Ed Clancy's retirement signals end of an era for British team pursuiting

Seven world and three Olympic titles make Clancy the most decorated team pursuiter in history

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Great Britain won their first team pursuit world title in Los Angeles back in 2005, a young rider who’d ridden the qualifying round but not the final, was taken on to the podium by his more experienced team-mates to claim his medal and world champion's jersey.

Sixteen years, seven world titles and three Olympic golds later and that not-so-young rider bowed out of the sport in Tokyo. In an emotional track centre interview with Eurosport, Ed Clancy, now 36, told his old team-mate Bradley Wiggins; “I’ve pushed this body as far as it will go, mate.”

An operation on his back in 2015 got Clancy through to the Rio Games where he won his third gold, but he’s been managing the injury ever since. It flared up in the qualifying in Tokyo and he had to pull out of the round one races where Denmark knocked out Great Britain - literally and figuratively - and into the 7-8 final. It’s the first time GB haven’t medalled in the men’s Olympic team pursuit since Atlanta 1996.

Back in 2005, when the GB team began their period of consistent success and Olympic domination over the men’s team pursuit competition, one of the GB coaches told me that Ed Clancy in the ‘rider one’ position was probably the best team pursuiter in the world.

His skill was the ability to get the team off to a fast start in the opening one-and-a-half laps and then still be pulling turns in the final kilometre. Clancy’s physiology was that of a sprint endurance athlete, someone who could ride a one-minute kilo from a standing start - as he would in a brief sojourn training and racing as a sprinter post-London 2012 - but also last a full four kilometres.

It was this ability to soak up that opening effort that does so much damage to the muscles, recover while riding in the chain at 60kph plus, and pull turns in the final half of the race without slowing the team down that singled Clancy out as something of a team pursuiting phenomenon.

Ed Clancy and Ben Swift training in Majorca ahead of the London 2012 Olympic Games

Early years

Clancy is a product of British Cycling’s then named Olympic Academy. One of the first intakes in the under-23 program set up and run by Rod Ellingworth back in 2004. Clancy spent his formative years living and training with riders including Geraint Thomas and Mark Cavendish.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

He was a formidable lead out man for Cavendish when outside of their track program they raced for German amateur team Sparkasse in 2005 - 2006. Some of the wins that Cavendish racked up in this period were what caught the eye of Heiko Salzwedel and Cavendish, Thomas and Clancy were all for a short time mooted to join T-Mobile. In the end only Cavendish would.

But, despite his performances as an amateur Clancy's talents weren't suited to the European road scene and instead he spent his career racing on the domestic scene, in the main with John Herety's Rapha backed teams where he was given complete freedom to mix his road and track programs.

Clancy's sprint endurance abilities meant he was perfectly suited to the UK's criterium scene which complimented his track training. While Thomas remained an integral part of Britain's team pursuit quartet right through until London while racing with Barloworld and then Team Sky, Clancy proved that a European race program wasn't necessary to support team pursuiting.

Ed Clancy riding for JLT Condor in the Tour Series

Team pursuit progression

He was in fact the first of a new breed of pursuit rider whose physiology has seen the event go faster and faster. What once made Clancy unique is now de riguour as the speeds and gearing used means the 4,000m pursuit is a series of sprint efforts for the riders involved.

While there is talent coming through behind Clancy - Ethan Hayter and Ethan Vernon are 22 and 20 respectively - losing such a talismanic figure is going to be tough on the team, especially as it coincides with a period of development never before seen in the discipline.

The event is well used to seeing world records tumble at Olympic Games, it’s happened on each occasion since Athens 2004 as teams plan their four-year cycle around the two days of racing, and save their full aerodynamic package for the competition.

In 2008 GB, led by Ed Clancy (then 23 years old), rode to gold in a world record time of 3:53.314 minutes, three whole seconds quicker than the world record they had set at the World Championships in Manchester earlier that year.

It was another four years before Great Britain, still led by Ed Clancy, would break it again at the World Championships in Melbourne. At the London Games a few months later the time would eventually come down to 3:51.659. An improvement of just under two seconds in the four-year cycle.

Four years later and the British team did it again in Rio, but this time the team, still led by Clancy, were able to shave just one-and-a-half seconds off the world record. Australia had won every world title in the intervening years between London and Rio, but the British squad pulled it together in time for the Games, winning gold with a 3:50.265

Between the 2008 World Championships and 2016 Rio Games the world record was broken seven times by a British team who lowered it by 6.345 seconds over the eight years. (More world record times were set in that period, but times that are immediately broken in a subsequent heat aren’t always noted.)

Ed Clancy led each of those teams as rider one, the most important and challenging position in the four-rider line up. The six other riders with him throughout those years were Wiggins, Geraint Thomas, Paul Manning, Pete Kennaugh, Steven Burke, and Owain Doull.

