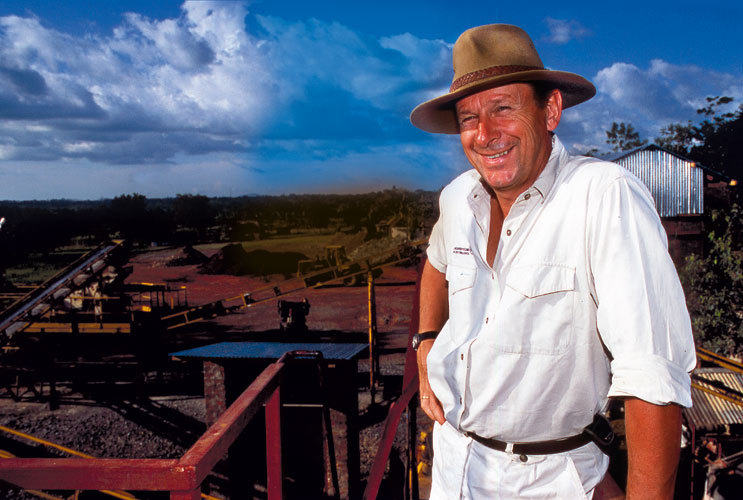

THE BIG INTERVIEW: PAUL SHERWEN

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Thirty years ago Paul Sherwen was a wet-behind-the-ears new pro, the first man in the second wave of British cyclists to establish themselves as part of the tough world of European road racing.

Today he is famous within the sport for his work with Phil Liggett, and for more than 20 years he has been part of the soundtrack to fabulous cycling moments. But there is a lot more to Widnes-born and African-raised Paul than that, as we found out.

CW: You made a meteoric rise through British cycling, from being almost unknown at the start of 1976 to a European pro in 1978. How did you do that?

PS: One of the factors was meeting a coach called Harold Nelson. He took me from a third-category rider to an international amateur. He guided me in lots of ways, but most important was that he instilled discipline in me, and he was ahead of his time as a trainer. Even in those days, well before anyone had heart-rate monitors, ?H?, as we called him, somehow knew intuitively how long we should train for at our lactic acid thresholds.

What was pro cycling like in 1978 compared to now?

PS: In the late Seventies and early Eighties cycling was having a bad time. The Tour de France could only get 10 or 11 teams, and six or seven of them were French. Races like Paris-Nice were hovering on the edge of extinction. The situation only really changed when Greg LeMond came to Europe.

How would you describe your riding abilities?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

PS: I was a pathetic climber but reasonable sprinter who enjoyed the northern Classics.

Would you have rather had your career when you did or have it now?

PS: I?ve no regrets. You can?t turn the clocks back and whatever I am now it is because I had my cycling career when I did. The TV commentating, for example, was only possible because I raced when I did. Plus, I think we enjoyed ourselves more than the riders do today. Bigger salaries have brought bigger responsibilities.

However, I wish that I had been able to live in a hillier area when I was a pro. It would have been better for training and for my development. I had to live in Lille, because my team were based in the north of France and I needed to be there for logistics reasons. Also, because of my scientific training (Sherwen has a degree from UMIST), I would have liked to have trained with the knowledge that the riders and trainers have today.

You live in Uganda where you have interests in a gold mine, and you balance that with your commentating work, how does the year pan out for you?

PS: I start off by going to Australia in January to commentate on the Tour Down Under with Phil, and in February we do the Tour of California. Then every weekend from March until June I travel from Uganda to New York to work on a programme called Cyclisme Sunday for the Versus network. We review the week and commentate on whatever race is on that Sunday.

I start out on Friday and go from Entebbe to Amsterdam, then Amsterdam to New York. I do the return trip every Monday and I?m at my desk on Tuesday morning. As well as the mining business I have another business that supplies logistics to the oil industry here. Oil has been discovered in Uganda and they expect to be pumping it out in 2009. After that it?s the Tour de France.

Do you ever get jet lagged?

PS: No, I won?t accept jet lag.

How does your partnership with Phil Liggett work?

PS: I don?t know, we just have a mutual understanding of when the other needs to say something. We have a similar background, we both come from the north of England and we have a similar sense of humour, which helps.

Which is your favourite Liggittism?

PS: Oh, there are so many. I think probably my favourite is: ?and now it?s Gerrie Knetteman breaking wind at the front?. That one made it into Colemanballs.

Are you optimistic about the future of pro cycling?

PS: Yes, I live in Africa and I live in a state of optimism about Africa, despite some of the grim events that are happening in Kenya right now. As long as we can stop bickering and sing off the same songsheet, cycling will be OK. When you go to places like California or Langkawi you see how the sport has become massively popular there in a short space of time and it?s a heartening development.

I know there is a problem with drugs, but do you think the three million people who went out and stood by the side of the road when the Tour de France came to London were wondering which rider was on EPO?

Don?t get me wrong, we have got to control doping because you can?t have people dying, but I sometimes think that cycling has been naive by being so open.

I think that cycling is right to be open and honest and confront the doping problem, but I don?t think it is right that cycling should be punished for being like that, and it has been. Other sports are a closed shop, and because of that it?s perceived that it?s cycling that has the problem.

At the end of the day, though, the sport is beautiful to watch and I think we should be positive about that. One reason why Phil and I are appreciated is that we?ve always taken that positive view.

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.