'It was really radical': The Giant TCR escaped a UCI ban, and is still going strong

Giant’s signature bike changed the look of road bikes forever. Adam Becket looks back on what the TCR has meant for bike design

With the new Giant TCR launched this week, we thought it was time to look back at the history of the revolutionary bike.

This feature was originally published in the 29 December 2022 print edition of Cycling Weekly magazine, all interviews were conducted at this time. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered to your door every week.

There are moments in design history when something is developed which changes the face of technology as we know it. There are cars like the Volkswagen Beetle or the Mini, and planes like Concorde or the Boeing 747, which stretched the boundaries of what these methods of transport could be, taking things on by years.

Bikes are no different. Ever since the early days of bicycles, especially once they began to be raced, there have been design moments when a huge change has occurred, and evolution has given way to revolution. There was the Legano Team Bike ridden by Gino Bartali in the 1940s, the first to be fitted with a derailleur, which allowed riders to switch gears on the go. After this, there were incremental changes, with different materials being employed, aluminium and carbon fibre being the biggest differences, but bikes were largely the same shape.

The classic straight-lined triangle of the frame was the standard, with all road bikes looking very similar. In fact, most bicycles looked the same, from the one used by your local postman to top professionals.

Then, along came Mike Burrows [who died in August 2022]. The Norfolk designer, having spent years in cycle design’s hinterlands with monoblade forks, micro lo-pros and blobby monocoque frames, which were all regarded as too eccentric for the conservative world of road cycling, finally received mainstream recognition after Chris Boardman won the individual pursuit at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. This was on the Lotus bike that Burrows had originally created.

With that design validated, he found himself in demand and was snapped up by the Taiwanese brand Giant, which already by the mid-Nineties had become one of the world’s largest bike manufacturers.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The man from East Anglia convinced Tony Lo and King Liu, Giant’s owners, about his concept for a new road bike design, which was then called compact road design. It was revolutionary. Instead of the horizontal top tube, a sloped one was introduced, which allowed for smaller frames. This led to it being stiffer and lighter too; in 1997 the Total Compact Road was born.

Burrows had always complained about there being too many different sizes of traditional road bike frames, looking enviously at mountain bikes, which usually came in three different sizes, instead of 10 or more. With angle adjustable stems in only three sizes, a bike could be easier to set up for different positions.

Essentially, the sloping top tube design reduced the weight of the frame and the smaller rear triangle increased the stiffness, and each size would suit a bigger range of people than traditional road frames.

Take a look at your road bike now, and you’ll likely see the TCR’s influence. Unless you have a specialist frame, you will probably have a sloping top tube to a greater or lesser degree, that traces its DNA back to that original model.

Revolution in the shop

For Bristol mechanic Paul Meadows, who has been working on bikes in south west England for a few decades, the difference was enormous. There was no more measuring bikes for customers by hoisting up the horizontal top tube underneath your legs, but instead a few frames that fitted everyone, with adjustable parts.

“The main thing, obviously, was this small, medium and large way of looking at bikes, which with the drop top tube design was pretty special at that time,” he told Cycling Weekly. “Even at the time there was a fair bit of controversy, and a lot of people were stubborn, saying it's not a proper way to build bikes. The horizontal top tube was the traditional layout and design.

“From the manufacturers point of view, it's hard to know really whether the true vision was just to save money or whether it was the aero benefits.”

In a way, it didn’t matter, because it did both; the smaller frame, with particular stems added, could even allow the frame to be adapted with a time trial set-up back in the days when a lower front end was the simple TTing aim.

“It benefited shops, because you only had to get three bikes from a range,” Meadows continues. “Then you had the whole range of stock, whereas previously, you might have had to have five, or maybe even six. From that point of view, it made a massive difference. And also for getting spare parts and stuff. It's just there's three frames, if one breaks it was not hard to get the parts.”

