'Our cars were set on fire by Basque separatists': The inside story of ITV's Tour de France coverage

As another Tour comes to a close, we spent the day hearing three decades worth of stories from the team behind ITV's coverage of the biggest race in cycling

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This story was published in 2019.

"I got a call at 6.30 one morning when all of our cars had been set alight in San Sebastian by Basque separatists on the eve of the prologue the 1992 Tour," says managing director Carolyn Viccari, "that was a pretty stressful moment that sticks out."

"It happened in the middle of the night for the crew out in France, suddenly the guys could hear alarms and fire engines and were thinking what on Earth had happened.

"The race had just gone into San Sebastian and we’d parked up in a town square and any car with a French number plate had been torched."

Pyromania aside, the stresses endured over three consecutive weeks of work by the team behind London on ITV's Tour coverage have lessened over the years, the result of the expertise gained due to a number of them counting more than 20 Tours on their broadcasting palmàres.

Gone are the days when satellites were temperamental and sometimes wouldn't provide enough race footage for the highlights show, as well as the fax machine that was used as the quickest way to get the results of the stage over from France, once the most vital piece of equipment they owned.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Carolyn Viccari started working on the show in 1986 as a production assistant. Three decades later she's managing director of Vsquared TV, the production company ITV entrust with producing their Tour coverage, and oversees the operation in both London and France.

Her office is the first door on the left as you enter the second floor of the building they take over for July in Ealing Studios, West London. This means she'll hear around 25 "good mornings" as the team arrive between 9-10am before bunkering down in edit suites, ordering their toast and one of many cups of tea from a runner, settling in for yet another day's racing.

"The pressure is now on making a really good programme," Viccari says. With footage of the actual race previously at a premium, the tables have turned and every single minor incident is spotted and dissected on Twitter, meaning not only can you not miss anything but that the programme needs to bring more than just the day's action.

This task is made easier by most of the team being followers of the sport, and if you weren't a fan heading in to work on days filled with undulating French countryside and doomed breakaways from nondescript Frenchman, it wasn't long before Tour fever got you.

"We are fans, I don’t think you can cover the sport for this long and not be," says director James Venner, the 'V' in his surname being given to Vsquared. His father Brian is now chairman of the company, having worked many Tours back in the day, and before that being in charge of the BBC satellite link to Apollo 11 fifty years ago.

Having television galleries and production offices filled with fans of the sport they're being paid to cover isn't uncommon, but in cycling, with the heightened sensitivity concerning it's relationship with doping, it throws up the conflict between being a broadcast professional needing to make a show and being a fan somewhat plugged in to whispers and rumours of what may or may not be bubbling along under the surface.

"When you interview someone these days you don’t know if tomorrow they’ll be found out to be doping," Venner says. "You kind of have to suspend your disbelief when you’re covering it.

"I remember with the Armstrong stuff people criticising Sherwen and Liggett, saying they were complicit, but it’s much more difficult, all you can do is call the race and cover it live as if what you’re watching is real. You can obviously have a bit more room for discussion in the highlights.

The conversation with a number of people, like any about cycling, naturally and eventually leads to Armstrong. "In 1999 we were like this is a bit odd and gradually throughout the seven years your belief got less and less but it’s very difficult without hard proof to go on air and accuse someone of something. But hopefully you build in a bit of scepticism into what you do," Venner says.

Chris Littleford lives out in Spain, but returns to London as one of the producers for the Tour every year. "We’d all heard the stories [about Lance] and we knew people working directly out on the Tour. Everyone was talking about the possibility that this guy wasn’t clean," he said.

"The whole drugs thing is quite a difficult one," he continues, "especially as a fan as well, because you want to believe it’s clean but when you work on it you know a lot more about the sort of stuff that goes on behind the scenes, you know that it’s not necessarily true and that can dampen your enthusiasm."

These are conversations usually left for after the closing montage of the highlights show has rolled out at 8pm and the production team cross the road to Crispin's Wine Bar, the sort of life-affirming establishment that makes spending the entirety of July sat in the dark inside a TV gallery seem preferable to the reality of the outside world.

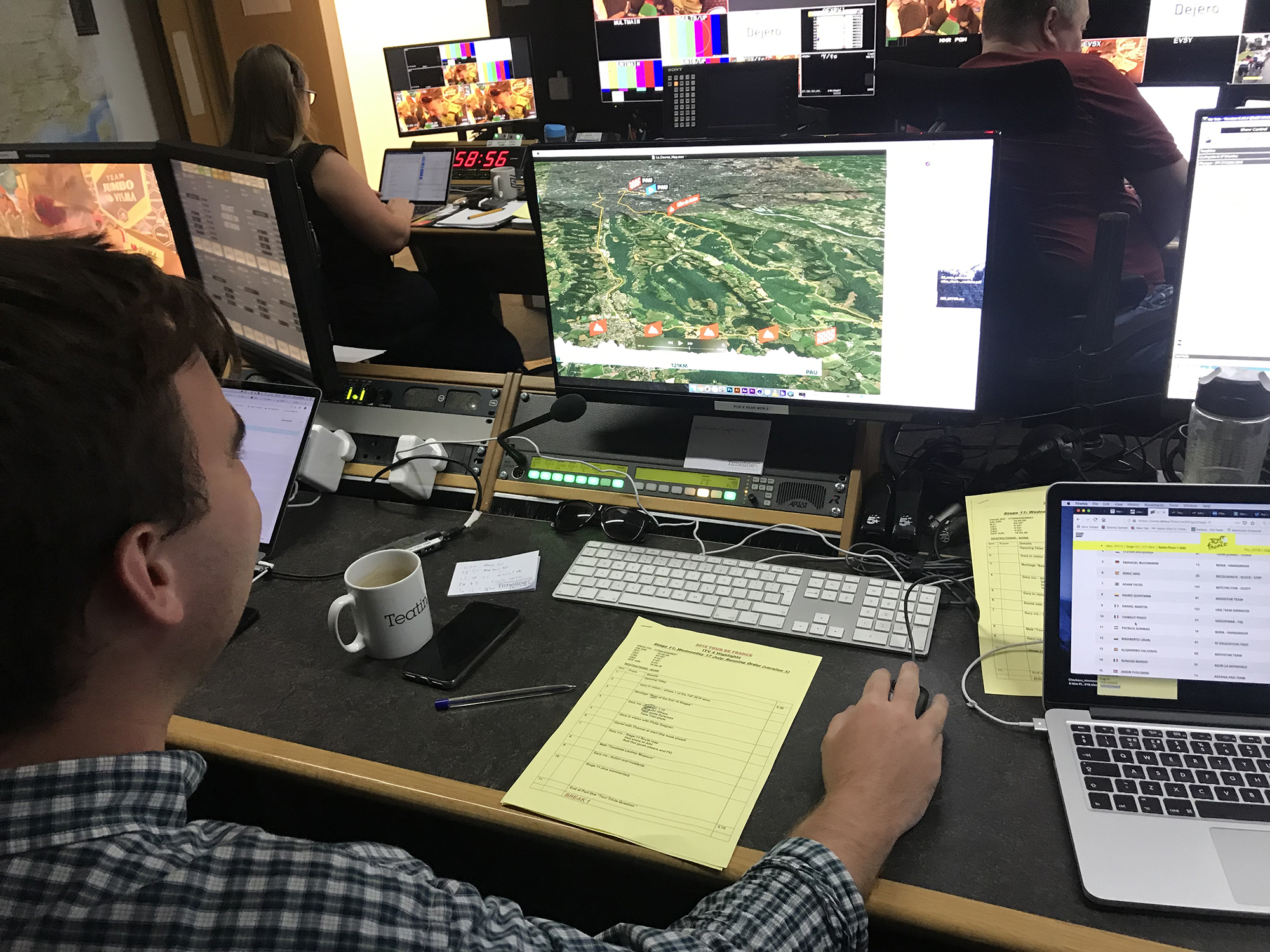

Every morning around 11am there's a production meeting where the various parts of the show are handed out to different teams of editors and producers. The gap between the morning meeting and the live show going to air as racing beings contains two of the most important decisions made each day, unbeknownst to the viewers at home.

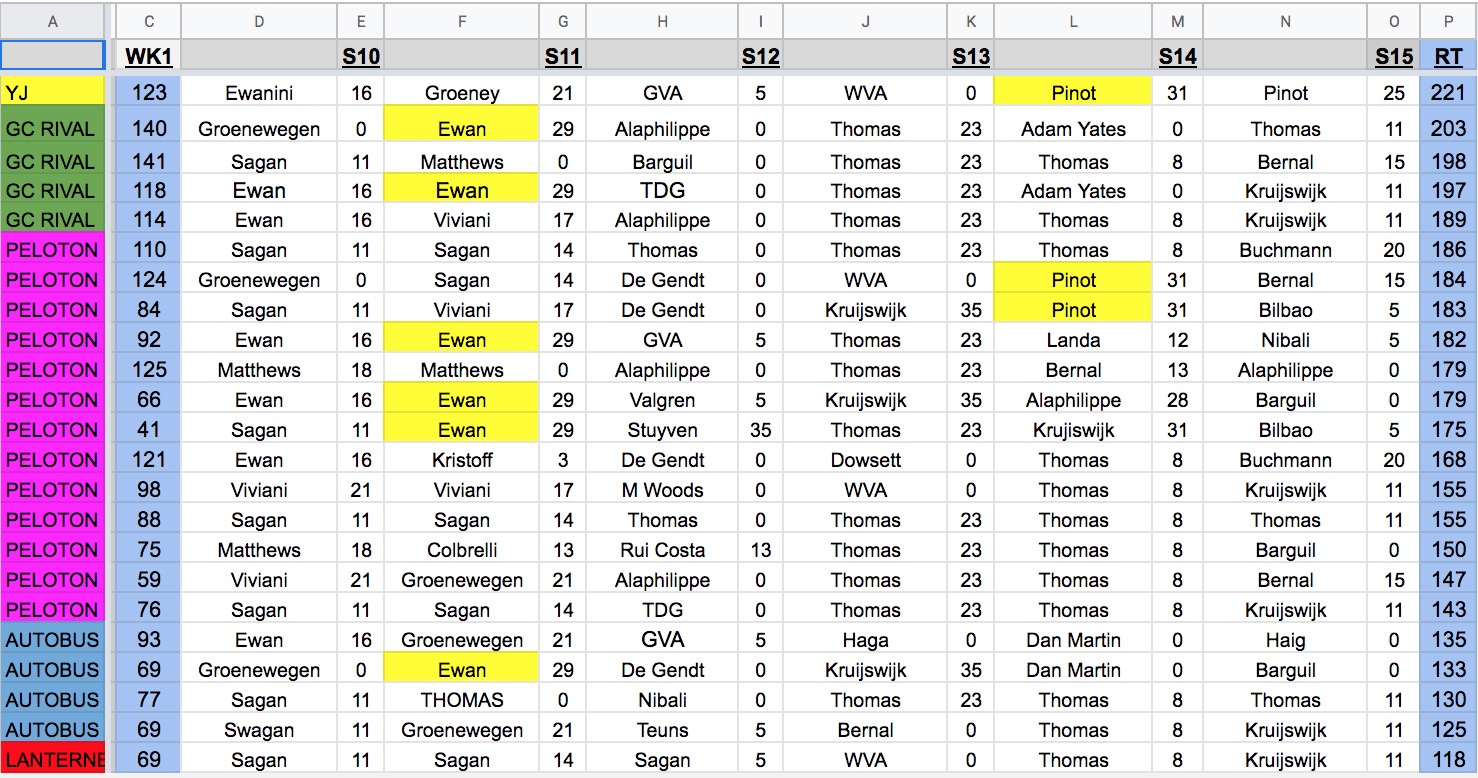

The first is your pick for the prognostic game, where you add a new name of who you think will win the day's stage to an expansive excel spreadsheet filled with caveats and mathematical additions years in the making.

Points are given if your pick is placed in the top 10, with the the bookies odds divided by their placing and added to the score to encourage competitors to pick an outsider. The £200 grand prize or doughnut run for the lanterne rouge each rest day ensures both ends of the standings remain interested right up until the Champs-Élysées.

"The prognostics is great as it gives everyone a reason to be interested every day," says Phil Long, who does the graphics and has been accused in the past of prognostical-doping after discovering that picking Peter Sagan for every sprint and Chris Froome for every other day delivered him the maillot jaune. This caused a reaction from the master of ceremonies Chris Littleford: "As Prudhomme changes the rules of the Tour every year we have to change the rules for the prognostics."

The game is more than a way to keep everyone interested on the dreary sprint days where not much happens, it is credited with turning those on the team who are their just for a job into cycling fans, and soon find themselves willing Yoann Offredo on to make the breakaway stick.

The second important decision is lunch, menus from various eateries are meticulously poured over despite them rarely changing and being outdated with the wrong prices, which makes the challenge of staying within the allotted £7.50 budget a task to approach with trepidation.

There are two runners per day who go round patiently waiting for everyone to eventually make the same choice as they did yesterday. Today it's Miriam, who is on her maiden Tour de France to earn some money before she returns to Norway for acting school in the autumn. She tells me she couldn't care less about the racing but stares blankly into the distance when I ask how many cups of tea she reckons she's made this Tour.

