Iconic Places: The Forest of Arenberg

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The stretch of cobbles through the Arenberg Forest, in Sunday’s Paris-Roubaix, is the most decisive and spectacular of the day. Cycle Sport’s Iconic Places series covered it in April 2009.

Words by Chris Sidwells

“The forest is Paris-Roubaix. It’s unique, only in this race do you have to ride through Arenberg, no other.” Franco Ballerini, Paris-Roubaix winner 1998.

What other sport could revere a one and half mile stretch of pit road, running dead straight through a threadbare forest of birch trees that look like they never see enough sunshine? Bring anyone here who hasn’t let cycling under their skin and they just won’t get it. The mountains have majesty, whether there is a bike in sight or not, this place is a grimy left over of a dead industry. It looks like Hell, but therein lies its appeal.

This stretch of cobblestones is the most famous part of the Hell of the North, the passage through Hades that forms the evil heart of Paris-Roubaix, the race they call the Queen of Classics. This is the Forest of Arenberg.

If a road can be an anachronism, that is what Arenberg is. It embodies the times past spirit of Paris-Roubaix, but the Tranchée d‘Arenberg (it’s sometimes called the Trouee d’Arenberg as well) has only been part of the race since 1968.

When it started, Paris-Roubaix didn’t need to find a place like this. If you drew a straight line from Paris to the industrial north in 1896 all you would find was cobbled roads.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The first Paris-Roubaix started on Sunday April 19, 1896. It was the idea of two manufacturers, Theodore Vienne and Maurice Perez, from the bustling town of Roubaix. The previous year they had built and opened the Roubaix Velodrome and wanted to publicise it with a race from the capital.

In those days the Nord department was the hub of French heavy industry. Today the countryside is dotted with preserved pit heads and slag heaps, but at the turn of the century hundreds of mines clawed coal from the ground, steel mills and other factories belched smoke into the air and people lived like nowhere else in France. It was Hell, a living Hell.

Into battle

But the phrase Hell of the North wasn’t coined until 1919. As the riders battled through what had the previous year had been one of the battlefields of the First World War, journalists following the race were horrified by what they saw. The land was devastated. Not a single tree was left standing, and there wasn‘t a field or road that hadn‘t been bombed.

As time progressed the Nord was rebuilt. World War II slowed development for a while, but in time, many cobbled roads were replaced with smooth concrete as France strove to modernise. And each year Paris-Roubaix lost a bit of its character, not helped by a growing inferiority complex among the village mayors of the north.

“During the sixties the mayors wanted to modernise everything, so if the race was routed through their village they made an order to improve the roads, because they didn’t want to be seen by the rest of France as being backward,” local rider and 1962 world road race champion, the late Jean Stablinski told Cycle Sport a few years ago.

Stablinski lived in the department all his life. He was born just north of Arenberg and later lived in Valenciennes, just to the south. He knew the area as well as anyone, so the organisers turned to him when they saw the teeth being pulled from their race. “I knew where there were hundreds of terrible cobbled stretches deep in the countryside, including the Tranchée d’Arenberg, which were to the east of the original route,” he told us.

Stablinski had a special knowledge of Arenberg. Before he even turned professional he worked in the mine at the southern entrance to the Forest.

“Not many people know it but an underground roadway runs directly below the Tranchée. I am the only man to have walked under and raced over the cobbles of Arenberg,” Stablinski revealed.

The Tranchée d’Arenberg helped to save Paris-Roubaix. More country stretches of cobbles were sought, and the race evolved into what we see today. There are tougher stretches of cobbles in the race, especially since the regional council spent 250,000 euros in 2005 to repair the Tranchée when, due to a combination of mining subsidence and centuries of wear and tear, it was deemed to exceed the limits of safety. But Arenberg hasn’t lost one of its dangers, a danger that makes a selection even before the cobbles start.

Speed trap

“The riders are still quite fresh, and there is quite a big gap after the last set of cobbles before you hit Arenberg,” says Quick Step [now Leopard-Trek] rider Wouter Weylandt.

“Before Arenberg it is like a bunch sprint in a major Tour. The favourites are often together, still watching each other and still with their teams around them, but they are fighting for their place, even using a lead out train to get onto the cobbles first. It’s 70 kilometres per hour, then you hit the cobbles. That is the difficulty and danger of Arenberg today.”

The road before Arenberg is slightly downhill, which helps build speed and was held to be one of the reasons why Johan Museeuw crashed in 1998, shattering his knee - an injury that led to other quite serious complications. The direction was reversed for one year, but it didn’t look right and had little effect on the speed.

Today the entrance to Arenberg is as it has always been, from the south, despite a terrible crash in 2001 when the leading rider, Philippe Gaumont crashed on the cobbles and snapped his femur. The riders turn right off the D13 road into the village of Bellaing and fly down the Rue Michel Rondel, out of the other side and past a row of neat former pit-owned houses on their right. Opposite these is the preserved Wallers-Arenberg mine, where Stablinski worked. Wallers and Arenberg are the villages on either side of the southern edge of the forest.

They bounce over a level crossing, then the riders are on the cobbles. The road through the forest is called the Drève des Boules d’Herin. The surface is a little more even since it was repaired, but the cobbles are still brutal. Add rain, an approach speed of 70 kilometres per hour, and you see that the Arenberg hasn’t lost its bite.

The dead straight route is lined by two cinder tracks. They are the way the locals go when they use this road. Separated from the cobbles by a strip of muddy grass on either side, they are a smooth respite that riders used to go for on race day. It was an amazing sight, the colourful group would spill onto the stones, filling their width, then fan out onto the smooth paths. As this appened, badly placed riders would try to overtake using the cobbled road. It was reckoned that a burst of 1,000 watts was required to gain a place on the cobbles at this stage.

Now the choice of path through the forest is largely restricted to the cobbles. The organisers place barriers at their edge and the riders have to go straight down the middle, but the power output required to do it is still prodigious.

Magnus Backstedt won Paris-Roubaix in 2004 and has studied this race for most of his career. If they gave out doctorates on Paris-Roubaix, Backstedt would have one.

“Every year I [went] to Arenberg to ride the stones before the race. I did some other stretches of cobbles, but always Arenberg. I’ve ridden it with SRM cranks and at full speed keeping with the leaders across Arenberg is like doing a 4,000-metre pursuit, the outputs are comparable. The problem is you have to do it again on the next stretch, and the next. Every time giving everything you’ve got. That’s why I love it,” he says.

Stab’s stone

The first part of the road is slightly downhill, then it drags slightly upwards, but not by much. A memorial stone to Stablinski, unveiled by Jean-Marie Leblanc in 2008, stands where the drag starts. The only way to ride is to push a big gear and let the bike find its way, trying to coax it along the smoothest line. It’s not easy alone, but surrounded by other riders, all fighting for position, only the best can cope.

“You have to be able to make decisions in a split second and get them right. Even though work has been done to make the route safer, weather conditions, crashes, even agricultural vehicles using the cobbles before the race affects their condition in a hundred ways and you must react correctly every time there is a change of surface,” says the 1990 Roubaix winner, Eddy Planckaert.

Some of the challenge of Arenberg was removed when the body count was getting out of order and it was re-surfaced, but Arenberg still retains its magic. It’s the place the fans most want to be on race day, the place where bike enthusiasts most want to ride if they visit northern France. On race day the crowd builds from early on. They line the strip of granite stones, their flags a colourful contrast to the spring green of the forest. They wait for the white-water rush of riders as they thunder onto the cobbles at the far end of the forest. Team helpers and supporters of individual riders crane their necks and look on in hope. Hope that their man won’t crash as the throbbing pack hurtles past.

They are gone in a flash, a few stragglers, a few more, some race vehicles, then nothing. There’s a pause, the fans process what they’ve just seen then they too drift away. As they do time seems to close behind them, Arenberg has played its part in Hell for another year and returns to living in its past.

Four men of Arenberg

Eddy Merckx

The early seventies saw nothing short of a war going on between Eddy Merckx and his rivals from the Flandria team. They were all Belgians, but Flandria were as Flemish as frites and mayonnaise and Flemish journalists accused Merckx of French-speaking affectations. In a country where the Flemish regarded their French-speaking compatriots as workshy freeloaders or snobs and the French speakers thought the Flemish were avaricious shysters or just plain common, this was more than sport, it was a battle of cultural identity and a class war rolled into one.

The first blow was struck when Merckx punctured just before Arenberg and Flandria’s Andre Dierickx, Eric Leman and the De Vlaeminck brothers, Erik and Roger, shot off the front. Merckx quickly re-joined Flandria’s chasers, then set off in pursuit on his own.

He ploughed through the gruesome conditions waiting in Arenberg, while everybody else slipped and slid in his wake, and by the end of the section he had caught his tormentors, who immediately desisted. Those who saw it reckon that nobody has ridden through the forest like Merckx did in 1971.

Later Merckx punctured again, and the same four Flandrias attacked, provoking another Merckx effort to bring them back. But when he did Roger De Vlaeminck punctured, so Merckx attacked, carrying on alone to win by five minutes 21 seconds, still the biggest postwar winning margin of Paris-Roubaix. It was the second of Merckx’s three Roubaix victories.

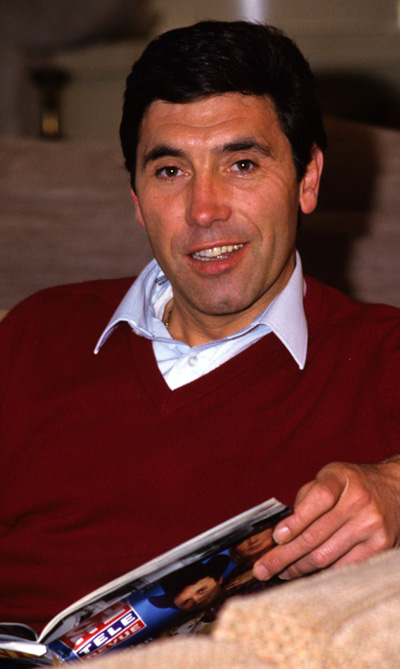

Franco Ballerini

The late Italian won Paris-Roubaix in 1995 and 1998, and he thought he had won in 1993 but lost by the narrowest of margins to Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle. He was built for racing on the flat over cobbles, his power output was prodigious and his 1998 victory was the purest demonstration of his ability, because he won by the biggest margin since Eddy Merckx in 1971.

