How they used to train: Eddy Merckx's chain gang

He might have been the greatest male road racer ever, but in the late 1960s and early 1970s Eddy Merckx also built one of the best teams ever. So how did he prepare them to race?

Illustration: Simon Scarsbrook

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

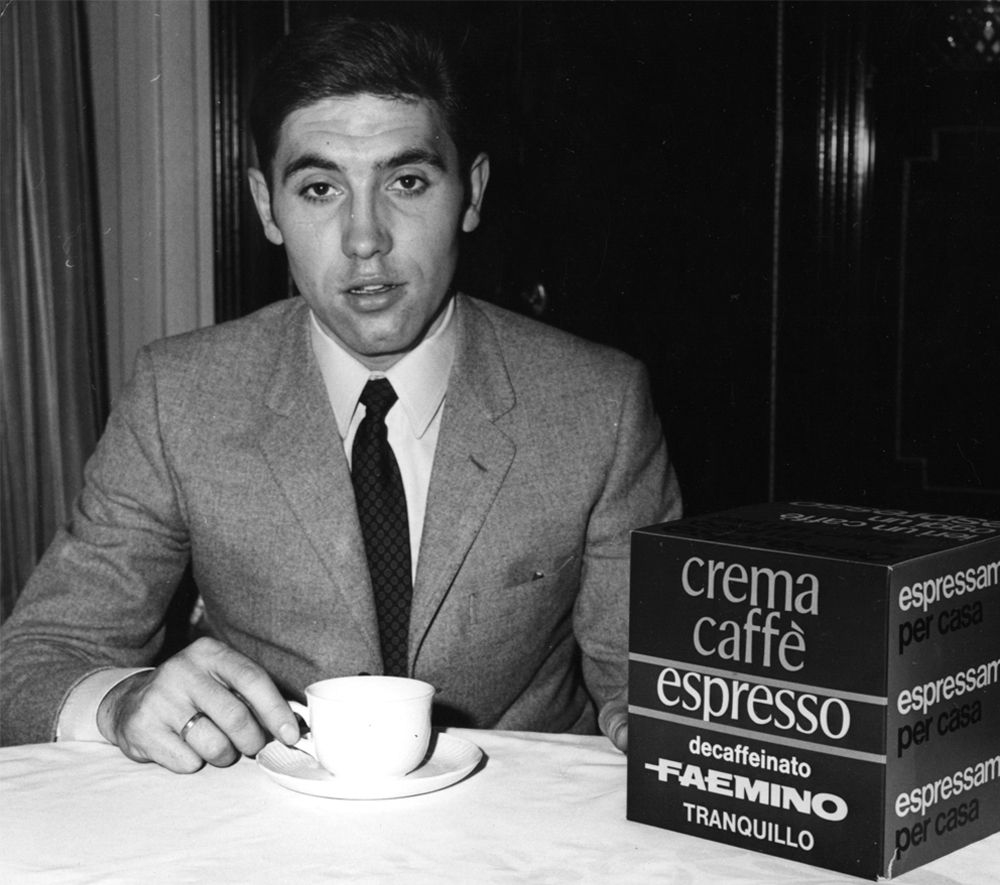

When Italian coffee machine manufacturer Faema recruited Eddy Merckx in 1968, part of the deal was to provide the cash not only to pay Merckx but to let him build the best team he could. That agreement was preserved when Molteni took over sponsoring Merckx’s team in 1971.

Merckx and his personal manager Jean Van Buggenhout enlisted the best talent possible, but with one proviso — anyone joining the team wasn’t just riding for anybody, but Eddy Merckx.

The pay was good, but you could forget personal glory. The deal appealed to some, but not everybody he approached, thankfully.

Once the team was assembled there was a pretty tough regime implemented. Training started with a bang on January 1 each year, and riders were expected to stay fit through to the end of the previous year. They had to cope with what Merckx had in store for them.

