Climbing The Wall: A return to America’s most feared urban ascent

Reflecting on age, memory and muscle on the climb that shaped a generation of American cyclists

The Tour. The Giro. Lance. LeMond. T-Town.

There are only a few things that most American cyclists know by just a word or two. And The Wall is perhaps the most fearsome. Probably the most feared.

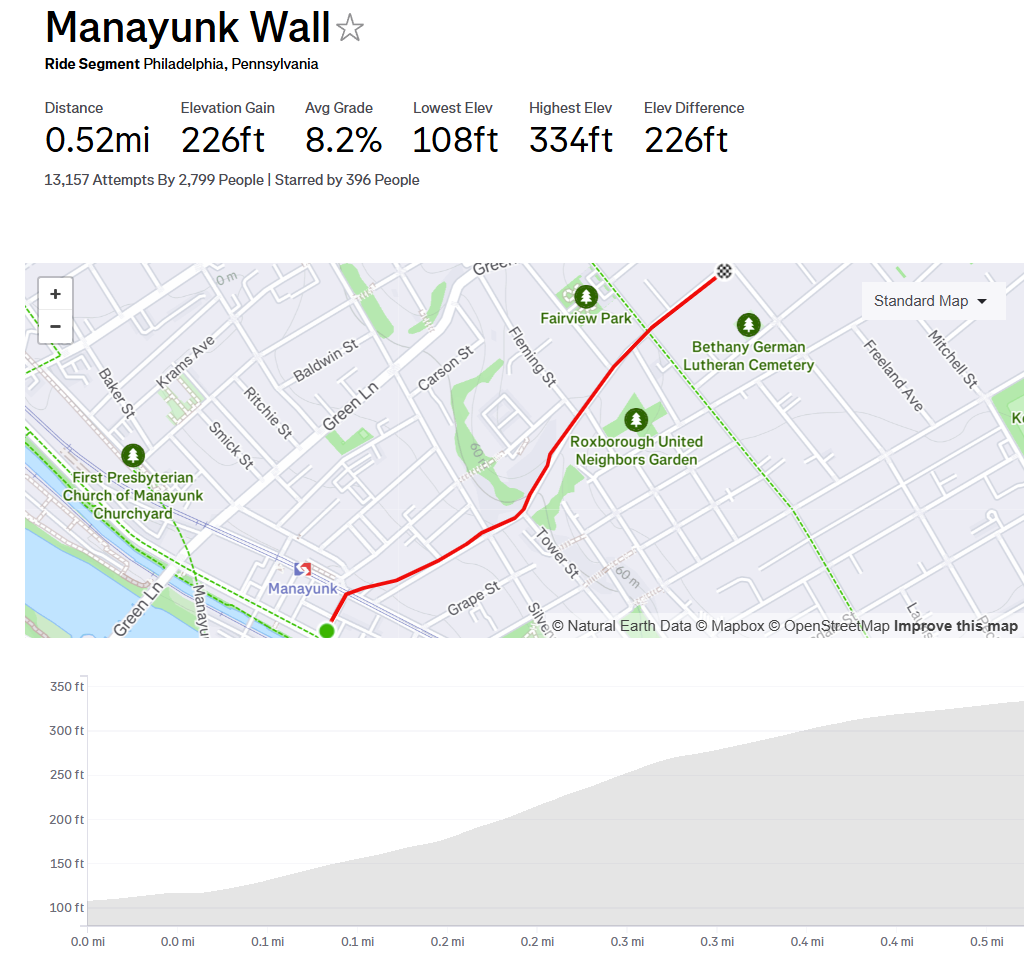

Less than a mile, averaging eight percent, with its most famous, most leg-crushing grade reaching seventeen percent, The Wall climbs up Levering Street and into Lyceum Avenue in the Philadelphia neighborhood of Manayunk.

There isn’t a granny gear easy enough, a chainring with ample teeth. No matter what size cassette you run, The Wall will grind your cadence to a slow pump and turn your legs into a fine pulp.

Philadelphia is a mostly flat city. But Manayunk is built onto a series of hills. And almost every east-west block there could be considered a wall in some way or another.

But The Wall is different. The Wall is special. The Wall is hallowed.

Maybe it’s because of that final turn beneath the elevated tracks, over the exposed cobbles that were likely laid in the era of Ben Franklin and William Penn and Alexander Hamilton. That last turn takes any momentum you were carrying in a flash, zaps all of your speed and, more importantly, all of your preconceptions. Because, no matter how many times you ride the wall, you somehow always convince yourself that this time, momentum will last a bit longer, that physics will take you just a bit further up the hill.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But science never loses. And even if That Turn didn’t exist, The Wall would still lay into you like an anchor, still suck any speed from you within an instant or two.

Maybe it’s because of the psychological element of the Levering-to-Lyceum turn, when you make that slight left

Every great climb has them. Switchbacks. When your thorax feels like a hollow cask, your legs have long become husks of themselves, and you convince yourself the climb has to end just after this next switchback, only to pedal through to turn, to look up, to see another switchback waiting for you.

The Levering-to-Lyceum turn is The Wall’s switchback. And, to put it bluntly, it’s where shit gets real. That’s where the Wall pitches up to the 17-percent grade that scars the memories of anyone who has ever ridden it. That’s where you begin to wonder if you can make it.

But most likely, The Wall is sacred cycling ground because of its feature in one of the most important and beloved American bike races ever.

Started in 1985, at the dawn of American cycling’s first Golden Age, the Philadelphia International Cycling Classic quickly became one of the most prestigious one-day races outside of Europe. In its early years, a man named O’Brien decided to set up a water sprinkler which shot a cooling shower over the street outside his house, some ways up The Wall. But then, O’Brien’s water was deemed a hazard and racers could no longer enjoy the brief respite from the stultifying heat of early summer in Philadelphia.

Over the next thirty-one years, the race became a staple of American cycling, The Wall its defining feature.

Raceday became a city-wide holiday, when the bars opened early and drunk people—whether interested in bike racing or not—lined the city streets. I’d say it was akin to marathon day in New York City but Philadelphians don’t take too kindly to comparisons to New York City. Anyway, it wasn’t quite like that because Marathon Day takes over most of the City. Whereas the Philly Classic cut through a small sliver of Philadelphia. Live anywhere else in the city and you might not know it was happening.

But there, along its course, it was electric.

Especially in Manayunk. Especially up The Wall.

Since its cancellation and removal from the UCI calendar in 2017, there have been persistent rumblings of this promoter or that financier bringing the race back to life, of restoring one of America’s greatest contributions to cycling.

Whether or not we’ll ever see a Philly Classic again remains to be seen. But The Wall, well, that’s always there for anyone with the legs and the stomach for it.

It had been almost two decades since I last rode up The Wall. It was back when I was in college, a sinewy fixed-gear obsessive, nearly fifty pounds lighter than I am today, on one of the last weeks I lived in Philadelphia. My jeans were no doubt cuffed at the ankle, my sneakers tucked tight into their pedal cages. A pack of cigarettes was likely rolled up in my sleeve so they wouldn’t be crushed in my pocket. There would be no helmet. I have no idea how fast I rode up The Wall back then, as metrics were of little interest to me. I was at the bottom and up there was the top. Riding it as fast as I could on a given day and descending without crashing were the only metrics that mattered.

But with age comes road biking and with road biking comes gears and I was thrilled at the idea of making my first go at The Wall in twenty years on a modern, carbon fiber road bike when my wife and I settled on a return to Philadelphia for an early summer vacation.

We each gave the other a few hours’ window during the week to abandon our parenting duties and go have some alone time. I’d watch both of our kids one night while my wife snuck away for some drinks with her college friends. She’d watch the kids for a few hours one morning while I went for a bike ride around my old stomping grounds.

Down John F. Kennedy Boulevard, around the Art Museum, along the verdant Kelly Drive, past Boathouse Row, out to Manayunk, up The Wall. Descend and, if there’s time, repeat.

It has to be easier, I told myself.

After all, I have gears now. After all, I don’t smoke like I did in college, back when I used to tame the wild hill regularly. After all, I’m riding and racing more than I have been since those years. After all, I live in Chapel Hill, where you’re always climbing or descending.

The day of my planned ride, of my stab at The Wall, was thwarted when I was awoken by a wall-shaking thunder and cracks of white-hot lightning outside the window of our high-rise AirBnB.

Tomorrow.

The following morning was hot and humid, as it always seems to be in a Philadelphia June and my mind immediately raced back to all of those bike races I watched in college, as the pros zoomed by in a flash of Lycra. Those mornings were always gross, just as this, and I thought of those pros and how that affected their performance and I thought of O’Brien’s house, near the top of The Wall and how he used to hose the racers down. I never saw O’Brien’s house but I knew of the legend. And in the heat, I remembered my denim and my t-shirts and the smokes and all the summers I spent in this swampy city without air conditioning.

And I thought of how much youth can overcome.

In my case, cigarettes, gears, jeans, heat, and dehydration. I spent most of my time drinking, partying as college kids do, and still managed to ride my bike a lot. How much, I’ll never know. Metrics didn’t matter back then.

None of that mattered when I was twenty-one or twenty-two years old.

Now, donned in high tech cycling gear, in aerodynamic, sweat-wicking kit; with one bottle of plain water and one of electrolyte-enhanced sports drink to keep my muscles and my organs hydrated; with twenty-one gears and a stiff, lightweight carbon fiber bike; with my tiny, handlebar-mounted computer that tells me exactly how many watts I’m creating, exactly how many times my heart is beating each minute, and exactly the grade I’m climbing up, I had every advantage over the young man I was.

Climbing The Wall should be a breeze. Well, as much of a breeze as climbing a seventeen-percent grade could possibly be. Of course, the only advantage the young man of back then had over the grown man of now were those fifty extra pounds that didn’t exist. That and the bliss of ignorance, of not knowing what seventeen-percent grade even meant.

I pedaled up Main Street, the Schuylkill River to my left and the rising hill of Manayunk to my right. I found Levering Street and took a few final deep breaths before hitting the quick right-left, under the El train and over the ancient cobbles, before the climb started.

And, just as it did then, The Wall stood before me, just as magnificent and terrifying as it always was and always will be. And, just as it did then, my brain had to remind my legs that they could do this, that they’ve done this a hundred times before. And, just as it did then, my bike slowly began to make its way up The Wall.

As I bolted into The Wall’s lower slopes, I reminded myself of an adage I often tell new riders: “Listen to your legs, not your eyes.”

Your eyes will deceive you, make you shift too soon. Your legs never lie. And so, I fought every instinct to shift into an easier gear with each passing pedal stroke. Soon, however, I had to start shifting. It was unavoidable. And as soon as I did, I stood on my pedals, using every ounce of my 255 pounds to force more power into my pedals. I reminded myself that there was still so much more to climb, of the inefficiency of climbing out of the saddle, sat back down, and found a nice rhythm well in excess of 90 rpm.

Soon, however, I came to the dreaded stretch of 17-percent pitch and those 90 became 80. Then 70. Then 65. And I only had one gear left on my cassette. It’s a gear I try to never, ever use. It’s one I call “The Mental Gear,” because, knowing I still have a gear should I need it works wonders on my mental state in the throes of a climb.

It’s when you run out of gears that you’re totally screwed.

I strained my neck upward in hopes of seeing the green sign “Fleming Street,” where The Wall begins to level out toward its finish. I counted my strokes. I refused to shift into that final gear. I imagined a rainbow of water arching over the street from O’Brien’s house.

Eventually, I rolled over the top. My head slumped down as I fought to keep my elbows bent. I realized it had been nearly twenty years since the last time I soft pedaled across Manayunk Avenue, The Wall in my rearview.

Was I faster? Who knows? A broke young college kid, I could barely afford new tires let alone a bike computer. Anyway, back then, making it to the top was the only metric that mattered.

According to Strava, 2,799 bike riders have climbed The Wall. We all know that the actual number dwarfs that. But for the purposes of this essay, let’s stick with that very easily definable number.

On June 5, 2016, in the final iteration of the Philadelphia International Cycling Classic, an Italian racer named Marco Canola, then riding for United Healthcare Pro Cycling Team, climbed The Wall in 1:56, still the segment’s KOM. Barely a year earlier, he won a stage at the Giro d’Italia.

That same afternoon, another Italian finished the segment in 2:19, which, to this date, remains the QOM. Since then, Elisa Longo Borghini has won Paris-Roubaix, the Tour of Flanders, the Giro d’Italia, Strade Bianche, and the Women’s Tour, amongst countless other races. She spent the last decade racing herself into the pantheon of history’s greatest bike racers.

It took me a bit longer on that hot, swampy, early June morning, even with all of my gears, my lycra, my electrolytes and the fact that I hadn’t had a cigarette in years.

From Main to Cresson Street, up Levering to Lyceum, past Dexter Street, past O’Brien’s, past Manayunk Avenue, and finally up to the intersection at Pechin Street took me 4:15, more than double Canola’s time. As of this writing, that 4:15 makes me the 1,725th fastest ever to climb The Wall. Or, at least the 1,725th fastest to log the climb on Strava.

Of course, I’m a big guy and so I usually toggle my Strava climbs to see how I stack up against other big guys. No sense in racing someone who weighs a hundred pounds less than me up a mountain. And so, it’s a bit more impressive if you toggle to the Clydesdale class. There, in the 250lbs+ category, my 4:15 is good for fourteenth fastest.

These are not numbers that I care much about. After all, I’m a recreationalist in my forties, twice the size of most elite climbers. Still, it’s fun to see where I stand, to imagine myself in a race against those other 2,798 riders, trudging from bottom to top. To finish somewhere in between.

But maybe I was on to something twenty-plus years ago. Not with the jeans, of course, and definitely not with the smokes. But maybe there was something to simplifying the metrics.

The bottom is where you start. The top is where you finish. The middle is where you suffer. That’s it. That’s all there is to it. After all, when a place such as The Wall has reached legendary status, isn’t the simple act of riding it enough?

Michael Venutolo-Mantovani is a writer and musician who has been riding and racing bikes in one form or another for nearly forty years. He's an avid road and track cyclist, a reluctant gravel rider, and a rather terrible mountain biker. At the urging of his six-year-old son, he's recently returned to BMX racing for the first time in thirty-one years. His favorite ride on Earth is the Col de la Forclaz, high above France's Lake Annecy. He has contributed to the New York Times, GQ, National Geographic, Wired, and Condé Nast Traveler. Though he's recently fallen madly in love with London, Michael lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA with his wife and their children.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.