The Mur de Huy: where La Flèche Wallonne will be won or lost

The Mur de Huy is one of the steepest and most spectacular finishing climbs in cycling. With its continued presence in the Flèche Wallonne, we have a look at this famous climb

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“The last climb of the Mur is everything. It’s just 1,300 metres of road, but when I won, that road went on for ever, especially the last few metres. I never felt such pain and ecstasy at the same time,” Mario Aerts, Flèche Wallonne winner in 2002.

Huy is a small, fairly non-descript town that straddles the Meuse river, deep in a fold of the Ardennes hills in southern Belgium. Not much happens here, and there’s not much to see. Except that it is the location of the Mur de Huy, the steepest finishing climb in cycling.

>>> The climbs of Liège-Bastogne-Liège

The Mur de Huy has given shape and character to La Flèche Wallonne, a tough race, a Classic with a list of distinguished winners, but a race that used to suffer in comparison with Liège-Bastogne-Liège. That changed when the Mur was included.

>>> La Flèche Wallonne 2019: all you need to know

Flèche is younger than Liège. The first edition was run in 1936, but for years it had no identity other than that of a race in the hills between Liège and Charleroi. Sometimes it went east to west, sometimes west to east. It was always hard, always prized among the fans and by those who won it. And it satisfied the thirst for bike racing of a huge Italian community that worked in the steel mills and mines of the Meuse. But until the potential of the Mur de Huy was discovered, Flèche lacked a defining shape.

Today Flèche Wallonne starts in Ans, before winding through the hills of the Ardennes. Then the race begins to build like a symphony, drawing intensity from three ascents of the Mur that come in quickening succession as they count down towards the end. The finale of Flèche - a gut- wrenching haul up the brutal climb to the finish line at the top.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

It’s a winning formula, and every great race has to have one. Just think of them; the Capi, Cipressa and Poggio of Milan-San Remo, the bergs of Flanders, the cobbles of Roubaix, the saw-tooth run north from Bastogne to Liège, and the lakeside climbs of Lombardy. That familiar geography, repeated year after year is something we can understand, compare and trust.

