Pavé power: what it takes to win the Tour of Flanders

Not for nothing are the cobblestoned spring Classics feared and revered by the pros who race them. They know how hard these races are, and with the recent use of power meters, they have some astonishing figures to prove it

A couple of years ago Cycle Sport witnessed an unusual interval training session. Magnus Backstedt was on his annual pre-Paris-Roubaix pilgrimage to the Hell of the North. Three years before, he had won Roubaix, and, despite a bad crash during the preceding winter, he wanted to win it again.

We were in the forest of Arenberg. Backstedt wanted to test his newly healed shoulder and see exactly where his fitness was, with the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix looming on the horizon.

Equipped with an SRM power meter, the Swede rode up and down Arenberg five times, increasing his effort with each passage along the notorious stones. The efforts were all done in the direction of the race route. This session was designed to renew his acquaintance with the most iconic section of the race, and to test his form. Backstedt recovered from each pass by riding slowly along the cinder path back to the wallers-Arenberg mine, where he did a u-turn and blasted back down again.

The last run was the test. Backstedt knew the power output he'd need on this stretch on race day. He had to see that figure today, and see it with no problems from his iffy shoulder, otherwise he could forget about adding another cobblestone trophy to his collection.

Backstedt launched himself into the forest and thundered through Arenberg. His bike rattled the tyres skipped and slid, but he was driven inexorably along the rocky road. After it was over, and Backstedt had caught his breath, he was smiling broadly.

“Yeah, that’s fixed,” he said, referring to his shoulder. “And the numbers are there,” he added.

Revelation

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The numbers were a revelation. “I need the same power output as I can do in a pursuit race on the track,” he told us. “I have ridden 4-30 for 4,000 metres, and that needs upwards of 550 watts from me. I’ve used SRMs in Paris-Roubaix, and the figures are the same for each cobbled section if you want to stay at the front.”

That is staggering. Multi-champion pursuiter, Bradley Wiggins confirmed these figures: “I put out 580 to 600 watts when I ride under 4-20.”

But Wiggins has to do that a maximum of twice in one day in a pursuit competition. A Paris-Roubaix winner has 28 sections of cobbles to negotiate, all ridden at close to pursuit power.

“I’ve timed them. The cobbled sections take between two and six minutes each to ride at race pace, and once you are on the pavé, the longest gap of smooth road between the cobbles is 20 minutes. But that goes down to less than two minutes in some places,” says Backstedt.

On top of that, the race duration is upwards of six hours and bad weather is another factor. Similar power outputs are required to ride the Tour of Flanders, where the short climbs can be viewed as tilted versions of the Roubaix pavé.

Cobbled Classics have always required a special kind of rider, but SRM and other power-measuring devices have quantified just how demanding they are. We asked one of the world’s leading cycling coaches and an expert in the use of power meters, Hunter Allen, to analyse the demands of a cobbled Classic and to outline how he goes about training riders for them.

Allen’s way

“The two key components of the cobbled Classics are their length, which requires a tremendous amount of muscular endurance, and the sustained bouts of very high power output on the cobbled sections and short hills.

“They are different from normal races where a rider may be in the peloton for a long time, then have to make one or more 20 to 30-minute sustained efforts. In a cobbled Classic, a rider has to endure much smaller periods of huge power output,” says Allen.

Commenting on Backstedt’s pursuit analogy Allen said: “I’m not surprised he sees pursuit numbers. I’ve seen clients’ SRM files where they are riding at 120 to 200 per cent of their functional power threshold — the highest power output they can keep up for an hour — for two to four minutes in the Classics.”

His first step in preparing a cobbled Classics rider is to devise a kind of training he rarely recommends to any other cyclist.

“It’s the only time I believe in this, but a Classics rider has got to do some six and seven-hour rides. Virtually no one else needs these rides, but the Classics are still six and seven-hour races, and your body has to cope with that.

“Then we’d need to address the power outputs required. These are very much in the VO2 max territory, so a number of VO2 max intervals would need to be done. These would begin at three minutes and build to five, and are designed to train the sustained power output needed.

“At the same time, though, we would need to work on anaerobic capacity. This is the ability to go very hard — harder than VO2 max pace — for 30 seconds to two minutes. Finally, we would need to train the ability to recover quickly,” says Allen.

That is Allen’s training prescription for the cobbled Classics, but he stresses that there has to be an order in which the training is done.

“Peak values come first. You’ve got to make sure the rider is in the region of 700 watts for one minute, otherwise he won’t be a contender.

“After that comes repeatability. Once I’ve seen 700 watts for a minute, I’d look at working on doing 15 times one minute at 650 watts, with a one minute rest, as a key session, maybe even cutting the rest as training progresses. Shortly after beginning one-minute power work, we would start the long rides and VO2 max sessions, but one-minute power output is still very important.”

Power rules

As Allen points out, high power output is the key that unlocks the cobbled Classics. The long rides certainly help, as do VO2 max intervals, and many riders also do 20-minute efforts to increase their functional threshold power. But the key sessions are exactly what a top track pursuiter would do, and Backstedt takes that comparison further.

