Mandy Jones: An accidental champion

Thirty years have passed since Mandy Bishop won the World Championship road race at Goodwood, but the significance of that victory and her career should not be forgotten. In the 1980s, Bishop was British cycling's tenacious world-beater, paving the way for the sport's modern stars without the cosseted backing that many enjoy nowadays.

On the dole and often taken to races by her parents, Bishop started racing in men's shorts on an oversize frame. An overriding passion for the sport permeated her pedalling: she was happy doing long-distance touring round the Dales or racing the women's Tour de France. Precocious talent and a fierce competitive nature helped her to the top, but it came with mental fragility and ruinous injuries. This is Mandy Bishop's story in her own words.

"I was wearing my GB tracksuit and I had to ride round the Goodwood circuit to get back to the hotel. I kept stopping and waiting for the men's race to come past and then I'd cycle the next bit. Then I got to a policeman who stopped me and said ‘you can't ride down here'.

"All the crowd on the roadside were shouting at him ‘don't you know who she is? You've got to let her through, she's just won the World Championships!'"

Parental guidance

"I'm competitive when I get on the bike, but I'm not a driven person. My dad was the one who made me love cycling. He used to take me to all the races and was always dead encouraging: some parents get annoyed and shout if their kids do badly, he was never like that.

"When I was nine or 10 he joined West Pennine Cycling Club in Rochdale and the whole family started going out on club runs and youth hostel weekends.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"Once I got going, I did a couple of 10s as a teenager and got fitter. But I didn't really ever train. We did summer holidays touring and cycle camping in the Lake District and cycle camping for two. It was a very traditional club upbringing. It wasn't till I was 16 [in 1978] that I started road racing, training and getting better.

"I started on a Sturmey-Archer three-speed bike my dad built for me and rode fixed wheel until I was 16. Then a friend sold my dad a Woodrup, fully equipped with a Campagnolo groupset. It was a bit big for me - a 21.5in frame, and I ride 19 and a quarter now. Dad probably thought I'd grow into it.

"Then my ex-boyfriend [Wightmann rider] Ian Greenhalgh started coaching me and I went out training with him and [team-mate] Jack Kershaw. They didn't make any concessions to my ability level.

"I was used to the distance because of club runs but when I was training with Ian, he never let up. I could never beat him on a climb, he always pushed me to the limit all the time. Occasionally I cracked. I remember standing at the side of the road, breathless and crying my eyes out, it was like having a panic attack.

"But it was all I wanted to do because I was very competitive. I suppose it made a massive difference. When I raced abroad, I could compete on the level of the European riders, who did different training and had a lot more races. Here in the UK, I'd ride time trials and the track - you rode every discipline because there weren't many events.

"I really liked time trialling because no one could sit on me - it was difficult for me to get away in a road race sometimes - and I could just concentrate on riding as fast as I could. Once I started winning events, I quite enjoyed seeing how far up I could finish in an open event, I think sixth was my best.

"I raced against Beryl Burton [Bishop was the first to beat her in 20 years of RTTC competition in 1982] and we spoke a couple of times. She was very nice but I think I probably felt overawed, I wouldn't have known what to say to her at that age.

"Some men were very supportive and thought it was wonderful. But others didn't like it and could be patronising. I remember when after riding a ‘10' on the Chester Road, everyone was crowded round the results board. I'm stood in front of two guys, let's call them George and Eric. George says ‘why didn't you race today?' Eric replies ‘what, and get beaten by a bloody woman?' That kind of attitude: he didn't want to race because he might get beaten by me to the point it would ruin his day!"

Getting results

"I didn't understand the natural ability I had till I started winning things. But it takes time for that to come, I certainly wasn't naturally confident as a teenager. I got a completely unexpected bronze at 18 in Sallanches [in 1980], it was my first year racing abroad and it was on that over-geared Woodrup.

"I was sponsored, shall we say - I was on the dole. My parents were happy to take me to races and I'd give them petrol money, as I couldn't drive till I was 28. It was a choice of either training full-time with the aim of winning the Goodwood World Championships - which was always the aim - or get a job and do it part-time, like everybody else seemed to.

