Major Taylor’s London excursion

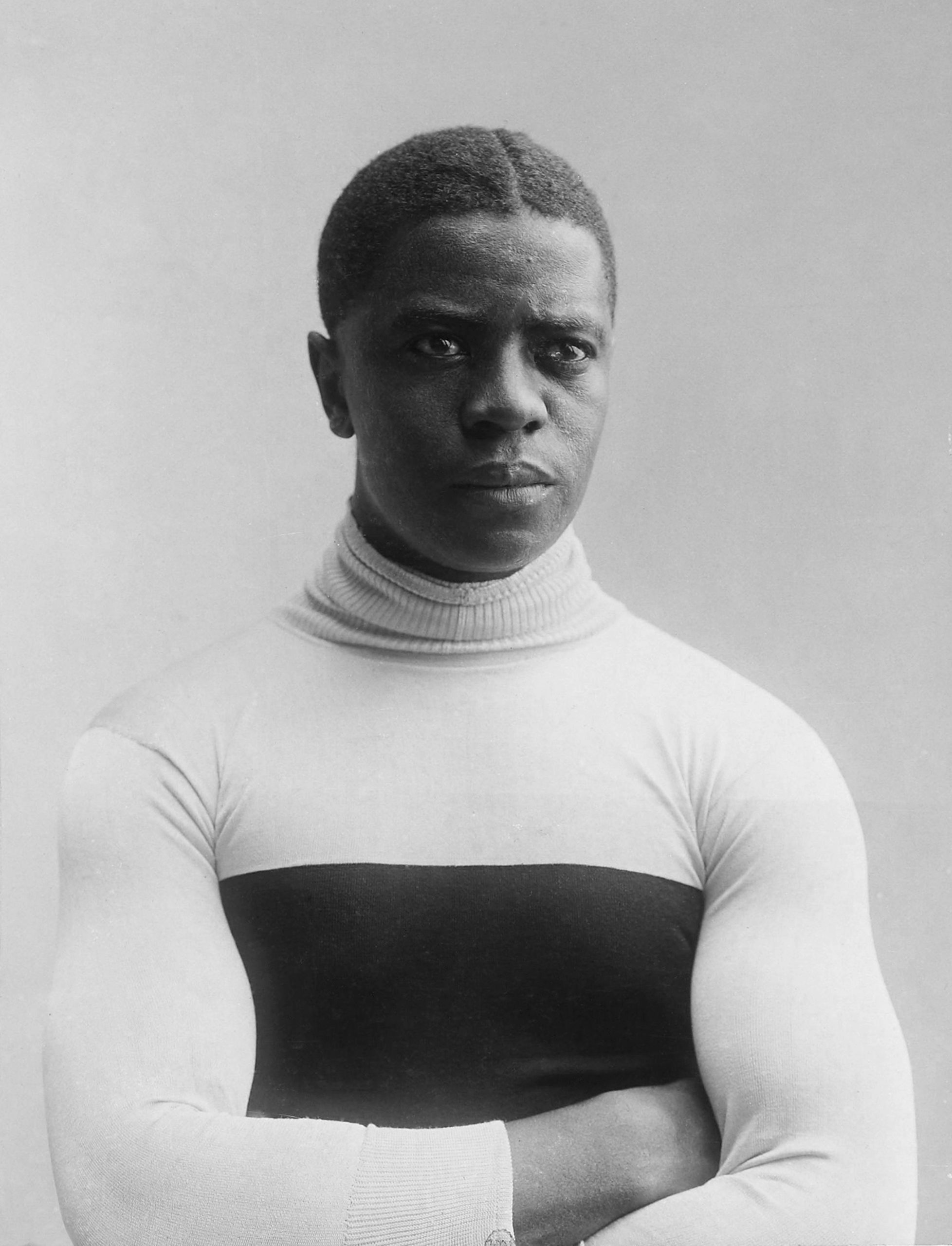

In the early 1900s there was no bigger cycling star than Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor. Cycling’s first black world champion, Taylor achieved success in the face of much discrimination, touring Europe, Australia and North America and winning in the world’s most famous velodromes, writes Giles Belbin

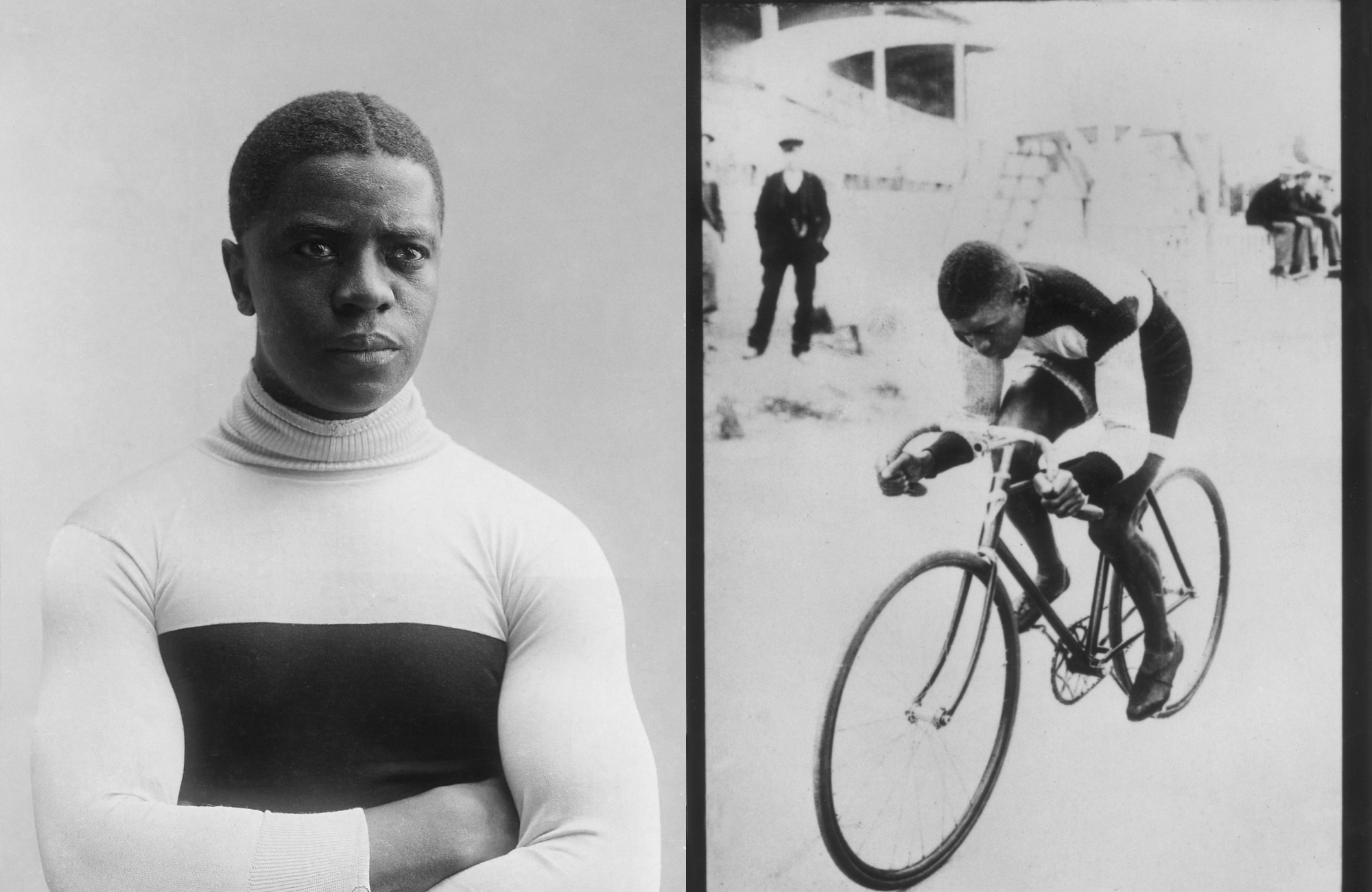

Major Taylor (Getty)

It is early August, 1903. The cycling correspondent for Sporting Life is making his way to the Three Nuns Hotel in Aldgate, notebook and pen safely stowed, pleased to have received an invitation to lunch with “a crowd of cycling celebrities”.

On entering the hotel our correspondent finds his hosts and settles down to enjoy a lunch of steak and fried potatoes, “washed down with good old English bitter”. At the table is Victor Breyer, the manager of the Buffalo velodrome in Paris. Breyer is in town for a race meeting at the Memorial Grounds, Canning Town, and has brought with him a couple of French stars – the sprinter Charles Piard and ‘the paced wonder’ Henri Contenet – alongside the American sprinting sensation, Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor.

