La Madone: Tour contenders' favourite testing ground

We investigate why riders are still drawn to the southern French climb made famous by cycling’s most controversial figure

Photo: Chris Catchpole

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A fit amateur can do it in less than 45 minutes. A professional rider is looking for something under 36. Generally the closer they can get to the half-hour mark, the better.

However, there comes a point where riders are reluctant to shout about their best time. There is something taboo, a secret shame, about riding quickly up the Col de la Madone.

It’s something acknowledged by Chris Froome in his 2013 autobiography The Climb, when he describes tackling the Madone with his team-mate Richie Porte just six days ahead of the 2013 Tour de France in a time of 30-09, pumping out a 459-watt average.

“It’s a strange feeling we have after doing it. We feel slightly guilty and a bit sheepish,” he wrote. “I turn to Richie: ‘We can’t tell people about this.’ We don’t want to go there.”

The Madone is one of the most famous — and infamous — climbs in professional cycling. Yet it isn’t known for the scenery, its maximum altitude, steepness or number of hairpin bends. It has never featured in the Tour de France.

The Col de la Madone is famous because it was the climb chosen by Lance Armstrong to test his form ahead of the Tour de France.

Miracle mountain

The Madone became an integral part of the Armstrong myth, almost like a holy site where miracles were supposed to have taken place. When the Texan lived in Nice during the early years of his comeback after cancer he would use his time on the climb as an indication of form. The Armstrong of early 1998 was stopping the clock at 36 minutes. By June 1999 his time was down to 30-47.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Of course we now know that the climb also provided his doctor, Michele Ferrari, with crucial information on blood levels, power data and physiological limits in order to tailor his programme of training and performance-enhancing drugs.

>>> Review: Lance Armstrong biopic ‘The Program’ (video)

Armstrong’s team-mate Tyler Hamilton revealed in The Secret Race that he recorded his Madone time in his diary along with weight, heart rate, power and haematocrit. In a matter of weeks between March and June 2000, he took 3-31 off his best time. Miracles indeed.

“If I went to the Madone two weeks before the Tour and went as hard as I could, I knew if I was going to win the Tour or not,” Armstrong explained at the peak of his pomp.

“I mean, it always told me the right things. But had I gone and been a minute and a half slower, I would have known that I wasn’t ready.”

The Madone even lent its name to Armstrong’s bike. Before 2003, the best Trek that money could buy was an OCLV 5500, a good bike but hardly an evocative name to get the heart pumping.

>>> The top 10 game-changing road bikes

In 2003 the American brand introduced the Madone. It was slick, it was exotic, it was Euro, and it sold by the bucket load. Madone is still the name for the company’s top-level aero frame, and the name is in the DNA of its other machines too.

It appears Trek brand executives simply chucked the Scrabble letters back in the bag and pulled them out again in a different order. Emonda is Trek’s lightweight climbing bike and Domane its machine for sportives and cobbles.

Unfairly maligned

It’s a shame that the Madone has such a toxic past because like a lingering bad smell it can get in the way of just how pretty this climb actually is.

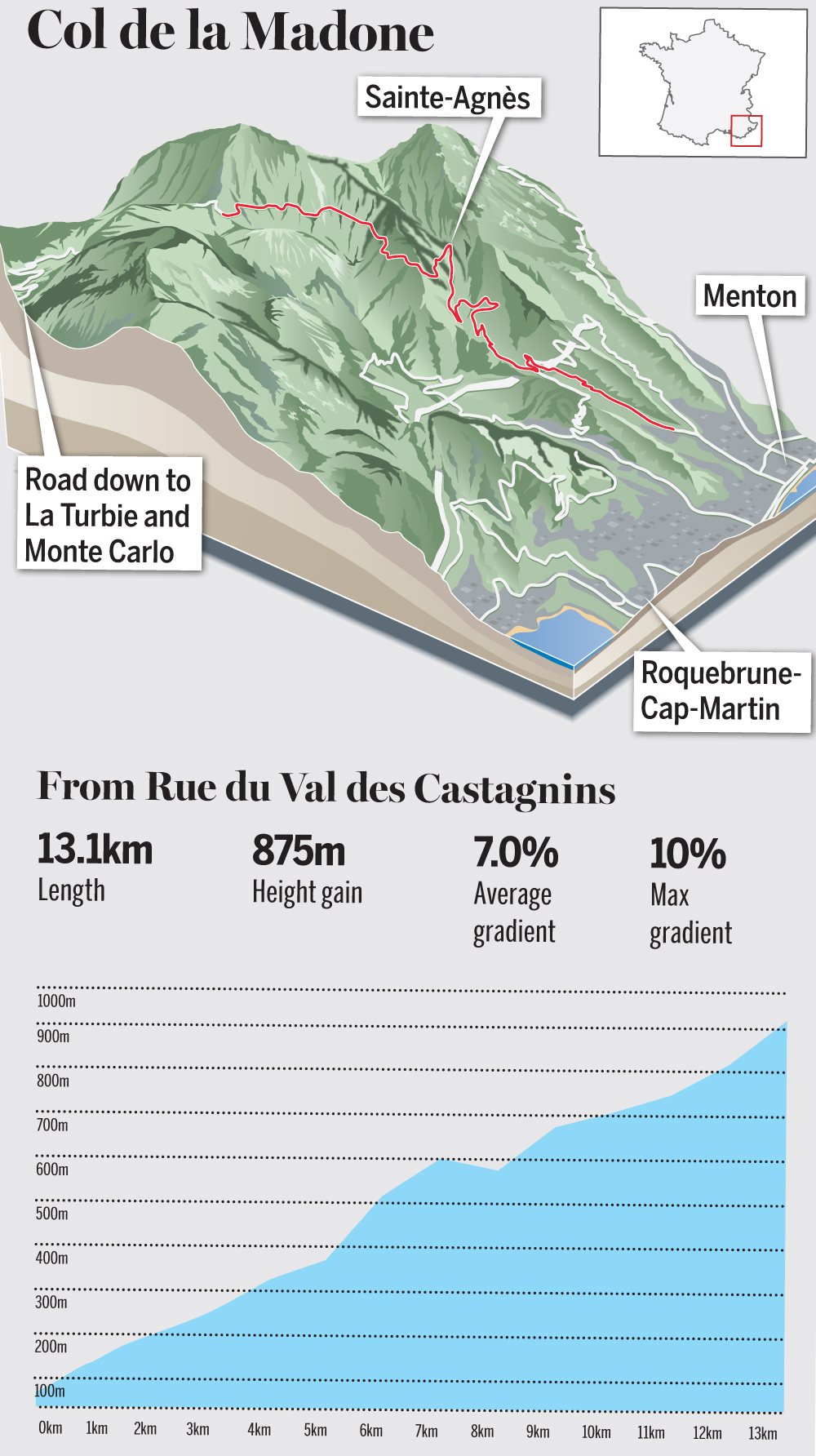

Over its 13.1km, the road — named in full the Col de la Madone de Gorbio — heads out of the town of Menton, the final French town before Italy, and the fumy hustle and bustle of the French Riviera.

Get up any climb

It’s almost more of a back road; the carriageway is narrow and the surface far from the ideal, smooth blacktop that you’d expect for a climb of such renown. Switching back in a series of three hairpins underneath the A8 motorway viaduct, it winds its way past the turning to the medieval village of Sainte-Agnès before continuing up and west into the quiet hills. Once over the summit at 925m, the road descends immediately, eventually winding back down to La Turbie and

Monte Carlo.

Riders on the Côte d’Azur have been cycling up and down it for years but it was Tony Rominger, who won the 1995 Giro d’Italia and three editions of the Vuelta a España, who first went there specifically to test himself.

The climb was attractive because it simulated a 30-minute effort right on his doorstep and its south-facing slopes remained warmer in winter. Current pros use it for smaller efforts too.

Nowadays Froome and Porte are the biggest proponents of the climb, and the Tasmanian holds the current record. Most pros living nearby, including Tom Boonen, Philippe Gilbert and many Sky riders, will have ridden it in training, along with the likes of Formula One racing drivers Jenson Button and Mark Webber. Although the road is quiet and has spectacular views right down to the coast, it’s not always particularly enjoyable.

>>> 17 of the best international sportives to ride in 2016

“It’s horrible, there’s no constant gradient, and it’s steep,” says Adam Blythe, who swapped Sheffield for the Monégasque sunshine when he turned pro with Omega Pharma-Lotto. “You just can’t get into a rhythm on it.”

For amateurs the Madone offers an opportunity to measure themselves against the best in the world, as enough of the pros’ times have been revealed in the press or on Strava to make a comparison.

More than that though, there’s a dark attraction to this sunlit climb. In the words of Froome and his autobiographical ghostwriter David Walsh, the Madone “is a fallen woman. Her name is tainted by the sins of her former lover”.

Whether it’s to enjoy the scenery, see how you stack up against the pros, or find out if you’re fit enough to win the Tour, the Col de la Madone is still drawing cyclists in.

How to do it

When to go

The Col de la Madone usually remains open all year round. However, even the French Riviera gets cold in winter, particularly at the height of 925m at the summit. July and August are busy months in Menton — spring, early summer and early autumn are the best times of the year to ride.

How to get there

Fly to Nice (40km by car from the Madone) from a range of UK airports. From the seafront at Menton, ride north on the Avenue Cochrane before following the D22 left onto the Route de Sainte-Agnès.

While you’re there

The quaint village of Sainte-Agnès is a fine place to enjoy a mid-ride coffee, and the area around Menton is jam-packed with quiet, scenic climbs. The nearby Col de la Madone de Utelle is a scenic dead-end climb while the Col de Braus offers a set of perfect hairpins. For a sterner test, head north to the Col de Turini.

The Col d’Eze, the uphill TT finale to Paris-Nice, is situated south-west along the coast while the other direction takes you across the border into Italy to San Remo and the Poggio.

Where to start?

One of the biggest factors determining a rider’s time up the Col de la Madone is nothing to do with power-to-weight ratio or climbing wheels; it’s a matter of where to start the stopwatch.

>>> I cheated on Strava and got a really amazing KOM

The Strava segment for the climb begins at the widely accepted start point: the Intermarché supermarket to the left (heading uphill) on the Rue du Val des Castagnins on the edge of Menton.

However, Froome describes his start line as the bus stop just past the first bend in the hamlet of Les Castagnins, around 600m up the road.

A more famous French climb

What’s in a time?

When Richie Porte revealed to Cycling Weekly earlier this year that he had set a new record time up the Col de la Madone of 29-40 in June 2014, his critics rounded on him and his training partner Chris Froome.

His time, a minute quicker than Lance Armstrong’s reported best, was construed as circumstantial evidence that he too was doping. The same questions came back to haunt Froome at the 2015 Tour as critics called for him to release his power data from key climbs.

>>> What can we learn from Chris Froome’s power data?

What can be inferred from a time up the Col de la Madone? With the variables of start locations (see additional boxout), weather, traffic, equipment and relative fitness: both everything and nothing. The only thing it truly proves is the climate of suspicion and uncertainty that still dogs cycling to this day.

Richard Abraham is an award-winning writer, based in New Zealand. He has reported from major sporting events including the Tour de France and Olympic Games, and is also a part-time travel guide who has delivered luxury cycle tours and events across Europe. In 2019 he was awarded Writer of the Year at the PPA Awards.