Bradley Wiggins points out that his key session when he is preparing for a pursuit is 30-second intervals.

“Obviously, I do a lot of other things,” he says. “But coming into a pursuit, I’ve got a wattage I want to see in 30 seconds, and that is 650 to 700 watts. From that figure I can tell pretty much what my time will be for 4,000 metres.”

These 30-second intervals are the cornerstone of Backstedt’s pursuit preparation as well, but he also used them in the run-up to Paris-Roubaix.

“I would do long rides — six and more hours — but within those rides I was always doing something else, like three to four 20-minute efforts at functional threshold or shorter VO2 max intervals.

“I also varied the length of my recovery intervals. For example, some days I did one 20-minute threshold effort per hour; on others I did three by 20 minutes, but with only three minutes between each. But, one of the most important sessions in my build-up was doing 30-second intervals on my turbo trainer, and for them I was just north of 1,000 watts,” says Backstedt.

That is a truly amazing figure, and something Backstedt’s coach goes into in more depth (see separate story). It’s the big weapon in Backstedt’s armoury. “The biggest sustained power output I’ve ever managed is 1,100 watts for just over a minute when I’ve been leading out a sprint,” he reveals.

Resilience

They are huge numbers, but in the cobbled Classics they have to be underpinned by enormous endurance and resilience.

“You are trying to dictate, but others are dictating to you as well; you have to be able to answer everything. And don’t forget, the race goes on between the cobbled sections too. So, the way I used my 30-second intervals, which does differ from how a pursuiter would prepare, is that I kept doing them until the power fell off. Then, each time I came back to that session, I’d want to see more 1,000-watt intervals,” says Backstedt.

“If you’ve got the watts up high enough then recovery is the key to races like Roubaix and Flanders. A successful rider in Flanders will have made 40 efforts from 15 to 20 seconds long, and climbed 10 to 20 hills in the one to two-minute range, all at between 450 and 760 watts. And he has to be able to recover within 30 seconds and go again, and again, and again,” says Hunter Allen.

Like all top-level sport, the demands of the cobbled Classics are a big ask. They require a rider who is naturally capable of putting out massive amounts of power, and doing it again and again, over a very long day. There are very few riders in the world who have the right physical equipment to fulfil these requirements, which is why every year these iconic races are contested by just a handful of favourites, but it is also why nobody ever flukes a cobbled Classic.

SRM file analysis

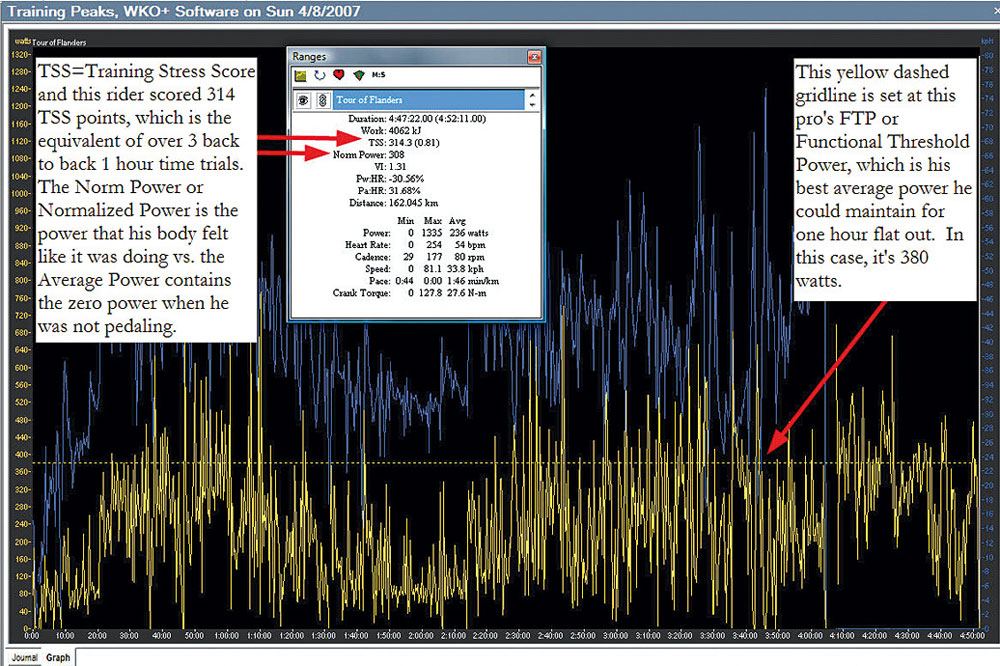

Hunter Allen examines an SRM file from Roger Hammond that tracks his exertions at the 2008 Tour of Flanders “Unfortunately Roger punctured four hours into the race, chased for a while, then abandoned. Still, he raced for nearly five hours, did 4,000 kilojoules of work, had a normalised power of 308 watts for the entire race and a training stress score of 314 points.

“Normalised power was created by Dr Andrew R Coggan and is used in the TrainingPeaks WKO+ software to help riders understand the metabolic cost of cycling better. Average power doesn’t take into account coasting, but normalised power does, and it takes into account the way the body deals with waste products to give the true metabolic cost of effort. Training stress score measures the stress accumulated during a ride. A score of 100 equals one hour at their maximum aerobic pace, so this rider did the equivalent of three one-hour time trials back to back.

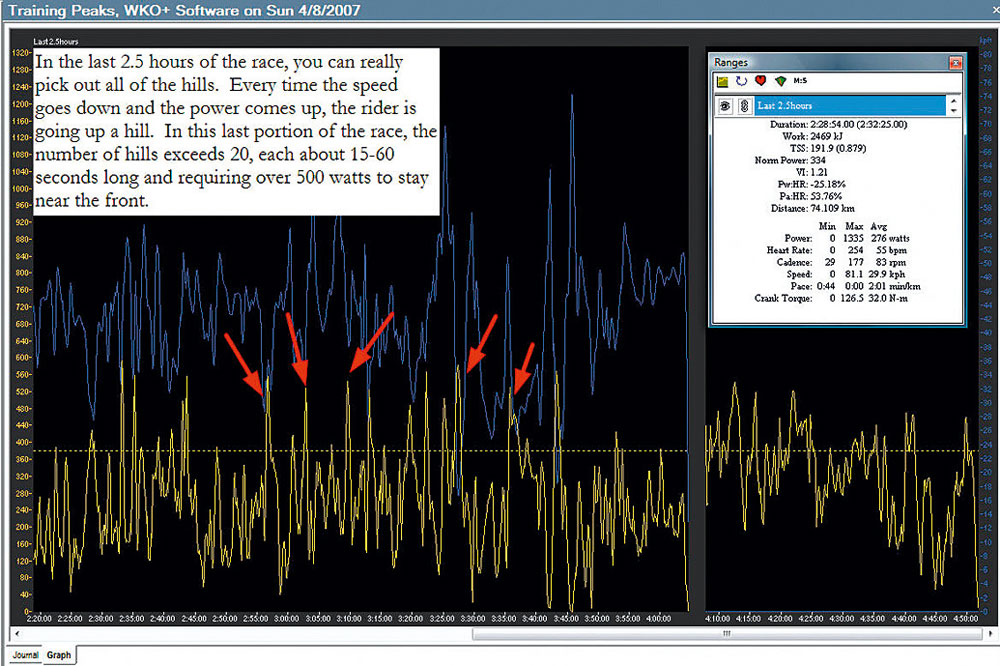

“As we take a closer look at the end of the race, we see just how short the big power efforts are. The power spikes coincide with the famous hills of Flanders, the Oude Kwaeremont, Koppenberg, Paterberg and the rest.”

Backstedt’s way

Coach Steve Benton explains why, even among cobbled Classics specialists, Magnus Backstedt was a very special case.

Steve Benton doesn’t have the history of training pro riders that Hunter Allen has, but that was one reason why Magnus Backstedt hired him.

“Magnus has a different body type to almost any other pro rider in the world,” says Benton. “The guys that contend in the spring Classics are often referred to as big guys, but none of them would stand out in the pub. Magnus would. Even the Tom Boonens and Thor Hushovds of this world are only 80 kilogrammes at the most. When he’s in mid-season and trimmed right down to the bone, Magnus is 10 to 12 kilogrammes heavier than that.”

Benton is a keen cyclist. “It’s ironic really. Cycling is my sport — the sport I do when I can — but I tended to steer clear of coaching it for that reason,” he says.

But Benton’s coaching experience is still vast. He’s worked for 10 years in elite motor sport as a strength and conditioning coach for F1 drivers, but has done most of his work in world rally, where he has coached a number of top drivers including Richard Burns and Timo Makinen.

“I started using SRMs when they first came out and so I got a good understanding of how they relate to physiology. But I think Magnus came to me because I looked outside of the box.

“The best way to explain what I’m talking about is to take the analogy of a four-kilometre pursuit a little bit further. Magnus quite rightly pointed out that pursuit power outputs are similar to those needed to contend in a cobbled Classic. But let’s look at a 4-30, 4,000-metre pursuit as an example. You can achieve that time in different ways. The energy components that make up that time can vary considerably.

“One rider could do that time using mostly his aerobic system, whereas another might have used his anaerobic system more. So, when you’ve found out these proportions, you can concentrate on either system.

“Magnus has a huge anaerobic system. He’s quite explosive, so in his training we did a lot of 30-second efforts where he puts out 1,000 watts. We did them because it’s best to develop what a rider has already got, but also for a tactical reason. While putting in a big effort on the cobbles, Magnus could use his anaerobic system to make big digs — digs that were explosive and hurt the others.

“But, being a big guy, Magnus is also very vulnerable. He sits high up, and riders love to shelter behind him when he’s powering along, so he’s vulnerable to counter-attacks. We trained his anaerobic system so, as well as making the big digs to hurt others, Magnus would be able to use his anaerobic power when the others attacked him.”

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast