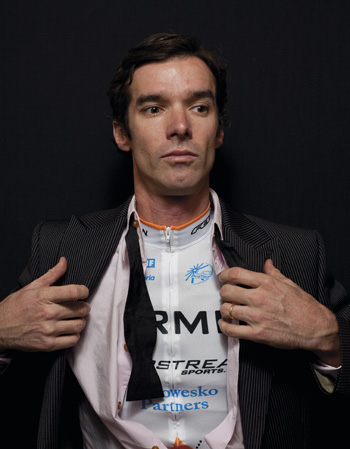

David Millar Interview: Millar's Tale

“You end up in this success-driven, materialistic world. I escaped that by losing everything”

After a promising early career, David Millar reached his lowest ebb in 2004 when he was slapped with a doping ban. Six years on, the Garmin rider explains how all that was part of the process that has made him the rider — and the man — he is today.

Words Edward Pickering

Photos Richard Baybutt, Graham Watson, James Purssell

I was watching the Tour de France in 2005, just being a fan again. I thought, you’re a fucking idiot. You’re a bike fan who gets to ride the Tour de France.”

David Millar’s description of his epiphany is direct, reflexive, foul-mouthed and self-referential, a bit like Millar himself. He’s grown up, and had to do so in a very public way, a difficult thing to do when you live your life in the hermetically sealed bubble of professional sport. And while six long years have passed since the worst dinner of his life that evening in Biarritz — a starter of arrest, a main course of ransacked house, and a dessert of police interrogation — the past will always be with him.

He’s learned to live with it. He still travels the world with his racing bike, team kit and suitcase. Plus the baggage, and, you’d think, regret.

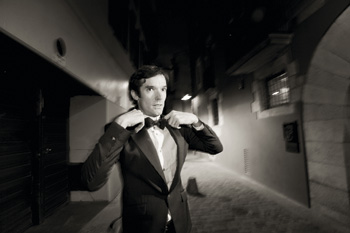

But this is the paradox of David Millar’s life. Nobody could undergo the public humiliation and shame that he had to without ruing the day he ever looked at an EPO-filled needle. But important, life-changing things have happened to him since, which wouldn’t have happened if he hadn’t doped. He’s become a leading figure in Garmin — the team commonly held to be the most transparently clean in the peloton. He sits on the athletes’ panel of WADA. And most importantly, he’s got married, to Nicole. He’s moved a few miles out of Girona into a rented farmhouse, with nothing but fields and forest around him. He’s got a dog. He’s even, God forbid, talking about growing vegetables some time down the line.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“Professionally, I’m happy where I am. Yet I am forever living with the mistakes of my past, and it’s never going to go away as long as I’m a professional cyclist,”

Millar says.

“On the personal side, everything is wonderful. I’m married. I’m very lucky to have a good, stable home life, which I’ve never really had. But that has been one benefit of everything that has happened to me. That’s a positive of getting caught, and getting out of that spiral I was in.

“It allowed me to reboot my life. There’s no way I’d be here now, if none of that stuff had happened, and if I’d continued the linear development I was

on as a young athlete, I wouldn’t have found such happiness. You end up in this eternal, success-driven, materialistic world. I escaped that by losing everything and having to start again. I met Nicole when I had nothing.”

We’ve only been talking for a couple of minutes. Cycle Sport was going to save the deep stuff for later in the interview, but there’s not only an elephant in the room, it’s trumpeting loudly and slapping us around the head with its trunk. He must surely regret having doped, yet it ultimately led to stability and contentment. Does Millar realise what he’s saying?

“I know,” he admits.

“But I’m in flux. It’s an odd place to be. It’s thanks to my doping that I’ve found such happiness personally. I’ve escaped the pattern I was in. But I also escaped the pattern I was in before I was even doping, and I’m going to benefit from that for the majority of my life.

“I regret doping and always will. But there has been a silver lining.”

Lone ranger

In a boring Tour de France last year, one image of David Millar stands out. His lone escape, through the huge, canyon-like boulevards of Barcelona, where he came within a kilometre of a stage win, looked more like a painting than a bike race.

“It was just me being emotional,” he says of his attack.

“I was exhausted, but we got on this stretch of road early in the stage, about 25 kilometres long, on a corniche. I knew it instantly — we use it to train in winter. It’s one of the most beautiful roads.

“Everyone was going mental. We were 35 or 40 kilometres into the stage and we were still a group, so everyone knew it

was going to go soon. I just got carried away, racing on this road that me and Christian [Vande Velde] train on. It was like being a kid.

“I sat there, cold and calculated, and waited. I knew the road, and I knew they couldn’t keep going as fast as they were. It was blowing up everywhere. I was seeing the best riders in the world, their legs falling off. And when they stopped going hard, I went as hard as I could.

“Sylvain Chavanel, Stéphane Auge came across, we looked at each other, and thought, we’ve made a big mistake.”

Millar felt terrible all the way through the stage, until a second wind came 30 kilometres out of Barcelona.

“It was very powerful coming into Barcelona. Wide roads, and people as far as the eye could see. The noise was a cacophony. Barcelona was very visceral in that sense — I was focused on the effort, but very aware of my surroundings. This was special. It was the kind of cycling I love. I had no chance, yet nothing to lose. It was cycling at its purest — me against the odds.”

The odds won in the end. Millar was caught a kilometre from the line, passed and forgotten by the race.

“When they caught me, there were only 40 guys left and they looked terrible. I thought, well that’s good — I haven’t won, but I’ve destroyed the Tour de France peloton. It was good. They were battered.

“And it doesn’t matter that I didn’t win. If I had, the important memories and motivations wouldn’t be any different. Winning wouldn’t have changed any of the good stuff I got from that day.”

Cycling’s spokesman

Millar is a lightning rod for opinion in the cycling world. Some of the biggest issues facing cycling today are played out across his career, and what he says. It’s not just the doping issue. Millar is also a passionate believer in sport for sport’s sake, a position which sets him diametrically opposite one of the biggest influences in cycling, and the peloton’s other lightning rod, Lance Armstrong.

Millar’s attack into Barcelona would have made Lance Armstrong choke on his bidon. Show Lance Armstrong a fruitless attack, and Lance Armstrong will show you a loser.

Ironically, Millar and Armstrong used to be good friends. Not any more, if we read between the lines of his description of their current relationship.

“It’s complex,” says Millar.

Go on.

“It’s just complex.”

But Millar is far more willing to talk about Alberto Contador, and in doing so, opens up about Armstrong.

“I feel for Contador. I think that by the time he ends his career, he’ll be one of the greatest ever cyclists, and Johan Bruyneel [Contador’s manager at Astana in 2009] treated him like dirt.

“As soon as Armstrong came back, suddenly it was like Contador was a 23-year-old neo pro. And I think it’s a testament to Contador, not just as an athlete, but as a man, to have handled it the way he did. He went up against Lance Armstrong, not just physically, but psychologically, and came up the winner. Nobody ever did that. In fact, it didn’t affect him in the slightest. It made him better.”

When Cycle Sport interviewed Armstrong in late 2008, he was far less keen to talk about the Slipstream team (Garmin’s old name) than Columbia. Both had been held up as examples of clean transparency, but Armstrong always veered towards talking about Columbia’s winning model.

Manager Jonathan Vaughters has always made it explicit that winning is a bonus, not the aim — riding well, plus publicising the personalities of the riders, being extremely open with the press and gaining good publicity for sponsors through different avenues is what they do. There are also rumours that of all the sponsors in the ProTour, Garmin get the best value for money from their sponsorship, even more than Columbia, who win far more races.

“There’s no direct conflict with Armstrong. He doesn’t say anything bad about us, but just avoids the subject,” Millar says.

“We’ve had an interesting time — been friends, drifted apart, it’s been odd for us. He’s not very keen on Jonathan. Lance puts things in boxes, and as soon as it became clear I got on very well with Jonathan, I was put in the Jonathan box.

“I enjoy chatting to Lance. But we’ve got too much history. Yeah. No...” Millar trails off.

Bradley’s wingman

Millar’s 2009 Tour wasn’t just about a single lone attack being snuffed out in the Barcelona rain. He was one of the most important domestiques in the entire race.

At the foot of two of the most crucial climbs of the Tour — Verbier and Ventoux — Millar played the consummate team-mate, leading a raging bunch in both instances in order that his leader Bradley Wiggins could start the climbs in the best possible position.

“I’m a domestique now. Christian [Vande Velde] taught me a lot about that, because it was always his role. He was a lieutenant to the leaders, so I learned from the best. It can be something to take a lot of gratification from, and it was a respectful thing to do,” he says.

Millar’s efforts at Verbier and Ventoux were almost invisible, but crucial, and demonstrated experience and strength. Every team wants to be on the front at the bottom of an important climb, yet only one can do so. Millar was effectively in charge of the peloton at these moments.

His efforts gained extra significance during the off season when he got involved in a small war of words with his ex-team leader Wiggins, following his transfer to Sky. Millar asserted that Garmin had soul and understood the sport, while Wiggins mockingly wondered on Twitter how Sky could become part of the fabric of the sport.

Again, Millar finds himself occupying a position diametrically opposed to something, and this time, it’s the Sky team.

“I was disappointed when Wiggins left. But Sky saw a window of opportunity to come in and make cycling a more professional, cutting-edge sport,” he says.

“It’s a shame, but Brad had no choice, the amount they were offering, and the package. Maybe he had a horse’s head in his bed.”

The big D

Millar’s doping issue will always polarise fans. Some will never forgive Millar for what he did. Others are affronted by the outspoken statements he makes about the fight against doping.

But, like everything in David Millar’s life, there’s a paradox at work. He cheated, and lied about it. But it’s just possible that David Millar will do more for the anti-doping movement than most other riders.

This does not sit well with everybody, but Millar recognises that the subject has to be talked about, and talked about some more. While the omerta, the law of silence, held sway, nothing positive could be done against doping. Millar’s first punishment was the two-year ban. The second was the burden of responsibility of being the public face of an ugly and drawn-out war. Millar also represents what he believes is the basic ethical principle of a second chance.

“Obviously, I’ve got personal reasons,” he says. “But it works for some people.”

Millar’s choice of words is interesting and deliberate. “Some people” obviously includes himself, so Cycle Sport asks him about three specific, and very differing examples of riders who have been given second chances.

In 2005, Ivan Basso, Alexandre Vinokourov and Alejandro Valverde were three of the biggest names in the peloton. Basso was going to inherit Lance Armstrong’s Tour de France crown. Vinokourov was the indomitable attacker, the thorn in the side of the Tour contenders. Valverde had outsprinted Armstrong himself at Courchevel.

“I respect Ivan Basso. He’s been contrite, and I believe very much that he’s doing it properly now. He’s paid for his mistakes, and he wants to prove that he won’t make them again,” says Millar.

“But Vinokourov is at the other end of the scale. He’ll never be the same rider again, and he doesn’t treat the peloton with respect, so he doesn’t get treated with respect back. There’s zero respect for Vinokourov in the peloton.”

Valverde, according to Millar, falls between the gaps.

“Valverde is a tragedy of the system,” he says. “He was possibly into it up to his neck, but we know the system is at fault with him. He’s a phenomenal bike rider, but the tragedy is that he’ll never be a great because he will always have that cloud hanging over him.

“Unfortunately, it’s a minority of people who are contrite and feel a responsibility for their mistakes and make amends,” he says.

Whether Millar has made amends or not is up to individual fans to decide. In many ways, he’s been extremely lucky, both in finding stability in his personal life, and in his path crossing with that of Jonathan Vaughters when the Slipstream team was just expanding its ambitions into the ProTour races.

“I can’t even imagine where I’d be without that having happened,” he admits.

“Second chances can sometimes make something better than it was before.”

David Millar looks at me, and I look back at him. After an hour and a half of talking, we’re right back where we started.