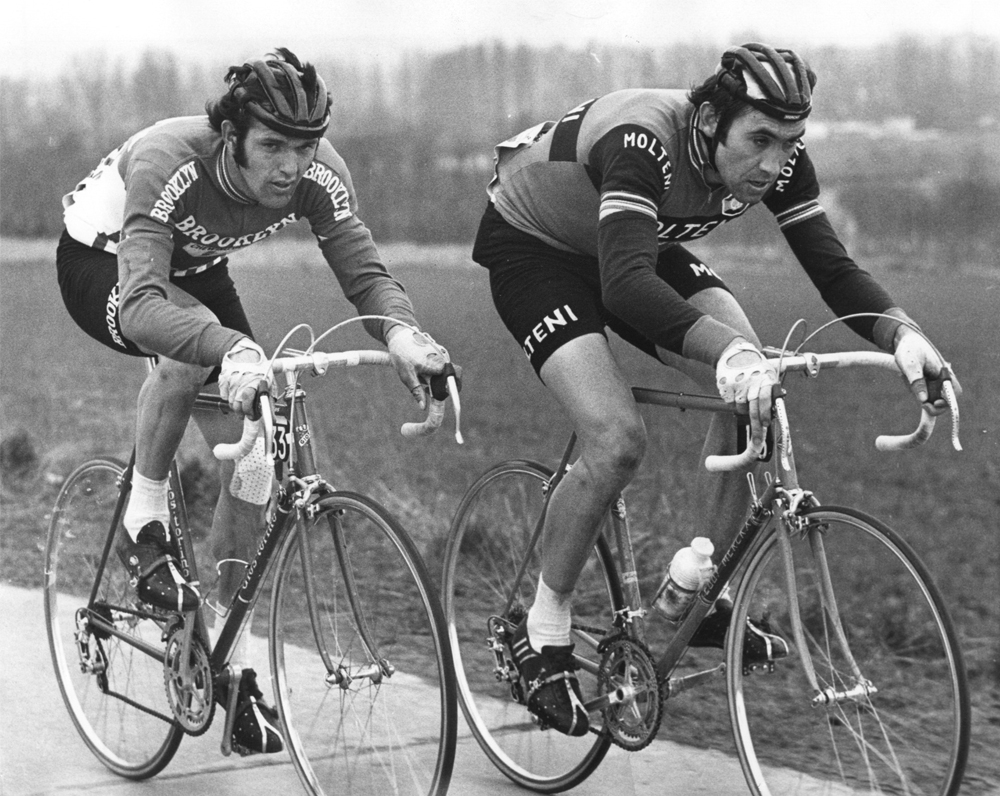

Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday the team met at his house just outside Brussels for a ride. Most of the team were Belgians, so they were expected to turn up. And the ride plan was simple and unwavering.

For almost the whole of January, the team rode 200 kilometres together. They rode side by side, swapping riders at the front. And they rode whatever the weather threw at them. Rain, hail or sleet, it didn’t matter.

They rode from Brussels to the East Flanders hills, the Flemish Ardennes, did a big loop of the Tour of Flanders climbs, then rode back to Brussels again.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“I used to see them,” said former British rider Barry Hoban. “I’d be out training, but the Flemish Ardennes are a lot nearer to where I lived in Ghent than they are to Brussels. I’d be on my way home and I’d shout, ‘Enjoy your 200 kilometres, lads,’ taking the mickey a bit, but the training worked.

“Merckx always had riders around him towards the end of a Classic. He always had team-mates who could set the pace and close gaps, setting things up ready for him to attack.”

The training group would have a team car following them, with bike spares, extra clothing, food and drinks because there were never any stops.

The car didn’t pick up stragglers though. Anybody who dropped behind had to make their own way back, then explain to the boss why they were late. And if it rained or if sleet fell, Merckx would just tell the group it would probably do the same in the Tour of Flanders, so they’d better get used to it.

Once back at Merckx’s place the riders showered and ate — usually the universal pro recovery food of Seventies Belgians, hot minestrone soup — then the group dispersed. And in the days they were at home, they were expected to do their own training.

It was a tough regime but when the season started in February, Merckx and his men were always ready. He was never less than competitive in his favourite first races; the Trofeo Laigueglia, Monaco GP and the Tour of Sardinia, often winning them.

Then Merckx would roar into the Classics. Winning Milan-San Remo seven times was no accident — it was based on those Monday, Wednesday and Friday sessions.

Illustration by Simon Scarsbrook

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast