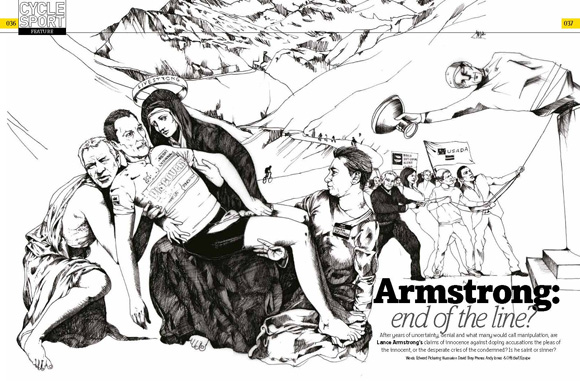

Lance Armstrong: the end

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Resolution is fast approaching in the most controversial story in cycling. But there are still many questions to be answered.

Words by Edward Pickering

Thursday July 5, 2012. This article appears in the current edition of Cycle Sport magazine

A few days after interviewing Lance Armstrong in Austin, Texas, for this magazine on the occasion of his comeback, in late 2008, I got The Call.

It’s not unusual for me to contact interviewees after we’ve spoken. In the course of transcribing an interview and writing a feature, it’s sometimes necessary to follow up and check a couple of facts, or explore a line of inquiry that we didn’t have time for.

This one was different.

Number withheld.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“Hey Ed, it’s Lance Armstrong,” said the voice at the other end. “How’s your kid?”

I fought the urge to go upstairs and check he was still asleep in his cot. Armstrong hadn’t called to make small talk, however. He wanted to discuss our interview, although to describe it as a discussion would be to overplay my part in the conversation.

“Your questions came from a very negative place,” he informed me.

I like to think I gave as good as I got. Armstrong chewed me out for obsessing about doping, while I lectured him about the sport needing to be built on ethical foundations and integrity, or it would have no meaning at all. This went on for a good half hour.

Then things turned a bit weird.

“OK then, if I cheated to win all those Tours, how did I do it?” Armstrong asked, challenge in his voice.

I was gobsmacked. The situation reminded me of OJ Simpson’s book If I did it. I was silent for a long time while my amazement found expression.

“Well, I don’t know,” was the best I could manage.

***

The letter that the United States Anti-Doping Agency recently sent to Lance Armstrong, his manager Johan Bruyneel and four others (Michele Ferrari, Pedro Celaya, Luis Garcia del Moral and Pepe Marti), is as incendiary a communication as cycling has ever seen. On June 12, USADA informed the six recipients of the letter that formal action was being opened against them for violations of the UCI’s anti-doping rules. Each would be charged with the following five rule violations:

- Possession of prohibited substances

- Trafficking of prohibited substances

- Administration of prohibited substances

- Aiding, abetting and complicity in covering up the rule violations

- Aggravating circumstances

And Armstrong, the only rider in the six, was also accused of:

- Use of prohibited substances

There were a couple of moments of accidental levity. We were reminded that the slang for EPO within the anglophone peloton was “Edgar Allen Poe”, while testosterone was referred to as “oil”. In a specifically, and typically, Italian twist, it was said that Michele Ferrari, also one of the six, mixed testosterone with olive oil. Groundnut oil just wouldn’t have been the same.

But the allegations were extremely serious. USADA were accusing six individuals of no less than a conspiracy stretching over more than a decade, going back to 1998. (The World Anti-Doping Agency’s statute of limitations is eight years, but USADA’s argument is that the activities occurred within the last eight years and that evidence of wrongdoing going back a further six years is relevant to the case).

Armstrong himself would have to defend himself on multiple fronts – many ex-team-mates and acquaintances of the Texan will testify to his guilt, the unresolved issue of an alleged positive EPO test at the 2001 Tour of Switzerland, said to have been subsequently covered up, would be investigated, and USADA also think they can see data consistent with blood manipulation from tests done after Armstrong’s comeback, in 2009 and 2010.