First ascent

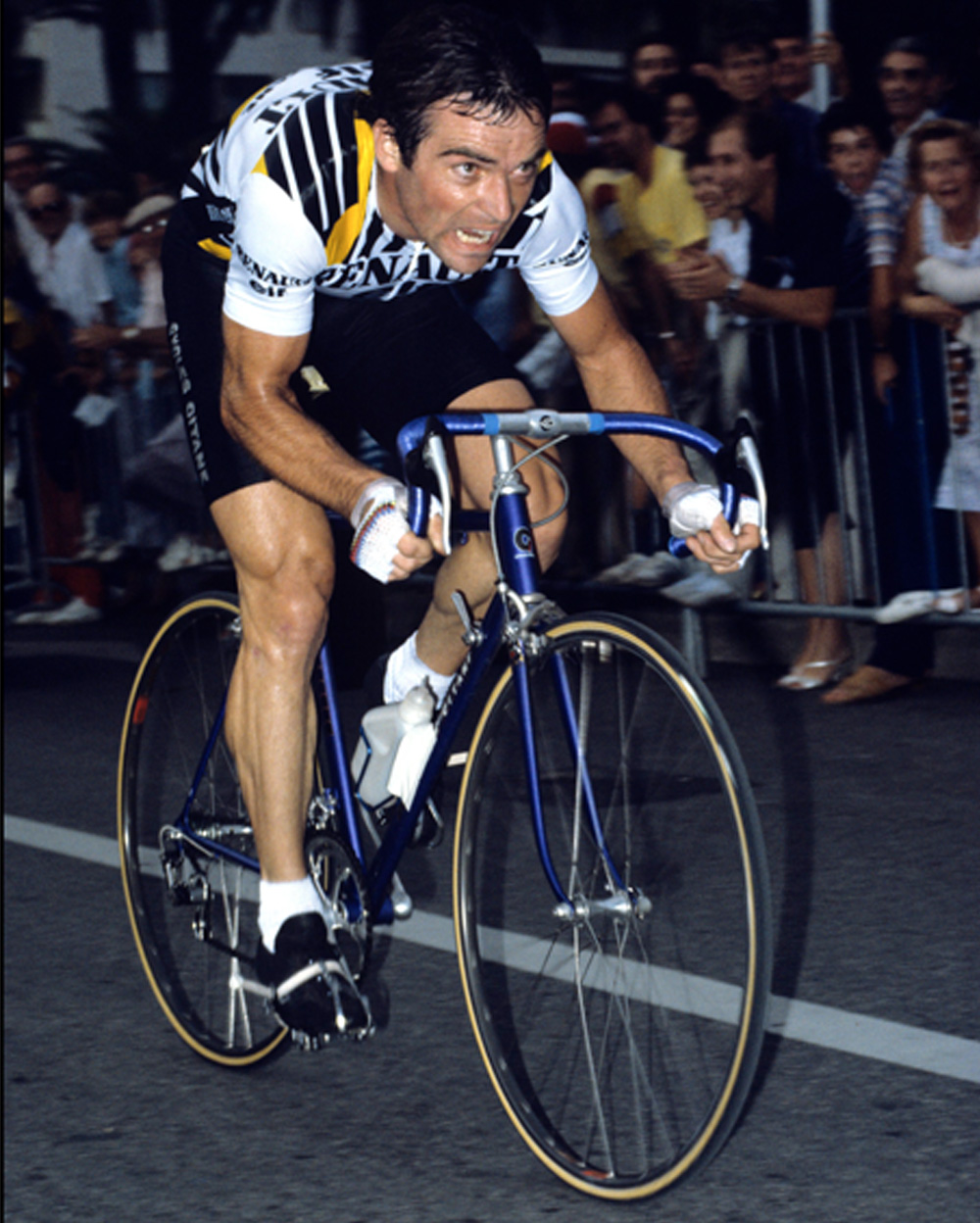

The Mur de Huy first hosted the finish of Flèche Wallonne in 1983, and it debuted in style with victory by Bernard Hinault. Brutal is a word used often in cycling, but there isn’t a better one to describe the Mur. The south side of the Meuse valley is incredibly steep in Huy, so steep that they built a cable car that goes up roughly parallel with the Mur. The main roads in Huy all steer well clear of this slope before resuming their original course.

The climb’s steepness has riders searching for their biggest sprockets. In 1994 Britain’s Brian Smith rode Flèche and he remembers the Mur de Huy well: “I had 39x25 on my bike because it was as low as you could go, but I heard riders this year were fitting 39x27.”

In Hinault’s day it was 39x23, but he probably didn’t use that, at least not all the way. He went through a phase of using big gears in the early eighties. Riders who trained with him remember that he hardly ever came off the big ring.

Hinault was influenced by a coach, Claude Genzing and together they felt that the accepted cadences of cycling were too high. Hinault was one of the first to use a 12 sprocket, and their beliefs were backed up by sports scientists at the time who cited rowers, swimmers and even some distance runners as having lower cadences than cyclists. Knee problems kept Hinault from riding the Tour de France in 1983. Who knows if grinding up the Mur exacerbated the problem?

Times and beliefs change. Modern riders understand the benefits of low gears on ramp-like climbs such as the Mur de Huy. If nothing else they make the killing accelerations of the ‘Masters of the Mur’ even more telling. Moreno Argentin, with three victories and Laurent Jalabert, who had two, both possessed fearsome sprints. Argentin and double Flèche Wallonne winner, Claude Criquielion also won the Tour of Flanders, another race which suits explosive riders.

The Mur de Huy isn’t a climb where a rider can slowly grind away the opposition, like Cadel Evans tried to do in 2008 and 2009. This is all the more true since Flèche Wallonne is at least fifty kilometres short of being a Monument, which means that there are more riders left in at the kill.

