Fausto Coppi: A cycling icon like no other

The Italian shaped cycling like no other rider in history

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Often cited as the rider closest to challenging Eddy Merckx for the honorific title of the best rider in road racing’s history, Fausto Coppi undoubtedly had more influence on the sport than not only the Belgian but any other racer.

>>> Giro d'Italia: Latest news from the Italian Grand Tour

Transformative in his approach to every aspect of cycling, including diet, training, drug taking, equipment, tactics and team organisation, Coppi established a method that his peers and rivals were quick to follow and that remained in place for decades after his premature death in 1960.

Article continues below“There is someone avant-garde in every field, and Coppi was the avant-garde of cycling,” his team-mate Raphaël Geminiani told journalist William Fotheringham in Fallen Angel, the author’s biography of the Italian.

“First he got to know himself, how far he could go physically, then everything else followed that. Every cyclist since has been inspired by him. Nothing fundamental has been invented since Coppi.”

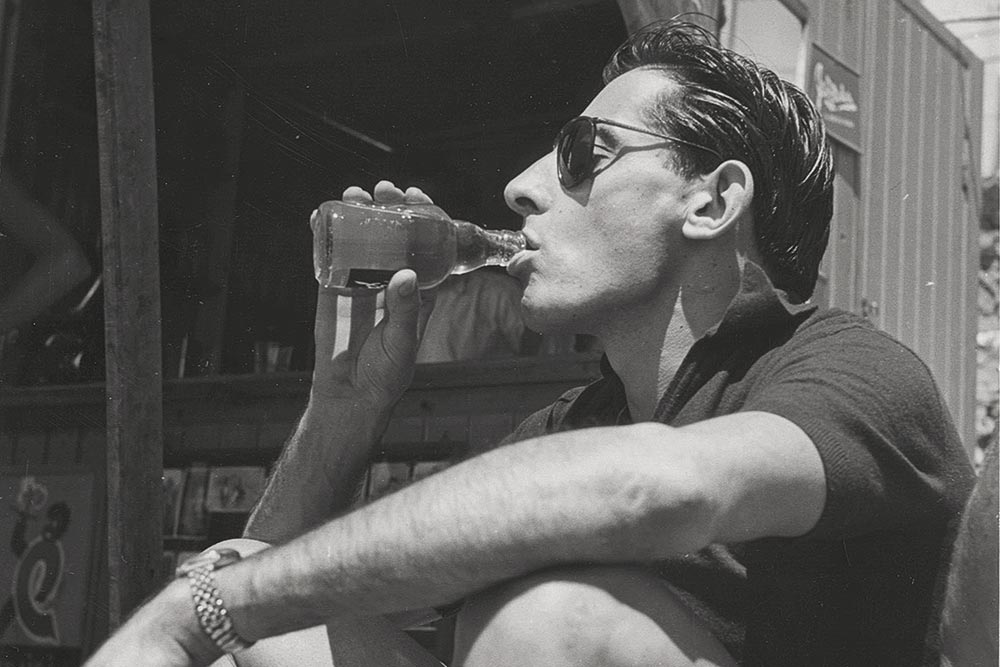

The Frenchman added: “Coppi invented cycling. The war caused cycling to revert to a primitive state: the roads were bad, the bikes were heavy, equipment was poor and not properly maintained, back-up was lousy, nutrition old-fashioned. Coppi was the first to modernise cycling, with the help of the Italian manufacturers. Bianchi bikes were beautiful, marvellous things, but there were also the jerseys, socks, gloves, sunglasses…”

As a teenager, Coppi was certainly talented but hardly exceptional. Stick-thin, pallid and hunched, he rode with his toes pointing to the ground and without paying particular attention to the road in front of him, which meant he punctured frequently. His transformation into a ground-breaking champion began when, in 1938, he was taken under the wing of Biagio Cavanna, whose influence on the rider was immense.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Legend has it Coppi’s blind coach could assess a rider’s potential, form and diet simply through the act of delivering a massage, making adjustments based on his perceptions of their physique, including in Coppi’s case the way in which he slept, so that his position in bed mimicked the one on his bike with one knee pulled up.

Coppi’s breakthrough on the road came when he won the 1940 Giro at the age of 20. Two years later, he set a new mark for the Hour Record in Milan.

But it was only following his release from captivity in an Allied prisoner of war camp in late 1945 that his career took off with a further four Giro successes, two at the Tour de France, nine victories in the one-day Monuments and, in 1953, the world road title.

By that point, the Italian stood head and shoulders above his rivals, having redefined the approach to racing in just about every way possible.

“Coppi definitely modernised the sport massively,” says Fotheringham. “There was a huge contrast between him and his great rival, Gino Bartali, who was so steeped in the pre-war philosophy, the stuff from the sport’s dark ages. Whereas Fausto was very modern, including when it came to doping. He basically took the sport into what was then the modern world. I would, though, question how much of it was Fausto per se and how much of it was Biagio Cavanna, because he was pretty influential as well.

“The thing about Coppi was that because of him the approach to racing changed and that whole philosophy percolated out from Italy. All of the French riders started imitating the Italians. Guys like Raphaël Geminiani and Louison Bobet went and raced in Italy and learned the Italian method, and it all spread from there.

"That influence persisted into the 1960s. You could also argue that without Fausto Italian cycling wouldn’t have been so influential up to the mid-to-late 70s. Arguably Fausto shaped all that and without him it would probably never have happened.”

From 1946 onwards, Coppi and the Bianchi team that Cavanna built around him perfected the way a squad raced. They were the Team Sky of that era, marrying their sponsor’s financial power and technological expertise to the single-minded loyalty of Coppi’s gregari.

Their blueprint was copied by Bobet, Jacques Anquetil, Merckx, Bernard Hinault and every other significant hitter through to Chris Froome and Geraint Thomas in contemporary times.

Rather than resorting to brute strength to ride his opponents off his wheel, Coppi adopted a more strategic approach to stage races, picking out two or three stages where he would attempt to open up a gap and having his domestiques control the action for the rest of the race. He would often look at the key points many times before a race, so that he was completely sure of picking the right moment to attack.

In much the same way, he changed his diet, including during races, eating little and often and substituting carbohydrate for meat. Under Cavanna’s guidance, he also introduced interval training.

Fotheringham believes that it’s debatable whether Coppi is the single most important or influential person in racing, suggesting that Tour founder Henri Desgrange had more of an impact, but points out that Coppi’s place as a cultural icon definitely plays in his favour.

“No other cyclist really rivals him in that way. If you consider that and his place in the Italian national psyche, you could argue that he is the most important figure ever because there is no one else who really combines all those aspects. Consequently, if you look at the question and take it beyond cycling, beyond what takes place on the road, there is an argument for Coppi being the most important figure within the whole history of the sport, and it is a very interesting one,” he says.

“But it depends on your criteria. It requires a combination of this influence on the sport in the long term and the cultural influence on the nation, and then you could say that he’s right at the very top, above even Desgrange.”

Fausto Coppi's Grand Tour double

This article was originally published in Cycle Sport magazine

Fausto Coppi’s legend was created as much by the florid language of the newspaper journalists and the radio broadcasters of the day as the legs and lungs of the man himself.

That is not to say that Coppi was not an awesome man, of course he was, the first modern champion and first to win the Giro and the Tour in the same year.

But almost all his fans learned of his feats by listening to the commentary on the radio and reading the accounts in the sports papers.

And Italians, being Italians, embroidered and gilded their stories, making Coppi a hero at home. Not that there wasn’t an abundance of material with which to create such dramatic pictures.

When Coppi decided it was time to ride, he rode as if that mountain stage was to be his last. He rode at a relentless pace and put minutes into his opponents, often winning a tour with one devastating attack spanning four or five mountains.

Imagine what the factory workers and housewives listening on the radio must have made of that; to hear in every update throughout an eight-hour stage that Coppi was still clear, and stretching his lead.

In post-war Italy, there were in fact two heroes, Coppi and Gino Bartali, but Coppi was the man with all the glamour. When he won the Giro, the ever-demanding tifosi told Coppi he must win the Tour. And when he won them back to back during the same summer, he had become the stuff of legend.

They said it would never be done again, that victory in both epic stage races in the same year was impossible. But Coppi repeated the feat in 1952.

In 1949, Coppi beat Bartali twice, each time with devastating attacks. During the Tour the pair were on the same Italian team, although in truth there were divisions within it. Each rider had those he trusted and those he didn’t, but in the end it fell to Alfredo Binda, the team manager, to make the call, allowing Coppi to ride on when Bartali crashed in the Alps.

By 1952 Coppi had virtually no rivals who could touch him when he was in his best form. He won the Tour by a staggering 28 minutes and was totally untouchable not only in the mountains but also in the long time trials.

Four key stages of Coppi's Grand Tours

1. 1949 Giro d’Italia Stage 17, Cuneo-Pinerolo

Coppi attacks on the Maddalena, the first of five huge mountain passes, to wipe out his deficit overall, claim the pink jersey and put more than 11 minutes into Gino Bartali. It is a trademark of Coppi’s riding style, to pedal away from the rest and keep on going, never letting up, never pausing for thought.

2. 1949 Tour de France Stage 16, Cannes-Briançon

Coppi and Bartali are team-mates —or at least they are in the same Italian team, managed by Alfredo Binda. But both want to win and know they have to ride against one another to do so. On this mammoth 275-kilometre stage from the south coast to the highest large town in the Alps, Coppi breaks away only for Bartali to go with him. Coppi gets a puncture, Bartali waits. Later on, Bartali punctures and Coppi waits. They ride together to the finish, attempting to drop each other but unable to do so. Bartali wins the stage in a time of 10 hours 25 minutes.

3. 1949 Tour de France Stage 17, Briançon-Aosta

The very next day in the same Tour, the stage finishes in Italy and will crown the overall Tour champion. Bartali leads by 1-22 overall and the pair attack once again. And once again Bartali gets a puncture and Coppi waits for him. But then Bartali crashes, injuring his foot.

Binda cuts Coppi free, allowing him to ride for himself. By the finish he is 4-53 up on Bartali who, though hurt, is still able to finish second on the stage.

4. 1952 Tour de France stage 10, Lausanne-Alpe d’Huez

Although Coppi’s performance on stage 11 to Sestriere was more impressive, this stage is a landmark in Tour history. It was the first stage to finish at the summit of a mountain. Coppi wins on Alpe d’Huez by 1-20 to take the yellow jersey by a five-second margin. Next day he slaughters the field, crossing the Croix de Fer, Galibier and Montgenèvre in first place to win at Sestriere by seven minutes and put the Tour beyond doubt.

Michael Hutchinson is a writer, journalist and former professional cyclist. As a rider he won multiple national titles in both Britain and Ireland and competed at the World Championships and the Commonwealth Games. He was a three-time Brompton folding-bike World Champion, and once hit 73 mph riding down a hill in Wales. His Dr Hutch columns appears in every issue of Cycling Weekly magazine