Tom Dumoulin: Olympics, not Grand Tours, my main focus in 2016

As a time triallist with Tour hopes, comparisons with Sir Bradley Wiggins are inevitable, but the 25-year-old Dutchman is very much his own man

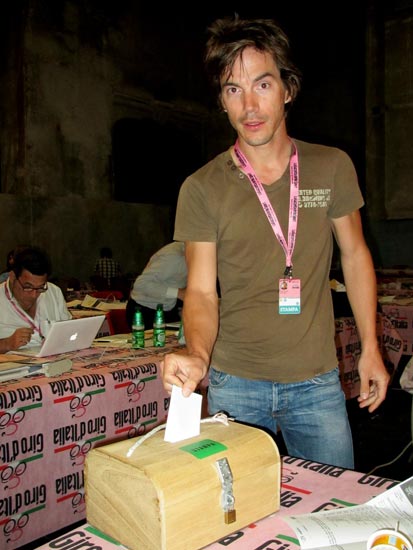

Tom Dumoulin

Wearing the red leader’s jersey of the Vuelta a España, Tom Dumoulin rode over the finish line and to his white Giant-Alpecin team car. The press surrounded him as he sat down.

He looked up at the leader board above the podium. It showed that he had lost the race by three minutes and 46 seconds to Italian Fabio Aru of Astana. But it failed to relay the bigger message: the birth of a new Grand Tour star.

The then 24-year-old Dutchman from Maastricht had surprised and survived in the three-week Spanish Grand Tour. Many had only first heard his name before at the World Championships in Ponferrada last year, when he took the last podium step behind time trial victor Sir Bradley Wiggins and Tony Martin.

Even when the Vuelta kicked off in Puerto Banús in late August, he was still considered a time trial specialist, not a Grand Tour contender.

His ride at the Vuelta drastically changed the landscape. The Dutch have seemingly forgotten about Bauke Mollema, Robert Gesink and Wilco Kelderman, and now put their hopes on Dumoulin.

>>> Robert Gesink smashes Strava KoM on Tour de France’s first mountain

The newspapers in the Netherlands fill pages with stories about his new contract extension to 2018, and his Grand Tour and Olympic plans.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The message is simple, and 6ft 1in dark-haired Dumoulin spells it out when he sits down with Cycling Weekly: “I hope to one day win a Grand Tour.”

Mr Consistent

Dumoulin leapt into the imaginations of cycling fans on stage two of the Vuelta. If he could break free from the main contenders with small Colombian Esteban Chaves then what else could he do? The answer came over the following three weeks.

He placed third in another summit finish and climbed to win the Cumbre del Sol stage ahead of Sky’s Chris Froome.

His Giant-Alpecin team then said that the biggest test would be if he could perform consistently over three weeks. He did. By the first rest day and at the end of a big mountain block, he sat fourth overall. In the time trial in Burgos two days later, he won the stage and took the red jersey.

Dumoulin only failed to win the Vuelta at the final hurdle: the stage to Cercedilla, north-west of Madrid. Succumbing to attacks by Aru and his gang of Astana team-mates, he became isolated, and rapidly lost time.

Had he only survived that penultimate stage then the big Dutchman would have won the Vuelta. Had Giant brought a Grand Tour team rather than one for fastman John Degenkolb, they might have been able to defend him. Had this or that happened then the results board might have read differently.

What the Vuelta showed, however, was that Dumoulin is a time triallist who can still push big watts even if he loses weight. He weighed 70kg at the Vuelta and according to data the team released, at the end of a three-day mountain block, he was still able to generate 6.1 watts/kg over a 25-34 minute climb.

>>> Dumoulin power data reveals true story of Vuelta a España ride

Comparisons were immediately made to Wiggins, a time triallist who morphed into a Grand Tour rider.

“It might look like that a little bit,” he says, “but I’m still Tom Dumoulin and not Bradley Wiggins. I’m not trying to become Bradley Wiggins.”

Impression

There was something very human about Dumoulin’s Vuelta ride. Many who have ridden bikes know what it is to suffer, to maintain your place in the group only to crack at the last moment.

Dumoulin’s performance contrasted with the apparent invincibility of some Grand Tour contenders. According to Dutch journalist Raymond Kerckhoffs, Dumoulin considers himself “an

atypical cyclist”.

A Limburger, Dumoulin grew up next to the Amstel Gold Race’s old finish straight on Maasboulevard in Maastricht. His family had no history in cycling. He played football at first. But the race helped draw him in.

“I cannot name one factor of why I started cycling, but if I had to then it would be the Amstel Gold Race,” Dumoulin says.

“I didn’t know anything about cycling, but that really got to me. I thought it was cool as a little boy with the helicopters, cyclists and colours.

“When you are standing on the side of the road, with the helicopters in the distance, then the first cars pass and then the riders fly by — it’s special. And as a little kid, it makes an impression.”

Learn how to pace your TT

Almost as if he’s followed the event, Dumoulin now lives with his girlfriend in Valkenburg near where Amstel Gold finishes these days. He says that he keeps trying to win the race, but “it never works out”.

He was given his first chance on the international stage when the national team took him to the 2010 Grand Prix of Portugal, part of the under-23s Nations Cup.

Having never ridden an aero bike before, he won the time trial stage on one he’d borrowed from a team-mate and held on for the general classification win the next day. Later that year, he won another time trial in the amateur Giro d’Italia.

“Maybe I’m atypical because I didn’t grow up with cycling and I had to find it out on my own,” he says. “I guess I’m starting to become a typical cyclist as the years go on.

“It wasn’t ever my childhood dream to become a pro cyclist. Even when I started, it was never a plan to make it my profession and to make money. I was just cycling for fun. The dream was only there when I reached a level where it looked to be possible.”

Dumoulin had planned to sign with the Cervélo professional team, but the brakes were put on that when they were assimilated by Garmin.

Instead he signed for Rabobank’s development team for two years but left after one for Giant-Alpecin’s forerunner, Argos-Shimano.

Since joining the squad in 2012, Dumoulin has won time trials in the Critérium International, the Eneco Tour, Tour of the Basque Country, and this June, two in the Tour de Suisse.

The Swiss results helped him place third overall behind winner Simon Spilak and Sky’s Geraint Thomas, and offered a hint of things to come.

This year Dumoulin put all of his weight behind the Tour de France and attended an altitude training camp in Sierra Nevada, Spain. His goal was a spell in the yellow jersey.

Although he could only place fourth behind winner Rohan Dennis on Dutch soil in the opening time trial, Dumoulin hoped he could climb into the yellow jersey at the end of stage three on the Mur de Huy.

However, a mass high-speed spill on the way forced him to abandon with a dislocated shoulder. Going to the Vuelta was an attempt to salvage his summer.

Eyes on Rio

Before perceptions altered at the Vuelta, Dumoulin had said that his aim was to win a gold medal in the time trial at the Rio Olympic Games. His Grand Tour status may now have changed, but his outlook hasn’t.

In 2016 Dumoulin may race a Grand Tour, but he might also avoid the stressful classification fight. To some experts, that would be a shame.

“Everyone can see that he’s a very good time triallist. He’s been good for a long time, but when you can take that time trail ability and use it to go uphill you become a very potent force in stage racing,” Team Sky’s principal, Sir David Brailsford, observes.

>>> Dave Brailsford: Tom Dumoulin should aim for Tour de France

“We won the Tour and the time trial in London 2012 back-to-back, and we know how to do that. You have to shoot for stars and get to the moon,” Brailsford continued.

Alberto Contador, winner of seven Grand Tours, also sees Dumoulin’s potential: “In the Vuelta he was very strong, incredible, even if his team wasn’t ready.

“The Giro would be very good for him,” he adds (Contador himself plans to target the Tour and Vuelta next season). “There are two very good time trials. If he’s at the same level as he was at the Vuelta, then he has a big chance to win.”

Aiming for the Olympics requires a delicate juggle of trade team and national commitments. Racing in your country’s colours and on a blacked out bike in the Olympics is too much for some.

For example, Etixx-Quick Step boss Patrick Lefevere said that he did not want Mark Cavendish to skip races to focus on racing for Great Britain — hence the move to MTN.

>>> Cavendish: I see Dimension Data becoming the biggest team in pro cycling

“[Dumoulin] put the Olympics out there as a big goal, but he has other goals, as well,” Giant sports director, Aike Visbeek, reasons. “It has a special place in his heart. He has one or two chances to win a gold medal there.

“We support that. Winning a gold medal is important for our team. What makes it different is we can help and support our rider to get there, but we are not at the event itself.”

Visbeek adds that the team needs to examine the Giro and Tour routes to decide which is best. Passing up an ideal Tour route, Visbeek says, would be impossible, but Dumoulin is unbending.

“Rio is my main focus,” he asserts. “It’s difficult to say how the approach in the rest of the

season will be, but I’ll definitely need to be 100 per cent in Rio and possibly be 100 per cent in the other parts of the year.

“Maybe it’s possible to be 100 per cent in a Grand Tour and 100 per cent in Rio.”

Experience

Much depends on this winter and how Dumoulin comes out of it for next season, and 2016 could shape the remainder of his career.

Dumoulin brought down his weight for 2015 to test his limits. He wanted to see how low he could go without affecting his time trialling. He found that he could not only climb better, but time trial faster too.

>>> Chris Froome described as “close to human peak” after physiological data release

“I really want to keep my TT as my main focus — my main weapon,” Dumoulin says.

“If being a Grand Tour rider means losing my capability of riding a good TT, then maybe I won’t do it. It’s about looking for the right balance between power and weight.

>>> The importance of power-to-weight, and how to improve yours

“In the Vuelta, I was still not on my limit in terms of weight loss. It’ll still take some time. I’m 24 and I don’t want to lose a lot of weight drastically. Over three years, I could lose one or two kilograms.”

Visbeek places gaining experience above losing weight, though. “We have little capacity to lose more weight — that is not a significant gain to be made,” he says.

“The main progression comes from riding more Grand Tours, getting stronger, riding for the GC in the third week. He has to do that one or two times more to get experience.”

Though the Vuelta came late in the season and left little time to manoeuvre, Giant is circling its wagons around Dumoulin and Frenchman Warren Barguil for a more classification-focused team.

This autumn, it extended their contracts through to 2018 and let go of sprinter Marcel Kittel.

The message appears clear: Dumoulin will time trial in Rio and, even if not this year, race for Grand Tour glory in the future.

>>> Marcel Kittel: I’m not taking Cavendish’s place, but starting afresh

He, understandably, may not be keen on the Wiggins comparisons but they’re somewhat inevitable.

“If you want to talk about a time triallist becoming a Grand Tour rider, then Bradley Wiggins might be the closest comparison,” he says.

But he adds: “The only cyclist I had heard of when I was a boy was Michael Boogerd. It’s not like he was my idol; I didn’t have a poster of him next to my bed.

“When I turned pro, I always looked at big riders and how they did things: trying to learn how they trained and prepared for a race. I never had one who was my idol, though.

“I don’t want to mirror any other rider, and definitely not the biggest riders,” he concludes. “I have to make my own career.”

Gregor Brown is an experienced cycling journalist, based in Florence, Italy. He has covered races all over the world for over a decade - following the Giro, Tour de France, and every major race since 2006. His love of cycling began with freestyle and BMX, before the 1998 Tour de France led him to a deep appreciation of the road racing season.