"100 cups a day maybe, at least actually. Some people drink five to ten a day, and some people have three sugars, it’s insane, especially as I come from a non-tea drinking country," she says.

Jonny, on the other hand, is 22 and has just graduated from the University of Leeds. He's worked the Tour in the summers throughout his degree and has now caught the cycling bug. He started going on rides in the Dales when he got back to uni one autumn and then started bike-packing regularly, such was the inspiration in between making cafetières.

Lunch usually arrives just as Dan Deakins needs his hands to start typing, not stopping until the live feed from France returns to the comforting glow of the multi-coloured bars to signal another stage is done.

Dan has one of the more enviable jobs for fans of the sport, involving watching every single second of the race, uninterrupted by adverts.

As the logger, it's his job to create a record each day of everything that happens during the stage. Every camera shot, every chateau, every Mavic moto holding up the time gap for the breakaway.

Dan's a cycling fan who managed to get the job by circumstance. After messing up his A-levels he had to find any uni that would take him so he could get a degree. Picking out the easiest one from the list, he plumped for sports journalism.

Just by coincidence, Ned Boulting, who commentates out in France for ITV, came in to give his class a talk one day about Lance Armstrong, the year after he'd confessed to doping.

"I was the only one who a) knew who Ned was and b) knew about cycling, so me and Ned sat about chatting for two hours after the lecture and then I took my chance and asked if he had any contacts to get me in."

When he's not logging the umpteenth piece of underwhelming field art at the side of the road on a flat stage, Dan works as a private hire chauffeur for pharmaceutical companies. He says it's all bit high-brow "and you've got to be nice and polite to everyone all the time," a bit of a departure from when I can later hear him in the next room cheering Caleb Ewan (Lotto-Soudal) on to his maiden Tour victory.

However, his regular day job isn't totally removed from the world of cycling, saying he once picked up people who were working on the Chris Froome salbutamol case, admitting the drive wasn't long enough for him to ask as many questions as he'd have liked.

After Ewan wins and the appropriate points are added to the correct column on the prognostics sheet, those in the gallery come off air and the edit suites spur into action to get the highlights show ready for a few hours time.

