Aero for everyone? I got an AI-based bike fit and saved dozens of watts

I got a bike fit from AiRO, an AI-driven app that gives bike fitters actionable CFD modeling without the wind tunnel

Aerodynamics in cycling is a tricky business. On the surface, it seems simple: smaller, smoother, strategically shaped objects move through the air more efficiently. But beyond those broad strokes, the science gets deeply complex.

Until recently, meaningful aerodynamic assessments required wind tunnels and/or sophisticated on-bike instruments, both of which are costly and time-consuming. AiRO, a Salt Lake City–based technology firm, aims to change that with an AI-powered aerodynamic analysis app that lets bike fitters optimise any rider’s position using just a few measurements, a stationary trainer, and a few photos.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) programs have long supported wind tunnel and track testing at the WorldTour and Olympic level, but they rely on detailed 3D scans and long processing times to build digital avatars.

AiRO replaces those scans with AI-driven photo analysis, cutting turnaround to minutes. Most importantly, it makes quantitative aerodynamic testing available to a much broader audience.

To understand how it works, I met the team behind AiRO and went through the fitting process myself. Here’s what I learned and how many watts I was able to save.

AiRO background: Specialized and speed skating

Until recently, meaningful aerodynamic assessments required wind tunnels and/or sophisticated on-bike instruments, both of which are costly and time-consuming.

AiRO is the brainchild of Ingmar Jungnickel, an award-winning aerodynamicist with a long history in cycling aerodynamics. His expertise was honed during his years at Specialized, where he served as one of the company’s lead aerodynamicists.

“I had the keys to the wind tunnel and Specialized really encouraged open exploration as well,” Jungnickel, a self-described aero-nerd, said. “I did that quite a lot in the first couple of years. I would stay late after work with a bunch of the other aero friends.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“We'd order pizza and we just test ourselves for another four, five hours. At the other tunnels, where you pay per hour, you just don't try crazy things. You're like, ‘This test is going to cost us $600, do I really want to test this?’”

Specialized, during their “Aero is Everything” era, was all for this unstructured wind-tunnel tinkering. In fact, it all played a part in the innovation around vaunted tech like the Specialized Shiv, Venge and various iterations of the Tarmac. Functionally, this also enabled Jungnickel to complete the full bell curve of aerodynamic understanding.

“First, you get into this phase where you realise how your aero is structured. So the simple models. Then you realised those models don't really work – everybody is different. Then, when you test even more, at some point, you start seeing more of the correlations, but it takes a lot of testing to get to that point.”

After his nearly nine years with Specialized, Jungnickel went on to speedskating in support of the US national speedskating team. And this is where AiRo was born. His AiRO app was first developed for use by the U.S. Speed Skating team in preparation for the 2026 Winter Olympic Games. His results with the speed skating team were so good that he was able to spin off that app to a public technology, bringing AI aero modelling to the public.

But rather than focusing on speedskating, Jungnickel returned to his roots, developing an app for high-end bike fitters and performance coaches, including WorldTour clients, to model and test rider positions for aerodynamic optimisation.

“We chose to work with high-end bike fitters only because you can try whatever you want in the app,” he said. “You can bend the digital twin into any position. And we want you to have the best position, not just the lowest drag position."

Even though a professional bike fit can seem expensive, it’s a mere fraction of the cost of aerodynamic wind tunnel testing. To bring a bike fit expert to a wind tunnel and run two hours of testing typically costs $2,000-$2,500. While the wind tunnel can test equipment that AiRO can’t, AiRO can account for testing everything else—including helmets—for a fee well under $500 in a similar session.

What’s more, all those non-equipment-related factors AiRO tests for account for roughly 60-75% of the total aero equation.

“If you run the dollar spent per improvement, we're seeing 20 to 30 watt average improvements from aero testing, and that is for a few hundred dollars," said Jungnickel.

"Wind tunnel testing is still a great return on investment with a $2,000 session, which is actually money well spent. But now we can offer a similar service for $200.”

A focus on body position, not equipment

I received my AiRO bike fit at a co-working space in Tempe, Arizona. Jungnickel flew in to meet with Brian Stover, an independent aerodynamic expert and bike fitter with over a decade of experience. Stover is one of the first fitters to have access to the AiRO technology. I was one of their guinea pigs.

“First, we will look at reach and stack,” Stover explained as I started pedalling on a trainer. “How you're holding your head, how you're riding the bike, do you tend to have your elbows out, or do you tend to ride with them in? Do you tend to have your hands this way to bring your elbows in? How are your shoulders looking? Are you rounded? Are you like squeezing your shoulders up? Are you relaxed?

“That's where you need to start to build out the rest of the fine-tuning.”

Stover says the AiRO app has made his aero-specific fits a lot more effective for one key reason: it offers a massive head start to the complicated process of personal aero optimisation.

“This is a way to pre-screen some of those basic tests that you might do to narrow down the options in the wind tunnel, because if you're charging people $12-15 a minute, you don't want to get in there and test everything under the sun. You need to have a pretty definitive list of what you want to test and how you want to test it.

“Using this app is a way to reduce some of those variables beforehand, so maybe you're limited to three or four positional changes that you already know have a higher probability of working.”

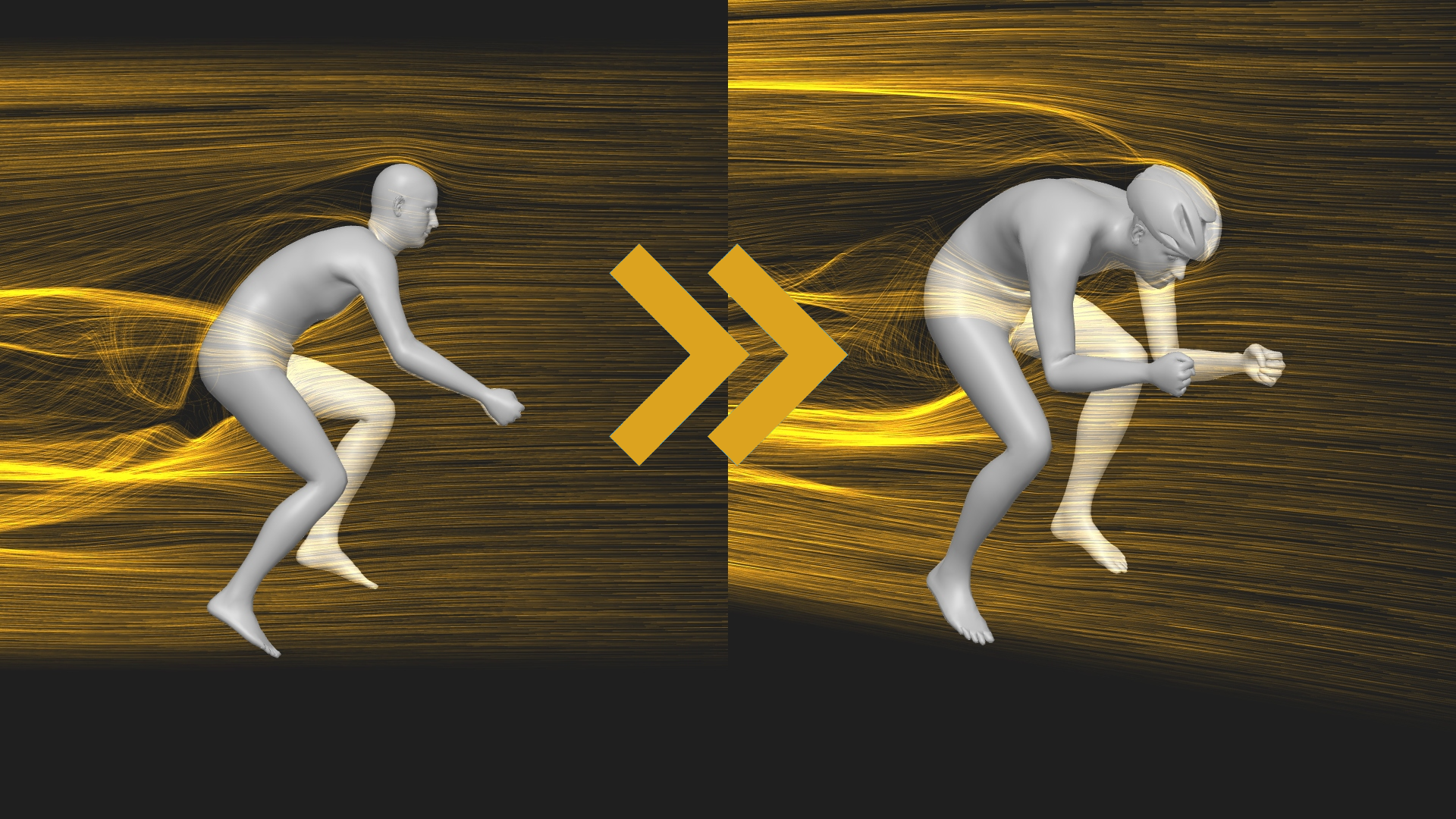

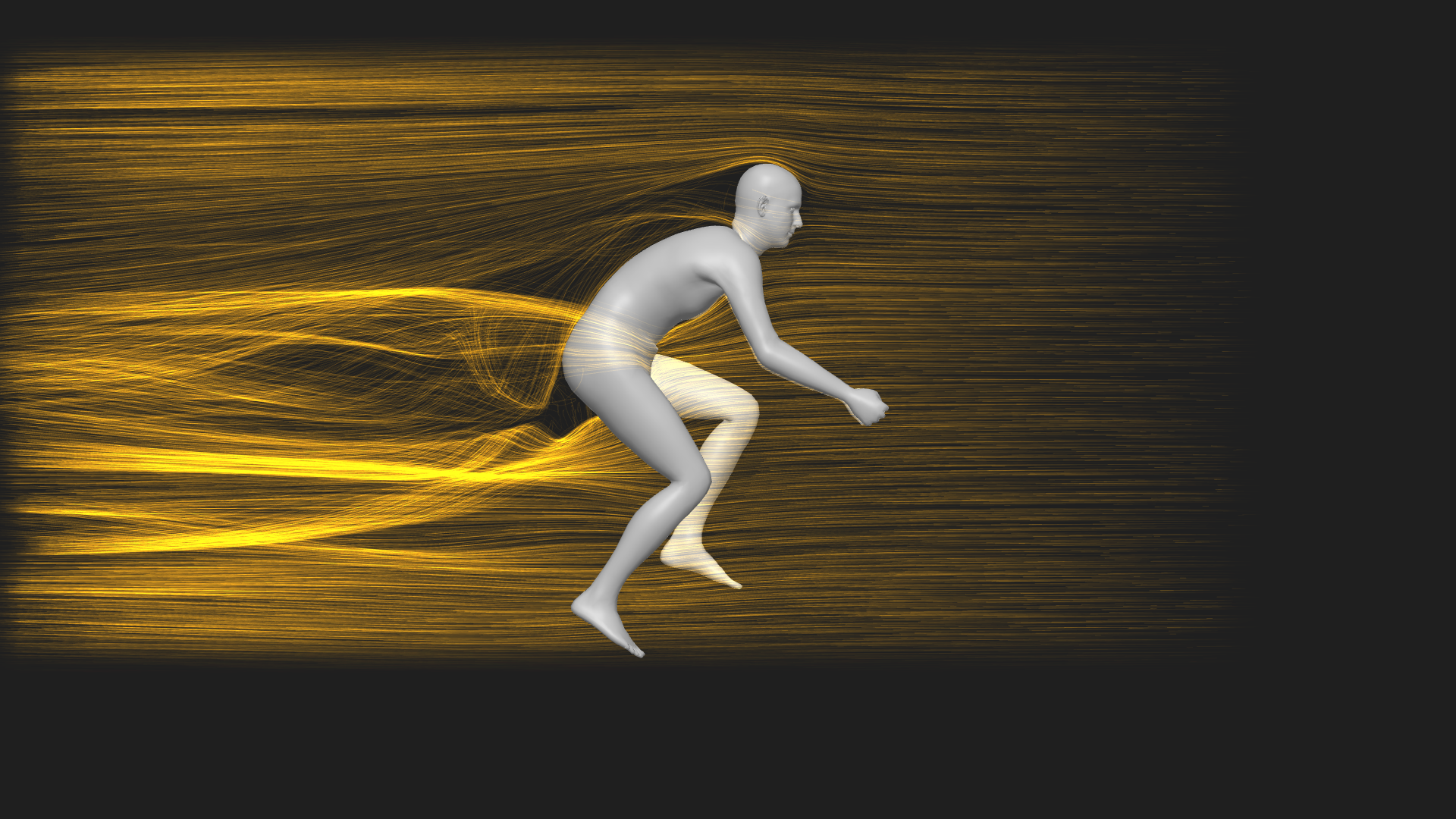

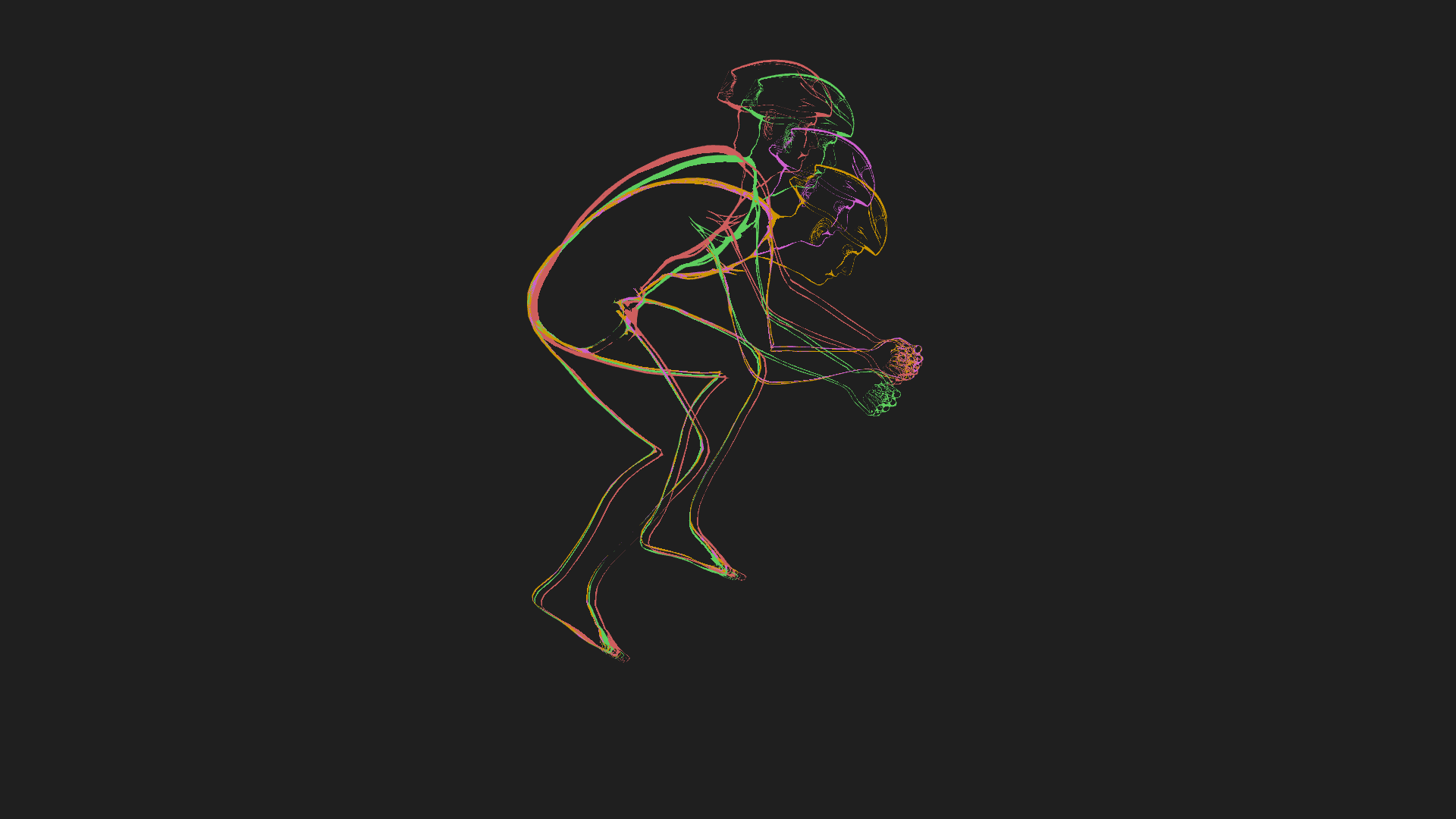

To achieve all this, it starts with a photo to get a parametric human model. That, along with a few body measurements such as weight and height, is entered into the app. Then, it's a short wait to get the “virtual twin,” which is the basis for the rest of the modelling to come.

As we mentioned earlier in the article, there are other CFD models that WorldTour teams and Olympic programs use; they just require full 3D body scans and extensive manual corrections to be effective. The picture-based AI software allows AiRO to use 4,000 different adjustment points to get a precise representation of the rider’s body contours and produce more robust data with much less manual input.