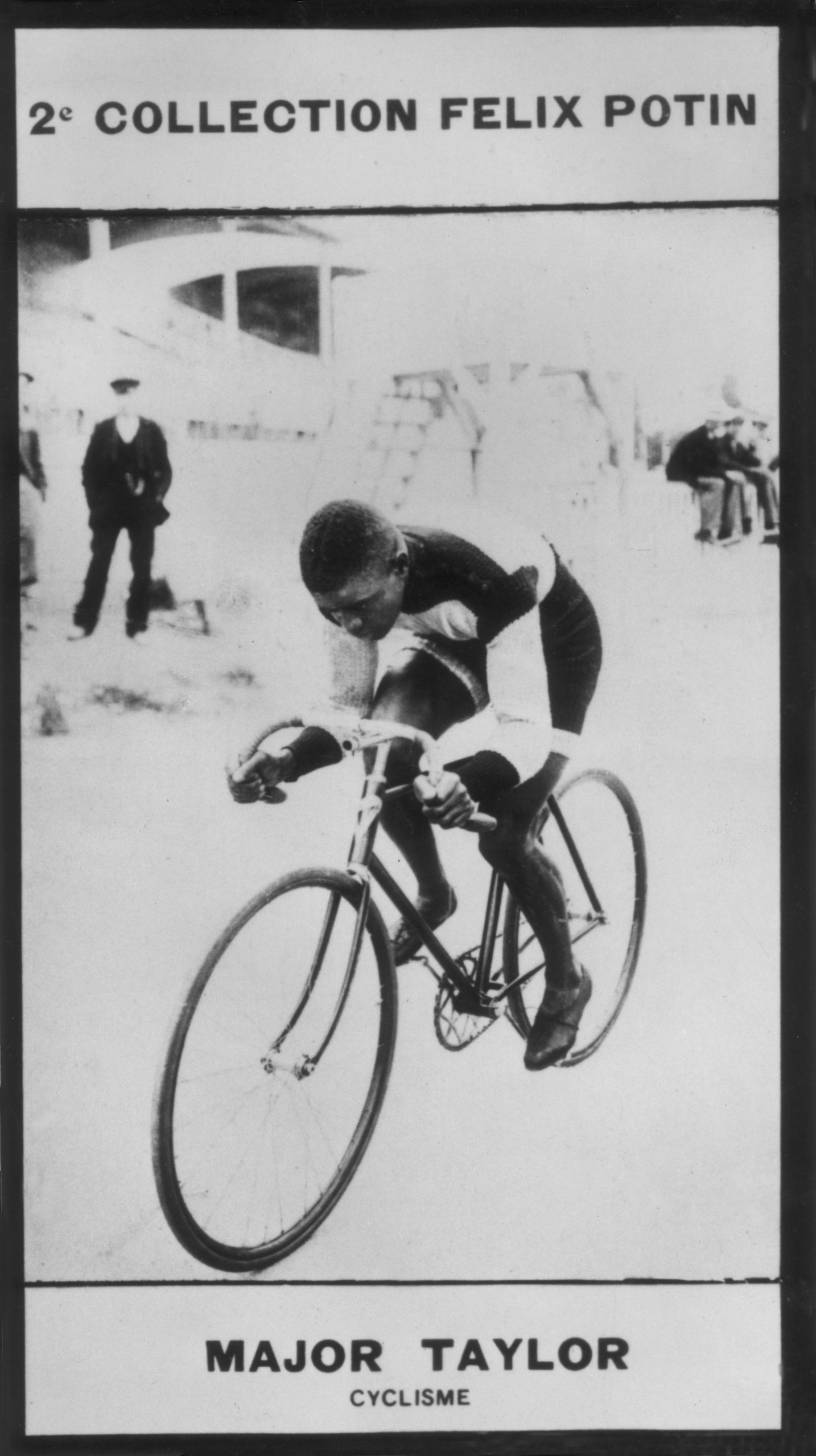

The Memorial Grounds has never before hosted such a prestigious event. Billed as the nation’s “cycling event of the year”, on the card is an attempt by Contenet on the 10-mile record and a three-race sprinting contest, each contested over one mile, between Taylor, Piard and Sid Jenkins, a Welsh rider who is considered by Cycling magazine as Britain’s best professional. Piard and Jenkins are well-known, but it is Taylor, a 24-year-old African American, who is the real draw.

During lunch Sporting Life’s correspondent scribbles away as the deeply religious Taylor, drinking only milk and water, shares his thoughts on racing and training. “Bed at 10 o’clock and up at 7:00 all year round… plenty of boxing, skipping and other indoor exercise, with a little running and practice twice daily on the machine [bicycle] is a standard programme which Taylor carries out when head-quartered at any particular track,” the correspondent will later report.

