I tried eating like a Tour de France rider for a day - here’s how I coped with the huge calorie intake

The mountains of food Tour de France riders have to chomp through are nearly as daunting as the cols themselves. I tried to find out what is it actually like to eat for a Tour de France stage

A 70kg rider pedalling hard burns approximately 1,000kcal per hour. Riders in this year’s Tour de France will cover 3,405km, and if we assume an average speed of 40kph, that’s 85 hours of riding – burning in the region of 83,000kcal, or 4,000kcal per stage. That’s a very rough estimate, of course, and doesn’t take into account the ‘tickover’ energy needed to keep the body functioning 24/seven, but it hammers home the magnitude of the eating challenge: 83,000kcal is the equivalent of 64kg of pasta or 44 loaves of bread – literally gut-busting quantities of food that the pros have to eat to compete in the Tour de France. I wanted to find out how they do it and just how difficult it is to keep up with the vast energy demands of the race. So I decided to find out – by fuelling like a pro for a day.

Rather than sitting on the couch ordering takeaways all day, I would mimic a Tour de France competitor’s fuelling while riding the equivalent of a demanding stage. I had neither the time nor budget to do this experiment in France on an actual route from the race (sob!), so I needed to choose a stage I could replicate on the Northern English parcours on my doorstep. Stage 10 from the 2022 edition of the Tour de France, from Morzine to Megève looked ideal: a relentlessly hilly 148km.

I would start in my home town of Otley in Yorkshire, head out through Ikley, then up into Skipton before taking on the steep slopes of Malham; turning for home, I’d make my way up over Greenhow and across the moors to finish. This would mean covering 143km, just 5km short of Stage 10’s distance. Admittedly, no Yorkshire climb was going to replicate Stage 10’s finale (1,384m) but adding together all my smaller ascents, I would accrue just as much overall elevation, a total of 8,225ft (2,507m).

Carb load

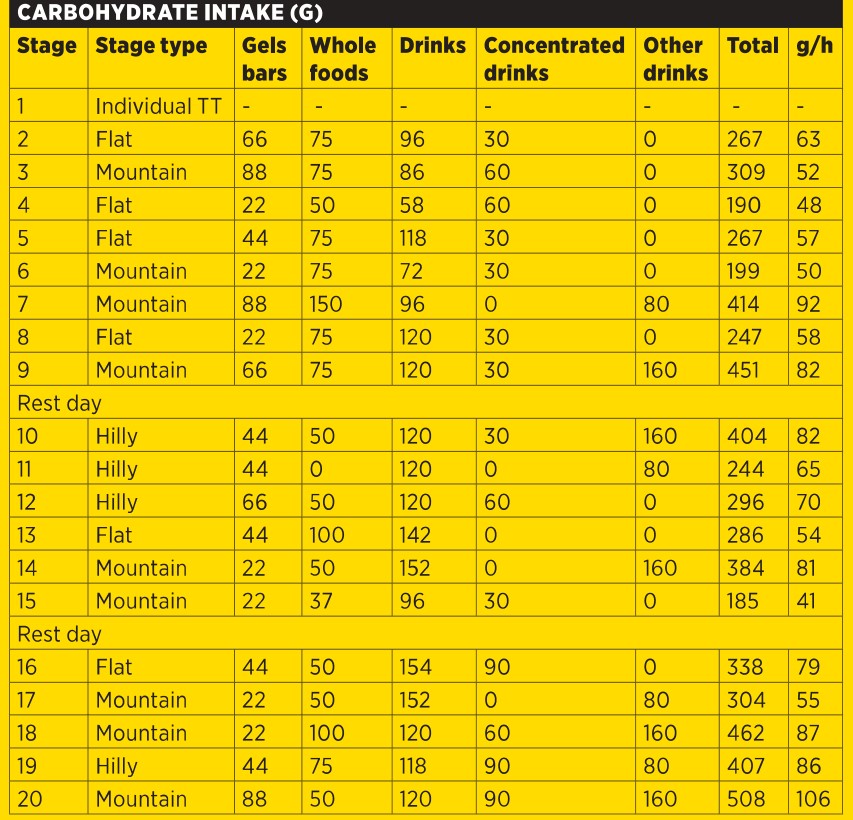

Sport Performance & Science Reports published a paper entitled ‘Case Study: The application of daily carbohydrate periodisation throughout a cycling Grand Tour’ – showing exactly how much carbohydrate a pro rider in the 2021 Vuelta a España consumed on each stage, casting a light on the vast energy requirements of a Grand Tour.

The study’s subject, an unnamed 26-year-old rider, consumes a staggering 843g of carbohydrates a day on average, peaking at 1,100g on the most demanding day – equivalent to 4kg of cooked rice. I’d need to consume between eight and 12g of carbs per kilo of bodyweight; in other words, I was going to have to stuff my face like never before.

Why are such huge helpings of starchy foods vital for a stage racer? “Carbohydrates are king for endurance,” advised Will Girling, team nutritionist for EF Education-EasyPost. “They are the primary energy source when cycling at anything above a moderate effort. Ensuring riders have a high carb intake throughout the race not only aids performance but has been shown to improve recovery after cycling too.” While carb requirements vary day to day depending on the length and profile of the stage, protein remains consistent. “Protein intake doesn’t fluctuate, it is always at a minimum of two grams per kilo of body weight,” added Girling. As for fat: “We try to stay at the lower end, but it’s usually between one and two grams per kilo of bodyweight a day.”

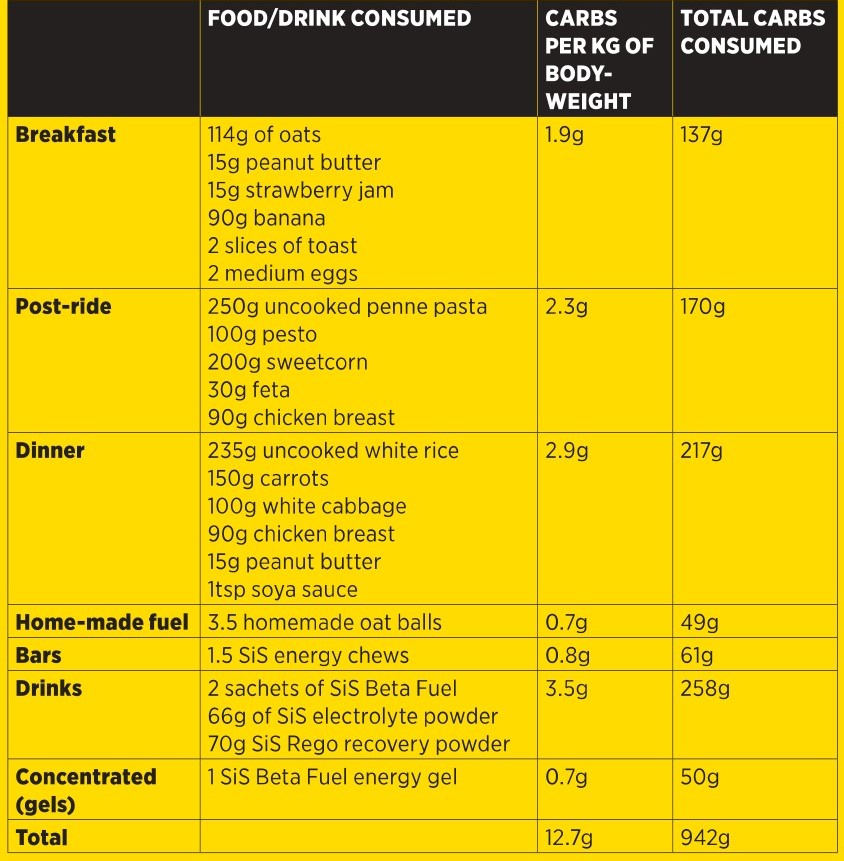

On the morning of my ride, I weighed in at 74.1kg, and decided to aim for the upper end of the intake guidelines, 12.7g of carbs per kilo, meaning I’d need to eat a total of 943g – nearly a full kilo of pure carbs. My next job was to break this down into breakfast, on-bike and post-ride fuelling. What shocked me most was just how much carbohydrate I would need to consume in liquid form.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Tallying up the intake

“Trying to hit 90-100g of carbs per hour can be very difficult on solid food,” explained Girling. “The bulky nature of it, and the process of chewing, increases the feeling of fullness. You just can’t get that amount of solid food down on the bike.” This is even more difficult if the racing is aggressive and the effort level high.

To make my challenge as realistic as possible, I would ride as hard as possible while consuming two sachets of Science in Sport (SiS) Beta Fuel 80 (160g of carbs) on the bike.

I started the day with porridge, my usual race day breakfast, keeping in mind Girling’s caution that “it’s important to not feel really full or stuffed” before you start riding. The best way to side-step the overfilling problem, he advised, was to add extra carbs in the form of sugary toppings such as maple syrup or honey. I decided to stick to what I knew and added a dollop of peanut butter and strawberry jam to my porridge.

To help me keep an accurate tally of my cycling nutrition, I used the MyFitnessPal app, and weighed out all my portions. Here’s the breakdown of what I ate across the day:

My porridge amounted to 78g of carbohydrates, so I still needed an extra 60g. Scrambled eggs on two slices of toast, followed by a large banana, and finally I was there: 134g of carbs were in my belly. Feeling slightly uncomfortably full, I gave myself two hours to let everything digest.

Fuelling on the stage

0 - 50km: Otley to Skipton

Imagining myself in the peloton and settling into the race, I pushed on at a tempo of around 300 watts over the opening 25km of rolling hills, eating three homemade oat balls (see recipe below) 20 minutes apart. Over the first hour, I consumed 60g of carbs in total, 30g from liquid, 30g from solid food. To stay hydrated, I aimed to consume 500ml of water per hour.

After 40km I’d already climbed about 1,000ft, and now pushed on up over the first proper climb of the day to the top of the Cringles. In my imaginary Stage 10, this is where the break was likely to go, so I tightened up my shoes and put the power down. The intensity was too high to eat solid fuel now, so over the next hour I drank a bottle of Beta Fuel containing 80g of carbs.

51 - 100km: Skipton to Grassington

Malham Cove loomed in the distance: a climb of 2.6km at an average gradient of 7% – arguably the toughest part of the ride. Still trying to distance the imaginary peloton, I kept the power high and stuck to the nutrition plan, eating one and a half SiS Beta Fuel chews (46g of carbs per chew), washed down with water. Mixing up the textures and flavours definitely helped keep my appetite interested.

The grind up and over Malham out of the way, I headed into the Dales, and was finally riding with the wind, a welcome relief after 2.5 hours of headwind. But now I was heading into unknown territory in terms of my endurance. Though I’m used to long rides of over 3.5 hours, I usually do them at low intensity - training zone wise that’d be Zone 2 - whereas now I was pushing hard. This is where fuelling would make all the difference, and so far I’d stuck to the plan: 90g the first hour, 80g in the second and 70g in the third hour.

In the fourth hour, I drank another bottle of SiS electrolyte mix, ate half a homemade bar and one Beta Fuel energy gel. I wasn’t feeling hungry at all and was grateful that I only had a few bites of solid food left. The temperature had climbed to 17ºC – tropical for Yorkshire – so drinking the liquid carbs wasn’t a problem.

101-143km: Grassington to Otley

After a long, gradual drag up onto the moors, Greenhow hove into view, and my stage win fantasy was entering its critical phase. On the downhill before the final ascent of the day, I popped another gel, grabbed my final bottle of Beta Fuel and raced into the final 40 minutes. This would be the real test, the point where the stage is won or lost.

I was pleasantly surprised, my legs still felt relatively fresh given the four-and-a-quarter hours of hard effort, and I was able to get out of the saddle and dance on the pedals as I unleashed everything towards the finish line. Done. I’d ridden 143km, climbed 8,225ft, and more importantly I’d consumed 399g of carbs. It had taken 4.5 hours and I’d burnt almost exactly 5,000kcal while averaging 284W (309W normalised) for an average speed of 31.5kph (19.6mph).

Homemade on-the-bike snack recipe

My favoured on-bike fuel for my ride were these homemade oat balls, taken from Volume 2 of The Cycling Chef by Alan Murchison. They are named ‘Cheryl’s coconut oat balls’ because the recipe was ‘borrowed’ from a British Cycling soigneur. I loved the subtle flavour, and they were really easy to eat on the bike.

INGREDIENTS

- 200g oats

- 150g dates

- 100g honey

- 100g peanut butter (or any nut butter of your choice)

- 15g chia seeds

- 15g desiccated coconut

- 2g salt

METHOD

1) Add oats and dates to a blender and blend into a paste.

2) Add the other ingredients and beat it all together.

3) Roll the mixture into 40g balls (making approx 14).

4) Store in an airtight container in the fridge.

Looking for more on-bike nutrition snacks? Here’s how to make Superseed Flapjacks and Veggie Rice Balls - and you can find even more homemade energy bar recipes over here.

Post-stage refuelling

In a real Grand Tour, my ride would have been just one of 21 stages, and crucial now, having finished, would be the replenishment of my glycogen stores, as well as taking on enough protein for muscle repair. Following the recommendations, I now needed to eat a further 208g of carbohydrates. “Riders have a recovery drink and quick-release carbohydrates,” Girling said. “The form varies day to day; some riders like sweets like Haribo, others prefer a sugary drink.” I opted for a bottle of chocolate-flavour SiS Rego recovery drink, which gave me 24g of protein and 38g of carbs, before then refuelling with real food.

For my post-ride meal, to be eaten as soon as I’d showered and changed, I opted for 250g (raw weight) of pasta with some pesto, chicken and sweetcorn. This was arguably the biggest challenge of the day, as I just wasn’t feeling hungry. After much slow chewing and resentful staring at my fork, the bottom of the bowl eventually came into sight.

Food fatigue and repetition can be a real problem for riders, and I began to understand why. Eating was the last thing on my mind as dinnertime approached. For my biggest meal of the day, I was expected to eat a whopping 217g of carbs – almost three grams per kilo of body weight. How do pro riders manage it? “We rotate themes,” Girling told me. “Mexican food one night, Japanese the next, then perhaps local cuisine from the area – whatever it takes to keep it interesting and appetising.” Heeding Girling’s final tip, “learn to love rice”, I cooked myself a chicken stir-fry.

Behind the scenes

It’s the challenge you don’t see taking place behind the scenes of the Tour: nutritionists and chefs making sure their riders are getting enough carbs and calories. Across the single day of my challenge, I consumed a total of 942g of carbs and 5,726kcal, which still left me with a deficit of 1,800kcal. If I did that over a few days, the diminishing energy reserves would soon take their toll.

Aside from energy requirements, how do the pros make sure they’re getting all the vitamins and minerals they need? “Most take a multivitamin, which covers all bases, an omega-3 supplement to help with recovery, a probiotic to boost immunity and gut function, as well as whey protein, and tart cherry juice to help with inflammation.” All of these are worth considering to “help support overall health,” Girling suggested.

It’s been an eye-opening experience as an amateur rider to eat like a WorldTour pro for a day. My usual training volume is around 15 hours a week, and I rarely consume more than 20g of carbohydrates per hour on the bike. Reflecting on how strong I felt on my Stage 10 simulation ride, while consuming vastly more carbs, has taught me a lesson. I’ve realised that there are times – such as in the fourth hour of an endurance ride or in the final set of intervals – when I could benefit from taking on more fuel. It’s not every day I’ll need to consume 5,500kcal, of course, but I’ll certainly be thinking more carefully about the amount of nutrition my rides and races really demand.

This full version of this article was published in the print edition of Cycling Weekly. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered direct to your door every week.

Tom Couzens is a racing cyclist currently representing The Ribble Collective on the road and the Montezumas cyclo-cross team off road. His most notable results include winning the Monmouth GP national series race as a junior; finishing sixth in the 2022 British National Cyclo-cross Championships; and he was selected to represent Great Britain at the European Cyclo-cross Championships in 2020/21. Tom draws on his high-level racing experience and knowledge to help Cycling Weekly readers maximise their potential and get as much as possible out of their riding.