How Italian cycling is still in Marco Pantani's shadow

Sixteen years after passed Marco Pantani’s death and more than 20 since he was in his pomp, Peter Cossins examined his shadow over Italian cycling, which has been in a state of steady decline

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This feature originally appeared in the 21 May 2020 issue of Cycling Weekly, an Italian racing special. We're reproducing it here on what would have been Marco Pantani's 52nd birthday.

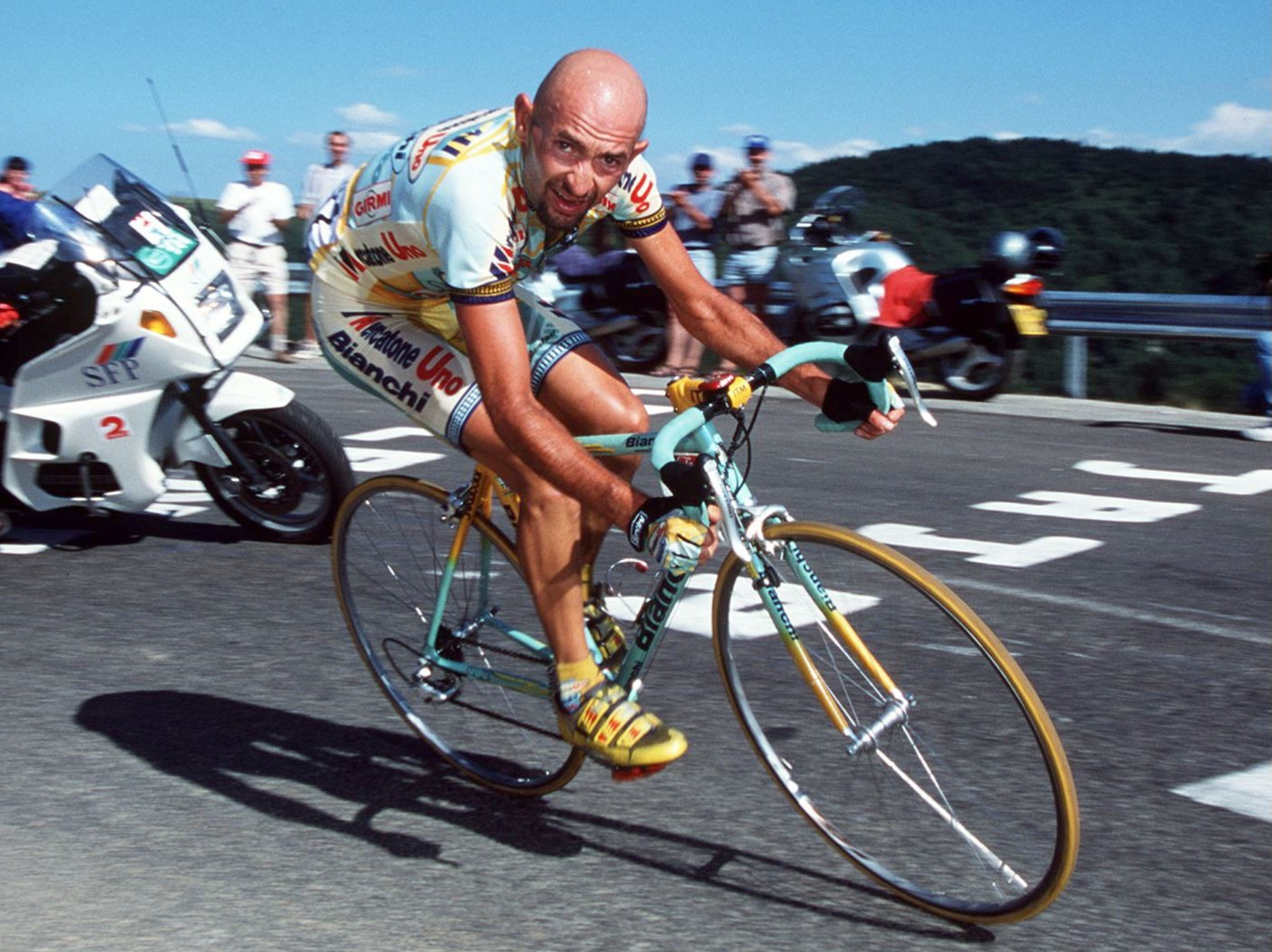

On one side of the door the light is golden and vibrant, the glow provided by Fausto Coppi, Gino Bartali, Felice Gimondi and so many other legends of Italian cycle sport, their exploits captured in grainy black and white images. On the other side, it’s much darker, the gloom heightened by the Nosferatu-shaped shadow cast by the figure in the doorway, elfin, a bandanna covering his bald pate, a large earring hanging from each ear, very much living up to his alter ego, ‘the Pirate’.

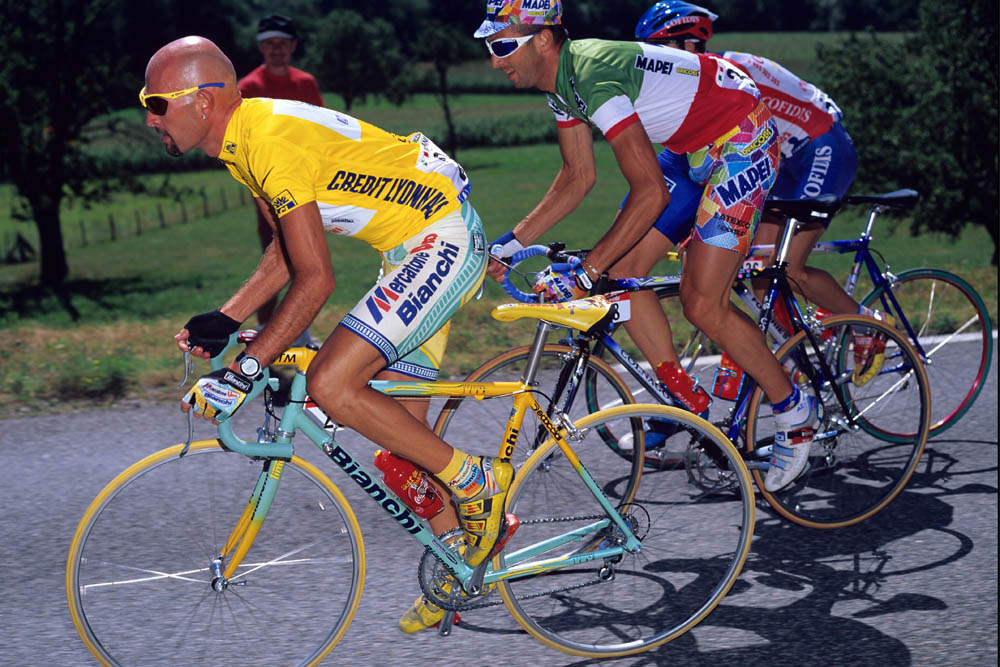

This is the picture that is generally painted when analysing the fortunes of Italian cycling following the death on Valentine’s Day in 2004 of Marco Pantani. When he was in his pomp in the mid-1990s, Italian cycling was still surfing a wave of popularity that had carried it from the first years of the 20th century. In 1998, when Pantani claimed the first leg of the Giro-Tour double, no fewer than 13 Italian teams lined up in the corsa rosa, while half a dozen Italians representing six different squads finished in the top 10.

Fast forward 21 years to the Giro’s latest edition, and the comparison is stark: just three Italian teams on the start line, each of them present thanks to a wild-card invitation from the race organiser RCS, and just one Italian finisher in the top 10, almost inevitably Vincenzo Nibali, the nation’s unquestioned standard-bearer for the past decade. Yet, despite victories in all three Grand Tours as well as both Italian one-day Monuments, the Sicilian has failed to evoke the same interest and fervour as Pantani, who has become a mythical figure, one who has been lionised for feats that are remembered by memorials on the climbs where he shone brightest.

“We must ask ourselves why we still talk about him,” mused former La Gazzetta dello Sport journalist Marco Pastonesi following the publication of his book Pantani era un Dio (Pantani was a God). “We still talk about him because he was the last to provide real emotions. There is still talk of him because he was physically ugly, small, hairless and clumsy on a bicycle and he won. Alone against everyone. There is still talk of him because during his career he had many injuries and accidents and he always came back, and as a winner. Until that moment when he finally failed to get back up.”

This analysis may seem overblown, but Pastonesi is one of the most astute observers of the Italian cycling scene, and it chimes with that of other journalists. “When you go to Italy and get into a taxi or go into a hotel and they ask you why you’re there, when you say you’re there for a bike race they quickly mention Pantani but don’t really have any knowledge beyond that. They’ll say, ‘Yes, I loved Pantani…’ For the lay public as far as cycling goes it’s almost as if the clock stopped on the sport with Pantani,” says writer and podcaster Daniel Friebe.

It is widely agreed that this stoppage occurred not on the occasion of Pantani’s death at the age of 34 on Valentine’s Day 2004, when he was found in a Rimini hotel room, a cocaine overdose causing pulmonary and cerebral oedema, but five years earlier when he was forced to leave the Giro following an elevated red blood cell count just two days from completing a successful defence of his title.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Pantani described his exclusion that day at Madonna di Campiglio as “a plot” and declared prophetically, “I’ve had many misfortunes, but this time I won’t recover.” According to L’Equipe journalist Philippe Brunel, author of The Life and Death of Marco Pantani, the controversy stripped the climber of the personality that he had created to cover over his self-hatred: “He felt that he’d been shunned, abandoned by all those who had loved him.” The result of this, says Brunel, is that Pantani “no longer knew who to be. He had cocaine problems. He frequented a very dangerous world of drug dealers. It was the city of Rimini that killed Pantani, with its poisons, its drugs, the malavita as they say in Italy. He was caught in the middle, in his solitude.”

The man, the legend

The steady mythologisation of Pantani followed. Monuments have been erected in his home town and on the climbs where he scattered his racing rivals, his tomb has become a place of pilgrimage, and there have been songs, poems and numerous books written about him. Some have confirmed the official verdict of suicide, others, including Brunel’s, have touted the possibility that he had been murdered, reportedly on the orders of the Camorra, the Neapolitan crime organisation.

Pantani has been hailed as the last of the old-school champions, a rider who raced on instinct and improvisation, who hated technology whose use was spreading through the sport – although at the same time he was being ‘prepared’ by someone who was right at the cutting edge.

This last point, suggests Friebe, is one of the most significant when it comes to understanding why cycling has fallen so far from its Pantani-inspired peak in Italy. “As much as the Italians were quite ambivalent about doping, and still are to a certain extent, they were turned off by it. For a lay TV audience, it became quite difficult for them to understand what was going on, to understand the talk of haematocrit and other levels. A lot of fans wanted a simple narrative, but their eyes were glazing over. Pantani attacking in the mountains and beating all comers was a very simple narrative that everyone could get behind,” he says.

As the recriminations of the Festina Affair and Madonna di Campiglio continued to beset bike racing in Italy and beyond, other sports came to the fore. This didn’t only happen in Italy but was also very evident in two of the other major cycling nations, France and Spain. In each of them, football had always been pre-eminent, but cycling was among those on the next tier down, battling with Formula 1 in the consciousness of fans. This changed, though, as new sporting icons appeared, in tennis, basketball, handball and, notably in Italy, Moto GP.

“Even though they had loads of other very good riders, there was no one who was capable of winning the Tour de France, or who had the allure or charisma of Pantani,” says Friebe. “At the same time, in Moto GP there was a crop of very charismatic and successful racers, including Valentino Rossi, Marco Melandri, Loris Capirossi and Max Biaggi. Rossi in particular was well placed to take on the Pied Piper role that Pantani had made his own, emerging as Pantani’s star fell.”

With their wild hair, good looks, flamboyance and no-holds-barred attitude, they seemed more like the music and TV stars that the younger generation were interested in and, as a result, they attracted a lot of new fans to their sport, drawing sponsors aiming to hit the hot buttons in order to reach the right demographic to which to promote and sell their products.