"There was no major support, bits of grant money from Sports Council and local authorities and that. Racing abroad with GB, we kept the skinsuit, but the rest you had to give back. The shorts and jersey we raced in were men's most of the time. It was nothing like it is now, British Cycling just didn't have the money.

Worlds winner

"I wasn't nervous before the World Championship race in Goodwood in 1982 because I'd messed up the world individual pursuit a week before. The reason was because I was knackered: I had trained behind the motorbike for speed work until three days before the finals.

I said at the time that I'd quit international racing, I was extremely fed up. That result almost took the pressure off because I thought ‘I've blown it'. I had a week before the road race and was very relaxed about it, which was unusual for me. Of course, when it came round, I'd had a week's tapering and I was flying.

"We only rode the course the day before: we were up north, Goodwood was right down by the south coast. The distance was 40 miles, they put it up soon after.

"The GB team was me, Margaret and Catherine Swinnerton, Julie Earnshaw and Pauline Strong. We were individuals who mostly rode against each and got together to ride as a team for international events. The idea was you rode as a team, but it didn't flow the way that it does nowadays: by the time we did the first circuit, the field was split to smithereens, I think it split up every time on the climb. So really, I was on my own.

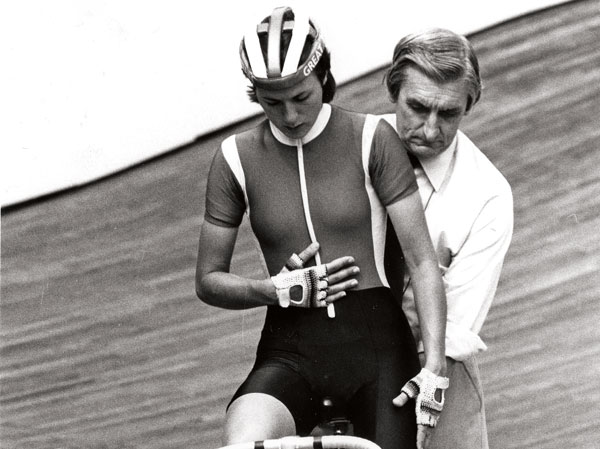

"Team manager Jim [Hendry] told us to try to get on the front line as host nation. He was holding me up on the start line and I missed my pedal but that was the only problem I had.

"From the word go, the race split up. With a lap and a bit to go, the Italian Maria Canins, Gerda Sierens from Belgium and Sandra Schumacher, the Frenchwoman, escaped. I'd just been caught and had to make a big effort to get on the back. The four of us then got away.

"Over the top of the Goodwood circuit climbs, goes into a long, flattish road before turning into a descent. It was as it turned the last time that I got away - downhill. Which I thought was really odd.

"It wasn't a particularly hard attack either, I went round the corner first, really got going, looked around, saw the gap and put my head down and went for it. That was it, I never saw them again. My ability was climbing, but on that occasion, my time trialling really helped.

"I rode a very positive race. When everything comes together like it did that day, you don't think about it: you're in the zone, making the moves. That's what you train for. Even when I watch the race now, it's like watching somebody else. I think ‘ooh, she did quite well'.

"The crowd on the climb was unbelievable, I remember it to this day. You're never in pain when you win - whether it's a fish and chipper, Nationals or Worlds.

"I realised straight away what I'd done. My parents and Ian were there; there wasn't a dry eye in the house. I didn't even get to have a shower till about three hours later. They whisk you off to do interviews and things, then I had to ride back to the hotel - and that's when I bumped into that policeman.

Fast fame

"Winning the road race at Goodwood was like a mantra. I should have made it more phased rather than one big three-year goal. That's why I switched off and found it difficult. We never discussed ‘what happens if you win?'

"It was a whole new experience, newspapers came round for interviews and photo shoots, I did A Question of Sport, dinners, odd bits - not as in demand as cyclists nowadays. The immediate aftermath was going from the front page of the local Rochdale newspaper to the nationals.

"What suffered was my bike riding.