Revolution on the road

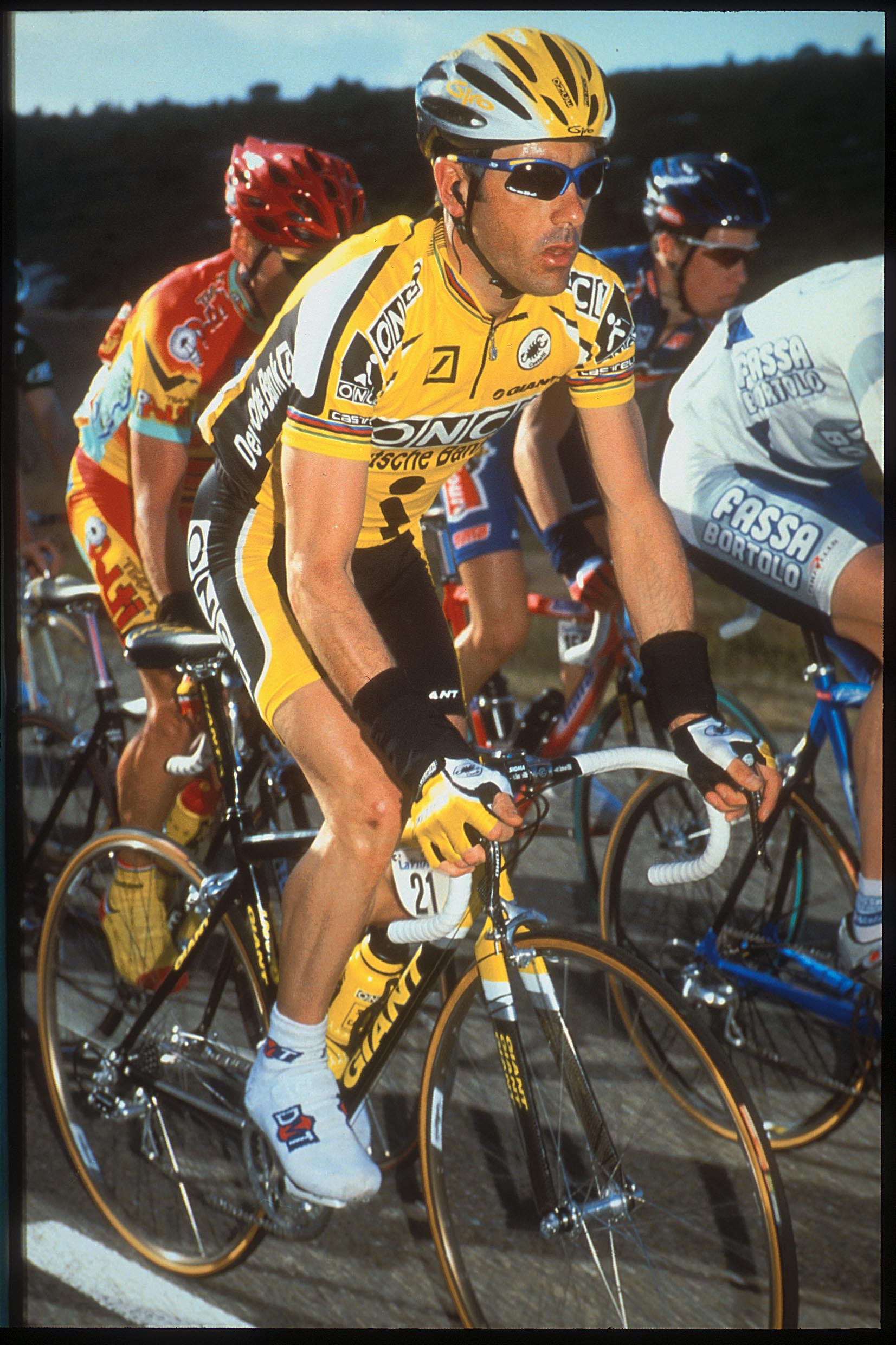

It changed things on the professional racing scene too. The first elite team to ride the TCR were ONCE, with riders like Laurent Jalabert and Abraham Olano riding the machine.

While the rest of the peloton toiled up climbs on their conventional machines, ONCE attacked on their spiky yellow-and-black TCRs like a swarm of wasps. In team time trials the squad was unbeatable, and the riders racked up wins in road races too.

