Riding the Mortirolo: Cycling’s toughest climb

The Mortirolo’s name derives from the Italian for ‘dead’ and its 32 torturous turns certainly make you long for the end.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Never again.

In the lucky position I find myself, there aren’t too many moments when I travel overseas with my bike and wish to be elsewhere.

However, having stopped for the umpteenth time in sheer exhaustion three-quarters of the way up the seemingly never-ending small track in northern Italy that is the Mortirolo, this was one of them.

Rolling into the town of Mazzo di Valtellina an hour before wasn’t exactly comparable to what Le Bourg d’Oisans is to Alpe d’Huez.

With a population of just over 1,000, the commune has an almost derelict feel to it.

>>> Alpe d'Huez: Classic climbs of the Tour de France

A quick lap around the small but quaint town suggests that 1,000 may be a generous estimate — either that or it’s a warning that those who have passed through to ride the Mortirolo never return.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

As I pass the signs for the climb pointing eastwards to what looks like a forest wall, I wonder if this will be the last time I pass through Mazzo.

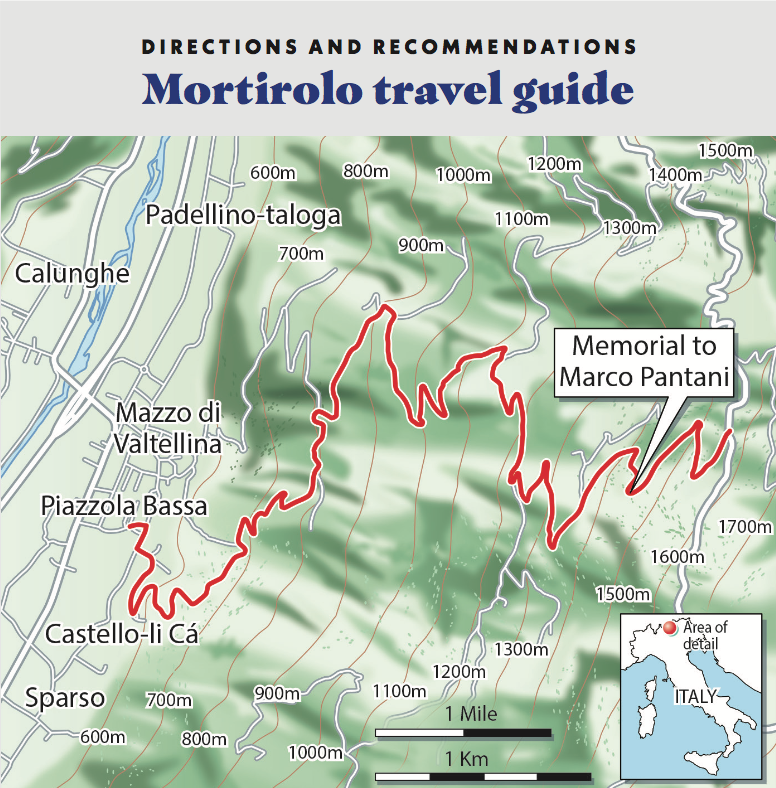

The climb nicknamed Salita de Pirata or ‘Pirate’s Ascent’ in honour of Marco Pantani, is a tricky climb to find among the narrow streets of Mazzo.

As I ride up Via delle Fontane I pass the Mortirolo sign, before the road gently rises upwards and left onto Via Valle where the harsh gradients really begin.

This is the last piece of navigation I’ll have to worry about until joining up with the Strada dello Mortirolo 2.5 kilometres up the road, as I begin my slow-motion ascent to the summit.

Despite being well aware from researching the Mortirolo before I arrived in Italy that this wasn’t just an odd 14 per cent pitch in the gradient, but rather the general theme of the next 10 kilometres, nothing could prepare me for the seemingly endless grind of double-digit gradients that lay ahead.

>>> Riding to the sky above: Taking on the Passo dello Stelvio

The silence of the valley continues up the climb, with just a few houses dotted either side. Shortly I pass the last smattering of buildings before the top.