After the world record was chipped away at in those periods it’s now been blown out of the water with aerodynamic development, bigger and bigger gears, and race strategies designed to suit the strengths of the riders in a team.

In the three years and four months since April 2018 when Australia became the first team to break the three-minute and 50 second barrier at the Commonwealth Games, the record has tumbled to an almost unimaginable 3:42.032, the time set by Italy as they won the gold medal.

Britain’s time in qualifying, a national record of 3:47.507 - a three-second improvement from Rio was, quite incredibly, way off the pace. They improved to 3:45.636 in their final ride in Tokyo to claim seventh place in the competition.

In the list of all-time fastest rides that puts them in eighth place. That ever-evolving list, once full of times set by GB and Australia at the most recent Games, now includes times from five nations. Britain's world record in Rio now isn't even in the top 40.

This rapid improvement has seen Great Britain a little left behind in the discipline after a record-breaking run of three consecutive wins in the event. While British Cycling won’t be hitting the panic button (performance director Stephen Park tells us in this week’s magazine - on sale Aug 5 - that the federations diversification in to BMX and mountain biking where they have already won five medals is in part down to the sheer amount of time and money required to continue to focus on the track events), they have lots of work still to do as they build towards Paris 2024.

One problem for British Cycling is that they made many of their gains years ago. Beijing 2008 was where their Secret Squirrel program, famously led by Chris Boardman, made huge aerodynamic gains. He spent hundreds of hours in the wind tunnel coming up with a skinsuit that was rumoured to have saved them several seconds in the team pursuit. It was banned soon after.

Having used all the new kit they'd developed in dribs and drabs at minor events in order to test it and get it past the commissaires, they rolled it all out in Beijing and dominated across the track events. Not just winning, but in three events taking the silver medal as well.

Much of the kit was made bespoke. One Dutch paper at the time quoted a dejected sounding Theo Bos saying they’d heard the British team had a new crank that was so strong you could hang a lift full of people from it. While this was clearly never tested, it demonstrates the psychological advantage the British team had at the time.

They made more gains in the build up to London, bringing in the use of different fabrics on different parts of a skinsuit tailored to an individual rider, with seams placed in just the right position to work as aerodynamic trips. The suits were made by Sally Cowan, a seamstress from Derbyshire who is credited with helping various sports from cycling to skeleton win over 100 Olympic medals in the last two decades.

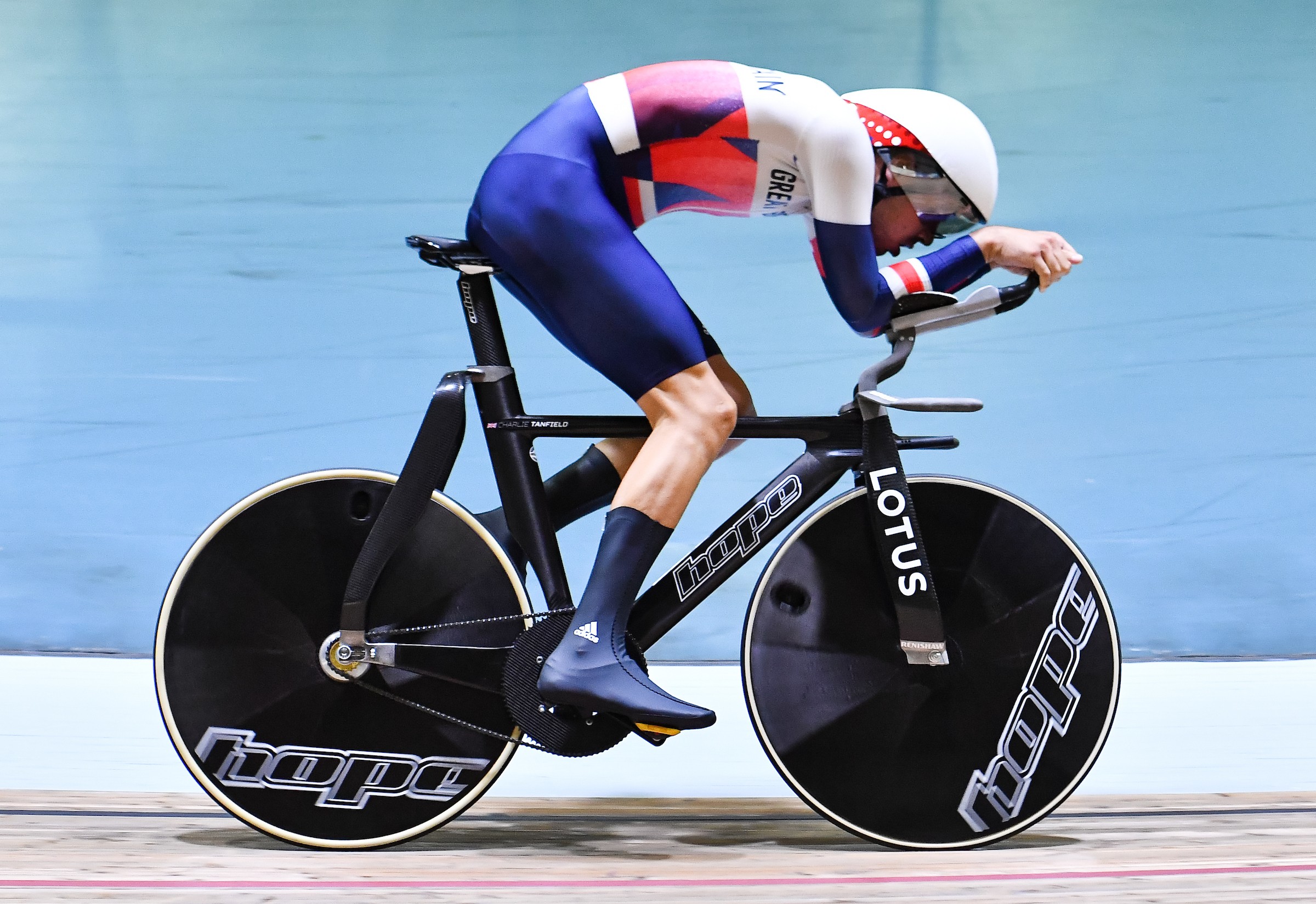

There were gains for Rio too, as former F1 aerodynamicist Tony Purnell came to work for the team, although it seemed they were becoming smaller and harder to find. The belief is the gains made in this latest cycle were smaller too. This despite the eye-catching Hope bike and the rumour that the British team have registered nearly 2,000 bits of equipment with the UCI prior to Tokyo.

But all the major track cycling nations now have very, very fast skinsuits. Even if a nation doesn’t make their own brands like Silverstone based Vorteq - used by the Russians - can make anyone a suit for a cool £5,000. Much of the aero kit and understanding in the pro scene has trickled down from the track programs.

Many nations have bespoke bikes and kit made for them too. These are then put nominally on sale to the public in order to navigate the UCI’s rules on kit being available to everyone. It’s not a tactic that always works, as Australia painfully found out in their TP qualifying round.

So any aero gains Great Britain have made are now largely cancelled out, or even bettered by their rivals. A world-class aerodynamic and kit development program are needed just to stay in the medal hunt. Not exactly what the UCI had in mind as they tightened up their tech regs over the decades.

What’s clear is that long gone are the days when any nation can dominate across the track disciplines; sprint, endurance, male and female. Male endurance events are no longer GB versus Australia just like sprint events don’t come down to GB versus France and Germany.

The Netherlands have perhaps the best sprint program in the world right now, the French and Germans remain strong, while the Danes have finally put their excellent talent development program (they have for years been producing incredible under-23 riders) to good use and combined it with the aerodynamic knowledge of Britain’s Dan Bigham to become the leading force in team pursuiting.

Italy are once again to the fore in the men’s, anchored by the mighty Filippo Ganna, Australia are still a force to be reckoned with on the men’s side while New Zealand are capable of getting in the mix too.

The same is true in the women’s events. The sprint events are wide open with Germany, China, and Russia all producing fast riders, and while Australia have slipped away on the endurance side and America have stagnated, Germany have burst through to become Olympic champions.

Losing their crown in the women’s team pursuit will also hurt in the British camp, but a silver medal and two new national records along the way will soften the blow and give encouragement for Paris.

A silver in the men’s team sprint on day two of the track racing means GB has won two silvers in four events so far. Add those to three golds, a silver and a bronze from BMX and mountain biking and Britain are currently top of the cycling medal table with seven medals, and the Netherlands just behind. No other nation has won more than one gold medal.

So while Britain’s position at the top of team pursuiting has slipped off over the horizon, there is still everything to play for in a new era for the sport, and British Cycling.

Team pursuit progression in Olympic cycles

2004 Athens - 3:56.610

3.296 seconds improvement

2008 Beijing - 3:53.314

1.655 second improvement

2012 London - 3:51.659

1.394 seconds improvement

2016 Rio - 3:50.265

8.233 seconds improvement

2021 Tokyo - 3:42.032

Editor of Cycling Weekly magazine, Simon has been working at the title since 2001. He first fell in love with cycling in 1989 when watching the Tour de France on Channel 4, started racing in 1995 and in 2000 he spent one season racing in Belgium. During his time at CW (and Cycle Sport magazine) he has written product reviews, fitness features, pro interviews, race coverage and news. He has covered the Tour de France more times than he can remember along with the 2008 and 2012 Olympic Games and many other international and UK domestic races. He became the 134-year-old magazine's 13th editor in 2015 and can still be seen riding bikes around the lanes of Surrey, Sussex and Kent. Albeit a bit slower than before.