Armstrong was given 10 days to respond, with the case then going to a review board to decide whether to open charges, or to close the case.

Note: since publication of the original article, the review board has given the go-ahead for USADA to open charges.

Armstrong did what comes so naturally to him, he doesn’t even understand that there might be another way: he kicked back, hard. On his website, he rehearsed rebuttals familiar to all those who follow his career: the accusations were motivated by spite. He’d never tested positive.

“I have competed as an endurance athlete for 25 years with no spike in performance,” he said.

***

Armstrong’s a genius with language. He has a gift for concocting memorable phrases seemingly off the cuff, and if he goes into politics, heaven help his opponents in debates.

His denials have always sounded plausible, as long as you don’t think about them too hard, like some of his more fervent supporters. But examine them, and you’ll notice that he often redefines the parameters of the accusation. Rather than deny doping, in the past, he’s wheeled out the “never tested positive” line: it’s a guaranteed floor-filler. He calls the tune, and his supporters dance to it.

This is problematic, because, as we all know, he has tested positive. Once, officially, at the Tour de France in 1999, when a backdated therapeutic use exemption certificate was produced after corticosteroids appeared in his sample. (Oddly, when I interviewed him, he seemed to forget himself and claimed never to have had a TUE in his career – when I mentioned the 1999 cortisone TUE, he relented, saying, “well, there was the cortisone”). He’s also unofficially tested positive, after samples taken in 1999 allegedly tested positive for EPO in the course of the development of a test for the substance. An enterprising L’Equipe journalist managed to get hold of a match between the code numbers for the samples, and for the riders’ names.

But never mind that – the issue is not whether these unsanctionable offences are concrete evidence of his guilt, but that he has shifted the attention away from whether he actually doped or not.

Instead of proclaiming his innocence, he merely redefines innocence as simply not having been caught,

And that’s why he was clever to point out that there had been no spike in his performance. There hasn’t. His athletic performances were more of a plateau, and his accusers certainly think they know how he got to that level, but that’s not the point. Armstrong first planted the seed in the mind of the reader that spikes in performance are suspicious (and, yes, they can be), and then cheerfully pointed out that he hadn’t had one. Move along now, nothing to see here.

***

The success of USADA’s case will be based on their ability to build enough evidence to support a “non-analytical positive” - proof of doping that doesn’t rely on a positive test. Although there may be some crossover in terms of evidence that was gathered by the recently-closed federal criminal investigation led by Jeff Novitsky, USADA have been quite clear that this is a separate case. USADA’s head, Travis Tygart co-operated with Novitsky’s investigation, but apparently the evidence has not yet been shared.

USADA’s burden of proof is lower than that in a federal case. Novitsky’s failure to secure an indictment shouldn’t necessarily be seen as an indication the USADA case won’t find Armstrong guilty.

Will USADA be able to secure a non-analytical positive? And if they do, will it cause the fall of Lance Armstrong?

All USADA can do is strip him of his Tour wins and ban him from competition. He’s retired from cycling, so it won’t make much difference, and there are many previous Tour winners whose disqualification wouldn’t make much difference anyway, because the guy in second was also doped to the gills. Stripping Armstrong of his Tour wins merely leads to the parlour game of finding the first clean rider behind him.

There will be financial ramifications – Armstrong collected a five million dollar bonus from the SCA Promotions insurance company for his winning streak at the Tour, and given that they only handed it over after a protracted legal battle following the 2005 L’Equipe doping allegations, they’re likely to want it back. That’s still a lot less intimidating than what faced him when the criminal investigation was still going on – prison.

Edit: five million dollars was the figure quoted by the New York Times, but this only refers to the final Tour win. In total, it is believed that SCA paid out 9.5 million dollars for all of Armstrong's Tour wins, plus lawyers' fees also estimated between two and three million dollars.

But the real consequence for Armstrong may be far more serious. He can deal with admiration. He is also extremely comfortable with hate – he feeds off it. But Lance Armstrong’s worst nightmare is irrelevance. If he’s found guilty, everything he has built on the foundations of his success as a cyclist will be brought into question.

What’s noticeable from the reaction to the latest investigation is how willing more and more people seem to be to speak out against him –the “more than 10 cyclists” cited in USADA’s letter to the Armstrong six, the American press, fans in general.

Armstrong is a natural bully. And he relies on the silent and fearful acquiescence of those around him to get away with it. He bullied Filippo Simeoni live on television during the 2004 Tour. He bullied Christophe Bassons, during the 1999 Tour. He’s bullied journalists in press conferences. He tried to bully me over the telephone. His admirers would have that he bullied cancer into submission.

Witness testimony is the key to USADA’s case. The Tour of Switzerland positive, and the 2009-2010 blood data are relevant in USADA’s eyes, otherwise they wouldn’t have cited them in the letter. But the case against Armstrong will hinge on people who were formerly fearful of turning against him choosing to do so.

Few people know exactly who the “more than 10” cyclists or the team employees who will testify are. You would have to have been living in a cave for the last 10 years not to know which individuals went on the record in David Walsh’s book LA Confidential, or which ex-teammates who have tested positive and turned against Armstrong, have also gone on the record. Those people will certainly be involved.

Armstrong’s tactic against people like Floyd Landis or Tyler Hamilton has been to portray them as bitter cheaters. Armstrong has always done this – he plays the man, not the ball. (In an astonishing display of chutzpah, his lawyers cited a passage from Landis’s book Positively False in their response to USADA – this is the book Landis wrote when he was in the initial stages of denial about having cheated during his cycling career).

But it’s also possible some people who can’t easily be described as bitter, or cheats, have spoken up as well.

Coincidentally with the USADA letter being sent, ESPN reported that four senior American riders had withdrawn themselves from consideration for the London Olympic cycling team. All had been former team-mates of Armstrong. Christian Vande Velde, Levi Leipheimer, David Zabriskie and George Hincapie were the four.

Et tu George? Then fall Armstrong.

***

That an entire generation of cycling has turned out to be deeply tainted is beyond doubt. From the early 1990s through to really quite recently, you have to ask yourself how big race winners did it. Some have tested positive, or have confessed to doping (when trotting out the “never tested positive” line, it’s worth considering that David Millar, Ivan Basso, Jan Ullrich and Bjarne Riis, to take a few examples, never tested positive).

Blood boosting, either by transfusions or ‘Edgar Allen Poe’, give such an unfair advantage to some riders that what results from their usage is not sport. Apart from the fact that such high climbing speeds as were being achieved from the mid-1990s onwards effectively deaden any tactical interest or finesse, these doping techniques aren’t democratic. It’s not the case that the same hierarchy exists with doped riders and non-doped riders – we often hear that it doesn’t matter if everybody is cheating because the strongest riders win anyway. Some riders gain more of an advantage than others from blood manipulation, Bjarne Riis being just one striking example.

There are differing ways of dealing with the existence of the tainted generation. Some, very few these days, still deny it ever existed. It was just a few bad apples, they say. I’m not going to waste ink on explaining why this attitude is so destructive to cycling, but it would be much simpler to describe the peloton of the late 1990s and early 2000s as having a few good apples among an EU food mountain of bad ones.

Others are happy to acknowledge that it existed, but feel it would be best to draw a line under it and move on. While an amnesty sounds appealing for the wellbeing of the sport, it sends the message that as long as you didn’t get caught, it’s fine. If that’s the message cycling wants to send to my children, I’ll direct them towards other activities. Remember that lives have been lost in the turmoil surrounding doping in cycling.

The only other option is full catharsis. Cycling needs to lance the boil.

And the tainted generation have to be the ones to do this. Too many people working in cycling today have secrets in their pasts which might compromise their integrity. Many have privately renounced their past, including individuals who have done extremely well in team management or other aspects of the sport, and whose success is partly down to the contacts and reputations they gained as riders. Putting up a nice building on shaky foundations is bad architectural practice.