Ian pushed me very hard and it got to the point where I had no motivation, I was sick to the back teeth of training. I felt like I had no life outside of cycling - a bit like the situation Victoria [Pendleton] describes in her book.

"When I won the rainbow jersey, it was almost like a cut-off point - I thought ‘I've done my job'. But of course you can't just stop as reigning champion. In 1983, I didn't do myself justice [Bishop was fourth in the World Championship road race and National 10 and 25-mile champion]. I took the following year off and recovered a bit.

"But I developed a calf injury in the winter of 1983 which went undiagnosed. It used to seize up during racing, I had to pull out of the women's Tour de France with it when fifth overall. After I'd won the 10 and 25-mile national time trial in 1985, I couldn't walk afterwards, I was riding through the pain.

Two quacks said to me: "There can't possibly be anything wrong with that leg because you wouldn't be winning National Championships in this much pain". So I started to doubt myself and wonder if there was anything really wrong with me.

"I had my son Sam in 1986 and the calf was operated on. I came back in the early Nineties and that's really when I got support and scans because I was on the Olympic squad. It got to the point, I didn't have time to get fit for the [1992] Olympics, and I didn't want to go to ride around if I wasn't 100 per cent fit, unless I had a chance of winning.

"I was really fed up for a number of months after that. I was forced to quit, the decision was taken out of my hands. Later, I got into fell running and mountain marathons with my husband Nigel [Bishop, ex-Milk Race leader and GB rider]; if anything, because we needed something to do. I do a lot of running up and down the stairs at work [Bishop runs Surosa Cycles in Oldham] and I only ride the bike at weekends.

"My rainbow jersey is up in the shop, but a comeback isn't on the cards. I have thought about it over the last few years but when you've ridden at the level I have, I couldn't race for racing's sake. I would want to win.

"It has all changed now and I think it's absolutely fantastic what's happened, the fact they've got coaches, masseurs, psychologists. Because it's tough to do it like we did. I don't have any regrets, there's no point. I know those who've stopped and never touched the bike again With me, it was never just for the competition: that was an added bonus to riding my bike."

Jumping the generation gap

Having experienced being ill-prepared for success as a 20 year old, Bishop has advice for the likes of junior world champions Lucy Garner and Elinor Barker. "They have the support crew around them I didn't have. I had parents and things, but they didn't understand, nobody understood what the aftermath of winning a World Championships was going to be like.

"It's good to get advice from people close to you. The other thing is, don't feel obliged to do things - I felt obliged to go to lots of dinners, and it didn't do me any good. I know people want to see you but you've got to keep up your training."

Bishop feels the difference between her generation and the contemporary crop comes down to availability of racing and free time. "The quality of riders was no different but we didn't race as much, as far or train as hard. We couldn't: most of the other girls were still working.

"In the middle of the year, there were no international events to go to till you went to the Worlds. That's where you'd find the gap widened most between home and international riders, it was the way it was set up. Nowadays there are more women just riding bikes, which is a wonderful thing to see."

Tech has moved on apace too; Bishop got a buzz from riding special silk tubs for National Championships and using tri-bars, which hit the time trialling scene in the late Eighties.

BISHOP on...

Reuniting the old gang

"We had a bit of a reunion at Maria Blower's house in Surrey for the Olympic road race last summer. It was me and Nigel, Julie Earnshaw, Lisa Brambani, Allan Gornall, Chris Walker, Brenda Tate, Colin Sturgess - he got the treehouse, the best room, while we were camping - and a few others. I hadn't seen some of them for 20 years. We had a party, watched the race on the telly and ran down the drive to watch it pass."

Jeannie Longo

"She wasn't a nice person, she would happily thump people if they got in her way. We rode this mini stage race round France and Brenda Tate, our sprinter, won a stage after sitting on the back. On the podium, Longo started having a go at her. We thought that was hilarious: that's how you win races if you're a sprinter."

This article was first published in the February 14 issue of Cycling Weekly. You can also read our magazines on Zinio, download from the Apple store and also through Kindle Fire.

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.