Of course it is difficult to know exactly where the TCR’s influence ends and the team’s string of doping scandals begins, but the high profile wins did lead to cycling’s governing body, the UCI, objecting to the design, with the geometry being deemed too radical. It had begun to be popular, despite looking so different, due to it winning races on the global stage, but it might have pushed things too far.

However, following a meeting between Hein Verbruggen and his fellow Dutchman Jan Derksen, the boss of Giant Europe, every new road bike design was influenced by the TCR.

In the second year of its existence, the TCR was ridden by the British Harrods team, who had Matt Stephens among their number. The rider turned pundit remembers he and his teammates being puzzled at first by its difference, but quickly became used to it. Used to it so much that he became British national champion on it in 1998.

“It really was radical,” he says. “We were sponsored by the cycling shop franchise within Harrods, so we had the TCR and the MCR [the monocoque TT bike, also designed by Burrows] too. When we first got them, they were totally different. We didn't know what sizing to have, and I remember saying that it looked too small. It had a bladed seat pin, which was super cool. I went for a slightly smaller frame with a ridiculously long seat pin.

“The thinking behind it was all about the additional control you get on a smaller frame, looking at BMX and mountain bikes. The sloping top tube was different, which has never really gone away. We also had the adjustable stem which came with it on a ratchet system. You could essentially turn the TCR from a road bike to a TT bike by changing that.

“It was radical on so many different points,” he continues. “I had a great year on that bike. To win the nationals on it was pretty cool, but when you look at the riders that were using it back then, they really did hit the ground running. It was a bit of a head turner.

“Coupled with the fact we had custom paint jobs, for Harrods, gold with green logos on them, everything about them was pretty cool. It did feel very special, but fundamentally, it was a very comfortable, agile bike to ride. It was fundamentally cutting edge. It was a really lovely bike to ride, and the adjustability was great too. I have nothing negative to say about it.”

Continued love

The TCR went on to be used by T-Mobile in the mid-noughties, then Rabobank, and eventually the eponymous Giant-Alpecin. After sponsoring the late CCC team, Giant and the TCR returned to the WorldTour with BikeExchange-Jayco at the beginning of 2022.

The radical bike has continued to be adored by those who have ridden it, from those winning the biggest races to ordinary consumers.

Billy Cheetham, the manager of Giant’s store in Leamington Spa [at time of publication], is quick to point out the maintained popularity of the Tawianese brand’s climbing bike.

“A lot of people go for it because it goes into corners like it's on rails, climbs extremely well and so it's a very versatile, all round bike. It ticks all the boxes,” he explains.

The pros of course don’t get a choice but today’s riders are still impressed. Simon Geschke, the veteran Cofidis rider, spent seven years on the machine with Giant-Alpecin and then with CCC. It was while he was on the team that Tom Dumoulin won the Giro d’Italia on it, the last Grand Tour the TCR has won, to date.

“It was my favourite bike for a long time,” Geschke says. “It is a really nice bike, especially the last one I had with the disc brakes. It was super stiff and light, I remember the mechanics had to put a bit of weight under the saddle because it was under the UCI limit. It was 6.8kg, but the mechanics were afraid that there would be 50g missing when it got weighed, maybe the scales wouldn't be calibrated properly. So they put a bit of weight on it to make it 6.85kg.

“I won the stage of the Tour de France on that bike, so I have good memories.. It got a little bit behind when the aero bikes came into the peloton, then you could see the disadvantage sometimes because it was light and stiff, and I really liked the handling, but when I was behind a few other guys with aero bikes, then I felt the aerodynamics were not so good on the flat. But you see the company is very innovative, they built the new Propel with some of the DNA from the TCR, so that's a new dynamic, a super light aero bike.”

It continues to win things, and influence other bikes, 27 years on from its inception. It hasn’t finished yet.

Adam is Cycling Weekly’s news editor – his greatest love is road racing but as long as he is cycling, he's happy. Before joining CW in 2021 he spent two years writing for Procycling. He's usually out and about on the roads of Bristol and its surrounds.

Before cycling took over his professional life, he covered ecclesiastical matters at the world’s largest Anglican newspaper and politics at Business Insider. Don't ask how that is related to riding bikes.