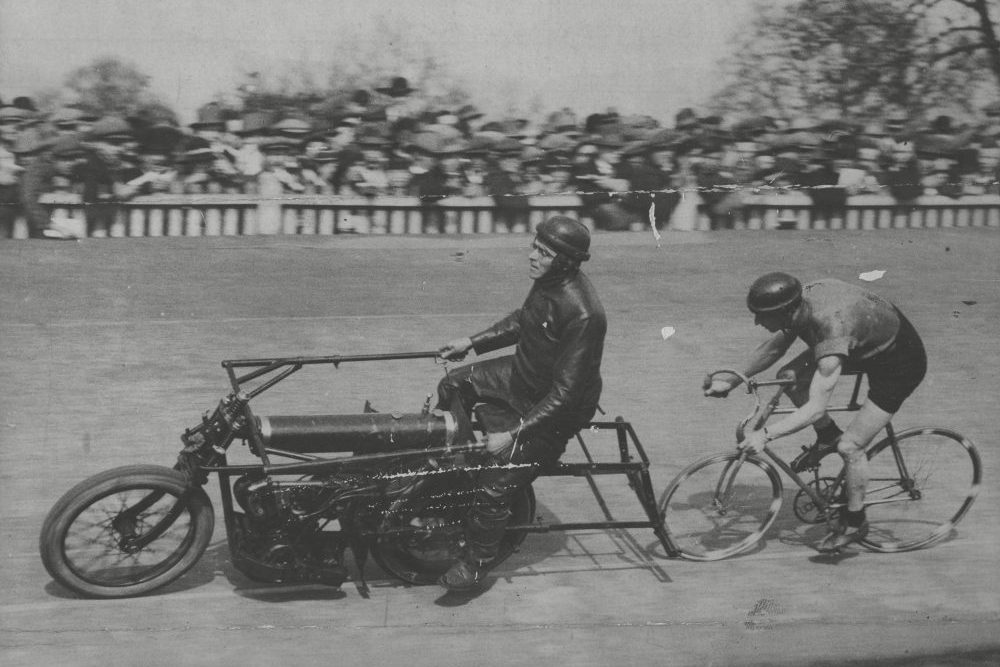

A motor-paced race at Herne Hill velodrome (Credit: ANL/REX/Shutterstock)

Stayer or motor-paced racing is a special branch of cycling that once filled huge stadiums and had its own world title.

There are still stayer races and, like all branches of cycling, stayer bikes have developed — with disc wheels replacing spokes, for example — but the demands the bikes meet, and adaptations made to do so, haven’t changed much in well over 100 years.

Stayers are paced by powerful motorbikes. Speeds are high and races take place in velodromes, so the forces the bikes and riders endure are much bigger than in any other cycling discipline.

Stayer bikes are constructed not only to meet those demands, but to also take as much advantage of the shelter the pacing motorbikes give within the rules of competition, which are very strict.

>>> ‘Motorpaced peloton’ catches breakaway close to finish as complaints over drafting continue

If they weren’t strict then riders could reach speeds that exceeded safety limits. In fact, in the early days of stayer racing, before the rules were developed, serious injuries and even deaths weren't uncommon.

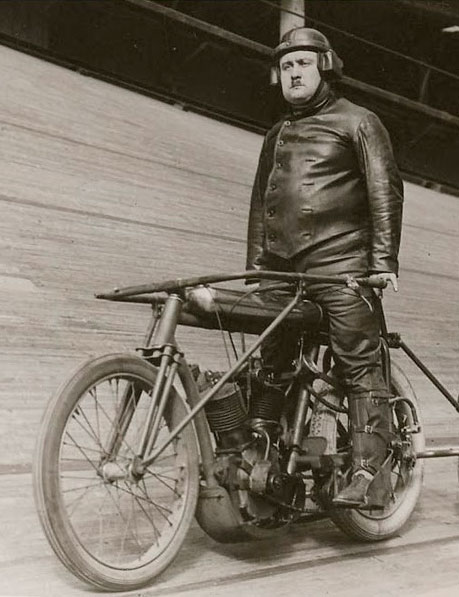

Let’s start with the major adaptations. The rear wheel of a stayer bike is standard size, but the front is much smaller at 24 inches, and the fork blades are reversed.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

This is so the rider and bike can get as close to the pace bike as possible, although an adjustable roller attached to the rear of the motorbike keeps the gap between pacer and rider at a safe distance, reducing speeds to a safe level.

Unusual construction

In the heyday of stayer racing frames were made from heavy-gauge steel tubes.

>>> Bowman Cycles releases first ‘ultra modern’ steel frame

They had twin-plated fork crowns and sometimes other forms of extra bracing to keep the frame as rigid as possible.

Saddles had extra support at the nose by way of an adjustable rod that bolted to the nose at one end, and to either the top tube or to a plate welded to it.

It’s against the rules for the saddle nose to extend in front of the bottom bracket so, although this isn’t allowed now, riders adapted their saddles to make them shorter and sit slightly closer to their pacers.

Handlebars also got extra support from another steel rod that extended from the fork crown to the stem clamp bolt.

Chainrings were massive — 60 plus teeth was common, with 67s used on smooth outdoor tracks.

Stayer chainrings also had reinforced shoulders to prevent flex because distortion could derail the chain, usually ending in a high-speed disaster.

Watch now: Tubular vs Clinchers vs Tubeless - which is faster?

There are more but the last major adaptation is how the tyres were fixed on stayer bikes.

The tyres were special, always tubulars and not only stuck to the rims by very strong adhesive, but often secured by weaving a continuous shellac-soaked cotton ribbon from the sidewall of the tyre, diagonally across the rim to the other sidewall, then back again until the entire tubular was covered.

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast