Inside the mind of Dave Brailsford

Cycle Sport finds out what makes the Team Sky boss and possibly the hardest-working man in cycling tick.

Words by Lionel Birnie

This article first appeared in Cycle Sport May 2011

Step into Dave Brailsford’s office at Manchester velodrome hoping to garner some clues about his personality or management techniques and you’re likely to be disappointed. It’s minimalist to a degree that would make even a particularly fastidious interior designer from Sweden gasp in wonder. On his desk there is just a large, flat computer screen (Apple, of course), its keyboard and mouse. There are a couple of sofas flanking a small coffee table upon which a selection of cycling magazines has been fanned out. There’s no clutter. Only clean lines and neatness and very little in the way of personal effects. We could be in the office of a firm of management consultants. In a way, perhaps we are.

It is impossible not to allow your eyes to be drawn to the huge and imposing photograph that dominates the back wall of Brailsford’s office. The choice of picture perhaps gives more of a clue than its owner realises. It is a jaw-dropping image of the Great Britain team pursuit squad in precision formation at the Beijing Olympics. The gap between the rear wheel of one rider and the front wheel of the next is perfectly uniform, as if Brailsford has arranged them by hand. It is neat, ordered and symmetrical. And more than that, it captures and freezes for posterity a performance that comes as close to perfection as anything in the sport can. It was the day the British team set a new team pursuit world record on their way to Olympic gold.

This office is the closest Brailsford has to a base, although he spends nearly all his time on the road. We meet on the eve of the final World Cup track meeting of the season, as Brailsford is about to embark on the busiest period of a non-stop year, a time when his two jobs overlap the most. He runs through a dizzying schedule that takes him through to the Classics. The day after the World Cup he would head to London for the official handover of the Olympic velodrome, then on to Flanders for Het Nieuwsblad and Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne with Team Sky, then to Paris for meetings with his fellow team managers and the heads of ASO before following the first half of Paris-Nice and the second half of Tirreno-Adriatico in Italy. After that would come Milan-San Remo and a few meetings in Nice before flying to the Netherlands for the track World Championships. Then, on to the Classics.

Brailsford is British Cycling’s performance director as well as Sky’s team principal. The task he has set himself is daunting. It requires a workaholic’s constitution. Brailsford has to keep two very valuable plates spinning – British Cycling’s lottery-funded Olympic dream, and James Murdoch’s expensive new toy, Team Sky. Actually, it’s more like he’s trying to balance two extremely large bowls that have been filled to the brim. And, as he found out last year, the moment he spills a drop, someone is ready to seize on it as a sign that he’s losing his grip. How many other figures in cycling are attempting to do so much? It raises several questions. How does he cope and what drives him on?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Ruffling feathers

There was a perception, during Team Sky’s first season, that Brailsford and his closest colleagues had attempted to redesign the wheel. Feathers were ruffled by their declarations that they were going to look at every aspect of professional cycling and see if certain things could be done better. In the end it seems everyone – including rival team managers – concluded that Team Sky was just like the rest except they had a more expensive bus. But was that an unfair assessment?

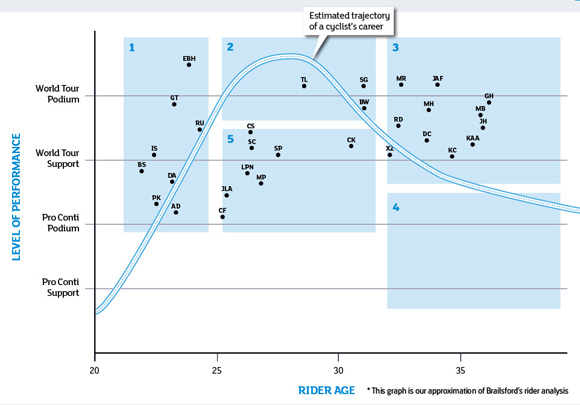

Take his approach to team-building. During a meeting at a Heathrow hotel in December, Brailsford had sketched out a diagram on a napkin to explain to us how the riders for Team Sky’s debut season had been selected. Now, when asked to expand on his theories, he seems at first reluctant but looks through the folders on his computer’s desktop until he finds what he’s looking for. It’s a Powerpoint presentation, a series of graphs with bell curves marking the trajectory of a professional cyclist’s career and a series of dots that roughly equate to each of the riders’ current status [See graph, bottom].

Brailsford seems happiest when he’s studying a graph or analysing some statistics. Taking in the information, identifying the flaws and limiting factors, coming to a conclusion and seeing how he can apply what he’s learned to a practical problem. He spends hours looking at the Cycling Quotient website, cqranking.com, studying results. A cycling fanatic has created, in his spare time, a more effective ranking system than anything the UCI has come up with in the ProTour era. “It’s on my favourites and I look at it every day,” Brailsford says. “There are some flaws in it. For example, a rider will get the same amount of points for a sprint win as another rider will get for a summit finish but they are very different challenges. When you look at the rankings, Cav [Mark Cavendish] has 1,400 points and Hesjedal has 1,200 points but they’ve won them in completely different ways. As riders they don’t overlap at all.

“There are things you can’t tell from statistics but it’s useful as a guide. The site tells you how many days a rider has raced, how many kilometres they’ve raced. The ranking system tells you more than the UCI’s ProTour ranking. It’s the best source of information in pro cycling at the moment. You can see how many points a rider wins per kilometre raced, which is an interesting little fact.”

And Brailsford is off, reading out numbers, analysing. “Take Edvald [Boasson Hagen]. At Columbia in 2009, he was getting more points per day of racing than he did with us last year, but not by much. In 2009 he won Ghent-Wevelgem. Last year he missed the Classics because of injury. So you can’t just look at the stats, you have to know the context.”

Bit of a bookworm

Brailsford is a keen student of coaching manuals and books on management technique. A book called Moneyball, written by Michael Lewis, left an impression on him. Moneyball is about Billy Beane, the general manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team. Beane recognised that the way baseball players were assessed by everyone in the game – from coaches and managers, to other players down to the fans and media – was flawed, based on outdated indicators that were a century old. The game had evolved and the ways of analysing a game were so much more advanced, yet the sport still rated its players according to batting averages and runs batted in. Beane drew up new criteria and enabled the Oakland Athletics, one of the smaller teams in baseball, to compete with the big-spending franchises.

“What he did was take a really refreshing, clean review of the standard thought processes that had developed over a period of God knows how long,” says Brailsford. “In baseball, they talk about a player having ‘the full set’ if they are good at certain things but to have someone come in and say: ‘Are we measuring the right things?’ was refreshing. There was also an issue about money and how you spend it in sport. That’s a big factor in the equation. Beane stood back and said he wasn’t going to go with conventional wisdom. Baseball does lend itself fantastically to stats, much more so than road racing, but I do think it’s refreshing that there was an industry where everyone thought in one way until a guy came along and said ‘hang on a minute’.”

Brailsford frequently looks to other sports. He’s spoken to Sir Alex Ferguson at Manchester United about the art of team-building. He is part of a group of performance analysts. “There is a group of guys – Mike Forde at Chelsea, Damien Comolli at Liverpool, they are stats guys – who do a leaders in performance conference I go to,” he says.

All this adds weight to the school of thought that says unless it can be mapped on a graph or demonstrated by statistics Brailsford is not interested.

“People think we’re all numbers here. We’re not,” he says. “Shane Sutton is the least ‘numbers’ person you’ll get. He will work with a rider and he’ll see something that we can’t see. He’ll spot something and we’ll go and have a proper look at it and he’ll be right. It’s as if he’s watching colour television and we’re watching black and white. He doesn’t get that from numbers.

“The danger with numbers is when people think they are being misused. We got to the point in the Beijing Olympic cycle where the numbers became scrutiny. For the team pursuit we’d worked out how much further they would have to travel and how much time they would lose if they rode just four centimetres off the black line. We said: ‘You have got to get on that black line.’ But in the end, they weren’t enjoying it. Every time they got on their bikes they were being scrutinised and they were thinking more about the black line than anything else. One day Shane just said ‘Right, we’re putting away all the video and the rest of it, just go and ride’. The team came out and did a 3-59 and we were away. Numbers are a guide but they don’t govern everything.”

Under the microscope

Scrutiny is something Brailsford had to learn to deal with in the past year or so. Heading the British track team, in the bunker at Manchester velodrome, where everything is in-house, under wraps and under control, was a cosy existence compared to being out on the road with Team Sky. Sometimes he must have wished his Team Sky sleeveless pullover had been a flak jacket. The track squad sticks its head above the parapet half a dozen times a year. Team Sky is always on show. And as its leader, Brailsford found he had to justify his every move.

As the year went on, he began to look as if the world was weighing on his shoulders. No matter how much he insists he was enjoying being with the team behind closed doors, the public persona was beginning to look strained.

Ever keen to play down the negatives, almost to the point of denying they existed, Brailsford says: “I had a lot of high points in 2010, to be honest. Being confirmed to start the Tour de France was a real high point. The thing was, everyone assumed we’d be in it anyway, but I didn’t assume. Logically I thought we should be okay but until you get that place you can’t be sure, so knowing we were going to the Tour was a real good moment.

“When you look at it, we won our very first bike race. Even though it was only a crit in Australia, we won our first ever bike race. That was fantastic. We did well at the Tour Down Under, we won the team time trial at the Tour of Qatar although we didn’t do too well [in that race] after that. Then there was ‘Pissgate’, wasn’t there... Phew. That was interesting.” He pauses. “Last year, it just seemed like everywhere we went…’ He trails off.

You were scrutinised?

“Yeah.”

Did you feel it was unwarranted?

“No. Not really. I think at the time you think ‘Bloody hell… every single thing,’ you know? It is like living in a goldfish bowl.

“What we do here [at the velodrome] is all about winning or losing. You either get a medal, or you don’t. There isn’t any fan engagement, as such. You have a captive audience. Of course, we want to engage with the fans but we don’t do any proactive work. They come and watch and we try to perform. So we just spend our time in here thinking about how to go faster. If a rider isn’t going well, how do we sort it out? That is what occupies our lives.

“So taking that philosophy out on the road… that mentality. Well, we hadn’t really embraced the idea of fans and being out there, accessible, all the time.”

Like the big wall the team constructed around the riders before time trials at the start of the season so they could warm up with a degree of privacy, instead of being gawped at?

“What the hell were we thinking? I know why we did it. If it was here at the track, we’d do that but it was the wrong decision and we didn’t realise it until we got there and we saw it and knew how much of a barrier it was.”

Living in the binary world of wins and losses on the track and then going to the road, where even the most successful teams ‘lose’ more often than they win, must have challenged Brailsford’s beliefs. “HTC were the most succesful team in terms of wins last year. They won 17 per cent of their races in order to be far and away the best team. If a football manager had a 17 per cent success rate his team would be relegated and he’d get the sack. Wins can be few and far between. It is a sport where you ‘lose’, if you like, an awful lot more than you win.”

Which makes it puzzling that Team Sky were reluctant to play up their successes, choosing instead to adapt the pragmatism that has served British Cycling so well on the track. Job done. Box ticked. Move on to the next goal – the next goal being the Tour de France. In a series of mea culpa interviews at the back end of last year, Brailsford and his team leader Bradley Wiggins acknowledged they had placed far too much emphasis on the Tour, almost setting themselves up to disappoint.

After Wiggins won the Giro d’Italia prologue, becoming only the second British rider to pull on the maglia rosa, Team Sky’s celebrations were – publicly at least – muted. When we put that to Brailsford in December he seemed surprised, thought about it, then acknowledged the point. “Yeah, maybe. In the bus, I can tell you were were absolutely overjoyed. We were all hugging. Maybe that didn’t come across.”

“I think myself, Shane, we are driven by not wanting to lose, more than wanting to win. If we win, fair enough, we’ve won, we go on. But losing… We’re not bad losers, we just hate it. It gets to us. I am highly driven by not wanting to lose, so I found that hard to adjust to.

“But for a new team, we did pretty well. Brad had the pink jersey, Flecha won Het Nieuwsblad, we went to Tirreno-Adriatico and won a stage, Paris-Nice, we won a stage, the Dauphiné, Giro. We were chipping away. Even the first week of the Tour with Geraint’s performances, we were alright but then we got into the hills and it felt like we were having to answer a lot of questions.”

He adds: “But it goes with the territory,” in a way that suggests that, perhaps, he wishes it didn’t.

Was criticism from outsiders, people who were not privy to every decision the hardest thing to stomach? “The challenge is we don’t necessarily have time to fully explain everything that is going on. You can’t say ‘no comment’, which at times you might feel like saying. On a personal level, I was caught in a position where I’d like to explain everything. Assumptions were being made on very limited bits of information. Those assumptions are often very wide of the mark but what do you do about it? You just have to take it on the chin, regroup and keep working.”

Trouble at the Tour

The dark clouds rolled in over Brailsford’s head at the Tour. Leading a British team into the Tour de France with a British contender for the podium should have had a happy ending. But even in the spring, it was clear that a few of the pieces of Brailsford’s carefully-assembled jigsaw did not fit properly. There were changes at management level and after the Classics, Brailsford found himself short-handed to the extent that he and Sutton had to get out to races and run things on the ground, which was never part of the plan.

Scott Sunderland’s son was diagnosed with a serious illness and he stepped away from the team. Talk to enough people and you get the very strong sense that Sunderland’s face didn’t fit anyway. Brailsford refuses to be drawn. “We made a statement at the time, which I’d stick to. I think it’s important to talk about the guys we have got now and look forward. We’ve got a good bunch of guys, it’s well structured, there’s a lot more clarity in roles and responsibilities and how communication works.”

It means Brailsford is able to get out of the team car and get back in the position he always intended to take. “I am comfortable in a room getting a group of people together to thrash things around so we know where we’re going. The greatest danger for me is that I am a bit of an orchestra conductor. If I think the violinist isn’t quite in tune, the worst thing I can do is grab the violin and say ‘this is how you do it’, play a little tune which probably isn’t any better and hand it back. I’m not going to make things better and that person is going to feel totally undermined. When I see something not working, I find it very hard not to dive in. So when I was at the races, I found I got caught in the 24 hours that you are in and it just keeps rolling along. You want to get out of it and start looking at the medium term but unless you stop and come up for air you’re almost trapped.”

Once the season ended, Brailsford re-evaluated, although the questions haven’t entirely gone away. There’s still the issue of Floyd Landis’s allegations against Michael Barry to be resolved. Brailsford has answered the question several times since last May and the answer has been the same. He’s not going to change it until something changes.

Before our interview, he expressed frustration at the way an interview he’d done with The Guardian had turned out. The interviewer asked a question that suggested that Sky had dropped its zero-tolerance policy with regard to hiring sports directors. Brailsford did not pick up on the point and clarify it in his answer. The story portrayed Team Sky as having dropped its ‘zero-tolerance policy’. And in the echo chamber that is the modern media, that line – a line Brailsford had not actually said – became the story. He shrugs. “I had a word with the reporter and he admitted I hadn’t said it,” he says. “They printed the full transcript of the interview so people can see what I said. Nothing has changed here. Our policy hasn’t changed but it’s out there now. What do you do?” It was tempting to suggest that a year or so ago, Brailsford would have internalised it and let it fester away but now he seems more sanguine.

Time to unwind

How does Dave Brailsford switch off and unwind? “I ride my bike. I like riding my bike. I know this is going to sound horrible but there’s very few people I like riding my bike with. I like riding with Shane. I really enjoy that, even though he batters me. That’s quality time.”

Do you talk shop?

“Oh yes. We always do, really.”

Do you ever not talk shop?

“No. We talk things over. When you’re on the bike you get time to think and that’s important to me. If you can get an hour-and-a-half in in the morning you feel better about yourself. You feel like you have done something for yourself.

“The number one thing would be to spend time with my daughter. She’s six. I have a step-daughter who is 21 and she’s just had a baby, so I like spending my time with them.”

What would you do if you found yourself with a couple of hours to spare? “If my daughter had gone to bed and I’ve got some time, I’ll pick up my computer and do something cycling-related. I’ll read stuff, I’ll trawl through cqranking. It’s like a hobby. No, actually, I’ll take that back. It’s a passion.”

So the answer is, Dave Brailsford never really switches off from work…

“It’s not work though is it? For us. It’s not work. We live life on the road. We’re consumed by it.”

Running British Cycling and Team Sky means that Brailsford is in charge of dozens of people but who does he consider he works for?

“First and foremost, I work for the riders. If there’s something that needs to be done to help any of the riders, I will do it, even if it means staying up half the night. That is what drives me. The coaches too. Is there anything I can do to help Yatesy or Rod or Bobby do their job better? That’s my role, not to get in the team car and start giving Sean tips.”

What type of person thrives in a Brailsford-run organization? “Guys who take responsibility. Guys who will talk about ideas and they’ll put their spin on it and come back with something of their own. I like that. People who don’t need their hands holding. People who aren’t scared to speak the truth. People who don’t want to go with conventional wisdom all the time. People who are open, honest, people who have passion.

“The thing is, there are constantly things going wrong. Every day. If people are coming up to you with problems all the time, they’re not going to last too long. If people just want to moan, that doesn’t chime very well. I hate moaners. But I don’t want people who are overly optimistic either.

“You can write as many mission statements as you like but what you want is people who are on a mission.”

***************************************************************************************************************************

TEAM BUILDING WITH DAVE BRAILSFORD

For a hi-res pic of the graph, click here.

Please note, this graph is our interpretation of Dave Brailsford's theory, not the exact graph produced for Team Sky

“The graph roughly maps the trajectory of a cyclist’s career,” says Brailsford. “There are different phases of a pro’s career. As people go from phase to phase, what does it mean in terms of potential, salary, the coaching and support you need and lifestyle?

“As a youngster all the riders can think about is turning pro. That is all they can see and it drives them forward. Then they get their pro contract and they want to get their first win. That continues until they win a race, then they start to confirm it and get more confidence. When they get to the top they want more money, money, money – they want to be paid the same as their mates.

“We have split the phases, broadly speaking, into riders who can support in Pro Continental races, riders who can podium in Pro Continental races, riders who can support in World Tour races and riders who can podium in World Tour races, who are your top guys.

“For the older guys the aim is to try to flatten out the curve so that they can continue performing at a high level for longer. Your guys like Brad, Mick Rogers, Flecha.”

1. The guys on the left of the chart are being paid for what we believe they can do in the future. It’s quite difficult but people gamble. Someone like Edvald is obviously a great talent. It could be unbelievable if he goes on to fulfil all that potential, or it could be that he doesn’t quite. But you’re betting on the future.

You want to concentrate your coaching on these guys. They are your future. We found that last year, we probably didn’t give these guys – the likes of Swift, Stannard, Kennaugh – everything we could because of the challenges of setting up the team. Also the sickness at the Vuelta meant they missed out on the goal they had been working towards.

The key here is to get people who are ahead of the curve – performing at a higher level for their age. The ideal scenario is that they outperform their salary. A great example would be Richie Porte at Saxo Bank. He was seventh at the Giro as a neo-pro but there were guys who finished much lower than that getting paid a lot, lot more.

This is the area we want to invest in. We hired Alex Dowsett because we believe he has a lot of potential and he had a super season. We looked at Luke Rowe but felt he needed another year in the [British Cycling] academy. Rigoberto Uran has come in. He’s a young rider but he’s been around a while. He’s punchy so he gives us something we didn’t have, which is a rider for the Ardennes. This is where we concentrate our coaching and development.

2. These are your top performers. Guys who can deliver big results and who are in the peak of their career.

3. These guys are getting older now but if they can still do a job they still deserve their place on the team. Guys over here don’t need coaching, as such. They still need support but we are not developing their talent, we are prolonging their careers.

4. Once you get down here, it’s time to say goodbye to the guys. Is it worth having an older guy, with his salary expectations, who can podium at Pro Continental level but not at the bigger races? Probably not.

5. Riders in this area are borderline for us. As you get older, the potential for improvement disappears and so it’s much more a judgement call. A rider might bring something to the team in terms of his personality that makes him a good guy to have around.

This feature first appeared in Cycle Sport May 2011, which is on sale until April 19th in the UK, later in the US.

Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/cyclesportmag

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.