Money talks Former pro Danilo Di Luca, a Giro winner tainted like Pantani by doping and who now heads his own bike manufacturing business, believes this factor is crucial. “The country’s economic crisis has led to the lack of potential sponsors for the WorldTour,” he said in a recent interview.

He also pointed to missed opportunities on the part of those running the sport in Italy. “Cycling was poorly managed in my years and today it is paying the price. We were a worldwide reference, but we didn’t evolve and we fell behind.” Other ex-pros, including iconic sprinter Mario Cipollini, have voiced similar criticisms and concerns, arguing that Italian cycling has failed to adapt the pro cycling’s more worldwide and less parochial framework.

The tendency among the latest generation of Italian fans to look elsewhere for their sporting kicks has also been boosted by the lack of investment in roads and cycling infrastructure. “Even though cycling has always been something that’s part of Italian life, there hasn’t been any real push from the government behind it at a recreational level,” says Friebe. “The upshot of that is that as the traffic in traditional cycling regions such as Lombardy and Tuscany has increased it’s become unsafe to ride, while at the same time the roads in Italy are an absolute disaster. There are lots of roads in Italy, particularly in the south, that you simply can’t ride on.”

Combined, these factors have left Italian cycling wallowing in the doldrums, flickering to prominence occasionally thanks to Nibali’s latest exploit, but generally relegated to the third tier of Italian sports, a gulf between it and football, and a significant gap now to F1 and Moto GP. As a consequence, it’s hard to imagine a young climber emerging now and forcing

their way into the popular sporting consciousness in the manner that Pantani did when he won back-to-back mountain stages in the 1994 Giro and went on to finish second on GC. Perhaps, in a post-Covid-19 world where recreational cycling looks set to become a central part of Italian transport planning, this could happen. But it would also require the emergence of a rider who would not only capture the hearts of the tifosi but also the attention of armchair sport fans, a Pantani for the 21st century.

The last of the old-school champions

One of the foundations of Marco Pantani’s ongoing appeal was the way his style of racing evoked the exploits of cycling’s legendary performers, a comparison that was made even more pertinent by his attitude away from the bike. “There’s a lot to be said for the comparison with the Italian legends of the sport, with the likes of Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali,” says journalist and author William Fotheringham, who interviewed Pantani several times during his career. “Pantani did race in a quite different way and his team was structured around him alone.

He was quite different to most of his rivals in other ways too. He didn’t have a manager until 1999. Up till then, you could just phone him directly and arrange an interview. Usually he’d give you a particular day and time to meet at his mother’s piadineria shop. That was all that it took.”

Pantani’s approach to racing further enhanced comparisons. According to Gianni Mura, La Repubblica’s cycling correspondent since 1967 who died earlier this year, “Like the old riders, he used to race on instinct, he didn’t use the heart rate monitor. When he trained, he drank from fountains and ate bread and pecorino. Even more than the victories, I remember the wait for them, or more precisely for the attack that would inevitably come on a climb.”

When Mura asked Pantani as he rode towards victory in the 1998 Tourde France why he went so fast in the mountains, the Italian replied: “To shorten my agony.” It was the kind of phrasing that not only summed up Pantani’s philosophy, but also fitted with the image that many journalists evoked when writing about him.

“People loved stuff like that,” says Daniel Friebe. “I don’t know how much Pantani cultivated this image or how much it was just journalists who’d come from that more romantic age and were still spinning tales, and were desperate to hold on to those old yarns of Coppi and Bartali.” This tendency, he adds, fed the impression that a lot of talk about cycling is in black and white, that it harks back to the sport’s halcyon days, a trait which is unlikely to appeal to younger fans searching for new narratives to stimulate their passion for sport.

Peter Cossins has been writing about professional cycling since 1993, with his reporting appearing in numerous publications and websites including Cycling Weekly, Cycle Sport and Procycling - which he edited from 2006 to 2009. Peter is the author of several books on cycling - The Monuments, his history of cycling's five greatest one-day Classic races, was published in 2014, followed in 2015 by Alpe d’Huez, an appraisal of cycling’s greatest climb. Yellow Jersey - his celebration of the iconic Tour de France winner's jersey won the 2020 Telegraph Sports Book Awards Cycling Book of the Year Award.