'You've heard of junk miles? Well I've invented junk intensity' – Dr Hutch on why you should ditch training and just go for a ride

Half-arsed training isn't even fooling Dr Hutch himself

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

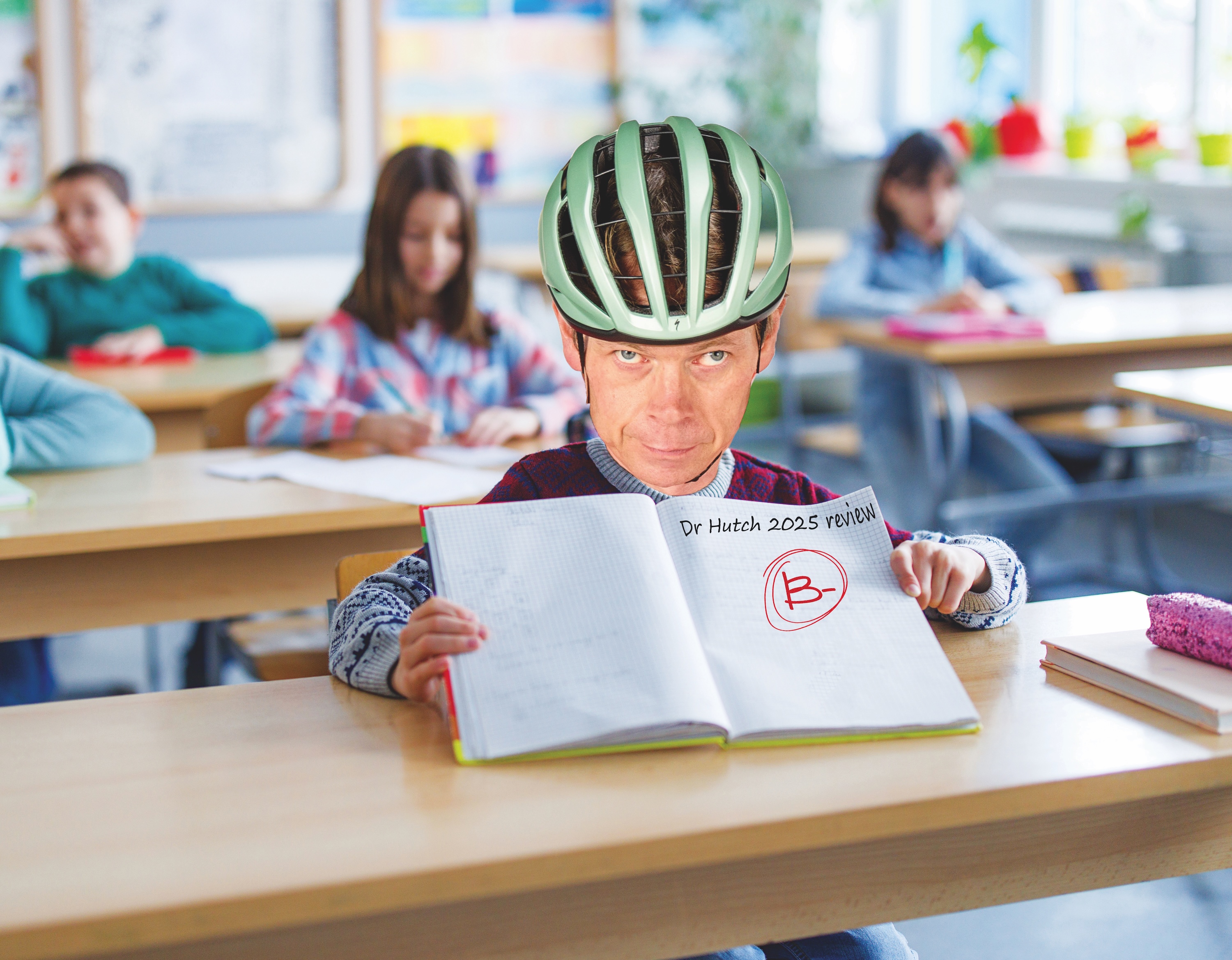

I’ve decided to review my own 2025 season earlier than usual this year, mainly to put it out of its misery. It’s a B minus at best. A “Needs work”, or a “Michael is easily distracted and this year completely failed to make the most of his admittedly limited abilities.”

My target-setting was non-existent. The last few years have seen the careful selection of things like championship races which I obviously wasn’t going to win, but which at least provided a bit of structure for the mediocrity and, when the day arrived, a reminder not to be too ambitious. This year I set out to “enjoy a few local races”, and that’s not a target, it’s just an excuse for a few beers afterwards.

Multiple national road champion on the bike and award-winning author Michael Hutchinson writes for Cycling Weekly every week.

As if to prove the importance of target setting to a successful season, my training matched the targeting perfectly. Other than one or two social rides, I didn't ride for longer than 90 minutes between December and July. I managed better than that the year I broke my hip, and indeed better than that while I still had a broken hip and lived in fear of getting a puncture because while I could ride a bike I couldn’t stand up unsupported.

I keep setting out on what were intended to be two-hour rides, planned as a stepping stone to some three-hour rides, and coming home after an hour and a bit. I’m in a destructive cycle where I don’t feel like I’m doing enough riding, so to make up for it I ride harder. That means there’s less of a straightforward out-in-the-countryside pleasure in it, so I do less again.

I don’t do it hard enough to compensate, by the way, just hard enough to put myself off the whole idea and keep the rides short. You’ve heard of “junk miles?” as a description of distance covered to no great training purpose? Well, I’ve invented “junk intensity”.

I was actually at my fittest at the end of February, because I spent most of the winter just riding e-races against random fields of strangers from all over the world. The races were short, and, more often than not, very hard indeed. Then, when spring arrived, I started proper training, which ended up being half-hearted rides focussed mainly on swerving round potholes.

I’m still not nearly as bad as I deserve to be. This has been the story of my cycling life – I’ve complained for years that I never get as much benefit from training as I feel I should – long months of carefully structured work produce gains much smaller than I’ve seen in others, even others that I’ve coached.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But I’ve always been less grateful for the opposite effect, which is that when I don’t bother training I never fall as far as I should. Last year I did some real training, and I could manage a very credible 405 watts for twenty minutes. This year I’ve trained like a moron and I can still do 395.

You might feel like this is living the dream – and to some extent it is. But it’s one of the reasons it’s so hard to motivate myself. I don’t get much from training that I don’t already have. I imagine being incredibly rich has a similar effect on your work ethic, but I also reckon being a billionaire would have compensations that comfortably eclipse being able to beat a Belgian called something like ZZZTopMerckx to the top of an imaginary mountain on Zwift.

In a way the answer is obvious – give up on training and just go for a ride. In many ways that’s the purpose of my earlier than usual season review. It’s a respectable way to bin the whole thing and just have fun.

Of course, that is probably the moment that I’ll suddenly be inspired to do some long rides and finally get some form together. ZZZTopMerckx, you’ve been warned. I’m coming for you.

Great inventions of cycling: sweat

Sweat is a liquid emitted from pores on the skin of humans (and a few other animals) in response to a number of stimuli, including high temperatures, physical exertion and fear. All of these are highly relevant to the sort of sportsperson who enjoys riding in the summer, riding hard in the summer, and just occasionally gets things horribly wrong. (Who among us has not squirted sweat from every pore instantaneously on realising they’ve committed themselves to a 30 kph corner at 50 kph?)

Humans developed the ability to sweat around 2 million years ago, around the same point we lost our fur. It provided a valuable means of thermoregulation in hot African environments.

In general, the fitter you are, the more you can sweat, and the more dilute your sweat will be. A top sweater can lose up to four litres of sweat an hour. This doesn’t sound all that much, but when dripped onto the floor of a warm public gym, is sufficient to get you banned for life.

Sweating works simply by allowing evaporation off the skin, which cools the blood vessels which funnel cooler blood back into the core of the body. The average human has two-to-four million sweat glands. I often suspect that cyclists have many, many more.

Michael Hutchinson is a writer, journalist and former professional cyclist. As a rider he won multiple national titles in both Britain and Ireland and competed at the World Championships and the Commonwealth Games. He was a three-time Brompton folding-bike World Champion, and once hit 73 mph riding down a hill in Wales. His Dr Hutch columns appears in every issue of Cycling Weekly magazine

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.