This is where the USADA witnesses come in. They’ve been granted anonymity in the process. “USADA sought to give riders an opportunity to be a part of the solution in moving cycling forward by being truthful and honest regarding their past experiences with doping in cycling,” the letter stated. Armstrong’s lawyers predictably made hay with this. “

These riders’ testimonies will be key to the case against Armstrong, but their own debt to cycling doesn’t end with a resolution of the case. If he’s found guilty, they will be open to the accusation that there is one rule for one guilty person, and another for others. If he’s not, and they have testified truthfully against him, can they keep a clear conscience about continuing to hide the past while simultaneously enjoying success in a career that is built on their achievements in cycling?

Fans who have stood for hours in boiling sunshine or pouring rain to see their heroes, or bought the sponsor’s product, are owed an explanation. Come out and tell us what you did, why you understand it was wrong, and then we can get on with the sport.

***

Cycling fans are fairly used to the glacial pace of resolving doping issues – Alberto Contador tested positive in July 2010, and wasn’t sanctioned until February 2012. The Armstrong issue has been a backdrop to cycling for longer than many fans have even been following the sport.

Some of it will be played out in the court of public opinion, and some will be played out behind closed doors with lawyers, scientists and interested parties all arguing over the dots on the is and crosses on the ts.

But while this goes on, there’s something important that needs to be addressed: what Lance Armstrong did was impossible, or so improbable as to be virtually indistinguishable from impossible.

Michele Ferrari, Armstrong’s old coach and one of the six defendants in the USADA action, is on the record as talking about the Texan being able to express a sustained power output of 6.7 watts per kilogram of body weight when he was winning the Tour.

The late Aldo Sassi, who was respected as one of the best cycling coaches and whose reputation was spotless, concluded that a sustained 6.2 watts per kilo was probably the limit of human achievement under normal physiological conditions. Unpredictable variables, such as length of effort, would skew the numbers a little, but figures above 6 are freakish – the absolute limit of human achievement. 6.0 would win a Grand Tour these days (Sassi was quoted in the New York Times as saying that in the 2009 Giro, only one rider – Denis Menchov – got above six). 6.7 is impossible. It’s over 11 per cent more than 6.0, in an elite area of performance where the margins between riders are impossibly thin. It would be the equivalent of a long jumper jumping 9.93 metres (Mike Powell’s world record is 8.95 metres, and that was a pretty freakish jump).

Armstrong rode up Alpe d’Huez in 37-36 in the 2004 Tour de France, one second behind Marco Pantani’s record (although there is debate about the measurements based on where the climb actually starts and finishes). The fastest time last year was 41-21, by Samuel Sanchez. That’s a difference of just under 10 per cent.

The early 2000s were a different era, not just in cycling. The credit boom made us all think that some kind of new paradigm had been invented, one which would make us all richer. It turned out to be built on fresh air – maybe the background of our lives made some people believe more easily the myth that the laws of nature could be broken.

It makes us feel good to ascribe superhuman abilities to humans, to believe that force of will can drive special individuals to incredible achievements. It’s different this time. Armstrong fed this myth, by claiming to train harder. His fans claimed that his battle with cancer gave him the mental fortitude to ride away from his rivals.

But it’s a fairy tale. An individual with the right combination of genetic attributes and physiology might come along with an advantage of one or two per cent over the very best of his rivals. Five per cent? Human beings don’t work like that. 10 per cent or more? Sorry. You’re being lied to.

And that brings us back to the telephone call I received in late November, 2008.

Because I would like Lance Armstrong to answer his own question. How did he do what he did?

The USADA action is important, no matter how many aggressively-worded letters Armstrong’s lawyers send out trying to persuade us of the contrary. The witness testimony may be enough to result in Armstrong being found guilty. But cycling has its first chance in a generation to come to terms with its past, not just brush it under the carpet.

How did you do it, Lance?

Cycle Sport’s Tour village: All our Tour coverage, comment, analysis and banter.

Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/cyclesportmag

www.twitter.com/edwardpickering

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.