Ballerini’s victory march began in the Forest of Arenberg, when he was one of 25 riders who survived at the front after a particularly bad passage. Ballerini remembers one thick knot of riders, who were stopped by crashes or punctures, and recognising one of his rivals. “I actually had to climb over Andre Tchmil,” he said.

Later Ballerini made his winning move on Mons-en-Pévèle, another five star section. Magnus Backstedt was directly behind him and Ballerini’s attack will be etched on his brain for ever. “He accelerated and got a gap, but I fought really hard to get across to him because Franco was so strong I was sure it was the winning move. He was a few bike lengths up the road, then he looked round, saw me and went again. I was flat out but he just accelerated away,” Backstedt says. Ballerini continued on his own, leading a Mapei one-two-three in Roubaix, the second time the team had done it.

Andrea Tafi

Tafi was second to Ballerini in 1998, and he was third in Mapei’s first podium filler in 1996, where their three riders entered the Velodrome together and the order they finished in was decided by Mapei’s owner, Signor Squinzi. Both placings disappointed Tafi beyond measure, but he made amends in 1999 by winning in the dream scenario of a lone victory while wearing the Italian national champion’s jersey.

Tafi wasn’t to be denied in 1999. He used the forest of Arenberg to make his first move of the day, dragging a group clear that again included two of his team-mates, Tom Steels and Wilfred Peeters. Tafi was owed by Mapei, so things looked good, but then the Italian punctured. Steels missed it, but Peeters nearly stopped in the road to wait for Tafi.

When they caught the leaders, Tafi just rode right by and continued on to take a sentimental victory in Roubaix. He was building a new house and wanted the cobblestone awarded to the winner each year to use as a keystone. When the organisers heard about it they gave Tafi another one to put on his sideboard.

Sean Kelly

Another two-times winner, Kelly also scored an outrageous double when he won Roubaix and Liège-Bastogne-Liège in 1984. It was also the year that Roubaix went back to Arenberg, after the forest’s owners had withdrawn it from the race in 1974.

The return saw chaos, all of the strong Renault-Elf team’s leaders crashed and none of their riders finished the race, prompting their manager, Cyrille Guimard to comment, “By the end of Arenberg half of my riders were flat on their backs, and the other half were flat on their faces.”

Sean Kelly was one of the few who stayed upright, although even he found it difficult. “I slipped this way and that and got forced off the road by other riders. I even ended up riding through the trees for a short while,” he remembers

Out the other end, Kelly waited until he had a group around him, then began to push. What happened next was the usual Roubaix attrition until there were 25 at the front chasing Alain Bondue, who had his team mate Gregor Braun with him.

Kelly identified Hennie Kuiper as the strongest man in his group, so with 47 kilometres to go, when Kuiper was at the back of the line on a stretch of cobbles, Kelly attacked. A talented young Belgian, Rudy Rogiers gave chase with Kelly. These two eventually caught Bondue. And that was the order at the finish; Kelly, Rogiers and Bondue.

Pro’s eye view

Belgian Paris-Roubaix winner Eric Vanderaerden tells us how to ride the cobbles of Arenberg

How important is the Forest of Arenberg in Paris-Roubaix?

Very important, but not important in that it finds the winner. Its importance is that if you make a mistake in the forest, it will have three times the consequences later on. Even a puncture sets you back more, because it’s so difficult to get service.

Did you have a tactic for the forest that you tried to use?

I would try to have a team-mate close by in case of trouble, then he could give me his wheel or bike. I tried to be near the front, but that was for safety and position. I wouldn’t push it there, it’s too early. Anyway, it’s hard enough just getting a good position and keeping it. That is enough to focus on.

Does the race slow down after Arenberg?

Not really. It’s a good tactic if you have team-mates with you to get them to ride hard on the smooth road just after Arenberg. That makes it harder to get back and if anyone has had trouble.

Did you have a line you would follow along the cobbles?

Generally the middle or the edge, but not all the way on either because there are holes and rougher bits that you must avoid. Also, the cobbles change in different weather. In the wet you must be much more aware and adaptable, and not fight your bike, just guide it.

Did you look at the forest before Paris-Roubaix?

Not always. Peter Post, my manager at Panasonic and my manger when I won, used to say that the cobbles at 50 kilometres per hour on race day are different to 30 kilometres per hour on a training ride, so riding them to practice doesn’t achieve much. We would get reports on their condition though. You know, whether they wet or dry, muddy or not.

Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/cyclesportmag

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.