Five lung-busting British climbs that no bike race has dared to use for a summit finish... yet

There are summit finishes no major race in Britain has dared go to, but Simon Warren has. And he’s eager that you, and the pros, should too - Photos by Chris Catchpole

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are probably a myriad of perfectly good reasons but there’s no escaping the fact that last year’s Tour of Britain, was, well, a bit flat, and let’s be honest flat doesn’t entertain anyone, not until the final kilometre at least. What we bike racing fans want are hills, big hills and more than that we want, we demand, a proper summit finish.

There have been a few in our national tour in recent years and granted they provided spectacle, but we could do better, much better. Out there lie roads that could truly entertain, climbs so long and high that they would not look out of place in a Grand Tour and it’s about time we used them.

Alright, there may be some legal issues, some forms to fill in, people to pay off but that’s stuff for men in suits to work out between themselves, all we need to ask is, “Would the Vuelta a España use them?” If the answer is yes, and it’s always yes, then we must use them.

Every year the Tour of Spain’s organisers seem to unearth a climb steeper, more remote and downright crazier than the year before. If it’s paved, if it’s wide enough for a car and finishes at the top of the world then it’s fair game, so it’s about time we followed their example. Of course there are certain practicalities that need consideration — room at the top for a finish line, space to get the infrastructure up — but remember, where there’s a will, there’s a way.

So what are you waiting for Tour of Britain? Let’s use the natural resources at our disposal, let’s squeeze more out of our topography, let’s send our national tour to the top of a crazy mountain top and let’s make Britain’s tour great again.

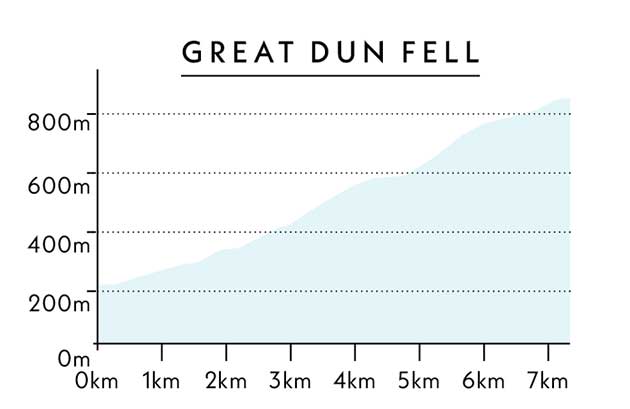

Great Dun Fell

Height gain 638m

Total climb distance 7.45km

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Average gradient 8.6%

This is the big one, Britain’s answer to Mont Ventoux, a true giant, and to think that it’s never been used in our national tour is just criminal. If you knew there were 7.5 kilometres of epic mountain road out there then why would you not use them? Every year! Never mind the gates, sheep, farm machinery, gale force winds, horizontal rain and likely chance of hypothermia, this ‘venue’ has summit finish written all over it.

Most British climbs are done and dusted in a few minutes; Great Dun Fell has a KOM of 25 minutes, which makes it two thirds of an Alpe d’Huez. It’s just awesome to ride, and awesome to look at.

National tours are all about showcasing the geography of your country. Why do you think we get all those sweeping helicopter shots of French valleys and Spanish olive groves on TV — so we pack our bags in the summer and go visit them.

Without wanting to offend the residents of the flatter parts of our island, the scenery there is not exactly going to be attracting legions of Europeans across the channel to spend their good money here. Show them the vast rolling peaks of the Pennines though, sweeping up the spine of the country into the Lake District and we might be on to a winner.

Anyway, back to the climb, and it is a climb, a proper climb. The sort of climb that has sprinters organising an autobus before they have left the breakfast table. Not just a ramp they can power over but an ascent of such magnitude that they have to huddle together for safety to avoid missing the time cut.

>>> Tour of Britain 2018: Latest news and race info

As I begin the climb I see my target, the giant ‘golf ball’ radar station perched at its summit and it looks a very long way away. The road ramps up steep right from the gun, a taster of things to come, a warning to the legs that if they are faint-hearted then now is the time to turn back. Once through this initial tough stretch the climb eases up to the first of two gates.

Sometimes open, sometimes shut, you pass through, over a cattle grid and into more hard work. Higher up there’s a break in hostilities as the slope levels, before ramping up to over 20 per cent again. This is the part that will separate the mountain goats from the pack.

Passing the sign that bars public cars any further access I reach the wonderland at the top. From here to the summit a beautifully smooth, incredibly narrow road, lined both sides with snow poles winds it way to the peak of the fell.

To begin with it’s close to 25 per cent but soon after it eases, as over the horizon, rising like a giant white sun the radar comes into view. Through the second gate, it’s wild and exposed, the views are tremendous then there’s one last killer ramp to the finish at the top of the world.

Ride it for yourself

A good place to start is Brough as there are plenty of hotels, cafes and restaurants. To build the climb into a challenging route first head north-east out of town over Shot Moss, then turn left onto the B6277 to ride over Yad Moss into Alston. From here head south-west on the A686 over the Hartside Pass to Melmerby, then turn south to Knock, head up and down the Great Fell then home, via Appleby-in-Westmorland. Distance: 133km Climbing: 2,366m

Would the Vuelta use it?

They would build a road going down the other side and run a crit on it. I think 10 laps would shake the peloton up.

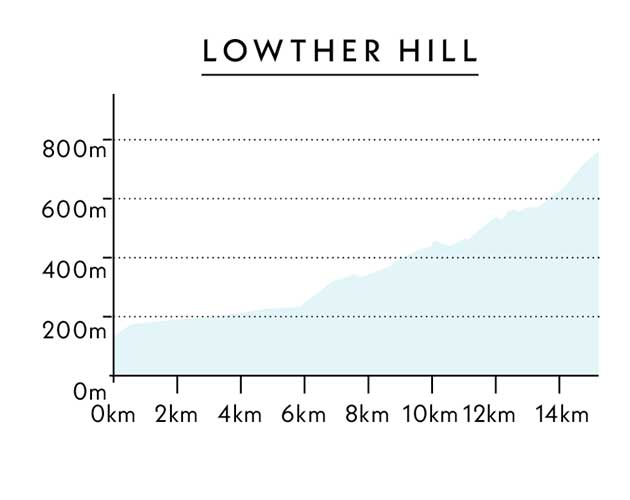

Lowther Hill

Height gain 594m

Total climb distance 14.8km

Average gradient 4%

This was my inspiration for this piece. As soon as I first arrived at the top I just knew it would make the perfect venue for a summit finish and decided to make it my mission in life to tell everyone.

Let’s look at the raw stats first. From the base in Mennock to the radar on top of the hill the road climbs for 14.8km; that’s a whole kilometre longer for example, than the famous Pyrenean ascent to Luz Ardiden.

Over that 14.8 kilometres it gains a whopping 594m in elevation with a maximum gradient of 16 per cent, so not only is it long, it’s also pretty steep in places. Leaving Mennock the first 11km are quite tame, OK, it is longer than Luz Ardiden, but that’s where the comparison’s end unfortunately.

Instead of a punishing 7.9 per cent average, the Mennock Pass, which forms the first 11km of the climb, only has an average of just over three per cent. Don’t for one moment go thinking that it will be easy though, it’s still an 11-kilometre climb and should do an excellent job of shedding all but the top GC riders and their domestiques to fight out the finale.

Imagine a race in the UK where a team puts its climbing domestiques on the front to soften the peloton up before the last 3km of a climb. That’s what happens in France, Italy and Spain, not Britain.

Once the Mennock Pass is under my belt I’ve passed through Wanlockhead (Scotland’s highest village), it’s here the fun starts. Leaving the main B797 is the service road up to the radar station. I say service road but this is no single carriageway gravel track, oh no, this is a smooth-as-silk, twin-lane jewel of a road, doubtless better than many you train on day in day out.

Sweeping over the contours of the interlocking hills, writhing ever upwards, it bends and weaves, rises and falls in search of its summit. There are sharp spikes in gradient, long draining drags, tight corners, false summits, in fact it has everything I could wish for to make it the perfect race venue.

>>> Which is faster – climbing in or out of the saddle?

With legs well softened from the Mennock Pass the early part hits you hard, there’s a rapid rise away from the main road, and it then eases somewhat before reaching a small descent. Ahead there’s a collection of radio masts, a staging point on the way to the summit and to reach them the road becomes much harder to climb. It’s here that it hits its maximum and it’s here that I imagine an all-out war to the top would start.

Rounding the tangle of towers the climb enters its final few twists and turns before the gradient evaporates on the large plateau on top of the hill. Surrounded by the most wonderful scenery and at the top of a 15 km climb I feel the need to pinch myself. Am I still in Britain, does this really exist? Yes I am, and yes it does, so bring on the bike race.

Ride it for yourself

To incorporate it into a good ride base yourself in Moffat where you will find all the amenities you need, then head north on the A701, B719 and B7076 to Abington at junction 13 of the M74. Head west through Crawfordjohn over the B740 and then down into Sanquhar to follow the A76 south to Mennock. Turn left then ride the 14km to the summit before returning down to the main road then continuing north-east through Leadhills, to Elvanfoot, then back south to Moffat. Distance: 110km Climbing: 1591m

Would the Vuelta use it?

They probably have, we just thought we were watching pictures of someone in Spain, not the Scottish Borders.

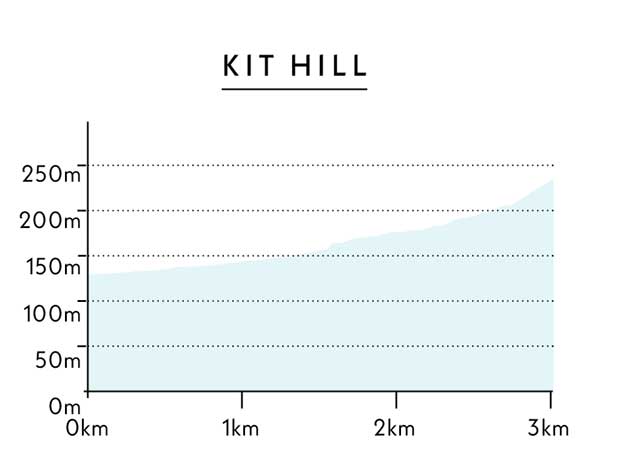

Kit Hill

Height gain 293m

Total climb distance 3.4km

Average gradient 8.6%

The shortest of the five but the one with the most relentlessly tough gradients. For miles around you can see the monument that sits proud on top of Kit Hill, keeping a watchful eye on all below and guiding you to its summit.

For maximum effect start the climb in the village of Luckett just inside the Cornish border, cross the stream and face up to the wall in front of you. For what seems like an age the road screams upwards at 20 per cent before easing, very briefly, then heading straight back in to more brutal climbing.

Only when you reach the trees do the steep slopes finally recede but by now the damage is done.

Crossing the B3257 there’s yet another 20 per cent ramp, followed by a lull before the narrow road up to the monument begins. Rough and punctuated with rudimentary speed bumps it’s a challenging end to a savage climb but all pain is numbed by the simply outstanding views.

Sitting high above the Cornish landscape Kit Hill is a truly special place offering a 360-degree panorama of patchwork fields as far as the eye can see.

Ride it for yourself

Make camp in Launceston and from there head south via Old Greystone Hill to Milton Abbot then continue south to Luckett. Head up and down Kit Hill, then to return head north-west to Kelly Bray and back via Trebullett into Launceston. Distance: 46km Climbing: 960m

Would the Vuelta use it?

Is the Pope a Catholic? Is the sky grey?

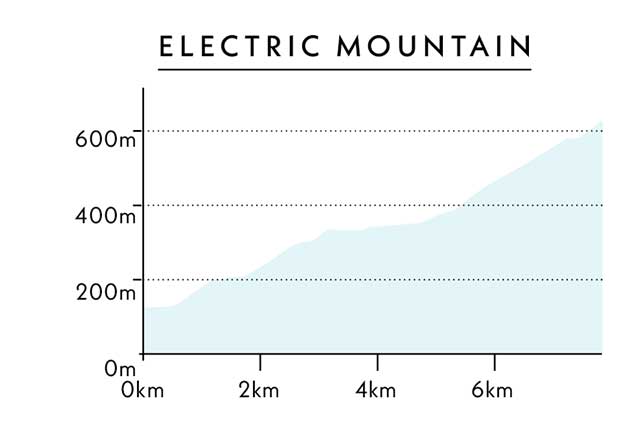

Elidir Fawr / Marchlyn Mawr / Electric Mountain

Height gain 524m

Total climb distance 7.8km

Average gradient 7%

With twisting bends and vicious inclines, this climb to the reservoir in the clouds would spoil you with close to eight kilometres of all-guns-blazing action. Rising away from Lake Padarn the early slopes weave between high stone walls on a gentle gradient passing under gnarled and twisted trees.

To end this opening stretch the peace is shattered by a killer 20 per cent ramp up to a junction, the perfect launch pad for the pros to attack. The mid section is exposed and very shallow in its pitch — time to take stock and prepare for the spectacular finish.

>>> Britain’s Mont Ventoux: climbing the Bwlch the hard way

Rising through pristine grassland, the service road up to Marchlyn Mawr snakes beneath towering rocky peaks as its gradient increases to a testing 10 per cent. If you’d been driven there blindfold you’d be forgiven for thinking you had been dropped in the Pyrenees, it’s that good, a real life mountain road, alas only three kilometres long though.

With a brace of giant sweeping bends and a final steep kick to the finish this awesome climb, set in a giant natural amphitheatre would create a sporting spectacle the likes of which the British Isles have rarely seen and showcase some of Wales’s most dramatic scenery.

Ride it for yourself

Any of the towns in north-west Wales from Colwyn Bay down to Caernarfon would make an excellent base to ride in the area. For this climb I’d choose Caernarfon and to fit it into a nice loop head south on the A4085 to Beddgelert, then head back looping over the Llanberis Pass to save this climb for the finale before heading home. Distance: 71km Climbing: 1,580m

Would the Vuelta use it?

They would, but they can’t because it’s in North Wales and it’s ours.

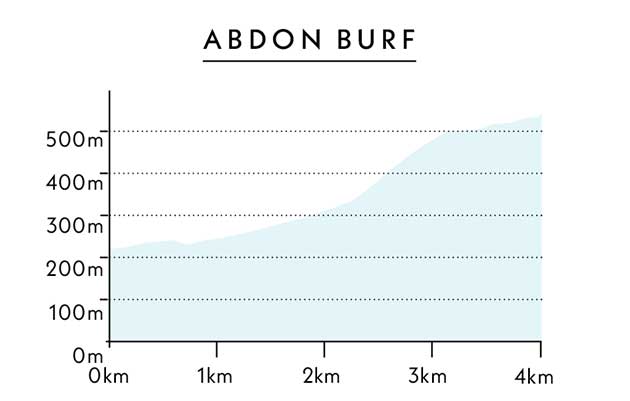

Abdon Burf

Height gain 315m

Total climb distance 3.7km

Average gradient 9%

I’ve been banging on about this climb ever since it forced me to get off and walk three times during a single ascent — and I make a living writing about riding up hills. It’s utterly brutal and just the road to create a spectacle to match anything seen in the Grand Tours.

If you measure the start of the climb from the village of Ditton Priors then you get a total elevation of 315 metres over its 3.7-kilometre length which gives it an average of nine per cent — not too bad, you may think. Well, think again, in the middle of this 3.7 kilometres lie 600 metres of continuous 20-25 per cent gradient. Yes, continuous.

This part of the climb makes the Angliru look like Box Hill. It’s a dead straight line of pure relentless hell. Too tough? Never, not for the world’s best climbers; they will be begging to dance up this hideous slope to entertain the waiting hordes, cameras primed to capture some epic pain faces.

>>> Get better at climbing hills: top tips to speed up your ascents

Once through the brutality of this savage ramp the road arrives at a rolling grassy plateau perched high above the Shropshire hills and continues to climb serenely through this lost world to the peak at the radio masts, the highest point for miles in all directions.

Ride it for yourself

To ride Abdon Burf base yourself in Church Stretton as there plenty of places to eat and sleep; you also have the Long Mynd on your doorstep so you can take on the Burway and Asterton Bank. To ride Abdon Burf head west on the B4371 to Wall under Heywood then head through Rushbury, Broadstone and Holdgate to Ditton Priors. From here you can ride the full length of the climb before retracing your steps to Church Stretton. Distance: 52km Climbing: 1,140m

Would the Vuelta use it?

If they knew it existed they would have it transposed from the Shropshire hills to Asturias and claim it as their own.

A word of warning!

CW photographer Chris Catchpole and rider Hannah Bussey originally went to shoot for this piece in April but it didn’t really go according to plan.

“It was kind of ridiculous,” says Chris. “It was fine for the first five minutes, then we came to a snow drift, I tried to drive over it and got the van stuck. We freed the van and I had to reverse half a mile.

"We decided to walk up but it was unrideable. Then we met a snow plough coming down and he said I had to move the van so we had to retreat again. He didn’t even clear the snow!”

Simon has been riding for over 30 years and has a long connection with Cycling Weekly, he was once a designer on the magazine and has been a regular contributor for many years. Arguably, though, he is best known as the author of Cycling Climbs series of books. Staring with 100 Greatest Cycling Climbs in 2010, Simon has set out to chronicle and, of course, ride the toughest cycling climbs across the UK and Europe. Since that first book, he's added 11 more, as well Ride Britain which showcases 40 inspirational road cycling routes. Based in Sheffield, Yorkshire, Simon continues to keep riding his bike uphill and guides rides, hosts events and gives talks on climbing hills on bikes!