The next day some 10,000 spectators crowd into the Memorial Grounds and see Taylor dominate proceedings. He rides impressively and wins all three contests and demonstrates great versatility, employing a range of tactics, from headlong early sprints to slow manoeuvring up and down the banking.

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

“He has little to learn in the art of finessing and possesses a sprint which landed him a winner on the tape every time,” reports Cycling a few days later. “Taylor watched his men like a cat does a mouse.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Not that the finer details of sprint racing are universally appreciated. “The Canning Townites failed to appreciate the ‘head-work’ tactics of the three riders,” observes the same report. Two weeks later, the Sportsman will run a piece on Taylor’s display that opines: “In England the object of the ‘loafing’ [crawling and feinting] is as well understood as in Paris but is not equally pleasing to the phlegmatic Britisher. It

is a question of national temperament.”

For Jenkins, however, Taylor’s talent is self-evident. “I’ve been beaten by the fastest rider in the world,” he says afterwards. “That’s the only excuse I have to offer.”

Taylor quickly returns to Paris with Breyer but not before saying for the benefit of the British press that the Canning Town track is the finest in Europe. Whether he truly believed that or not, Taylor’s August 1903 appearance in east London will prove to be the one and only racing appearance in Britain of perhaps the greatest track cycling star of the era; an all-too brief glimpse of a remarkable racer and a man who achieved great success in the face of extraordinary prejudice.

The rise of the Major

“I first found a copy of Major’s autobiography in a bookshop in Oakland, California, in about 1975,” says Andrew Ritchie, author of Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer. “I started looking around to see what else I could find on him and was pretty amazed to find there really was nothing apart from a few sketchy articles here and there. I collected what I could, read his autobiography, and kept thinking that this was a pretty amazing story.”

Marshall Taylor was born in 1878 in Indianapolis. One of eight children, Taylor’s father worked as a stableman for the wealthy and white Southard family. The Southards had a son, Daniel, who was the same age. “We soon became the best of friends,” Taylor later wrote in his autobiography The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World, “so much so in fact that I was eventually employed as his playmate and companion… I was the happiest boy in the world.”

The young Marshall was embraced by the Southards. The family gave him a bicycle so that he could join Daniel on rides and they played happily with Daniel’s other friends, all of whom were white. One day the group of boys went to the YMCA gymnasium where Taylor was barred from entering. His friends protested but to no avail. “I could only watch the other boys from the gallery,” Taylor wrote of the day that introduced him “to that dreadful monster prejudice, which became my bitterest foe.”

Taylor grew into a talented cyclist. He worked for a bicycle store in Indianapolis, performing tricks outside while dressed in a military uniform to drum up business and earning the moniker Major. The shop promoted an annual 10-mile handicap race and the owner encouraged Taylor to start. He was still little more than a child and didn’t want to race against adults. Taylor had tears in his eyes at the start, prompting the owner to whisper he only had to start to drum up interest and not to worry about finishing. As it turned out, Taylor not only finished but won the race. “Master Major Taylor, of this city is without doubt the expert wheelman of his age in the state,” reported local paper the Freeman. “[He] won in 56 minutes and 15 seconds, receiving a handsome gold badge.” Taylor writes in his autobiography that he was 13 at the time but the newspaper report is dated July 1890, meaning he could only have been 11 years old.

Fast-forward six years and Taylor was racing professionally, having been brought under the wing of a former pro rider Louis ‘Birdie’ Munger. “Munger recognised that Taylor had talent and ability,” says Ritchie. “He realised he had a real champion on his hands.” Taylor won his first professional race, a half-mile handicap race at Madison Square Garden in 1896, claiming $200 in prize money that he sent straight home to his mother. Three years later he won the sprint event at the ICA World Championships in Montreal, sealing his status as the fastest rider in the world.

To Europe and beyond

Despite his status as a genuine sporting superstar, or perhaps because of it, Taylor was facing increasingly intense prejudice in the States. He had settled in Worcester, Massachusetts, where racism was reputed to be less of a problem. Even so, when he bought land and built a handsome home, he hid his real identity, revealing himself only when the house was completed. “Immediately protests arose,” Taylor reflected in an interview with L’Auto in 1904. “I have bankers and wealthy merchants as neighbours…What audacity! A negro who should live in a hut having

the nerve to settle in such a neighbourhood.”

On the track, rivals employed aggressive tactics to try to stop him winning. He was physically assaulted and authorities tried to block his participation. “Racial relations were very much stressed by the presence of a black rider on the track,” says Ritchie. “Black spectators supported him thoroughly so you had these extraordinary race meetings where he was likely to win against white riders with a very enthusiastic African American crowd supporting him.”

On one occasion his life was threatened. He received a note with a skull and crossbones telling him to get out of town. “Anywhere south of the Mason-Dixon line he just wouldn’t enter,” says Ritchie. It is a revealing sign of those times that even comments attributed to those close to Taylor, such as William Brady, who managed Taylor’s interests for a time and spoke in defence of the rider, are repellent today: “Of course, it is humiliating [for white riders] to have a coloured boy win over them,” Brady is quoted as saying in Taylor’s autobiography. “But Taylor turns the trick honestly and carefully and in racing parlance there is never a whiter man on the track.”

It was against this backdrop that Taylor set sail for Europe in 1901. Over the course of the next three years he undertook three hugely successful tours of Europe and two of Australia. “He went to most European capital cities, racing against most of the European sprint champions, winning 90 per cent of those races,” says Ritchie. It was on his 1903 European tour, or “invasions” as Taylor describes them in his autobiography, that he finally arrived in London for that one and only British race. Why he didn’t race more in Britain is not understood. “I was surprised that the London Canning Town visit was apparently the only visit that he made to the UK,” says Ritchie.

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

Taylor didn’t race on Sundays until the very end of his career – on his arrival in Paris in 1901 he had said, “I swore to my pastor I’d never race on the Lord’s day and I don’t want to go to hell.” Instead, Taylor challenged riders who won those prestigious events to mid-week races, claiming vast sums in the process – his 1902 European tour was reported to have earned him £1,545 (around £200,000 today) in prize money and he was paid £3,000 (nearly £375,000) just to go to Australia in early 1903.

Wherever he went he received constant reminders of being the odd man out. Races were billed as white versus black; riders ganged up on him; newspapers ran racist cartoons. The fact that it is all but impossible to find a newspaper report or feature on him that doesn’t reference his colour is telling. In the eyes of the world, this was a man defined first and foremost by the colour of his skin.

When Taylor returned to Worcester from Australia in 1904, he was a shattered and broken man. Needing rest, he reneged on a contract, giving the cycling authorities in the States the perfect excuse to expel him and retract his racing licence. It would be three years before he raced again, returning to Europe for two more tours before hanging up his wheels. In retirement, with the Great Depression looming, he lost his fortune, family and home. He died in 1932, estranged from his family. “Major Taylor, Dies Penniless … Once Startled World on Bicycle Track,” ran a headline in the Chicago Defender.

“This is the question that fascinates me when you look at his life,” says Lynne Tolman from the Major Taylor Association (see box). “During his career he didn’t often get on his soapbox, he was just trying to win races, earn money and make his career. But when he wrote his autobiography, he was quite clear that he had been treated unfairly. All he wanted was a ‘square deal’, as he called it.

“There’s a sociologist named Harry Edwards who talks about the waves of athlete activism, the fight for legitimacy and access and dignity. Major Taylor embodies these struggles. He faced closed doors and open hostility with remarkable dignity,” concludes Tolman. “Some call him the Jackie Robinson of cycling but Major Taylor came half a century before. Jackie Robinson should be called the Major Taylor of baseball.”

A fitting legacy - The Major Taylor Association

Established in the late 1990s, the Major Taylor Association was formed when locals in Taylor’s adopted home city of Worcester, Massachusetts, wanted to erect a statue in commemoration of his achievements. “That was our first goal,” says Lynne Tolman, president and executive director of the volunteer-run, non-profit organisation. “It took us about 10 years to raise the money and the statue went up in 2008.

“Our mission is to continue to educate people about the life and legacy of Major Taylor and do good works in his name,” Tolman adds. Today, the association works with cycling clubs and schools throughout the US and organises the George Street Bike Challenge – an annual hill-climb on a steep street that Taylor used to ride, which attracts hundreds of riders each year.

“He opened doors and if you take the long view now, more than 100 years later, who walked through them?” continues Tolman. “Cycling at the elite level remains very white so there are a lot of questions still to explore.”

What does Tolman see as Taylor’s legacy? “To keep the conversation going and to further the pursuit of diversity and inclusion and, crucially, equity,” she says. “In what neighbourhoods are bike lanes getting built and who is using them? We’ve all heard of how black drivers tend to get stopped more, arrested more and get harsher sentences and that happens for people on bikes too. These are equity issues.

“Major Taylor is an inspiration for black people who think cycling may not be for them,” concludes Tolman, “but he is also the starting point for conversations about changing cycling.”

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

You can subscribe through this link here.

That way you’ll never miss an issue.