The Koppenberg and the defining cobbles, bergs and climbs of the Belgian Classics

Throughout the history of the Classics, it's the cobbled roads of Flanders that have had the biggest impact on results and careers

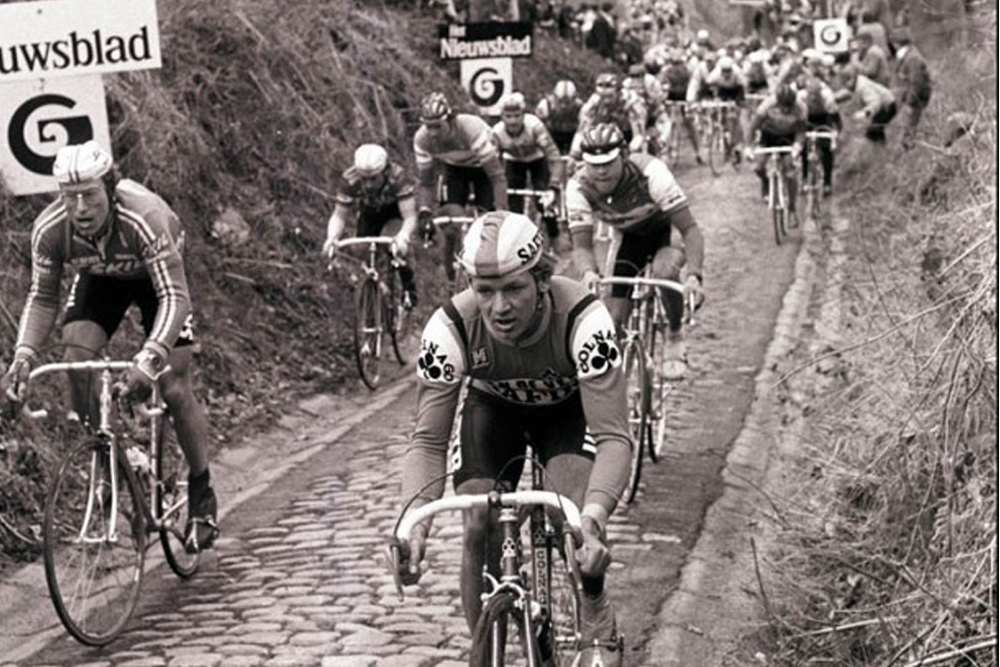

Photo: Graham Watson

The Classics are variously adored, feared and eulogised thanks to their tough sections of cobbles. These secteurs pavés can make or break the best-laid plans and set champions apart from mere riders.

Here look at the Koppenberg and run through the other defining cobbles, bergs and climbs that will likely decide the outcomes of the cobbled Classics, and in particular the Tour of Flanders.

The Koppenberg

Length: 620m, Elevation: 64m, Max gradient: 22%, Toughness: 5/5

It’s one of the toughest cobbled climbs in Flanders, a place where cobbled climbs are legion — but this one is special.

If you’re still wondering how something can be unrideable, even for professional cyclists, then you haven’t seen the Koppenberg. It rears up in front of you like a wall and the grass banks enclose you in a dank corridor as you climb. The size of the cobbles and slow speed mean that cycling up here is like sailing a dinghy into a force-10 gale.

There’s no real run-up to the Koppenberg. A 90-degree corner in Melden, the village at its foot, drops Tour of Flanders riders to a crawl. The gradient almost immediately rises out of it on cobbles. Then you hit the climb proper, and it’s brutal. It goes from 12 to 20 per cent in the first 200 metres. And there are still 400 metres to go.

In the past, the only place to ride was in the gutters, because when the Koppenberg first entered cycling its head-sized cobblestones were as rough as a mouthful of broken teeth. If the gutters were blocked riders would try the cobbles, but the camber was so great they had to be cycling gymnasts to make progress. Any kind of surface moisture caused chaos.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In its first appearance in the Tour of Flanders, in 1976, there was mayhem. The first four got up OK, then rider five spun his wheels and the rest stumbled into him.

Ten places back the great Eddy Merckx had to get off his bike and walk. Few hills have a scalp like that.

