Investigation: What would it take to beat a pro?

Just how much fitter would you have to get to keep pace with a full-time pro? CW fitness editor David Bradford lays his data on the line and dares to compare

(Daniel Gould)

Three-hundred and 39 watts for one hour and 51 minutes. That was the extraordinary effort with which Vincenzo Nibali won Stage 20 - cut short to 59km, owing to apocalyptic weather - at this year’s Tour de France.

That equated to a normalised average power of 353 watts (the output sustainable if the effort had been completely consistent); and let’s not forget, Nibali is a puny climber who weighs just 65kg, meaning his average power-to-weight for the entire stage was 5.4W/kg - pushed out by legs already battered by three weeks of racing. To anyone who knows what 350W feels like on a bike, those stats provoke an irresistible question: what on earth would it take for a mere mortal like me to reach that level of performance?

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

I’m exactly the same height and weight and just 2.5 years older than Nibali, but the similarities end there. Though I’ve ridden bikes all my life, I’ve never raced or followed a specific training programme; my endurance background is as a runner - I ran a few half-decent marathons before long-term injury niggles took hold in my early 30s. Having never even flirted with my limits on the bike, I was intrigued to know how I would stack up on the performance spectrum which spans from totally untrained to world-class. How big was the gulf between me - a has-been club runner turned recreational cyclist - and a top-flight rider like Nibali? There was only one (painful) way to find out.

Before booking in for physiological testing, I decided to recruit a test companion, someone for whom the benchmarks really mattered - a young rider who was taking our headline question seriously and striving to reach pro standard. Nineteen-year-old Callum McQueen fitted the bill perfectly.

He’d emailed CW a few weeks earlier to outline his ambitious plan: having saved up some cash from working in a bike shop, he’d “taken the plunge” last year and quit his job to go full-time on the bike, training up to 25 hours per week, with the aim of securing a pro contract. For Callum, the question was less the meandering hypothetical ‘What would it take to be a pro?’, more a statement of intent, ‘What will it take for me?’

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

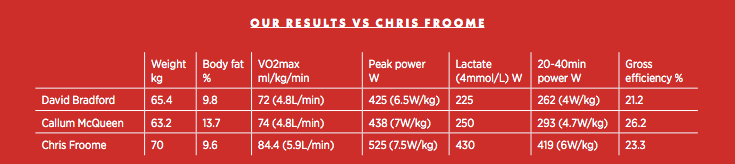

Our pro rider comparison data would be provided not by Nibali but an even more phenomenal talent: Chris Froome. Tested at the height of his powers in 2015, Froome shared the results with Esquire, partly as an attempt to quash accusations of foul play following the second of his four Tour de France wins. Whether performance data can ever prove (or disprove) doping is a question for another time; for now, it was time to find out just how great a fitness leap Callum and I would have to make to get anywhere near to keeping up with a GC grandmaster.

One watt at a time...

Our testing takes place at the University of Kent, in Gillingham, where vastly experienced physiologist Dr Mark Burnley and researcher Hannah Sangan have kindly agreed to take us through the exact same protocol that Froome underwent in 2015. Our first job upon arrival, before the torture can begin, is to sign a health disclaimer and get weighed and measured. I’m relieved to discover that my weight has barely changed from my marathon running days; Callum, who is slightly taller at 6ft, weighs just 63kg, a full 2kg less than me — damn, I’m falling behind before a pedal has been turned.

The two-part fitness test, using a Cyclus ergometry system with carefully calibrated gas analysis, will precisely measure our lactate threshold and maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max): the two key metrics for endurance athletes. I’m first up and told to spin at a steady cadence of 80rpm as the resistance is increased by 25W every three minutes and a finger-prick blood sample taken. So far, so simple. Six stages in, the effort still feeling manageable, Burnley tells me that’s enough; he has all the data he needs.

After a 20-minute rest, it’s time for the main event: my VO2 max test. Unlike part one, this is a ramp test, meaning the power will increase by one watt every two seconds until I literally can’t go on. It’s a strange sensation: the resistance rises so incrementally that, like a frog in warming water, I’m barely aware of the impending peril. Everything seems fine until the 350W mark, when I’m forced to face the reality that for me - unlike for Nibali - this is seriously hard and imminently unsustainable. Four-hundred watts becomes my do-or-die target, and somehow I get there - though by this point I’m labouring frantically, rocking around all over the bike and panting like a pursued animal. The biggest surprise is just how long I’m able to sustain this end-of-tether intensity - it’s another 40 seconds of gasping, howling hell before, at 425W, I slump to a sweat-drenched halt, definitively maxed-out.

Callum’s test proceeds, on the face of it, in remarkably similar fashion, only this time I’m watching (and yelling encouragement). He hangs on for a bit longer in both parts, no surprise, but the margin of difference is smaller than we’d all expected — and I begin to wonder whether the gap separating a modestly trained cyclist like me from an extremely well-trained athlete like him might just be bridgeable. “I could have been a contender!” I dare to dream, still drunk on endorphins - before having to accept it’s time for a cold shower.

VO2 max v lactate threshold

The next day I receive an email from Burnley laying plain our results and their implications. First up is VO2 max, the maximum rate of oxygen consumption, or what Burnley refers to as “the size of the engine”. My and Callum’s results are 72 and 74ml/kg/min respectively, placing us both in the performance band categorised as ‘excellent/domestic pro’. I’m delighted, and it’s encouraging for Callum too, though there’s no ignoring that his max uptake is a full 10 short of Froome’s mammoth 84ml/kg/min. Does this represent a serious limitation?

“Not necessarily,” says Burnley. “At very elite levels, VO2 max is not a very useful way of distinguishing between athletes; its relationship to performance is complex — other factors are at play.”

The trainability of VO2 max varies widely between individuals, though for someone very well-trained like Callum, the physiology determining his max oxygen uptake — principally, the capacity and pumping power of his heart — is probably close to its full potential already. The greater room for improvement lies elsewhere: “This is why we tend to be more interested in things like lactate threshold and economy,” says Burnley, “because they are far more trainable, no matter how fit you are.”

Lactate threshold is determined by biochemical processes, with no clear upper limit; training continues to increase the number of mitochondria (“powerhouses of the cell”) as well as the blood capillaries supplying fuel and oxygen, while also adapting fast-twitch and intermediate muscle fibres to make them work more aerobically.

Watts the difference?

On this front, Callum’s lactate threshold, at 250W, is one ‘stage’ higher than mine, giving him an estimated sustained power (similar to FTP) of 293W (4.7W/kg) and casting my 262W (4W/kg) into the shade. But never mind my shattered dreams, what would it take for him to hold the wheel of a top-level pro? GC stars like Froome and Nibali are able to sustain close to six watts per kilo for prolonged periods of racing. To get to that level, Callum would need to improve his sustained power by at least one watt for every kilo of bodyweight - a bridge too far?

“That’s the million dollar question,” says Burnley. “Partly it’s genetically predetermined - Froome’s baseline lactate threshold, even if he never trained again, would still be north of 300 watts - but all of us can target the factors that shift lactate threshold, and it’s possible to keep improving over not just months but years.”

But is a 60-watt gain plausible? “It’s hard to say in Callum’s case. At 19, he’s close to physiological maturity, but parameters like lactate threshold can continue to improve throughout an athlete’s career, provided they keep training effectively. Over the next five years, a 50, 60, perhaps even 70-watt increment isn’t out of the question.”

There is a final extra sweetener for Callum. The third pillar in the holy trinity of performance is efficiency - essentially the proportion of energy used that is converted into pedalling power. Callum’s mean efficiency is 26.2 per cent, which is not just good but almost off the scale.

“That’s as high as I’ve ever measured,” confirms Burnley. “Callum is extremely efficient, which means, compared to less efficient riders, he uses less fuel to produce the same power. In a long stage race, for example, he’s going to last longer before he hits the wall - he’ll spend less time suffering.”

To illustrate the point, Burnley contrasts with my bog-standard efficiency: with each equivalent lungful of oxygen, Callum generates significantly more power. “Callum’s absolute VO2 max of 4.78L/min was identical to yours, but for the same effort he was producing 13 watts more than you.”

Without remorse, Burnley despatches my competitive prospects one by one. “In a long race, Callum would outlast you because he is more efficient. In a time trial, he would win because his threshold is 25 watts higher than yours, and he would out-climb you because his power-to-weight ratio is significantly higher.”

Thankfully, he spares me the humiliation of speculating on the time cost of my lack of bike-handling skills - one of many additional factors that can prove decisive. It seems fitness alone isn’t nearly enough.

How good are the pros? The numbers compared...

Nature and nurture

Top-level pros are far more than just big engines with powerful pistons. To make it to the top, you need the right genetics, a lot of good luck, a conducive training environment, resilience to injury, psychological aptitude, expert coaching, financial support, and all the rest. For me, getting even close to the performance level of an aspiring pro like Callum is out of the question. For Callum, all we can say for certain is that his physiology is promising and his determination palpable; exactly how far he gets rests on the myriad makers and breakers, many of them uncontrollable, otherwise known as the hands of the gods.

Could you pass the UCI's fitness test?

Academy Coach's View: A big engine isn't enough

CW asks British Cycling Academy coach Ben Greenwood what it takes to make it to the top of the sport

“On paper, I could have got a top 10 in a Grand Tour,” says Ben Greenwood, recalling his physiological stats as a young racer in the late-Nineties. His VO2 max was a top-notch 85ml/kg/min, and he could sustain the magic six watts per kilo - yet he still didn’t make his mark on the world stage. “I didn’t have enough knowledge, and got injured. It’s a classic case of, ‘if only I’d known then what I know now’.”

It is knowledge, according to Greenwood, that allows a physically gifted rider to reach their full potential - and he sees this happening every day. “Riders are learning more at a younger age. With modern technology, they can learn faster; they don’t need a teacher or coach, just a smartphone.” Coaching has therefore become less didactic and more collaborative. “It used to be that we [coaches] had all the knowledge and told riders how to be better.

Now it’s more of a case of us asking them how they are going to improve, letting them reflect - and the reflections you get from 15-year-olds now are incredible.” The differences separating riders at the sharp end of the development system are vanishingly small - everyone is talented.

“They all have good power,” says Greenwood, “but the reality is, they don’t all make it to the next level. Smaller things become significant. For example, if we power-tested Tom Pidcock, he might not record the highest, but he is the best racer and the best bunch rider - the amount of energy he saves by being technically better more than makes up for any shortfall.”

Only very occasionally does a rider come along who has such exceptional fitness that they’re able to simply outpower everyone else. “A rider like Remco Evenepoel, winning WorldTour races at 18, is able to rely purely on his engine,” says Greenwood, “but for most upcoming riders, if they only focus on physicality alone, they’re not going to make it.”

Whether it’s Evenepoel winning San Sebastian, Egan Bernal claiming the Tour title as an under-23 or Tadej Pogačar leading the Vuelta aged 20, champions are getting younger. And that means learning curves are getting ever steeper — only possible in countries with nurturing yet fiercely competitive development environments.

“When I was racing, David Millar and Charly Wegelius were the only two British pros,” remembers Greenwood. “Now we have over 20 WorldTour British pros. Young kids today almost expect to become the next big champion.”

The UK is now producing more talented riders than its development system can accommodate. “There are too many good riders for us to take now,” says Greenwood. “That’s been the biggest change. The junior Academy has nine spaces for next year — but there will be many more than nine riders with WorldTour potential.”

He urges young riders not to be put off by the toughness of the competition. “The kids getting top-10s in national junior races should not be disheartened - they need to keep going because they could still end up making it all the way."

The aspiring pro: ‘I’m young, so let’s give this my best shot’

CW lab test volunteer Callum McQueen, 19, has gone full-time and is shooting for the stars.

Like so many of the latest crop of upcoming British racers, Callum McQueen was inspired by watching TV coverage of the London 2012 Olympics. “We were on holiday at the time,” he remembers. “When we got home [to Bramley, Hampshire], I saved up and bought a road bike, then joined the local club, Palmer Park Velo, and started learning the basics.”

It wasn’t until his mid-teens, however, that he began training more seriously, working with the club coach. Two years of steady progress later, he decided to make cycling his life’s main focus.

“As the 2018 season ended, I was really enjoying it and feeling keener than ever to get results. I thought to myself, ‘While I’m young, let’s give this a go’. I took everything from the level it was and raised it five notches.”

Fully committed now, there was no turning back; he quit his job at a local bike shop to become a full-time rider.

“From doing 10 or 11 hours a week and squeezing in training before work, I’m now doing 15-25 hours a week, following a specific plan under the guidance of [Canyon dhb coach] Tim Elverson.”

It’s not the typical lifestyle for a 19-year-old lad — all that riding must curtail nights out drinking and socialising?

“Oh yeah,” says Callum, “I see on social media people I know from school going out all the time. I don’t go out because 1. the cost, and 2. I know it would make the next day’s training even harder. It’s about weighing up what you want against what you need.”

Wait a minute — you literally never go out for a beer?

“Honestly, I don’t think I ever have,” he pauses. “Oh, I went to a wedding once.”

The clean living will prove worth it if he can attract the attention of a pro team. Callum knows that the selection process is very results-driven and he needs to win races to get noticed. Cycling is a particularly unbending employment market — especially with at least two domestic teams pulling the plug at the end of this year. What motivates him to keep working hard and aiming high?

“Sometimes it’s just watching races on the telly or riding with other people. My parents are motivational too — I always want to make them proud; they’ve given me so much. More than anything, though, it’s that feeling when you win a race and you know that all the effort has paid off.”

So what’s the ultimate goal?

“WorldTour would be awesome,” says Callum with firm resolve, “but for now it’s just ticking off goals, keeping things going, staying positive.”

What makes for success? Body composition and biomarkers

It’s a misconception that pro cyclists are super-light and ultra-skinny. As recently highlighted on science4performance. com, the average height and weight of a pro rider is around 5ft 11in and 68kg — equating to a BMI of 21, towards the middle of the healthy range. Of course, highly trained cyclists have more leg muscle and less body fat than most ‘normal’ people, but with the emphasis on the former — developing power (and therefore muscle, which is heavy) takes precedence over shedding fat (they’re lean already).

How did we compare? My body fat percentage (tested three years ago at the same weight as now) was just under 10 per cent — the same as Froome’s in his winter 2015 test. Callum, who at 19 is likely still developing muscularity, measured slightly higher, at 13.7 per cent, when DXAscanned at the University of Reading last week. Both of us are within athlete range, with limited scope for fat loss.

What about our blood? Doesn’t an aspiring pro need exceptional levels of minerals and hormones coursing through their arteries? To find out, Callum had his blood tested by biomarker specialist Forth Edge (forthedge.co.uk) and analysed by sports endocrinologist Dr Nicky Keay.

“For an endurance athlete, my eye always goes straight to haemoglobin — you need blood that’s good at carrying oxygen,” says Keay. “Callum’s is 15.6 [grams per decilitre], which is pretty darn good.” (For comparison, Froome’s was 14.5g/dL.)

Callum’s haematocrit — the ratio of the volume of red blood cells (RBCs) to the total volume of blood — is also good, at 46 per cent, though Keay notices his urea is raised, meaning dehydration might be a factor in the high concentration of RBCs.

According to Keay, Callum’s healthy cortisol and testosterone levels provide solid reassurance that he is not overtraining. Similarly, his thyroid hormones indicate that his metabolism is working as it should, with plentiful energy on tap. Her only quibble is his vitamin D level of 55ng/ml. “Fifty-five is too low for an athlete — you need to be at 90 or above for optimum bone health, muscle strength, and immunity. Get your hands on some Informed Sport vitamin D supplements — a cheap, easy performance gain.”

Does an aspiring pro need to hit specific, elite-level blood biomarkers?

“No, fundamentally we all share the same fairly narrow physiological parameters,” says Keay, “but blood tests allow you to train more like a pro in terms of paying attention to the details, making sure you’re fuelling and recovering effectively. Callum’s results suggest he’s doing everything right.”

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

David Bradford is senior editor of Cycling Weekly's print edition, and has been writing and editing professionally for 20 years. His work has appeared in national newspapers and magazines including the Independent, the Guardian, the Times, the Irish Times, Vice.com and Runner’s World. Alongside his love of cycling, David is a long-distance runner with a marathon personal best of 2hr 28min. Diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in 2006, he also writes personal essays exploring sight loss, place, nature and social history. His essay 'Undertow' was published in the anthology Going to Ground (Little Toller, 2024). Follow on Bluesky: dbfreelance.co.uk