The story of Britain's first-ever Tour de France team

Sixty-five years ago Britain sent a full team to Le Tour for the first time. Giles Belbin tells the story of Team GB’s historic debut

Team boss Cozens chats to his riders (clockwise from top left): Steel, Maitland, Hoar, Robinson, Mitchell and Krebs (Photo by Bert Hardy/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The night before the final stage of the 1955 Tour de France, Britain’s Brian Robinson and Tony Hoar couldn’t sleep. Behind them were 4,247km of tough racing, crashes and punctures; three weeks of cobblestones, mountains and desperate chases. Now, ahead lay only 229km more, from Tours to Paris and a final sprint on the famous Parc des Princes track.

Robinson and Hoar tossed and turned all night. Earlier that day both had raced into Tours at the end of a 68.6km time trial from Châtellerault, Hoar besting Robinson by 1min 22sec. But it was Robinson who held the advantage overall, lying some 40 places higher up the general classification. Whether it was adrenaline from a day spent racing against the clock, or a nervous sense of anticipation at becoming the first British riders to complete the Tour, that kept them awake is not clear. Perhaps the two riders were fitful and restless due to the noise from the post-stage parties that lasted long into the night. "Tony Hoar and I had not slept a wink when we set out on this remarkable adventure," Robinson would later say when reflecting on the special experience of riding the Tour’s final stage.

At last dawn finally broke. It was 30 July, a Saturday. In the coming hours the Tour would celebrate its second three-time winner – Louison Bobet who had entered the race as the defending two-time champion. Bobet had taken yellow at the beginning of the final week and lay nearly five minutes ahead of the second-placed Jean Brankart. Barring misfortune or collapse en route to Paris, the Frenchman, who was once considered too fragile for Grand Tour racing, was nailed on to claim his third Tour title

in succession.

As Bobet readied himself to enter the record books, Belgium’s Philippe Thys, the only other rider to have won three Tours (1913/14/20), was making his own way to Paris from the Auvergne, where he had been on holiday, having received an invite from the Tour’s organisers to make a presentation to Bobet and share a lap of honour. Perhaps the Belgian was unaware that, alongside the reported 50,000 spectators that packed the stadium’s stands, he would also bear witness to the first riders from Britain crossing cycling’s ultimate finish line.

Six hours, 38 minutes and 39 seconds after leaving Tours, Robinson and Hoar completed their race, part of a 68-rider bunch that had allowed Spain’s Miguel Poblet to escape and claim a 14-second solo victory. While Bobet was the focus of France, the reaction of the Parisian crowd to the two Britons was warm.

Robinson, who finished 29th overall, had featured strongly in a number of stages over the course of the race, performances which had earned him the respect of fellow racers and seasoned Tour watchers. Hoar, meanwhile, was 69th and lanterne rouge, coming home nearly an hour behind the 68th placed rider, Henri Sitek of France. He had ridden with doggedness and good humour throughout and his arrival in Paris was as roundly celebrated as it was unexpected – halfway through the race the British press having reported that he surely couldn’t last much longer. And it was true that Hoar had enjoyed the benefit of the doubt along the way. After failing to make the time limit into Monaco, a stage that took in the climbs of the Vars and Cayolle during which he fell three times, he was allowed to continue, having been found to have been disadvantaged by traffic that spilled onto the race route before he passed.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

In Paris, Hoar rode his lap of honour with a small red lantern attached to his bike to a soundtrack of French voices calling his name. Then he posed for the customary photograph alongside race winner Bobet. "The young Hampshire cyclist has become almost a legend due to his grim determination to compete the Tour at all costs," reported the Aberdeen Evening Express. "All along the route the cheering French crowds have first looked out for their own idol, Louis Robet [sic] … and then for Hoar who has been battling against the odds since the early stages." In Paris, Hoar, dubbed ‘Tail-end Tony’ by the British press, reflected, "It was the toughest race I’ve ever been in...I kept on plugging away because it was worthwhile finishing."

As for Robinson? Well, he had truly impressed. Jock Wadley wrote in the pages of the inaugural edition of Coureur that "the Recce Tour found [Britain] a leader for ’56". "I’ll be back," Robinson said in Paris, and indeed he would.

The Hercules connection

Charles Holland and Bill Burl had been the first Brits to ride the race in 1937, in a three-man ‘team’ alongside the Canadian Pierre Gachon, but they rode with no real support and neither rider finished. The idea of taking a full and supported British team to the Tour had formed at the 1953 World Championships in Switzerland.

It was there that a group of influential voices, including the editors of Cycling and The Bicycle, began to discuss the merits of sending a squad of British riders to the Tour. Among those contributing to the group’s discussion was D.D. ‘Mac’ McLachlan, director of publicity for bike brand Hercules. Hercules sponsored a professional road team and with talk turning to the Tour, Mac sensed a golden publicity opportunity – while any team at the Tour would have to ride in national rather than trade colours, Hercules could only benefit by association.

The Tour organisation was keen and in November 1954 agreement was reached for a British team to enter the race. In early 1955 Hercules sent their riders to the Côte d’Azur to train and get much needed European race experience, intent on maximising their participation in the Tour. The ploy worked. "Ten cyclists to represent Great Britain for the first time in the Tour de France from July 7-31 [sic] were named yesterday," reported the Birmingham Daily Gazette on 14 June. "They are: Dave Bedwell (Romford), Tony Hoar (Emsworth), Stan Jones (Birmingham), Fred Krebs (Cambridge), Bob Maitland (Birmingham), Ken Mitchell (Kenton), Bernard Pusey (Redhill), Brian Robinson (Huddersfield), Ian Steel (Glasgow) and Bevis Wood (Manchester)." Six of those 10 – Bedwell, Hoar, Krebs, Maitland, Pusey and Robinson – rode for Hercules, while the team was led by Syd Cozens, the Hercules manager.

Twenty-four days later those 10 men stood to La Marseillaise and paraded along the seafront in Le Havre. How they would fare over the coming weeks was a complete unknown. L’Équipe reported the team to be "richer in courage than experience," while the Birmingham Daily Gazette claimed the team’s mere presence in France as "acknowledgement of our riders’ world class". Over at the Daily Herald, Sydney Saltmarsh reported: "Have we a chance? Frankly, no…if some of them are even among the finishers they will have done well," before changing his mind and writing five paragraphs later that Bedwell’s "devastating sprint may well snatch one of the early stage wins".

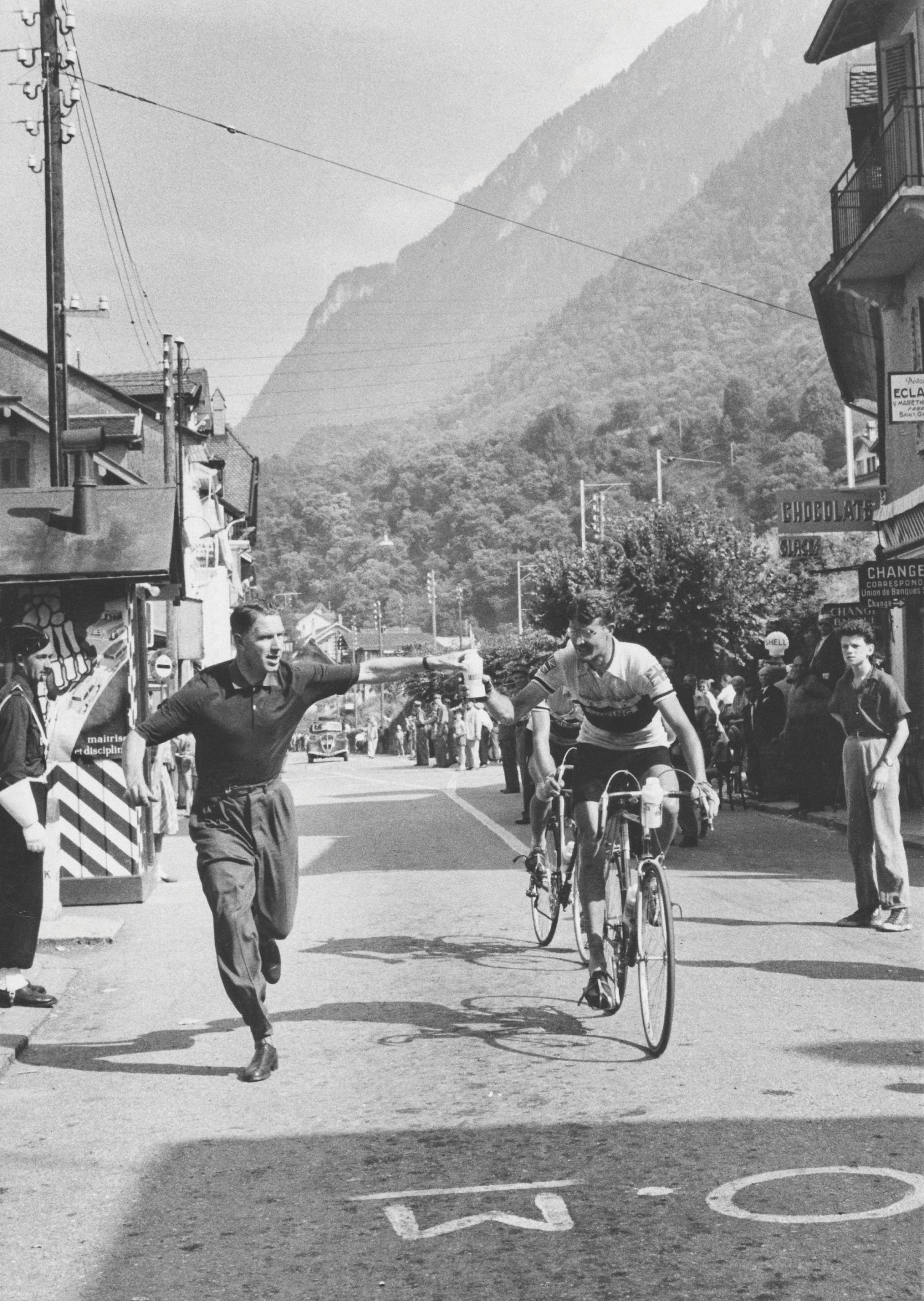

As it turned out the team suffered right from the off. Just three stages in and Pusey, Bedwell and Wood had already packed, having missed time limits. There was tension within the team, with some considering Cozens out of his depth. "Syd was fluent in French but that was almost the only good thing about him," Hoar told Max Leonard for his book Lanterne Rouge. "He didn’t know anything about road racing." They also suffered frequent punctures. On the first day, 30 seconds before starting the afternoon’s team time trial, Bedwell noticed his front tyre was flat. As he tried desperately to inflate it, the valve blew on the pump, meaning there was no choice but to change the wheel and then ride the course alone. "The tyres were s**t," Robinson reflects bluntly in William Fotheringham’s Roule Brittania.

The team had been assured the Dunlop tubulars were mature, "but we had more punctures than any other team," Hoar tells Fotheringham. "We all got p***ed off with it, so we cut them open – they had the date stamped on the inner tubes and they were only a few months old."

Robinson turns heads

As the race progressed, so the team disintegrated. Jones was eliminated on stage seven; Steel climbed off, exhausted and disillusioned en route to Briançon; Maitland crashed out on stage nine, with photographs showing him sat on a wall with a bloodied elbow and knee while a cooking-apron-wearing housewife cleans his wounds. Krebs and Mitchell started stage 11 over Mont Ventoux – an infamous day in Tour history when Bobet rose over the Giant of Provence in severe heat, Jean Malléjac collapsed, and a disorientated Ferdi Kübler weaved up and down the mountain. Both Brits dropped out before reaching Avignon, with Mitchell suffering from a saddle sore so severe he had cut sections out of his saddle. With 11 stages still to go, now there were two.

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

Despite the team’s travails, Robinson was performing admirably. "Up through that narrow torture chamber climbed Robinson, suffering like I’ve never before seen an English bike rider suffer, yet somehow preserving his outstanding poise and style…'he passed 39 riders on the way up,'" wrote Jock Wadley, quoting Viking team manager and acting British team mechanic Bob Thom, who had counted the riders. Robinson was equally as impressive in the Pyrenees. "Experienced observers say they have never seen anything to equal Brian Robinson’s flying descent of the 5,500ft Aubisque," reported the Herald somewhat improbably. Whatever the truth of that statement, Robinson enjoyed a successful final week, rising 10 places to finish 29th overall in Paris.

Hoar may have captured many of the headlines and photographers at the finale – such is the romanticism of the lanterne rouge – but it was Robinson who had turned the heads that mattered. Two-time Tour winner André Leducq told the Yorkshireman he "could finish in the first 15 of the Tour next year," which he duly did, riding into Paris in 14th place 12 months on.

In 2014 Robinson spoke to Kirklees Local Television, saying that Bobet had told him during that first Tour adventure, "It’s not like jumping up a step coming to France, it’s like going up a whole storey." Of the 10 that lined up in Le Havre that July day in 1955, it was only Robinson who would return, riding seven Tours in total and becoming Britain’s first stage winner.

They may not all have had the head for such prolonged heights but the class of ’55 truly blazed a trail. "Only two completed the course," concluded this publication, "but these two have shown in this, our preparatory year, that they and others will ride faster in these wheelmarks in years to come."

Sixty-five years on, and with Britain having since laid claim to 71 stages as well as successes in every major classification including six overall victories, it may have taken a little time but there never was a truer word written.

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.