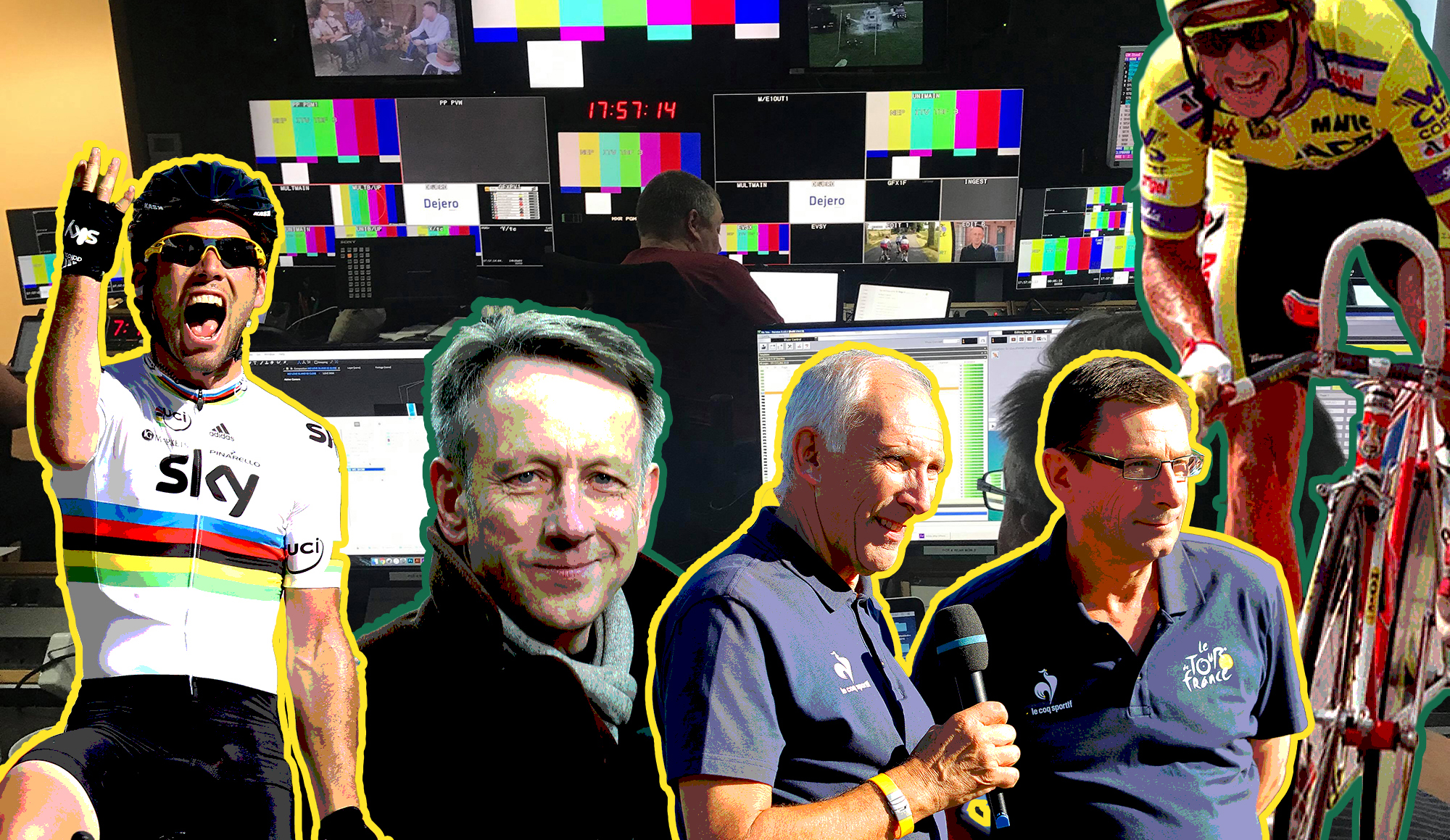

Peter Kennaugh is the newest face to stand alongside Gary Imlach and his Saharan sense of humour, after Chris Boardman finally reclaimed his July after years of first racing and then broadcasting, apparently spending his first day of Tour freedom in his garden enjoying a beer.

"I’d like to think the team is almost a family," says Viccari, "we don’t lose too many people along the way."

"Obviously Chris Boardman leaving at the end of last year was a blow, but it was understandable, he’s done it for a long time. But instead of being like 'oh my god what are we going to do' it’s a chance to try out new people."

These days they can't move for British cycling stars to hit up for a bit of camera time and post-race analysis, which hasn't always been the case.

"When we were looking for pundits in the 90s there was nobody really and Chris was a shining light when he started winning yellow jerseys. But now there’s a whole generation of riders who have ridden the Tour and have the palmàres to talk sensibly and intelligently about it," says Viccari.

The British dominance of the past few years was initially treated with some scepticism, not believing the bluster from Team Sky saying they'd have a British winner within five years, "although we always hoped they would" Viccari adds. The rise of British cycling has undoubtedly been good for business.

"Although, we’ve had to focus on the Brits for the past five years because they’ve been winning every year, but we try to be balanced and not be too home nations about it."

Past and present larger-than-life characters have always still received their appropriate air time. With Peter Sagan taking over from Thomas Voeckler and Jens Voigt as the favourite for a soundbite, usually invoking an eruption of laughter from across the floor when the Slovak gives a one-word answer to an earnest question from Matt Rendell.

Among the ups of the jokes and enjoyment of working on the Tour are the inevitable downs. Equidistant between this year's Tour and the 2018 edition, Paul Sherwen died suddenly of a heart attack at his home in Uganda.

Phil and Paul were the voices of cycling for a generation of fans and long time commentators for the British production. The team were in touch with Phil before and throughout this year's race, as he embarked on his first Tour without his long-time co-commentator, which he was doing with understandable trepidation.

"It’s quite odd the level of sentiment that comes from a group of people who only ever spend time with each other for a month of the year at a time," says Viccari, "but I guess, in another way, I've also known Paul since 1986".

As the Tour ends, the biggest race on the cycling calendar is completed. But for the ITV team it will only be a few weeks respite until the next challenge, La Vuelta a España.

Jonny was Cycling Weekly's Weekend Editor until 2022.

I like writing offbeat features and eating too much bread when working out on the road at bike races.

Before joining Cycling Weekly I worked at The Tab and I've also written for Vice, Time Out, and worked freelance for The Telegraph (I know, but I needed the money at the time so let me live).

I also worked for ITV Cycling between 2011-2018 on their Tour de France and Vuelta a España coverage. Sometimes I'd be helping the producers make the programme and other times I'd be getting the lunches. Just in case you were wondering - Phil Liggett and Paul Sherwen had the same ham sandwich every day, it was great.