The Koppenberg played a huge part in the Tour of Flanders. Some suggested it unfairly affected the race, and that the surface was dangerous.

They were vindicated in 1987 when Jesper Skibby led the race, slipped and fell on the Koppenberg, and the car following him ran over his bike. It nearly ran over him.

Resurfaced and reintroduced

The hill was taken out of the race and spent 15 years in the wilderness until a new, €250,000 surface of Italian cobblestones was laid and the road was widened in 2001. This changed the Koppenberg but it was still a tough challenge.

Even now riding up the centre of the road requires a tip-toe application of power, plus the sixth sense of a guided missile to reach the top without stopping.

And stopping is a grim reality for many. Not only do riders depend on their own skill and power on the Koppenberg, they hope that those around them won’t run out of steam.

Slip and you are off, get baulked and you are off, stop and you are off, and the final 200 metres are a trot if one can be mustered, or a grim trudge if it can’t.

The last part of the climb eases to 13 and then to 11 per cent. Then there’s a short section of flat and a snaking descent back down to the main road.

The Koppenberg is done; 600 metres of cobbles with an average gradient of 11.6 per cent, 64 metres of height gain, and a huge place in cycling history.

Taaienberg

Length: 880m, Elevation: 57m, Max gradient: 18%, Toughness: 3/5

Tom Boonen loved the Taaienberg, and we love watching YouTube videos of Belgium’s hero putting his rivals to the sword with a blast up the right-hand gutter on this climb. These cobbles are a matter of power over technicality.

Mariaborrestraat, Steenbeekdries & Stationsberg

Length: 2,400m, Elevation: 2m, Toughness: 3/5

The undulating trio of the Mariaborrestraat, Steenbeekdries and Stationsberg show that cobbles in the Spring Classics don’t just have to be flat or uphill. Typical of the everyday cobbled roads across Flanders, they’re a ‘plug in and play’ solution for race organisers who can use one, two or all three in a race — and they are always hit at speed. In particular by the local buses.

Kemmelberg

Length: 1,400m, Elevation: 109m, Max gradient: 22%, Toughness: 4/5

Carpeted in thick-set stones laid in neat, cemented rows, the climb is the showpiece of Ghent-Wevelgem. Climbed from the south-east, it formerly included a cobbled descent down the northern face. Following a series of crashes, however, organisers decided this was a silly idea and diverted the race down a tarmac road.

Cassel

Length: 2,800m, Elevation: 53m, Max gradient: 13%, Toughness: 2/5

A number of pretty, winding cobbled ascents lead up to the town and converge on a cobbled square. Cassel is like a diet version of a cobbled climb. Just 30 minutes from Calais, it is a great place to visit any time of year except for the Monday following the Tour of Flanders when the town is full of hungover revellers.

Muur van Geraardsbergen

Length: 1,075m, Elevation: 92m, Max gradient: 20%, Toughness: 3/5

Preceding the iconic curved road up by the chapel is a kilometre slog through the town, enough to sap the zap out of most legs by the time they reach the slim brown cobbles. Like many things, the addendum up to the chapel (the ‘Kapelmuur’ to give it its proper name) is smaller in real life than it looks on TV. But it still sends shivers down your spine.

Paterberg

Length: 400m, Elevation: 48m, Max gradient: 20%, Toughness: 2/5

An exhibition in how to beautifully cobble a road, what makes the Paterberg hard is the 20 per cent gradient and a right-angled turn at the foot of the climb that kills off any momentum. Professionals will ride the final climb of the Tour of Flanders flat-out, but after 250km a small gap here can make all the difference.

Oude Kwaremont

Length: 2,200m, Elevation: 93m, Max gradient: 11%, Toughness: 4/5

A changeable, undulating climb, the crux of the Kwaremont comes near the summit when a final kick up can force a selection. Halfway up the climb is the village of Kwaremont — a small, boutique-y place with a number of resident artists and sculptors.

If you care to stop in the village square, you can even refresh yourself with a Kwaremont beer. At 6.6 per cent, it’s as strong as the climb’s gradient.

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast