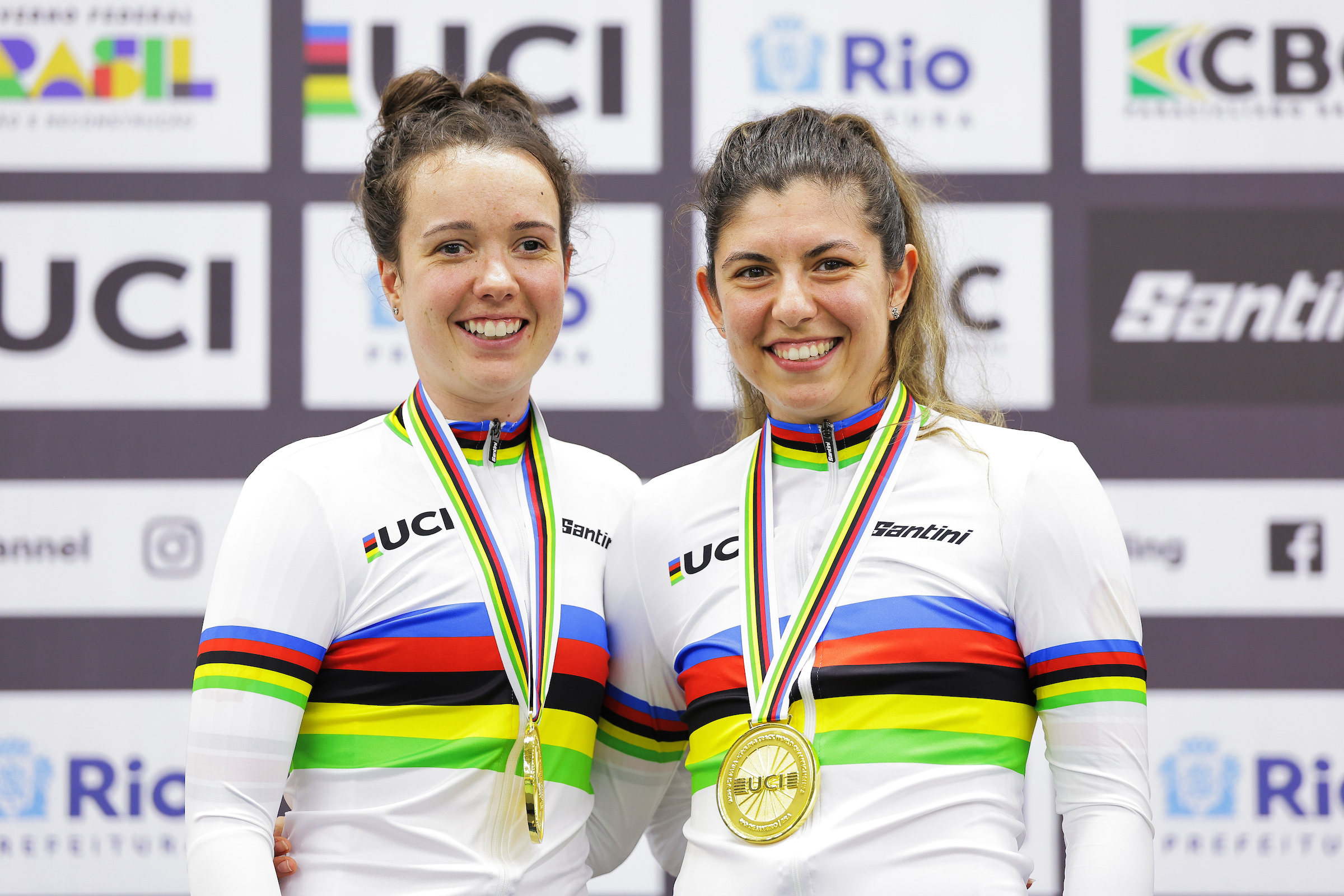

'Back then I was on the edge of life – but now I'm a multi world champion': Para-cyclist Lizzi Jordan's golden comeback from near-fatal food poisoning

Keen equestrian Lizzi Jordan was riding high until a freak illness changed her life forever. Now, having swapped reins for handlebars, she is not only back in the saddle but winning on the world stage

Lizzi Jordan and her pilot Danni Khan have just won a hat-trick of gold medals at the UCI Para-cycling Track World Championships in Brazil. Cycling Weekly spoke to Jordan in November for our 'My Fitness Challenge' series – first published in the print magazine and reproduced here

Riding has always been a passion for Lizzi Jordan, but it was horses rather than bikes through her younger years. “I spent all my weekends at the stables with my friends,” the 26-year-old tells me over Zoom, speaking from her home in Guildford, Surrey. “It was a great social way of meeting new people and a great hobby.” Jordan was living life to the full as a bright, horse-crazy youngster, doing well at school during the week and galloping around the countryside at weekends. “Often on the craziest of horses,” she adds, “and often getting thrown off – but I loved it, and you’re pretty robust when you’re young.”

After getting a good set of grades at GCSE and then A-Level, she began a psychology degree at Royal Holloway University in London. It was shortly after completing her first year, one evening in September 2017, that she sat down for a meal that would change her life forever. When I ask her what happened, she begins by explaining that her account is, by necessity, pieced together from what doctors and her family have told her. “The body has a strange way of protecting you – a large part of 2017 I’ve lost from my memory completely.”

This much she knows: after eating a takeaway meal with her family, she and her older sister Chloe began to feel ill. “From what I understand, it started with a very bad upset stomach, extreme stomach cramps. We went to the GP, who said it would pass, just like a tummy bug.” While this was true for Chloe, who soon began to recover, Lizzi’s condition deteriorated rapidly. “My mum took me to A&E, but I was going very quickly downhill, by now delusional, talking nonsense, not knowing where I was.” Realising Jordan’s life was in danger, doctors rushed her into intensive care where she was put into an induced coma.

Her condition continued to decline and she was put on life support. “I had multiple organ failure, and was very much on the edge of life,” Jordan says. “It was extremely touch-and-go.” The E. coli infection had triggered a seismic overreaction from Jordan’s immune system, which was waging war on all her internal organs. “It went on a rampage around my body,” she continues, “my kidneys, my heart, my lungs, my eyes, my brain – nothing escaped.” As a last resort, doctors administered a pioneering new antibody treatment called Eculizumab. Mercifully it worked, and finally, after three months in a coma, Jordan opened her eyes.

Still under heavy sedation and understandably bewildered, it took several days to take in what had happened to her – and to ascertain which, if any, parts of her body had sustained lasting damage. “I was still so poorly and lethargic that it was the least of my concerns, but it dawned on me as I got a bit better in hospital and they wanted me to start moving around,” Jordan pauses. “That’s when things started to become difficult.” Muscle wastage from three months bed-bound had sapped her strength – but there was a bigger problem too. “I soon learned that when your body is in a critical state, it can neglect your senses, as it prioritises your vital organs,” she explains. “This meant toxic blood had sat behind my eyes and starved my retina and optic nerve of oxygen, leading to optic nerve atrophy. The system that connects my eyes to my brain no longer works; no signals can pass through. My sight is totally gone.”

It is hard to imagine having to come to terms with so much all at once, but Jordan is unflinching in her account. She calmly explains that while in hospital her sight loss did not greatly affect her, since she could not yet move around or care for herself independently. Meanwhile her friends and family did everything they could to support her emotionally, and even arranged a bedside visit from a horse. “In the horse walks,” Jordan recounts the scene like the set-up to a joke, “and they got it into a lift, up to the 13th floor of the hospital, but someone intercepted the lift on the way up – the door opens at floor five and a patient gowned-up for surgery is greeted by a horse’s bottom!”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The extraordinary distractions of the hospital stay ended a month later when, shortly before Christmas 2017, Jordan was allowed to go home. It was now that the full challenge of living without visual perception confronted her. “Stepping out of the taxi, it was absolutely terrifying. There were just really loud noises… a bus passing, a person brushing past too close,” she depicts a disorientating, chaotic din. “It was overwhelming, sensory-wise, completely overwhelming.”

