'They opened up bicycle building for the normal person' - the frame building academy that changed an industry

It has been three years since The Bicycle Academy closed its doors, but its impact remains felt

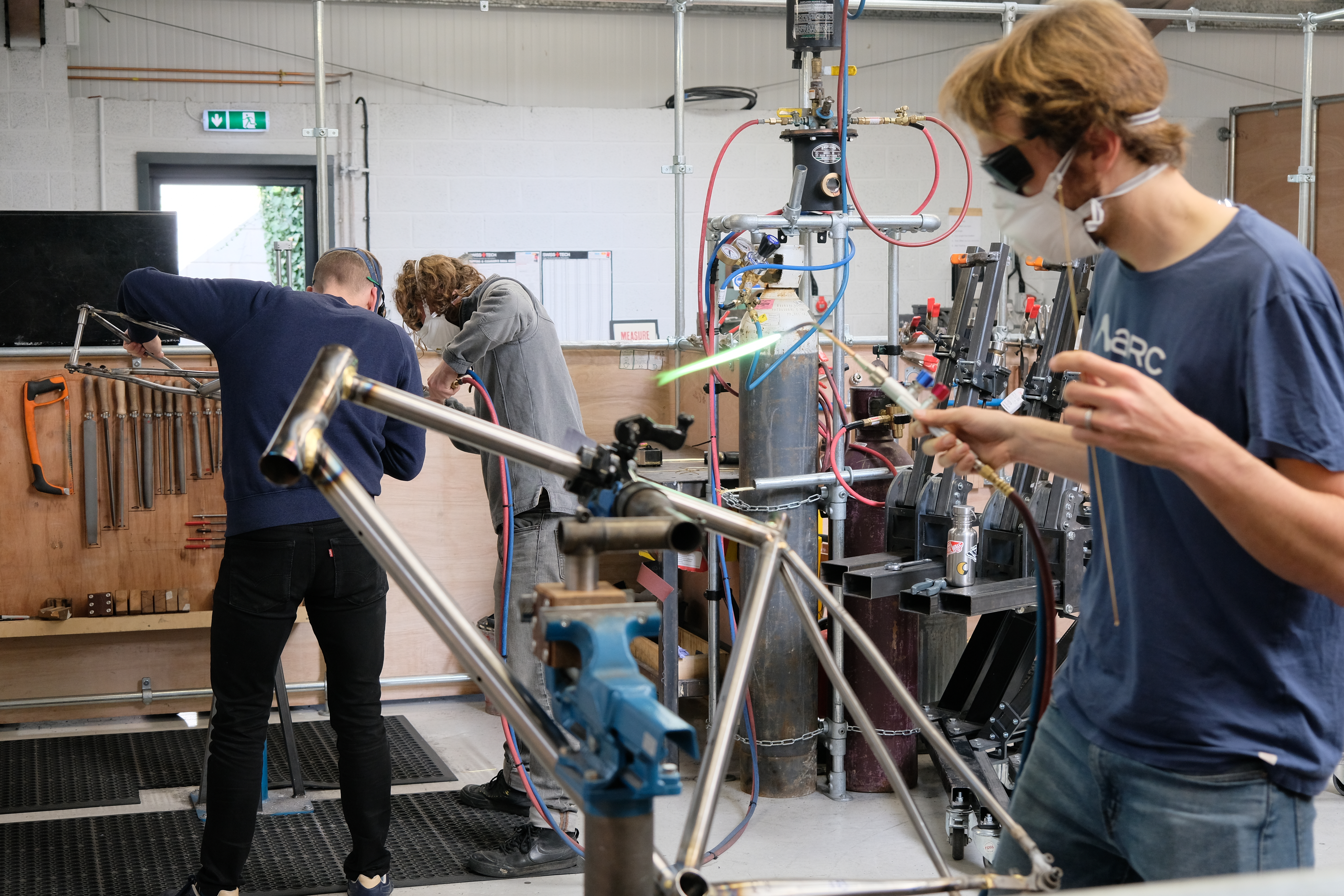

In 2011, The Bicycle Academy was set up, in southwest England, in an attempt to demystify the frame building trade. By 2022, it was forced to close its doors, due to the combined impact of Covid, Brexit and rising energy costs. But its proliferation of talented frame builders into the industry helped to breathe new life into the handmade scene in the UK and beyond. But what was its impact on the cycling industry? And what’s left now it’s gone?

I’ve always found it interesting how acutely you can grasp the measure of a person via voice alone. The Bicycle Academy founder, Andrew Denham is kind - I can hear it down the phone. He’s tired, too. Talking about the Bicycle Academy is a wound still fresh - “I put my entire thirties into it,” he says.

The Bicycle Academy was Denham's brain-child, grown from a one-man-plan into a team of dedicated mechanics working out of their Frome HQ by 2022. Denham had been shopping around for a frame building course – he didn’t want to make a touring bike, but he didn’t see much else on offer at the time. He was met, time and time again, with the same response: you can’t just build a bike from scratch - it takes time and practice and repetition.

Denham wasn’t satisfied with this response. Married to a teacher, with experience in education himself, he knew how transformative good teaching could be.

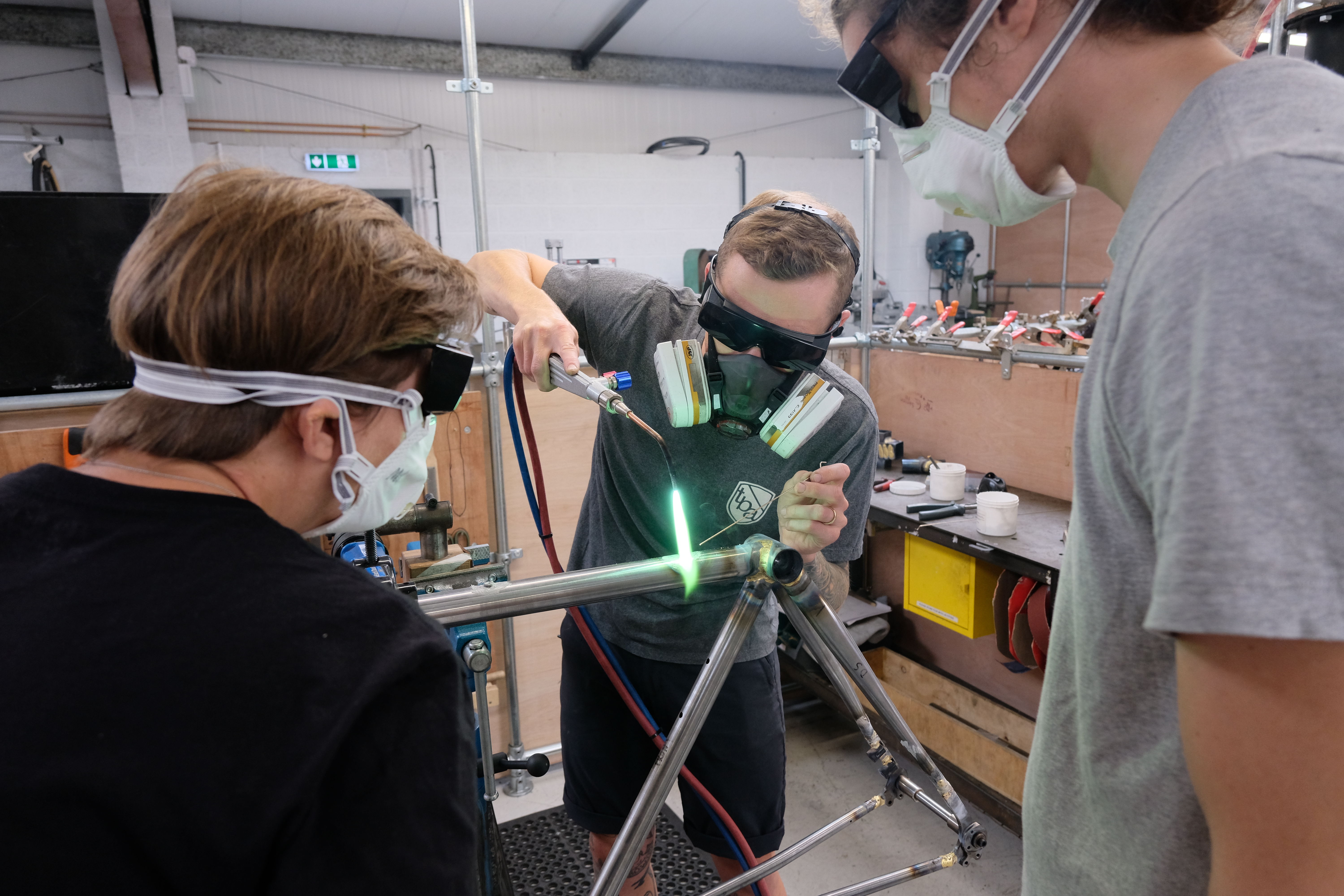

“Pretty much everybody has experienced wonderful teaching,” Denham tells me, “even if it's just one where a teacher really helps you to understand something, and it feels like they've completely unlocked it. And I knew with absolute certainty that the same could be achieved with frame building, because as I looked into it, so much of it was actually really basic - still complicated if you really want to go into the depth of structural design, but the truth was that most anglers didn't do any of that.”

And so, even before he’d made his first bike, Denham began teaching.

“It certainly felt much more of a choose-your-own-adventure type of outfit, rather than a do as I do setup under the tutelage of a single teacher,” Cyclingnews’ senior tech writer, Will Jones, remembers about his time at The Bicycle Academy. “You could find all sorts of machines going out of the doors. The courses were run in pairs, and as an example my training partner made a classic, disc-equipped road bike, whereas I went very old school and created a go-anywhere rough-stuffer with cantilever brakes and downtube shifters.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

By the time Jones trained with the Bicycle Academy, the team had honed their teaching style, but at the beginning, it was met with resistance. “It was a very difficult period because there was really meaningful pushback," Denham remembers. "I was being trolled by people that had been in position for a long time and felt undermined by the fact that we were doing a great job, and there were lots of new people doing great jobs.”

Denham had industry professionals wanting to check out what he was building in secret, and others who felt they shouldn’t have to pay. Denham knew that he was onto something - nothing bad has this amount of curiosity infused pushback.

The first bikes borne of The Bicycle Academy weren’t for the students to ride, however. They were sent to Namibia, to be donated to over one hundred teachers, nurses and school kids across the country. “It means that the person can learn by building something that they don't have the same emotional connection to, and therefore get stressed about, and the charity benefits enormously," he says. "So that was the idea, and then, I crowd funded to launch the business. And so for the first year you could only build a bike that you didn't get to keep.”

And soon people were coming from all over the country to experience what Denham was building. It wasn’t a cheap endeavour. A course would cost around £3,000, and for those coming from outside of the area, transport and local accommodation would push costs up even higher. “Approximately 40% wanted to just have a nice week and make a nice bike with nice people," Denham says. Others would turn up in sports cars, high powered experts in their relevant fields, there for a good time.

A photo posted by on

“I should say that it’s important to recognise it was during the period of time where craft was incredibly fashionable,” Denham smiles. “Spoon carving was the coolest thing, everyone started wearing leather aprons to make coffee.”

The other 20% of attendees, however, wanted to be professional. Amongst the academy's alumni are Rob Quirk, of Quirk Cycles, who has just received investment from Rapha-founder Simon Mottram to develop a line of boutique performance bikes, Jack Watney, a teacher on the course now with Sturdy Cycles and a partnership with Brompton, that saw equipment designed by TBA used on their T line. Sam Farrar started making frames from his garage at home after completing the course: “I called my frames Manuka, after the honey, that's sweet, and medicinal - just like riding a bike.” He’s made twelve so far, for his friends and family. “I love to see them out in the wild,” he said, “and hear about the journeys they go on.”

The thing Denham is most proud of, out of those years and years working with people to build frames, is the teaching.

“There was one person who came onto the course, and he absolutely cried his eyes out on the ninth day,” Denham remembers. “It transpired that when he was a kid, one of his teachers had said some stuff to him about not being able to do something, and it just got stuck in his head. He was in his 40s at this point, and it was at that moment where he finished the frame and he was holding it, that he just completely broke down. He said that this teacher had basically undermined his sense of confidence in himself and his ability to physically make things.

"Actually, he did a wonderful job. He was very nervous and quite anxious because of all of this stuff, but it was the most wonderful thing, and I'm deeply proud of that, that he was able to experience… almost the repair of his own sense of self.”

Jones remembers being taught by Watney, now of Sturdy Cycles, who was “patient, kind and probably most importantly had a ‘learn by doing’ attitude that made me feel like I could have a go at anything.” Sam Farrar started a two week course, and - in a turn of events unbelievable to him - completed it.

“The whole experience was very eye opening for me as someone who was usually always thrown out of class as school, and had a pretty terrible track record with most teachers, to walk into a classroom and have total engagement for 7 days,” Farrar told Cycling Weekly. “It did make me wonder what my school days would have been like if education was like this always.”

Trawling through the long list of alumni Denham sent me after our chat, a quick Google returned many broken website links: “We’ll be back soon!” an eerie reminder of an industry struggling against the combined costs of COVID, Brexit and rising energy costs - this, ultimately, is what spelled the end of Bicycle Academy, too.

But of the websites still live and online, the ethos Denham ran The Bicycle Academy with runs at their heart. “Welcome to NoMad cycles,” reads one introduction, “I pride myself on dedicating my time and efforts into every bike irrespective of its cost, a bike is what you use to explore and a bike is just as precious as a car.” Adeline O'Moreau of Mercredi Bikes started building bikes designed with the simple ethos: "No nonsense, made to measure, bicycles for all."

“Go to any handmade bike show and you’ll find Bicycle Academy graduates," Jones said. "Some of these endeavours were short lived, but I’m certain that it generally played a part in not only keeping the handmade scene alive in the UK, but also keeping it fresh."

Cycling Weekly’s tech editor, Andy Carr, is more emphatic: "To a wonderful extent they opened up bicycle building for the normal person. It was an overly protected, dark art, that was shrouded in secrecy before TBA turned up. UK frame building isn’t what it was without TBA at the centre of it, in my view.”

A year after the Bicycle Academy closed its doors, frame building entered the red list for endangered heritage crafts. Petor Georgallou, co-owner of the hand made bicycle show Bespoked and alumni of the academy, said that its loss couldn't be underestimated. The ability to not just buy a bike that has been made by hand in the UK, but to be part of that manufacturing process, is dwindling. But there will always be people ready to pick up a some carbon and set to work - just how this will impact the wider cycling industry as opportunities for everyday riders to hone their craft becomes ever more throttled, remains to be seen.

Andrew Denham continues to produce bicycle parts under the banner of Academy Tools, and hosts the yearly hill climb in Froome, 'The Cobble Wobble.'

A photo posted by on

Meg is a news writer for Cycling Weekly. In her time around cycling, Meg is a podcast producer and lover of anything that gets her outside, and moving.

From the Welsh-English borderlands, Meg's first taste of cycling was downhill - she's now learning to love the up, and swapping her full-sus for gravel (for the most part!).

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.