Deceptive start

The Mur de Huy is prodigiously steep, but it has a deceptive start. Down by the river, just as the Avenue de Condroz becomes the Rue de Marche, the climbing begins at seven per cent. After 100 metres it flattens out to almost nothing, then rises again at five and then six per cent. It‘s tough but it’s just a taster of the horror to come.

That begins as the route flicks right from wide main roads into the Chemin des Chappelles, so named after the seven chapels that stand along its length. There’s no time to offer up a prayer, as the sensation of climbing switches in the legs from just about tolerable to absolute pain. A road sign says 19 per cent, for what reason we are unsure as 19 is neither the average gradient nor the steepest part of the climb. Still, the sign isn’t good for morale.

The first steep section is straight and averages around 11 per cent. A right and left bend maintain the gradient, then as the road straightens once more the terrible truth of this climb comes into view. Huy, Huy, Huy, mock the white stencilled letters on the road. As if a location fix was necessary at this stage. The vicious S-bend that is the crucial part of this climb comes into view now, the Mur de Huy's equivalent to the Eiger’s White Spider.

Kim Kirchen, the winner of Flèche in 2008 reckons that the S-bend is where most riders get the Mur wrong.

“You have to be in the first 15 to 20 at the beginning of the climb, otherwise you can’t win at all. But after that it’s about waiting, and you have to have something left for after the S-bend. If you are on the limit there winning is impossible. Also, because the finish is so close by normal standards some riders who might have something left will panic and go harder than they need to. That’s good for the rest, because they stretch it out and you don’t get boxed in,” he says.

It’s easy to understand why riders get it wrong, just making it around the 25 per cent gradient of the formidable S-bend requires a huge effort, and one that is very difficult to judge. The crowd is particularly thick here. It is the crunch point of the entire race, 199.5 kilometres boiled down into a few metres. Excitement spills over, but Flèche winners always keep their cool here, always dose their effort around the bends to perfection. The S-bend is a filter that grades everyone ready for the final push.

Winning formula

As the formula of three circuits of the Mur developed, so has the whole shape of La Flèche Wallonne and the way it is won. Teams now know to wait for the last ascent of the Mur. That isn’t because modern riders have lost their sense of adventure, it’s just that a big Merckx-like exploit won’t work any more, not in this race.

Not in many races for that matter. Former CSC directeur sportif Scott Sunderland explains why. “There are bigger groups at the end of all the Classics for a number of reasons, but none of them are because the races are easier as some suggest, because they aren’t.

“Everybody knows what each other is doing nowadays. Training information and research is all out there and available, and there is so much skill in preparing riders properly. No one has their secret gurus or trainers anymore. Even the fact that most of the bikes pros use are made in a couple of factories in Taiwan make cycling a much more level playing field today. That’s why there are more riders in at the kill.”

Cycling has changed a lot, and modern tastes seem to require identifiable formulae like the one Flèche Wallonne has. Modern winners have adapted to that fact. The S-bend lasts no more than 40 metres, then the gradient relaxes a bit, but not much. The road curves gently away to the left for 300 metres of around 14 per cent. This sweeping bend acts as a cue in the race’s script to the potential winners. At last they can make their moves.

The trick still seems to be to avoid hitting maximum until as late as possible. But by now there are only a few left in the race who have not fired off all their bullets. The Huy, Huy, Huy road markings continue their exhortations along the final section. On the left of the road is a short terrace of stone houses, the first a house-height below the last, their front steps mark out the gradient. On the right is a cobble path and roadside shrine, just in case seven chapels are not enough.

Then suddenly the black wall of tarmac that has been the rider’s focus all the way up the climb is replaced by blue sky. The last chapel rises into view on the right. The top has come. The world comes back into view after being nothing but a tunnel of pain since that 19 per cent sign way back down the hill. The Mur is done, it’s over. At last.

Riders of the Mur

Kim Kirchen

Never has a sprint to the top of the Mur been so well timed as Kim Kirchen’s in 2008, nor so knee-grindingly agonising.

In teeming rain, Kirchen watched as Cadel Evans went for it with 400 metres to go. Evans’s attack was strong, but Kirchen sat in the wheel of Davide Rebellin (who won in 2009 before his victory was tarnished by news of a positive test from Beijing) and bided his time. With 300 metres to go, Kirchen incredibly shifted up to his big ring and started his own push for victory. As Evans faded, Kirchen put his nose in front in the final 200 metres, then he surged past. Evans had mistimed his effort, and Kirchen ground clear to take his biggest ever victory.

“I chose to stick with Rebellin because he’s never in the wrong position,” Kirchen told Cycle Sport.

“Evans’ tactic was to ride evenly all the way, but he didn’t quite have enough to stay clear to the end. I decided to go steady almost all the way to the top, but then give it everything in as big a gear as I could from 300 to go. It was a beautiful moment.”

Moreno Argentin

The dapper Venetian held the record for victories in Flèche until Rebellin equalled his 1990, 1991 and 1994 victories (Alejandro Valverde now holds the record with five victories). But maybe Argentin’s back-to-back victories are more impressive.

His 1990 victory did come at the expense of chasing down a brave lone bid by Robert Millar.

Millar had built a steady lone lead when Gert-Jan Theunisse instigated a counter attack shortly after the Côte de Ben-Ahin. He was quickly joined by Miguel Indurain, Steven Rooks, Raul Alcala Stephen Roche, Davide Cassani, Argentin and the 1987 winner, Jean-Claude Leclercq.

It took them 12 kilometres but the group caught Millar on the descent into Huy, where Argentin used his team-mate Cassani to control the group, until he extinguished any hope the others had of victory by galloping away with 200 metres to go. It was a textbook demonstration of how to win on the Mur.

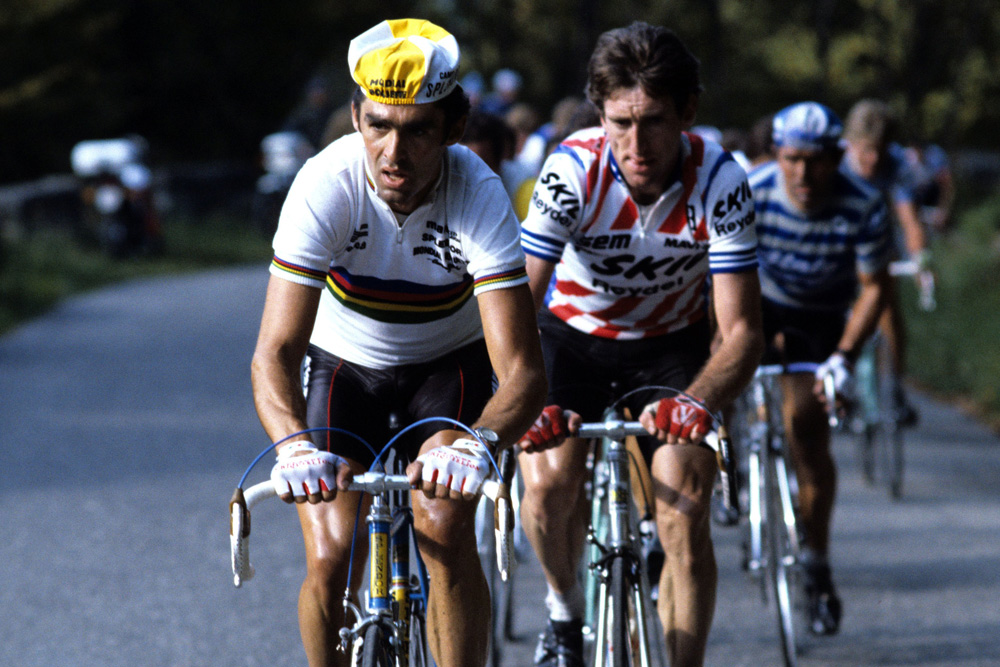

Claude Criquielion

Not only was Criquielion Belgian, he was a Walloon, a French-speaking Belgian. Criquielion came from Deux Acren, eight kilometres south of Geraardsbergen and two kilometres on the French-speaking side of Belgium’s Taal Grenz (the language border). However, his home region is nothing like the Ardennes. It’s a tongue of land, called Hainaut, to the west of the real Wallonia that whoever formed Belgium decided to stick out at Flanders.

The people of Hainault are all bilingual, and Criq’s cycling skills straddled the border. He was world road champion in 1984, Belgian champion in 1990 and won the Tour of Flanders in 1987 to go with his wins in the 1985 and 1989 Flèche Wallonne.

Laurent Jalabert

Another double winner on the Mur, Laurent Jalabert took victories in the 1995 and 1997 Flèche Wallonne. He started his cycling life as a very good sprinter, but suffered a bad crash in the Tour de France. When Jalabert came back he had flowered into an all-rounder with a leaning towards the Classics.

The Mur de Huy was perfect for Jalabert. His 1995 victory in Flèche was particularly good as he outsprinted a similarly talented rider in Maurizio Fondriest, who had won the race in 1993. A few days later Jalabert took fourth place in Liège-Bastogne-Liège.

Alejandro Valverde

If anyone has mastered the formula of Flèche Wallonne, it's Valverde. The Spaniard holds a record five victories, dominating the race with four consecutive wins from 2014 to 2017, much to the exacerbation of his rivals.

Valverde won Flèche for the first time in 2006, but had to wait eight years (including a year out for a doping ban) to really find his footing on the Mur.

But since then, the 37-year-old makes tackling the climb look essentially quite easy. With rivals attacking and falling away exhausted around him, Valverde simply has the knack of waiting, waiting, waiting, before using his trademark kick to leave everyone behind in the final 100 metres.

Such is his dominance in Flèche that other riders have suggested they'll have to wait until Valverde finally retires to have a chance at adding it to their palmarès.

Marianne Vos

Marianne Vos has secured five wins atop of the Huy, over the course of a seven year period. Her first win was in 2007, and the last in 2013.

Being a power athlete with a slight frame, Vos is perfectly positioned for victory on the steep slopes of Huy. Her first victory, now over a decade ago, saw the then 19-year-old deny Nicole Cooke a fourth victory by surging past the British rider's attack.

The last time Vos raised her hands on the Huy, she pulled away from decorated climbers, Elisa Longo Borghini and Ashleigh Moolman Pasio.

Since then, the multiple time world champion has struggled with illness and injury. However, the return to form seems almost complete after a win at Women's World Tour race Trofeo Alfredo Binda and third place at Amstel Gold Race already this season.

Anna van der Breggen

Dutch rider Anna van der Breggen has claimed the last four consecutive victories of La Flèche Wallonne Femmes, on three occasions spring boarding from the demise of a team mate's break.

In 2018, Van der Breggen was part of a bunch which caught a four rider escape group, including Boels-Dolmans team mate Megan Guarnier. The catch was made with 200 metres to go, at which point Van der Breggen attacked to sprint clear, taking the win by two seconds.

One year before, in 2017, she again caught a break of two - this time containing team mate Lizzie Deignan - on the lower slopes of the Huy, before sprinting on to win solo, 16 seconds ahead of Deignan.

In 2016, riding for Rabo-Liv, Van der Breggen broke away from a leading group of seven over the penultimate climb. Evelyn Stevens (Boels-Dolmans) went with her, with the Dutchwoman proving herself the strongest of the two on the Huy, whilst Megan Guarnier rounded off the podium, finishing 22 seconds later.

The first win, in 2015, came after Van der Breggen bridged to team mate Raxane Knetemann, and Annemiek van Vleuten (then Bigla), making the catch at the foot of the climb and charging onwards to win 12-seconds ahead of Van Vleuten.

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast