From Millie Robinson to Pauline Ferrand-Prévot - how the Tour de France Femmes has been 70 years in the making

The first women's Tour de France took place in 1955, but the path to today's Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift did not run smoothly

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Forty years on, Clare Greenwood is ready to share the real reason she attacked on the Champs Élysées. "I'd had a bidon that had lasted me the whole three weeks," she says. "I decided: Right, I'm going to act like one of the guys - I'm going to finish my drink, then toss it to the crowd". On one of the most iconic roads in cycling, with 'Great Britain' emblazoned over her heart, Greenwood did just that. But the move backfired. "It hit a lamppost and ricocheted back into the peloton at the height of everybody's head". She heard a shouted complaint from behind and thought, "Oh hell, I'm in trouble now". Her only means of escape, she figured, was to attack. "Needless to say, it only lasted a few seconds"

The race was the 1984 Tour de France Féminin, the first women's Tour held alongside the men's. Only five editions took place, followed by a decades-long haitus. The women rode truncated stages ahead of the men before being bundled into cars by gendarmerie to clear the finish area.

They were the first women to join what Greenwood calls "the Champs Élysées elite": the few women who have ridden the Tour de France. Another member is Liz Hepple, an Australian Olympian and former professional road cyclist. Before she arrived in France for the 1986 Féminin, she had never descended a switchback, yet she came fifth in the GC. In 1988, having honed her descending to match her climbing power, she came third - the first Australian to podium at the Tour de France

"Everyone assumes we must have been pissed. We probably were, but we had a lot of fun"

Clare Greenwood

"I remember the craziness of the spectators," Hepple says. "You couldn't hear anything because the screaming and shouting were so loud". Greenwood, meanwhile, relied on fans for information: they would run alongside calling out where her rivals were. Supporters also assisted with fuelling on long climbs, offering bread, water and even wine. While she passed on the wine, Greenwood took the water: "That's the only way I made it to the top".

The basic food back then - "to this day, I cannot face a plain Danone yoghurt," Greenwood says - reflected the era's rudimentary sports nutrition. Greenwood tells the story of buying a litre of brandy at duty-free with her room-mate, which they mixed with flat Coke in their bidons, having heard it combatted dehydration.

"Everyone assumes we must have been pissed. We probably were, but we had a lot of fun". Rider support was likewise basic: Hepple was given one summer jersey for the entire race, and there was just one team mechanic.

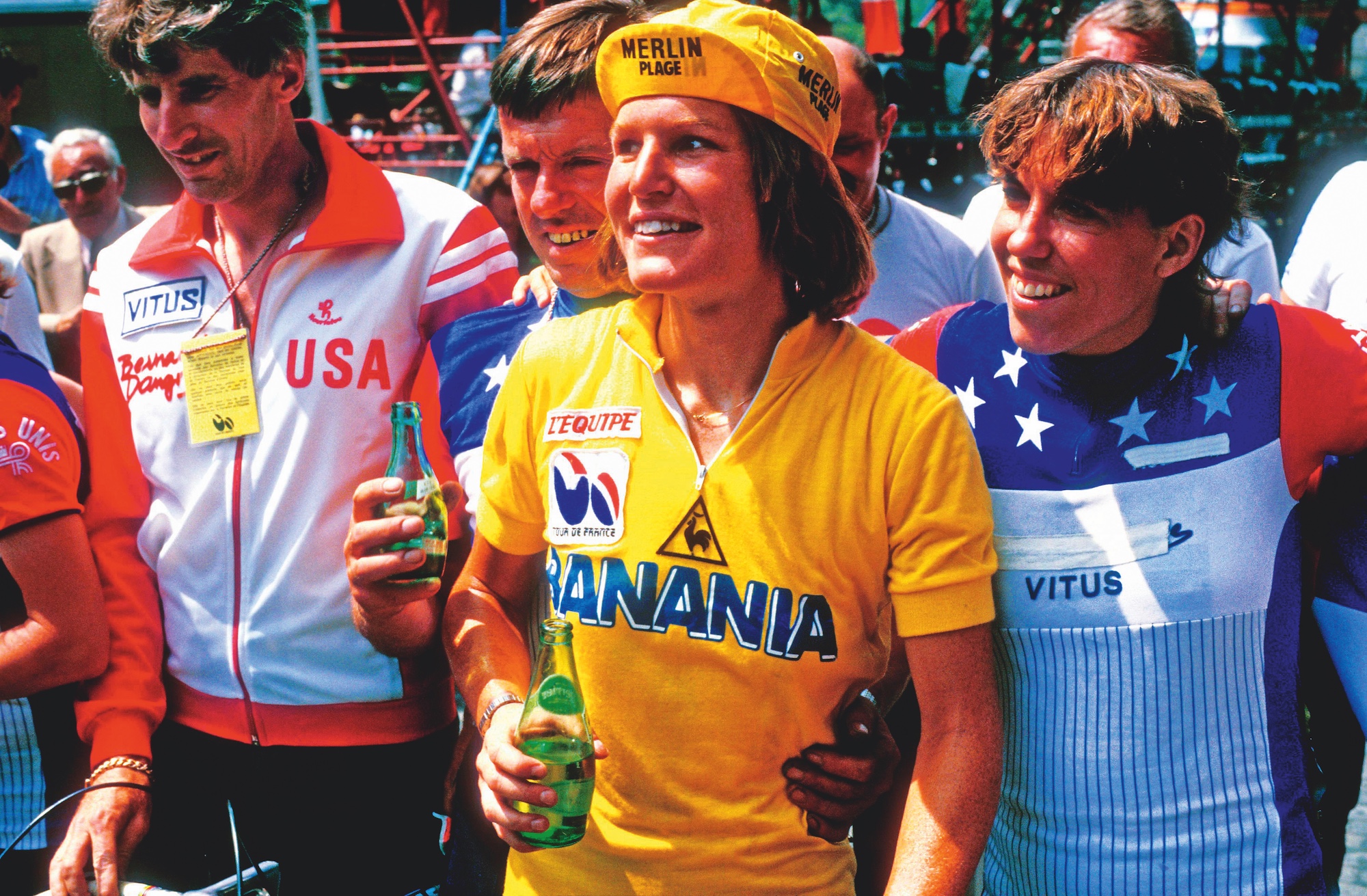

Marianne Martin of the USA winning the first Tour de France Féminin in 1984

When Greenwood arrived back in England after the 1984 race, she went to a branch of WHSmiths and "almost dropped dead" to see herself on the cover of Cycling magazine in her Great Britain jersey. Years later, she found a copy on eBay advertised for just a pound.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Tour de France Femmes Trailblazers

Here's a quiz question: Who was the first Brit to bring home a jersey in the Tour? Those who know their history might say Philippa York, who under her previous name of Robert Millar won the 1984 men's mountain classification. But they would be wrong.

Even discounting 1955-won by Brit Millie Robinson - in 1984 Louise Garbett won the maillot blanc for best young rider. Because the women's race finished earlier in the day than the men's, Garbett was the first person to win a Tour de France jersey for Great Britain.

The history of the women's Tour, culminating in its current iteration as the Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift, is long, complex and filled with both triumph and frustration. French women have raced bikes since the 19th century, when they would use pseudonyms to escape disapproval.

By the 1930s, newspapers advertised criterium races with 'hommes' and 'femmes' categories. In the late 1940s, more than 15 years after the first men's Tour, L'Intransigeant ran a story about a women's cycle group planning their own Tour de France in stages of "50 to 60 kilometres per day". ("How long would that take?" the writer asked.)

The first proper attempt at a 'Tour Féminin Cycliste' was in 1955. It was five days long and a mere 372km, with a white jersey for its leader rather than the traditional maillot jaune. Owing to insufficient coverage, the race lasted only one edition. Two years later, when UCI member states voted against introducing a women's World Championship, L'Équipe crowed that "common sense" had triumphed.

The peloton lines up at the start of the 1984 Tour de France Féminin

Louise Garbett was the first British rider to win a Tour de France jersey

Inequalities were a continued feature of women's bike racing into the 1980s and the Tour de France Féminin. In her book Pedal Power, Anna Hughes tells the story of its first winner, US rider Marianne Martin, who crossed the finish line "to ecstatic cheers," took her place on the podium alongside men's winner Laurent Fignon, and was awarded prize money less than a hundredth of his.

But there was also support. An upcoming film about the Féminin, Breakaway Femmes, includes a memorable clip from the 1980s of then-racer and eventual FDJ-Groupama team boss Marc Madiot telling French road race champion Jeannie Longo that he finds her "ugly". He also said he would watch women's cycling "the day they put on jerseys that are a little prettier, shorts a little prettier and shoes a little prettier".

Greenwood recalls riding the Tour shortly after Madiot's comments aired and spotting a homemade banner on a corner that read: "Marc Madiot is ...". The final word was unfamiliar to her - and even a French-speaking Canadian team-mate didn't recognise it. But the French riders were giggling. "We said, 'What is it? We don't understand.' Well, you can imagine. They started acting it out," Greenwood says. The moment was funny, but also meaningful: "It showed the French were on our side".

The last Tour de France Féminin was in 1989; the organisers said it was too expensive to continue. Other equivalents were attempted, including a 'Tour Cycliste Féminin,' which became the 'Grande Boucle Féminine Internationale' after the company that owned the rights to the men's Tour de France contested the name. "It was very frustrating," Hepple says. "It felt like it had gone backwards".

Kathryn Bertine is an ex-pro and activist who took up the fight for a women's Tour de France in 2009. She compiled a 22-page dossier which she sent to race organisers the Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO), outlining what she saw as not only a chance to do the right thing, but also an enormous commercial opportunity.

She got no reply. She formed an activist group, Le Tour Entier, with fellow pro cyclists Marianne Vos and Emma Pooley and the triathlete Chrissie Wellington. They secured a petition of almost 100,000 signatures - but also faced pushback from people who didn't believe women were capable of racing a Grand Tour, a response Bertine found "dumbfounding"

"This younger generation of girls will expect to get the same as the men."

Kathryn Bertine

It took five years of campaigning to initiate La Course, a one-day race which debuted in 2014 on the Champs Élysées. Her sense of achievement standing on the start line is, Bertine says, one of her "all-time podium of memories". But she wasn't done.

The event was overshadowed by weeks of men's racing, and riders such as Annemiek van Vleuten criticised the stages for being too easy. Others reported facilities issues; Lizzie Deignan said she couldn't find a women's toilet. The ASO, for their part, said it would be "impossible" to stage a full race alongside the men's.

But the campaign had velocity. In 2019, CW reported on the InternationElles, a group of women riding each stage of the Tour the day before the men to call attention to the lack of a women's edition. Finally, in June 2021, the ASO announced the Tour de France Femmes: "a new women's race" of eight stages with the same "codes, values and symbols" as the Tour de France, including a yellow jersey sponsored by LCL and a Queen of the Mountains jersey sponsored by E.Leclerc-just like the men's.

The first race, in 2022, started on the Champs Élysées the day the men's Tour finished there, encouraging spectators to watch both. Just as importantly, it was broadcast in 190 countries. After seeing coverage of previous races looking "like they'd been filmed with a phone," Hepple was thrilled to be able to watch the high-quality footage

Kasia Niewiadoma leads the peloton at the 2022 Tour de France Femmes

Bertine stresses her excitement while also calling for the Femmes to be a bigger, longer race - matching the appetite she sees for women's racing. She also wants equal prize money - Bertine has calculated that the Femmes riders earn 29% of their male counterparts' pay per day raced.

She believes there is more money to be made in general - she even approached the ASO, asking them to hire her in a role in which she would market the Tour to sponsors. "They said, 'we don't have that position.' I said, 'I know'".

It is also important for Bertine that the history of the race is more widely known. She runs an organisation for young professional riders called Homestretch, in which she encounters many women who are unaware of La Course, let alone the Féminin. For Hepple, young women taking the women's Tour for granted is a hopeful sign: "I think that's fantastic. This younger generation of girls will expect to get the same as the men".

Last month, sponsor Zwift released a report on the impact of the Tour de France Femmes. Their survey found 85% of respondents now consider professional cycling "a viable profession for women to aspire to".

Veterans return

Greenwood speaks quietly when she tells the story of what it was like, those 40 years ago, when the bunch spotted the Eiffel Tower after three weeks on the road. "There was this moment where we all froze in time". She isn't sure if a three-week women's race will happen again: "I really don't know". Bertine points out that if the Femmes were to add a stage a year, they would reach parity with the men's Tour in 2040.

Yet fan appetite is strong and growing across women's sports. Last month, 15 million people tuned in to watch the Lionesses win the Euros for England. On the final stage of this year's Femmes, crowds lined the switchbacks of the Portes du Soleil ringing bells borrowed from the local cows for Pauline Ferrand-Prévot, who had grown up wishing she was a boy so she could win the Tour de France.

Her dream realised, she is France's first Tour winner since Jeannie Longo in 1989. Standing on a concrete barrier in the last 500m of the Col du Corbier, I watched the world-famous names flash by on riders' backs: Vollering, van der Breggen and Vos, cheered on by fans packing the roadside. But even more indicative of the Femmes' popularity was the atmosphere in local bars the day before, where men screamed 'allez' at the television as Ferrand-Prévot rode her way into yellow, alongside a peak audience of 5.4 million.

Pauline Ferrand-Prevot finally wins the yellow jersey for France

Last summer, Bertine joined a trip to watch the Tour de France Femmes with some of the 1980s racers who feature in Breakaway Femmes. The day of the 2024 time trial stands out in her memory because 'the originals and the friends,' as they called themselves, rode to the start pen before the race. As the older women wandered around, teams warmed up on rollers ready for the race ahead. Most of them were unaware, Bertine says, that the first generation of the women's Tour were watching them

1955: Sports journalist Jean Leulliot creates the first Tour equivalent for women riders, with a peloton of 41. It lasts one edition.

1984: Marianne Martin of the United States wins the first Tour de France Féminin over 18 stages.

1989: Jeannie Longo wins her third Tour de France Féminin in the final year of the race.

1990: A Tour de la C.E.E. féminin is launched. It lasts until 1993 with races of between nine and 12 stages.

1992: Journalist Pierre Boué launches the Tour Cycliste Féminin. Jeannie Longo podiums in three editions.

1998: The organisers of the men's Tour dispute the name. The race is renamed the Grand Boucle Féminine Internationale.

2009: The last Grand Boucle, won by Emma Pooley.

2014: La Course debuts as a one-stage race. Riders such as Annemiek van Vleuten argue for harder, more ambitious stages.

2022: The first edition of the Tour de France Femmes debuts with a field of 132 riders. Van Vleuten wins the general classification.

2025: 154 riders line up for the Tour de France Femmes. The winner's prize money is €50,000, a tenth of the men's equivalent.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.