Road bike geometry explained: how to choose a bike that suits you

Cycling culture is full of little idiosyncrasies. Some of them we love and respect, like the fact that a water bottle is a water bottle in all walks of life except when on a bicycle. Others can be infuriating - and the inconsistencies within geometry charts definitely fall into the latter category.

The geometry of a bike is hugely important when it comes to selection. As bike fitter at Soigneur in London, Tim Allen puts it, “geometry creates a bike’s personality.”

However, since every brand seems to have its own secret squirrel method of displaying and itemising geo, actually putting the numbers to good use can be confusing.

Here are the important numbers to look out for.

Stack and reach

In the past, brands would leave potential customers to determine how long and low, or short and high, a bike was based upon the top tube and headtube length. Then, stack and reach arrived and the vast majority manufacturers have incorporated the standard.

Stack is the vertical distance from the centre of the bottom bracket to the mid point at the head tube. Reach is the horizontal distance from the centre of the bottom bracket to the middle of the head tube.

These measurements will help you determine if the bike will put you into a racer's position with a long reach and short stack (aggressive), or one which will be comfortable for long, all-day rides (endurance/relaxed) thanks to a short reach and high stack.

As an example, a raceySpecialized S-Works Venge in a size 54 has a stack of 534mm and a reach of 387mm. Comparatively, the endurance readyS-Works Roubaix in the same size has a stack of 585mm and reach of 375mm.

>>> Is your bike set-up too aggressive?

"The new standard of stack and reach is the easiest way to start comparing if a bike is going to be long and low or high and short. When I'm looking at whether a frame geometry is going to fit with what I want for a client, they’re going to be the most important measurements.

"The old school measurements like top tube length and head tube length, are a bit outdated and misleading. When it comes to the top tube - the angle of the head tube and seat tube will have an impact – if a bike has a 55cm top tube, and a 70º angle, and another has a 73.5º angle, effectively the reach on the 73.5º bike is going to be longer."

Head tube length is equally variable.

"Once, a standard fork length was 370mm, and you could compare head tube lengths. Now, more bikes have different fork lengths. A gravel bike or endurance bike that’s got disc brakes and more tyre clearance will have a longer fork to cater for that, so the head tube is going to become shorter but it doesn't increase the drop," Allen comments.

If you're buying a built bike, it's important to consider the effect the specced components will have, especially with the likes of integrated bar/stem arrangements where a swap isn't cheap.

"Standard handlebar reach is around 75mm, but you can get handlebars that are as long as 110mm. That's a big difference. And obviously stem length."

He uses the example of the Cayon Aeroad and Trek Madone in H1.5 fit. The Aeroad in a Large comes with a reach of 403mm, vs the Madone's 391mm in a 56. However, the Madone uses much longer reach handlebars, a factor that wouldn't be immediately obvious from the geo charts.

Though sometimes expensive, handlebars can be swapped. Stack is less easy to manipulate without making changes which can negatively affect handling.

"Usually the most limiting factor is the stack, you've usually only got around 35mm to play with there, without flipping the stem" Allen says.

Stack and reach sits on a sliding scale, finding what suits you is something you can perfect by trying a range of bikes, and knowing which numbers suit you - or of course booking in for a pre-purchase fit.

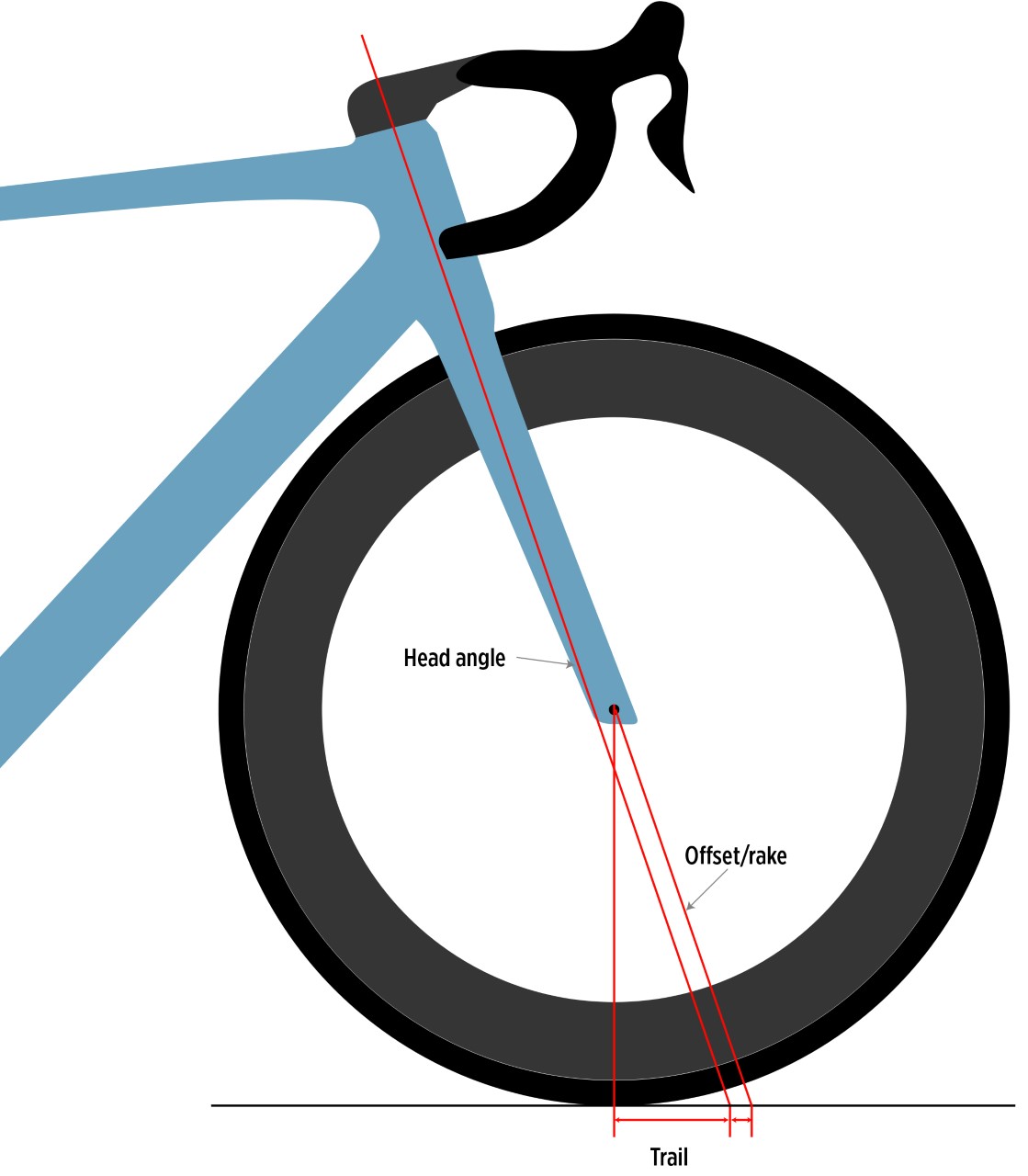

Fork offset, trail and head angle

Fork offset (sometimes called rake), trail and head angle areintrinsically intertwined.

Offset/rake is how far the front axle (hub) is offset from the steering axis. Trail is the distance between the tyre's contact patch with the ground and where the head angle line hits the floor. Head angle is the angle at which a line would travel through from the head tube to the steering axis, to hit the floor.

If that's closer to mud than crystal in terms of clearness, it's ok - what matters is the effect.

"Fork trail is probably the easiest number to look at, if you want to answer the question: 'is this a race bike or an endurance bike'?"

"The numbers don't differ hugely, but small changes made define how the bike is going to handle," Allen says. "The smaller the fork trail number, the faster the bike is going to respond. The number is the relationship between the head tube angle, and the fork offset - so how far the axle of the fork sits out from the crown of the fork.

"The smaller that gap, the lighter it will be to turn the wheel, and the more responsive the bike will be at speed. If you were to extend that fork trail, it will slow handling down and make the bike more stable."

When it comes to racey handling, expect a fork trail of 55 to 59mm and a steep head angle of72.5-73º. An endurance bike will have a fork trail of over 60mm and a slack head angle,closer to 71.5º. The differences are seemingly minute, but will show themselves in the ride.

The only exception to this is on very small bikes, where the trail sometimes has to be increased to prevent toe overlap. This is clear within the Specialized Venge charts where a size 49 has a trail of 63mm and a 52 cuts it down to 58mm, down to 52mm on a size 61cm.

Some manufacturers, such as Canyon, have opted to reduce wheel size to counter this, dropping to a 650b wheel, and thus offering consistency in the fork trail across the size range.

Seat tube angle

Seat tube angle is simply the angle at which the seat tube sits, and it will have implications on set up.

If the angle is too slack, on larger bikes the seat tube will extend too far backwards, which Allen says presents problems when fitting riders to bikes. So if you're a tall rider, it's worth bearing this in mind.

"Seat tube angle will affect where you're going to position the saddle. It's one of those standards that's never really changed, if you look at a small bike it will have quite a steep seat tube angle, 74-74.5º degrees. As the bike gets bigger that seat tube angle tends to get slacker, even down to as much as 72.5º or 72º degrees on the biggest bikes.

"A lot of the time it means on a larger bike I can't get the saddle far enough forwards, because the seat tube has gone way too far back. Even with an inline seat post. On smaller bikes I tend to find it a lot better, at 74º degrees you can usually get the saddle very central on the rail."

He adds that some manufacturers have remedied this, Canyon for example uses a seat angle of 73.5º, on all bikes in all sizes.

Seat tube angle is rarely considered as a major factor when it comes to handling or ride style, though Allen does comment that a slacker seat tube angle may add to compliance, leaving more length for flex.

Wheelbase and bottom bracket drop

Wheelbase is another marker which helps determine the difference between quick footed handling and stability.

The measurement comes simply from the distance between the centres of both wheels. It can be represented in two parts: rear centre (from the centre of the rear wheel axle to the bottom bracket) and front centre (from the centre of the BB to the centre of the front wheel axle), though few brands provide this level of detail.

"Wheelbase will have a direct effect on handling, you shorten it and the quicker its turning circle will be. If you stretch the two wheels out it'll have a longer turning circle, which will feel more stable at lower speeds.

"If you're considering a bike to go cruising through the countryside you'll want that stability, but if you're going to race you want to be able to get through corners fast."

Touring bikes and adventure bikes then will have longer wheelbases, with endurance bikes in the middle and race bikes at the other end of the scale. As an example, a size 54 Specialized Roubaix has a wheelbase of 987mm vs 978 for a Venge.

Of course, the wheelbase of an all round smaller bike will be shorter, so a rider who wants a really agile bike might choose a smaller bike, using a longer stem and handlebars to get the reach they want.

Another element that will influence stability is bottom bracket drop - how far the BB drops down from the two wheel axles. This standard has changed over time, with factors such as larger tyres playing a role.

"The standard on a road bike used to be 70mm. Partly to allow for plenty of clearance in corners, though you can manipulate this with shorter cranks. You'll find on endurance bikes, the bottom bracket drop will be lower to add to stability, because you're lowering the centre of gravity," says Allen.

When designing race bikes, Allen has opted to spec shorter cranks for some riders, as low as 165 even for those close to 6ft in height. This allows him to drop the BB and thus provide the best of both worlds with stability and clearance, whilst also letting the rider get low and aerodynamic without closing the hip angle.

Bottom bracket drop and chainstay length are two factors that you’d expect to change throughout the size range of a model.

“Identical bottom bracket heights across the size range are a red flag, as are identical chainstay lengths across the size range. That means that the designer hasn’t really taken into account how centre of gravity changes as the bike gets bigger and smaller. Obviously if you’ve got a short chainstay on a large frame you’ve put the rider’s centre of gravity further back than on a smaller frame,” says Bowman Cycles’ Neil Webb.

“Chainstays that are the same across the size range are usually a sign of a brand saving money by using one chainstay mould. This is particularly common on the new dropped seat stay bikes we’re seeing a lot of – because the whole rear end is then made in a single mould.”

How do brands go about designing geometry?

We asked Giant’s Design Manager Erik Klemm, to describe how the team at the Taiwanese brand goes about creating a brand new geometry.

“We start by leveraging our pro racers and global partners to allow us to reach our target riders and obtain the correct insights. We observe the market and summarize riding postures, and then begin the geometry draft.

“Initial geometry points revolve around the bottom-bracket height, wheel size and suspension requirements. Head angles and fork offsets come next, allowing us to assign nimble or stable steering. Then, we define other attributes like trunk angle, shoulder angle, knee angle – relating to the rider style and dimensions on a particular bike.

“We then build the prototypes and modify the geometry after field tests. After the process of trial and error, we can define true geometries for the brand new bikes.”

“The Designer and Engineers working on new designs use a set geometry that has been agreed upon by our merchandising team. They actually have several geometries they must manage since we create multiple sized frames for each model. That data is transferred from our product planning sheet into our Siemens NX CAD software. This provides a foundation for the designer to work off of. Think of it like a skeleton 2D sketch on a particular layer.

“From this, all the 3D surfacing and shaping is based. If updates to the geometry are made mid-project, the software can usually update the shaping to reflect these changes. We actually build mathematical excel charts that allow the designer to plug this into the software. This particularly comes in handy when we need to propagate numerous sizes of frames. The software is able to reshape the frame based on these new numbers without starting from scratch.”

The distinction between fit and handling

Neil Webb is the Founder, MD and Head of Product at British brand Bowman Cycles – he says that each customer is guided through the process, which always starts with handling.

>>> Road bike size guide: how to choose a bike that fits you

“There’s two sides to geometry – geometry for fit, and geometry for handling. They’re exceptionally separate conversations.

“If you’re deciding on a new bike, start by looking at it from a handling perspective. Compare the bottom bracket height, wheelbase, and the relationship between the front centre and the chainstays with a bike you know you like. If those are similar, then head angle, fork rake and trail are similar, you will know it will be a similar feeling bike.

“Once you’ve decided on a model, then you start looking at what size you need.

“With any Bowman customer that comes to us, what we want to do is get them on a bike that handles how it’s designed to handle. Of course, a customer could ride a 56cm frame with a 140cm stem on it, but you can only put so much weight over the front end before it stops handling as well as it was designed to. We start by making sure they’re looking at the right frame for their goal, and then also trying to get the right size from for them, based on what we wanted to achieve from a design perspective in terms of weight balance.”

There are some great tools that you can use to help you compare fits and geometry – such as bikeinsights.com.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.