Why does cycling clothing look so torn up after a crash?

How delicate is the material and how hard are the crashes?

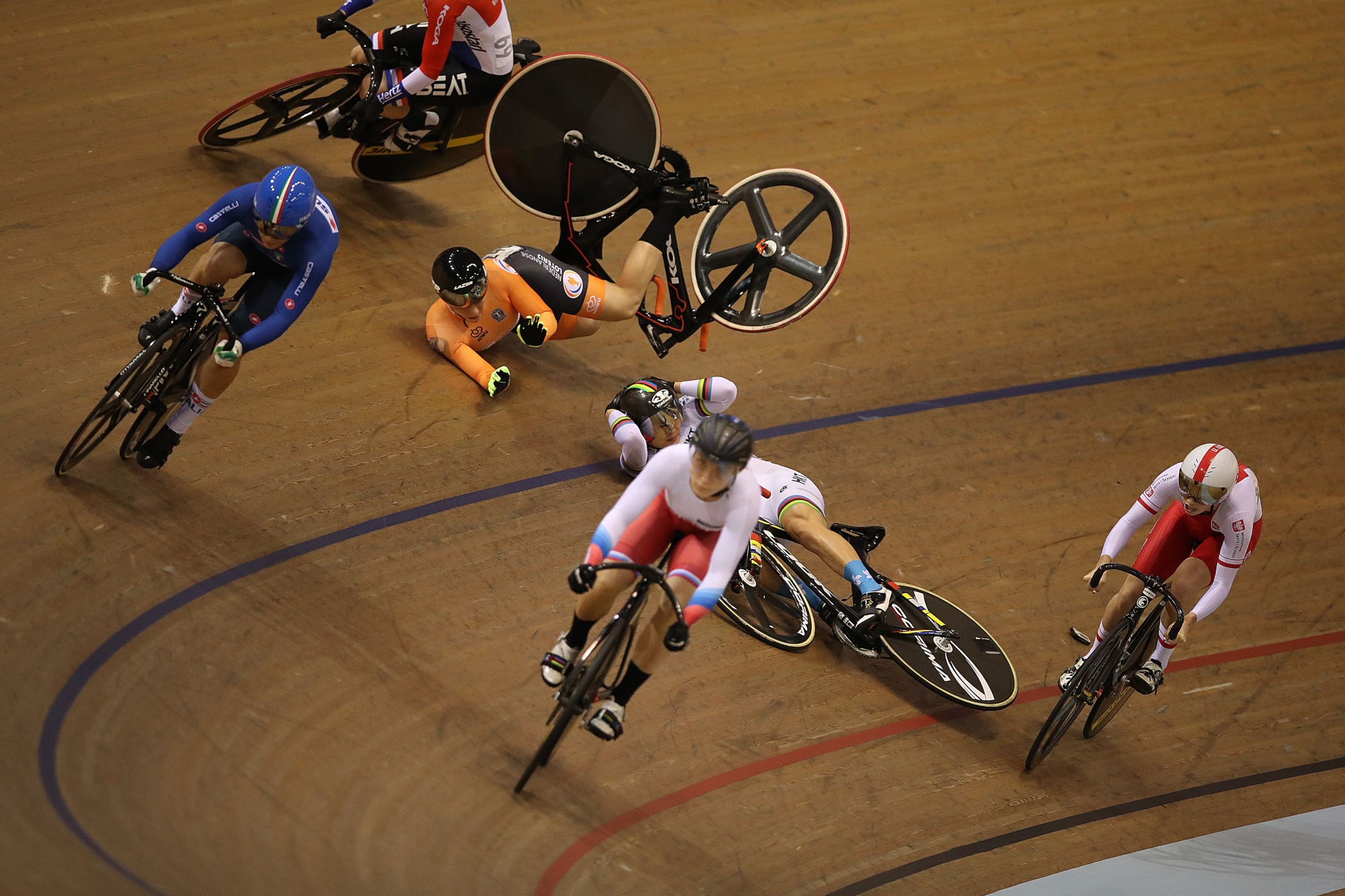

Crashes are an unfortunate, but inescapable, part of professional cycling. That said, the opening stages of the Tour de France have sadly seen far more riders hit the deck than we ever could have expected.

Mercifully, many of the riders who have crashed have still been in a position to get back on their bikes and back into the peloton. As a result, we’re seeing many more images of riders with clothes limply hanging from their bodies than we ever usually do.

Now, no one’s ever going to be looking their smartest after hitting the ground – and participants in other two-wheeled sports, such as mountain biking and MotoGP, are able to wear much more protective clothing.

But even compared to cross-country mountain biking – where the physical exertion and clothing demands are broadly similar – the kit of WorldTour riders does seem to be left in a particularly bad way after a crash.

We’ll take you through the reasons why – there’s much more to it than just a roadie’s obsession for featherweight kit.

The surfaces

It’s natural to expect off-road crashes to be the more serious: there’s a whole range of unfortunate things you could end up landing on – rocks, roots, vicious brambles. The road, in contrast, is quite open and with a consistent surface, so you’re less likely to be unlucky than you are off-road.

But while the road may be a known quantity, and the surface is quite uniform, tarmac itself can actually be quite rough and much more akin to sandpaper than anything else. Although it may feel smooth when riding or driving over it, when sliding along it can just tear your clothes – and skin – to shreds.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Although there is the possibility of landing on something quite unfortunate when riding off-road, when you’re just landing on dirt there aren’t the same abrasive qualities and therefore there’s much less of a tendency for clothes to get torn up.

On rockier surfaces – particularly ones with smaller stones – there is more potential for clothing to be ripped through. But to continue the analogy with sandpaper, as the road is much 'finer', there’s much more scope for sliding along it and therefore having greater contact. Crash off-road and you’re more likely to come to a stop sooner, with the result being that your clothes, at least, stay in a better shape. Any damage from the impact, such as a broken collarbone would be much the same.

The speeds

Road cyclists tend to travel much faster than mountain bikers. The peloton can be ticking along at 50kph on the flat – and it doesn’t take much of a downhill, or acceleration before a pinch point, to send the speeds shooting above 60 or 70kph.

In mountain biking, just breaking 50kph is generally considered fast – and those speeds tend to just be reserved for more open parts of the course where crashes are quite unlikely. The more technical and riskier parts of the courses – where crashes are most likely to happen – are generally a fair bit slower than that.

The old quip “it’s not the fall that hurts you, it’s the sudden stop” rings equally true here. With road cyclists moving so much faster than mountain bikers, they need to keep travelling for longer – or else they would end up with much more serious injuries from a faster deceleration. But as a consequence of this, roadies’ clothing does stand to end up much more tattered.

No concessions

But even with the speeds and the surfaces, such torn clothing doesn’t have to be the result. Of course, it wouldn’t be practical for the peloton to all don motorcycle leathers, but there are some fabrics which do offer improved crash resistance while also being lightweight and breathable enough to cycle in.

Of those, Dyneema is perhaps the best known, being used worn by Tom Dumoulin (Jumbo-Visma) of the then Giant-Alpecin team (now Team DSM) during the 2016 Tour de France. More recently, in December 2020, Team DSM launched a new clothing brand, Keep Challenging, in partnership with longtime clothing manufacturer BioRacer. One of the main focuses was to integrate Dyneema fabrics to improve abrasion resistance.

But this technology still remains a little on the fringes within the pro peloton. With team optimising everything for ultimate speed and performance – from the equipment to the riders themselves – integrating abrasion resistance is something that is often left by the wayside.

After winning the 2019 National Single-Speed Cross-Country Mountain Biking Championships and claiming the plushie unicorn (true story), Stefan swapped the flat-bars for drop-bars and has never looked back.

Since then, he’s earnt his 2ⁿᵈ cat racing licence in his first season racing as a third, completed the South Downs Double in under 20 hours and Everested in under 12.

But his favourite rides are multiday bikepacking trips, with all the huge amount of cycling tech and long days spent exploring new roads and trails - as well as histories and cultures. Most recently, he’s spent two weeks riding from Budapest into the mountains of Slovakia.

Height: 177cm

Weight: 67–69kg