As she strove to reassemble her life and regain autonomy, the upheavals came thick and fast. “That’s the thing with sight loss,” she says, “there are constantly new hurdles to face.” Once she had mastered navigating around her home, it was on to more intricate tasks like preparing food and using screen-reading software to operate phone and computer. The next major step was to start recouping her fitness. “Six months after getting out of hospital, I set myself the target of completing our local Parkrun,” she recalls. “It was nothing flashy, about 45 minutes, but it took so much out of me that I was sick at the end.” The extreme difficulty only made her more determined – and her dad, as guiderunner, had no choice but to follow suit. By the end of the year, she had recorded a 26-minute PB.

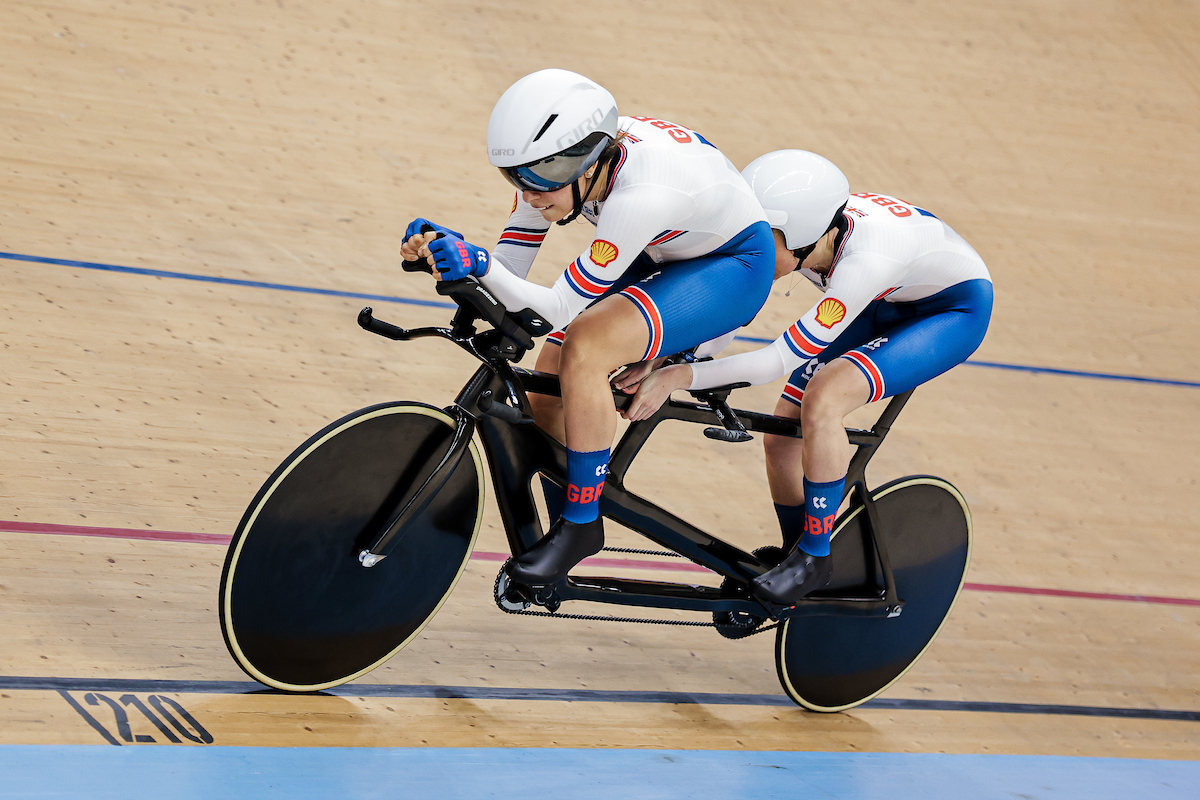

Elizabeth Jordan and pilot Dannielle Khan in action at the Para-cycling Track World Champs in Rio

Guildford’s got talent

Over the next two years, Jordan continued to build her fitness, ran a marathon, returned to horse riding, and in summer 2020 heard about an upcoming talent ID event being run by British Cycling. She had never cycled competitively but the prospect appealed, so she signed up. “I’ll never forget that day in Manchester,” she says. “I turned up with my dad and I was instantly led away from time I’d been assisted by someone not familiar to me. Socially and mentally, that was a big step for me.” Despite being out of her comfort zone, Jordan put her all into the power tests and a few weeks later received a call from BC, inviting her to join the para-cycling Foundation team. “Another moment I’ll always remember is the British Cycling van turning up with a static bike for me to start training on – the journey had begun.”

As with her running, Jordan’s appetite for improvement quickly took hold. “The training constantly got harder, but my numbers got better and better,” she says, breezily. “There were puddles of sweat on the floor. It hit me hard. While I was already quite fit from the marathon, that was nothing compared to the cycling schedule.” I’m struck by the way she has turned each challenge into an opportunity to test herself. “When I first got home from hospital,” Jordan reflects, “my life seemed really bleak – I’d lost my driving licence, the ability to go to university independently; I’d lost my boyfriend; I’d lost a lot of things that were really close to me. I needed something to aim towards to give me a new sense of achievement.”

Now she had that aim: to perform at the highest level of para-cycling, and sure enough, Jordan soon began to attract the attention of the GB selectors. After a promising debut in early 2021, Covid-19 disruption put her racing on hold. Finally, in October last year, the wait was over: Jordan was called up for the Para-cycling Track Worlds in France. “That was where I won my first silver medal,” she glows, “which was incredible – I hadn’t expected it at all, so I was really totally buzzing. I started to think, ‘Oh, I might be getting somewhere here’.” Getting somewhere she certainly was: to big-time success at her home World Champs this August. Paired with tandem pilot Amy Cole, Jordan won gold in the mixed team sprint and bronze in the 1km time trial.

Aside from these results earning her promotion to the Podium squad and putting her in line for Paralympics selection, it must have felt magical to win two medals in front of a home crowd? “It was one of those experiences,” she pauses to let the memory flood back. “Although I can’t see, the noise and the feeling of the stadium vibrating – I didn’t need to see it, I could feel it,” the sensations are almost tangible in her voice. “It’s those moments that make me realise all the hard work has been worth it. I might not be able to see the gold medal or the photos of myself on the podium, but I get to feel it.”

Coach's view: 'She keeps me on my toes'

GB para-cycling coach Helen Scott has been alongside Lizzi since day one

“I first met Lizzi when I was still an athlete myself – at the talent ID weekend she attended. We were looking for a stoker for the tandem that I would be piloting at the Tokyo Olympics. I was lucky enough to guide her through the testing. We saw straight away that Lizzi was an endurance rider, whereas I was looking for a sprinter. Her power data was so impressive that we invited her onto the Foundation programme. Fast-forward two years, and I’m now her coach – we’ve come full circle!

“Lizzi has made great progress, and since I started coaching her 18 months ago, she has won three medals from two world championships. It’s been amazing. What’s most impressive about Lizzi is how she always wants to learn and improve; she really wants to understand what she is doing and why. I love that as a coach – she challenges me nearly every day, keeping me on my toes. “I’ve got to be honest, if we pair her with the correct pilot, then I genuinely believe the sky’s the limit. It’s really exciting.”

A longer audio version of this conversation is available on David Bradford's podcast Ways of Not Seeing.

The full version of this article was published in the 30 November 2023 print edition of Cycling Weekly magazine. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered to your door every week.

David Bradford is senior editor of Cycling Weekly's print edition, and has been writing and editing professionally for 20 years. His work has appeared in national newspapers and magazines including the Independent, the Guardian, the Times, the Irish Times, Vice.com and Runner’s World. Alongside his love of cycling, David is a long-distance runner with a marathon personal best of 2hr 28min. Diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in 2006, he also writes personal essays exploring sight loss, place, nature and social history. His essay 'Undertow' was published in the anthology Going to Ground (Little Toller, 2024). Follow on Bluesky: dbfreelance.co.uk