Upon reaching the first of the 32 turns or tornantes, which count down to turn number one at the top of the climb, you assume it will level out at some point.

As I gaze down the valley at Mazzo — where my heart rate wasn’t going through the roof — I suddenly realise just how far I have climbed in a short amount of time.

This thought quickly disappears as the road contorts its way up through the woods with its unrelenting gradient and I realise that this pace, cadence and effort is unsustainable. Which leads me on to the first lesson the Mortirolo taught me.

Unprepared and overgeared

Prior to heading out to northern Italy, my Scott Addict was fitted with a 52x36 on the front, with a 28t cassette on the back.

Naively I thought this combination would be low enough for me to blag my way up after a half-decent summer of riding but the Mortirolo had other ideas.

It has no mercy for those who don’t come equipped with a compact chainset and a 30-tooth cassette.

If you have the capability to fit a dinner plate on the back then you won’t regret it — I put my chain into the 28-tooth sprocket and stayed in it.

When Alberto Contador — one of the greatest climbers in recent history — made his Giro-winning attack up the same climb in 2015, he had a 34x30, showcasing how naive my set-up truly was.

Officially the Mortirolo has 32 corners, but it’s twisty and the straights never stretch on longer than 150 metres, meaning there are many bends that aren’t marked up.

This adds a level of mental torture on top of the physical pain and as my oxygen-deprived brain tries to figure out how far I’ve got, I round the next bend and find it’s not a proper bend at all.

>>> The hidden motor in your head: How mind training can make you ride faster

As I gain in altitude I theorise that this confusion is the product of some sadistic local who kindly put up signs on the first four bends only to start skipping turns after that.

I picture them cackling like a Bond villain as they drive their 1981 Fiat Fiorino up the climb: “This’ll mess with their heads!”

Turn, turn, turn...

I’m well aware that I am not selling the Mortirolo as a pleasant climbing experience, but the uniqueness of its unrelenting ascent makes it an unforgettable ride for any cyclist up for the challenge.

What is most singular about the Mortirolo is that, despite being one of the sport's iconic climbs, the nature of its narrow claustrophobic singletrack road from bottom to top is rare in road racing.

The trees that line the road from the base to the summit are my only company on my slow-motion ascent.

The one respite from the constant blind corners jinking their way skywards is the section of road that bends around the San Matteo church about four kilometres in.

Unfortunately, this is where the breaking point of the climb arrives, with an eye-watering 19 per cent ramp.

It is also where I came to the realisation that if ever there was a climb I was desperate to get to the top of, just so I could say I had done it and never return, the Mortirolo was that climb. It’s that, or curl up in the overgrowth at the side of the road and let the mountain consume me.

The alpine woods, which are punctuated every few hundred metres with a gap in the treeline down towards the valley, are more suffocating than soothing.

The feeling of loneliness and isolation is ever present. The sight of just two other cyclists on the entire ascent reinforce the fact it is you and you alone that is going to get you to the top.

As I reach another cluster of bends, I’m reminded that the traditional use of hairpins to level out the gradient for cars to more easily make it to the summit seems to have been ignored by the Mortirolo’s road designer — perhaps that same sadist who put up the signs.

It is steep on the way into the bend, steep on the way round the bend and even steeper when you leave the bend.

>>> Marco Pantani - The highs and lows of a roller coaster career

If the enticement to stop does become too much, turn 11 seems as good a place as any to do so and pay homage at the memorial dedicated to the late Marco Pantani.

‘Il Pirata’ made his name on the Mortirolo in 1994 when he rode it in 42.40. It was the fastest ascent at the time but has been bettered twice since: in 1996 by Ivan Gotti and Roberto Heras and then in 1999 by Gilberto Simoni.

Pantani would have been able to make 2.5 ascents in the time it takes me to reach the summit; with his time in mind I continue to chug onwards and upwards.

At the right-hand turn of bend eight is the junction that the Giro d’Italia peloton descended during stage 16 of 2017’s race down towards Grosio, rather than use the far sketchier descent I’ve just climbed.

This was just the second time the Giro has gone up the kinder Edolo side, compared to the 10 occasions the path I’m crawling up has featured in the race.

The mountain has featured 13 times in total since its first inclusion in 1990, an average just shy of every other year.

Busted flourish

Thankfully this straight slog does drop the gradient to a much more reasonable 10 per cent, which by this point is almost unnoticeable as my mental and physical state doesn’t even realise what part of the climb I’m on now, let alone the gradient.

Despite another straight grind after the Grosio turn-off, the final corners come with relative regularity compared to the 25 that have painstakingly come before.

Thankfully the switchbacks are flattened out, raising my cadence above 60rpm, and are combined with much ‘nicer’ nine per cent inclines, with the treeline opening up from the dense woodland to a much less oppressive and open sight of the Rifugio Antonioli cafe.

I haven’t needed much of an excuse to stop and relax on the way up so far, but being so close I stand on the pedals for the final time and try and end with a flourish.

A flourish it is not — I flounder past the Instagram spot of the Mortirolo summit sign with very little fanfare.

As I chug to a standstill by our photographer Chris’s hire car, stop my bike computer (which actually auto paused on a few occasions — I’m blaming the lack of signal under the trees rather then the fact that I had almost ground to a standstill) and slump down onto the ground.

>>> Tips for effective rest and recovery after cycling

Lying down on the grass with my legs up against the open car boot, I revel in the realisation that I don’t have to turn the pedals again today.

Like most cyclists, I know deep down that in all likelihood the memories of the pain and the sight of the road disappearing skywards will subside.

My only thought on the plane journey back home is just how epic the Mortirolo is as a test of physical and mental strength, and that in all likelihood I’ll find myself back in this secluded part of Italy to try and do myself justice on this almighty brute of a climb.

The Cima Pantani

Established in 2004 after the death of Marco Pantani, the Cima Pantani is similar to the Cima Coppi that is assigned to the highest point of the Giro d’Italia each year.

However, the Cima Pantani is the prize to be the firrst over the climb that holds the most connection with the man in that year’s route.

It has been assigned to the Mortirolo five times since its inception in 2004 — more frequently than any other climb.

Cima Pantani winners on the Mortirolo

2004 Raffaele Illiano

2006 Ivan Basso

2008 Antonio Colom

2010 Michele Scarponi

2012 Thomas De Gendt

Two routes compared - Mortirolo

Mazzo Side

Distance: 11 km

Average gradient: 11.3 %

Elevation start: 552m

Elevation end: 1,852m

Elevation gain: 1,300m

Edolo side

Distance: 17.2 km

Average gradient: 6.7%

Elevation start: 699m

Elevation end: 1,852m

Elevation gain: 1,153m

How to get there

The nearest major airport to Mazzo is Milan, with both Malpensa and Linate airports running ights direct from the UK. However, a 3.5-hour drive is then needed to get to the base of the Mortirolo or the region where you’ll ideally like to stay.

Where to stay

The town of Mazzo is very quiet and the Mortirolo is one of a kind in terms of climbs in the direct vicinity. Bormio is a 30km ride north on the SP27 which is a bike-friendly road that runs next to the SS38 dual carriageway, so a rst choice for access if you do make Bormio your base.

>>> How to pack your bike for travelling

Bike shop

Cube Valtellina is the closest bike shop to the base of the Mortirolo, just 2.5km south of Mazzo. But be aware that it is closed on Mondays and Sundays and closes for lunch (this is Italy) so be wary if you are looking to x any untimely punctures.

Cafe stop

Rifugio Antonioli brings welcome respite at bend four just before the summit of the Mortirolo. It may be tempting to duck in and grab some food and drink but with just three short bends ahead it’s probably best to push on to the top and then head back down for a rest.

Paul Knott is a fitness and features writer, who has also presented Cycling Weekly videos as well as contributing to the print magazine as well as online articles. In 2020 he published his first book, The Official Tour de France Road Cycling Training Guide (Welbeck), a guide designed to help readers improve their cycling performance via cherrypicking from the strategies adopted by the pros.