Racing on a budget vs no expense spared - here's the difference money made to my cycling performance

Just how much faster could an average rider go if they had access to all the best aerodynamic kit and knowledge? Cycling Weekly Editor, Simon Richardson went to find out...

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last year I set out on a project to get more aerodynamic on the bike on the cheap. With an old frame, some borrowed equipment and a couple of items of test kit, I built a time trial (TT) bike and adjusted my position to get as aerodynamic as possible. The whole setup cost less than £200 and led to a significant improvement over previous TT times set on a standard drop barred road bike.

This year the natural progression was to see if and how I could take it to the next level. To find even more cycling speed. With a better position and better kit would the improvements continue in a linear fashion and see me post ever faster times? That was the hope. But little did I know things were about to get complicated.

First up, the kit. This was in fact the easy part. I knew Specialized had a Shiv in my size that was gathering dust in a pro rider’s garage, and a loan of a bike that is known to test exceptionally well in all scenarios was the perfect start. I’d kit it out with a SRAM Red Etap AXS one-by groupset and there’d be no stopping me.

Building the bike was relatively simple, even the oft troublesome internal routing for the disc brakes was straightforward. The Etap bar buttons were easy to locate and feed through to the brain sitting under the steam, while the wireless blips can go almost anywhere. Wireless setups, where you’re able to place gear-change buttons exactly where your hands sit, are perfect for TT bikes for which holding a set position is everything.

The bike that editor Simon Richardson was hoping would carry him to ever faster times

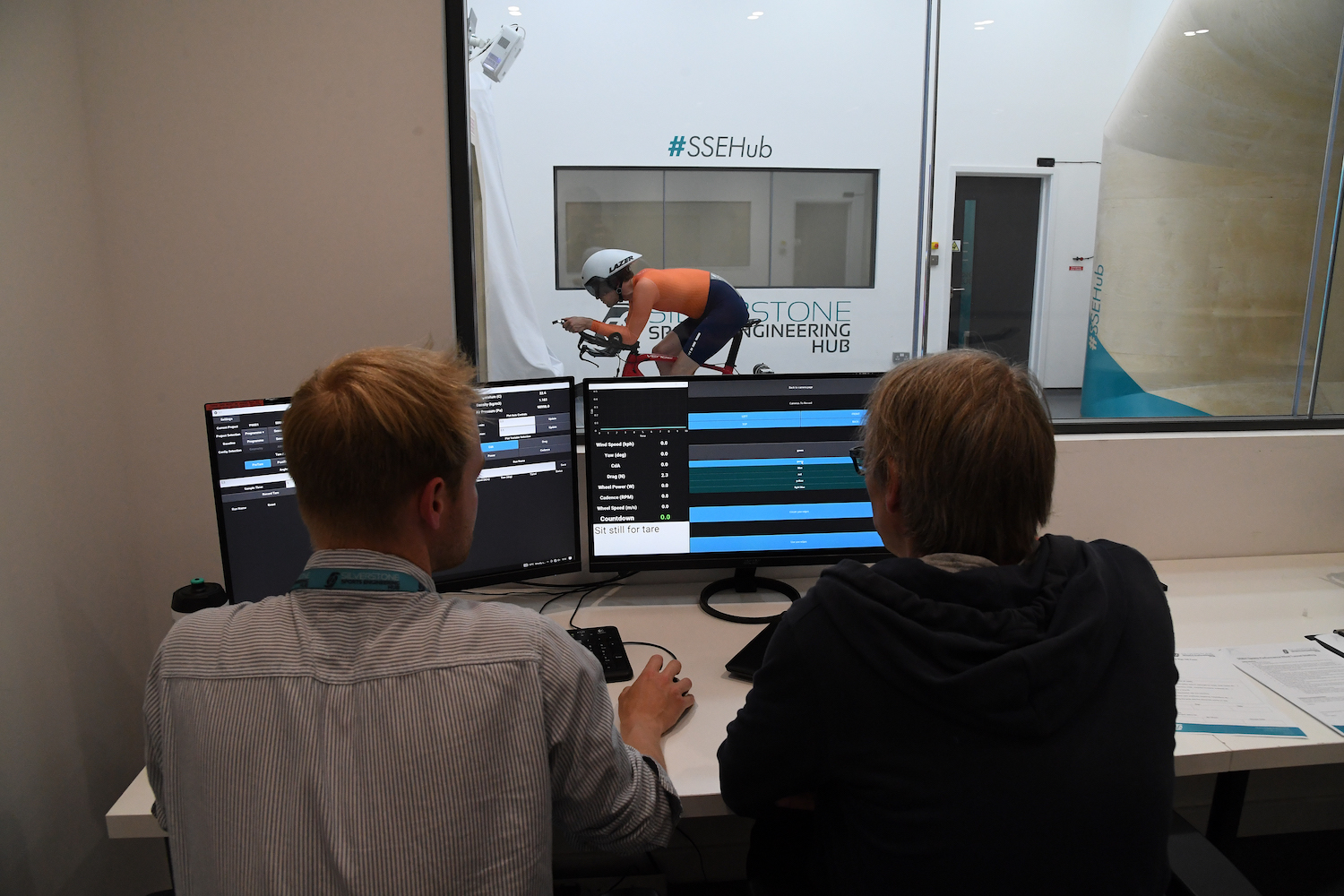

With the bike ready to roll I drove up to the Silverstone Sports Engineering (SSE) windtunnel. With two bikes and test kit I was excited to see how many watts the £10k+ SRAM equipped Shiv would save over an eight year old, converted £1,600 road bike. With three hours of tunnel time to play with we’d then get my position dialled in to perfection, save even more watts, and I’d come away from the whole experience ready to race.

Because that’s how it works, right? Well, not quite. Welcome to the aerodynamics rabbit hole.

The options are endless once you're in the windtunnel, even with two experts at your disposal

I’ve had more conversations regarding aerodynamics than I care to mention. And most of them with the man stood behind the screen to my left, pushing the buttons and telling me when to pedal. Dr Hutch is well known for his riding exploits and column in CW magazine, but he’s also an aerodynamic consultant, currently working with the Irish team, and I’m constantly picking his brains on the subject.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I’ve been lucky enough to watch Chris Boardman at work in a windtunnel and have had my brain frazzled by Tony Purnell, once of Jaguar F1, now with British Cycling, on the theory behind it all.

I know you have to get your frontal area as small as possible. That some kit works for some riders’ positions and not others, and that a change in position can throw out all previously gathered data forcing you to start all over again. But even this knowledge is barely scratching the surface and I’d never had the chance to try it myself. Now was that chance.

We started by measuring my position and kit from last year, choosing to blast air at me at 45kph at a five degree angle (most testing is done at yaw angles between 0-10 deg, as it’s more representative of real life riding conditions - you’re rarely riding into a dead-on headwind) while I’m pedalling at 100 watts, the software then calculates how many watts I’d have to ride to sustain that speed. We’d also capture my CdA (coefficient of drag) for each test. The aim for that number is to get it as low as possible.

A side by side comparison of my position on the Venge and the Shiv

The headline from the table is that with the new kit and a few positional tweaks we managed to find 31 watts from last year's setup. We tried some other kit including a Rule 28 skinsuit and its ribbed undervest - one watt quicker than the Castelli suit, Rule 28 overshoes - lost that one watt again, and a POC helmet - similar savings to the Castelli setup but I couldn’t see where I was going.

With each ‘run’ requiring the wind tunnel to be fired up and reach its speed, a ‘tare’ taken to establish a zero point, then a 30 second measurement was taken, we rattled through our three hours in no time. Due to me forgetting the extensive box of nuts, bolts and spacers that allow for the armrests and extensions to be adjusted to multiple heights, we had barely scratched the surface of positional adjustments for my elbows and hands. A key factor in finding the optimal TT position.

My forgetfulness turned out to be a blessing as fiddling with the bar's intricate fixings would have taken up most of our time, and those three hours had flown by as it was.

The idea of coming away with my perfect position was so far from the truth it was laughable. That perfection is like the horizon, something you can chase but never quite reach. There is always something else to try. In an ideal world I’d have gone back to the tunnel with one set of preferred kit for a session dedicated to getting the extensions in an optimal position. A quick fingered mechanic would help with that.

But we had to settle with what we had. The new position with the HJC helmet in either the Castelli or Rapha skinsuit would be how I tackle the remaining races of the season.

All I now had to concentrate on was recreating this position on the road, sustain 245 watts, and 45kph was achievable. That’s a 53 minute 25, or a 21 minute ten. But this is where things got difficult. In the tunnel I had a live display of me riding projected onto the floor in front of me.

| Run description | CdA(m2) | Power at 45kph | Change from baseline |

| 2021 setup (Venge) | 0.231 | 277 | 0 |

| Shiv with HJC helmet | 0.224 | 266 | -11w |

| Saddle down 15mm | 0.22 | 260 | -17w |

| Bar pads down 10mm | 0.219 | 259 | -18w |

| Bar pads inwards | 0.214 | 253 | -24w |

| Head lower | 0.212 | 250 | -27w |

| Castelli suit | 0.21 | 247 | -30w |

| Rapha suit | 0.205 | 245 | -31w |

On top of that was a green outline of my last, or a preferred, riding position. Moulding myself into the green outline was easy. I had a direct visual cue and didn’t have to worry about staying upright (the bike is held up by stanchions in the floor) or looking where I was going.

On the road, none of those things apply.

This was immediately brought home to me when someone took a pic of me in a TT where I looked more like a meerkat on the lookout than a streamlined, 45kph tester.

Getting my head down, whilst being able to look a safe distance up the road, was perhaps the biggest challenge. And without my green outline projected onto the tarmac in front of me I had no idea if I was keeping my CdA at 0.205 and therefore banking those precious watt savings.

I spent as much time as I could in the position, going on the sensations in my shoulders and neck as I tried to replicate the wind tunnel position, but this was only possible in races and during turbo sessions. The Shiv’s setup was not appropriate for training rides.

An array of info is displayed on the floor in front of the rider to help them improve their position as they pedal

The observant among you may have realised I haven’t once mentioned my training up to this point. No, I wasn’t banking on aerodynamics alone slashing my times, but it was going to have to do a lot of heavy lifting. During the summer I was some way off my fitness from last year. With half of March and April wiped out by illness, sporadic riding rather than structured training the rest of the time, and a week at the Tour de France, meant I was not hitting the numbers I hit in 2021. Not consistently anyway.

Several TT’s that were in my diary were cancelled, and before long I was worrying about having a set of rides to meaningfully compare to last year. Something that is difficult at the best of times.

At my club’s interclub TT against our rival club on the Bletchingley course in Surrey I posted a 27:57 minute ride, six seconds slower than last year. But that’s not the whole story. My average power had been 16 watts lower than last year, but I put 1.03 minutes into a rider who beat me by 14 seconds in 2021 and went seven seconds faster than another rider who I had fully expected to beat me. Were they off form? Was it a slower night? I’d put out less power, gone only a handful of seconds slower and beaten two riders who usually beat me. It was a good result, even if it didn’t particularly feel like one.

On the even shorter Newdigate course, I posted an 18.44 minute ride early in the season on the Venge, then two months later, on the Shiv, I lowered that to a 17.40, sadly with no power numbers to compare. A faster night? Probably. But the rider who beat me in May only improved by 24 seconds when I’d improved by 1.03min. The rider in third had gone faster by just two seconds.

The improvements were there despite my inability to hold the position honed in the windtunnel. But nothing was going to give conclusive proof.

The final test

As the summer evening TT season petered out in late August I felt like there had been no end point or conclusive set of results with which to neatly summarise my little aero project so a quick reassessment had to be made. I decided to ride a 25, a distance I hadn’t ridden since the late 90s when I first started racing. The aim would be to break the hour.

With an open TT cancelled midway through (see note at end of feature) the final test would be on the E33/25 course. A triangular circuit completed twice on single carriageway A roads in Cambridgeshire with a total elevation of 190m. Originally proposed as a SPOCO course it wasn’t a given that I could break the hour, especially as I was riding it alone, on a random Thursday afternoon at the end of September.

The pressure was on. Thousands of pounds worth of kit (a HED rear disc and front wheel had since arrived for testing) and input: I had to do it. Setting off on a rolling section of road I tried my best to hold back on the inclines, trying to keep it under 350 watts at all times and simultaneously staying as aerodynamic as possible. Basically, head tucked in and shoulders shrugged.

I had reduced the display on my computer to show just speed, watts and elapsed time, so I had little to distract me while giving me the info I needed to ensure I was pacing myself and staying on target. I held an average weighted power of 222 watts (3.55 w/kg), fading ever so slightly at the end and eventually stopped the clock at 59.00, just after passing the finish line signalled by Dr Hutch, so adjusted my time down by one second for extra kudos.

I’d done it. I’d broken the hour, and what's more done it on 48 hours notice, without any recent focused or consistent training, no structured warm up and without the extra impetus of being part of an event.

Hutch made an educated guess that on a fast course, that time would drop further still, perhaps even as low as 55 minutes, and that was enough for me. The aero tech and work on my position had allowed me, a very average time trailer, without huge watts to spare, to post a good time, when in a state of fitness that really wasn’t conducive to it.

Would I have been happy had I spent thousands of pounds of my own money (rather than borrow test kit) and not get that conclusive answer or result I was hoping for? I probably would. The results were good, if not spectacular, the Shiv is a superb bike to ride at speed and as a learning experience it was fascinating.

I’d learnt that the aero quest is an ongoing project, with an indefinite number of tweaks to be made. But more so, as I compared my times with those from last year I was reminded that while money can buy you speed, time is a more valuable commodity. Time spent training, and ideally in the TT position.

I can turn up to a local TT on thousands of pounds worth of kit, get some admiring comments and post a good time, but I imagine I’ll never be fully satisfied. Always thinking, “if I’d done a few more miles, raised my hands, got my head down lower…….. I could go even faster.” But I guess that’s what keeps us coming back.

Editor of Cycling Weekly magazine, Simon has been working at the title since 2001. He first fell in love with cycling in 1989 when watching the Tour de France on Channel 4, started racing in 1995 and in 2000 he spent one season racing in Belgium. During his time at CW (and Cycle Sport magazine) he has written product reviews, fitness features, pro interviews, race coverage and news. He has covered the Tour de France more times than he can remember along with the 2008 and 2012 Olympic Games and many other international and UK domestic races. He became the 134-year-old magazine's 13th editor in 2015 and can still be seen riding bikes around the lanes of Surrey, Sussex and Kent. Albeit a bit slower than before.