After that, it's up to the rider to show their baseline position on the bike, take photos from the side and from the front, and recreate that with the digital twin in the app. That position is the first simulation that runs on the most powerful supercomputer AiRO can rent. 15 minutes later, the simulation is done, and the adjustments can begin.

“That is where the app begins to do its work and the magic starts happening,” Jungnickel said when the time came to start playing around with models and simulations. “We can do iterations purely on the digital twin, and that takes 30 seconds for each variation to build, and it takes seven minutes to run.”

The AiRO testing and fitting

At this point, all the setup was wrapped up, and it was Stover’s time to shine.

Unfortunately, my personal road bike, a Haro Rivette, has an integrated cockpit, so the changes we could make were always going to be limited. Most of the changes would come from the seat and from the few spacers we had to work with at the front end of the bike.

“First of all, you're looking to optimise aerodynamics by reducing drag, right?” Stover said when getting me started. “So if I can shave 10-12 watts of drag off without causing you any decrease in power, then suddenly you're now roughly 1 second per kilometre faster and nothing else has changed.

“Then, I put you into a position where you're comfortable, aero, and you can still put out the power, so we reduce drag and we can increase power a little bit, and/or increase comfort. Then you can put out five watts more, but you also reduce drag by 10 watts, so you’re gaining from both ends.”

Generally, I am not picky when it comes to bike fits; it is a by-product of hopping on different setups for work and constantly switching between road, gravel and mountain bikes. I thought my position was fairly neutral. My stem isn’t slammed, but it only ever has 1 or 2 5mm spacers underneath, and I typically hover around 120mm stem length.

What was immediately apparent was that this wasn’t the right setup to optimise around aerodynamics. And finally, there was concrete data to back it up.

What really underscored the fault of this approach was positioning my digital twin in a position that was equivalent to riding in the drops. Ideally, this position would have a lower CDA (the aerodynamic term for the drag of an object) than the standard baseline position of riding in the hoods. In reality, it was worse.

Ideally, at this point in the fit, he would have swapped stems, and we’d be off. But with a one-piece integrated cockpit that wasn’t an option, it was noted for a future change. There were still things we could do to find aero gains within the constraints of the bike’s position. And that was where I found the AiRO app to be the most impactful.

Finding dozens of watts of aero gains

Using the virtual twin as my guide, we began tinkering with different elements of my body position within the set constraints of the front of the bike. Using Stover and Jungnickel’s insight as a guide, we looked at my forearm bend, head position, and how my shoulders contoured as the main points of change. We then took these changes from my virtual twin to my position on the trainer, using it as a guide for me to try different things and report back what seemed beneficial.

Throughout this process, I pushed my saddle forward and tilted the nose down, giving me greater ability to pivot my hips and adjust my hands and shoulders. That, in turn, let me move my forearms down to a parallel position with the ground, and really drop my head between my shoulders. Matching the virtual twin to that position then gave us the data we were really hoping for: when the going gets really important, just how many watts can I save at race pace?

Using the AiRO app to dial in the next position we are testing

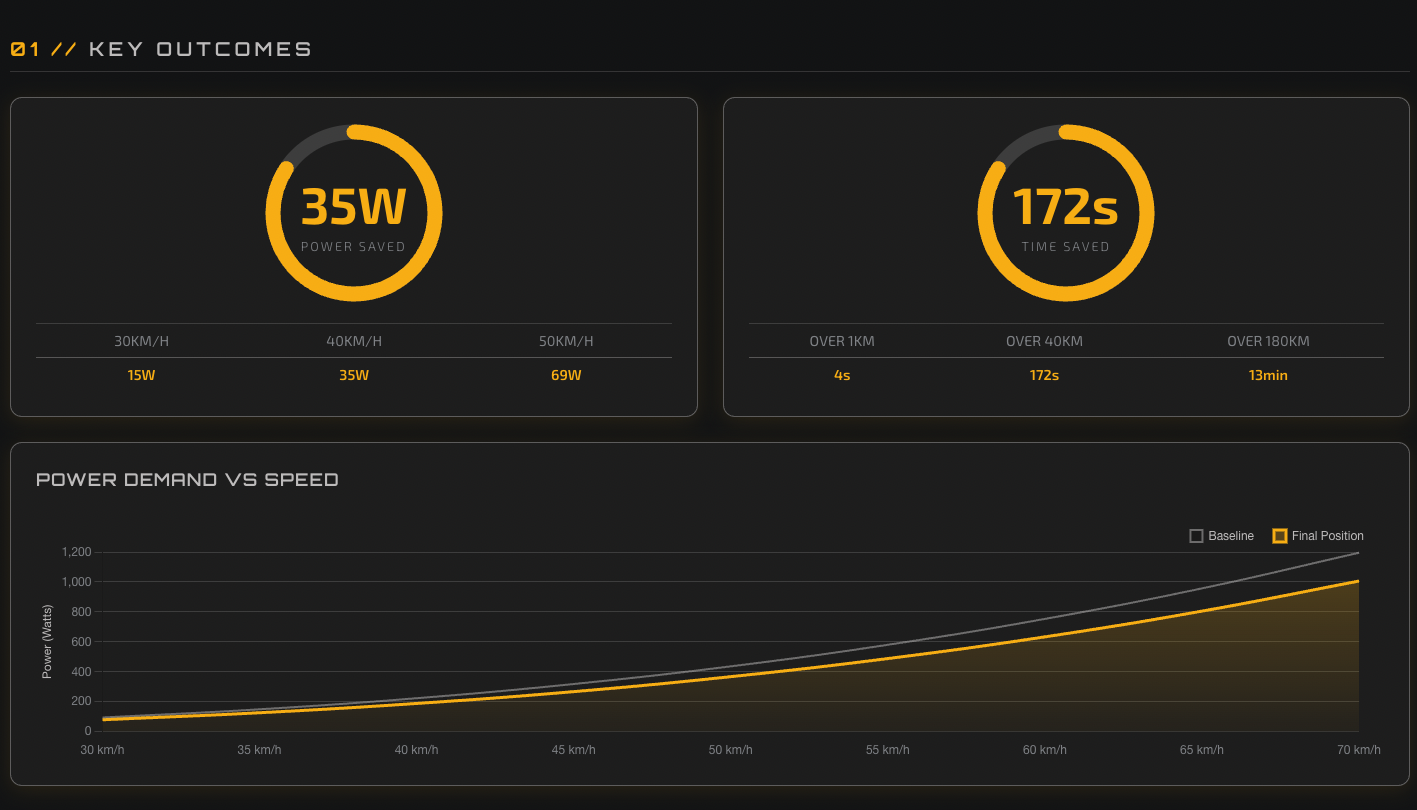

After running the full simulation, these were the main conclusions the AiRO app was able to establish:

“Starting from his baseline position of 0.271 m², we systematically tested five configurations, keeping bike coordinates constant while making meaningful body position changes,” read my final fit analysis that was sent to me after the test.

The results were striking: while adding a helmet marginally increased drag to 0.273 m² (costing 1 watt), lowering hand position proved significantly worse at 0.277 m² (costing 5 watts).

"The lower hands position was particularly instructive: despite seeming aerodynamic, it exposed more arm surface area, and since the arms account for roughly 25% of total drag, this single change significantly compromised overall efficiency.

Then came the breakthrough positions: the aero tuck dropped CdA to 0.237 m², saving 28 watts at 40 km/h, while the lower head position achieved 0.228 m²—a remarkable 15.8% reduction from baseline.

“At 40 km/h over a 40km time trial, the lower head position saves 173 seconds (nearly 3 minutes) and 37 watts compared to baseline, or close to 6 minutes over an Ironman bike leg.”

Overall AiRO fit output

Now, that optimal position is not a position I can hold for a long time. Twenty minutes, max. Yet, that’s not the goal. Since this isn’t for time trials, it is more important to have an A and B position, one more aggressive, one more relaxing, to give me the best mix of sustainable power and overall aerodynamics. All of this is easy to test and reinforce with the system. There are also elements, like dropping my head, that I can do at any point to stack seconds gained across a race day.

For me, a huge takeaway beyond those positional insights was what it meant for future purchasing decisions. A 130-140mm stem is certainly on the short-term list, but it could be more than that. My next bike will likely be a 58cm frame and not a 56cm frame. Or, counterintuitively, I might need to find the right all-road bike rather than an aero bike to get into the aero-optimised position. Soon, I will also be able to model different helmets in the app, without even trying them on, to make sure I am getting the right one for my body without having to buy multiples and then test them later.

“You can become much more aggressive with your position, and you can trade a little bit of comfort for some power or some drag reductions,” Stover said, “but you can't do that with an Iron Man or gravel. So you really have to think about this as reducing drag, but also increasing comfort at the same time, and increasing power.”

Overall, my bike fit fell short of its full potential, partly from my bike’s limitations and partly due to my inability to hold that optimised position for long periods of time. The fit was also conducted on a road bike rather than on a time trial, which is where I spend most of my solo riding time and where fit data tends to be more impactful. In retrospect, bringing my gravel bike in might have been more effective. However, with bike handling more important off-road, I am more hesitant to completely optimize around aerodynamics on gravel.

Still, many of the insights can be transferred, especially in key moments when I am road racing and I do hit the front. It is all concrete to me in a way it has never been before.

You can read my full AiRO report here!

Logan Jones-Wilkins is a writer and reporter based out of the southwest of the United States. As a writer, he has covered cycling extensively for the past year and has extensive experience as a racer in gravel and road. He has a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Richmond and enjoys all kinds of sports, ranging from the extreme to the endemic. Nevertheless, cycling was his first love and remains the main topic bouncing around his mind at any moment.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.