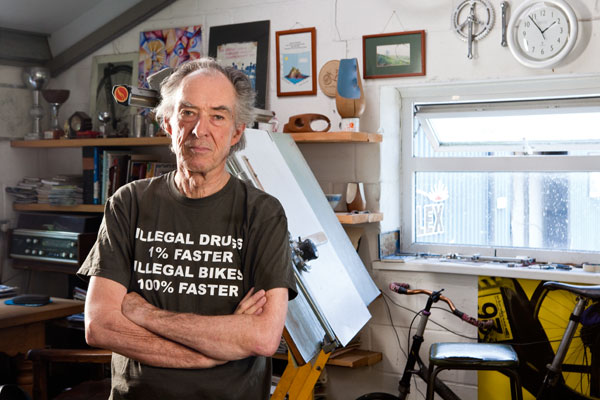

Mike Burrows: cycling innovator

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cycling is being let down by modern bikes which aren't modern enough. This is the radical verdict of Mike Burrows, the man behind Chris Boardman's 1992 gold-medal-winning Lotus pursuit bike and the world's first compact road frame, the Giant TCR.

And he lays the blame squarely at the feet of the UCI."It's very frustrating," Burrows tells CW. "The UCI won't let manufacturers make the bikes better, so they have to make them different for commercial reasons.

They tend to alternate, getting worse for a couple of seasons, then better for a couple of seasons. "Manufacturers are making funny-shaped tubes because they have to. Round is the shape for a down tube. Aerodynamics for a time trial bike and a bit of ovality makes sense, but square and triangle? It's a load of nonsense, but that's marketing.

It's terribly sad because all these bikes could be so much better if the UCI allowed them to be, but with the minimum weight and various design restrictions that are imposed, it's ridiculous."

Exotic machine

"I don't think the UCI even understands what it should be doing. They should be encouraging cycling generally - racing can look after itself. It's cycling in the greater world that we want to have a more positive image, and you get that from the bicycle being seen to be exotic."

After designing the Lotus - which the UCI eventually outlawed - and seven years at Giant, Burrows, now 70, is officially semi-retired, although still busy working on his 8-Freight utility bikes, various other projects and enjoying life racing his Ratracer recumbents with the British Human Power Club.

"Unlike Graeme Obree, who used to get a bit stressed out, I've just gone away into the world of laid-back cycles, which is really nice," Burrows says. "As well as going fast, they're also comfortable. But they don't get much coverage in the cycling media, and a lot of people just don't know they're out there."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Asked what excites him these days, the answer is typical Burrows: "The new bike I'm building! There's nothing much else. The problem seems to me that the bike industry got into carbon without fully understanding it. Carbon is wonderful stuff, it has more potential than anything else on the planet, but so many companies don't know how to use it.

"For example, some firms are cooking the bottom bracket shells in when they cure the frame, but aluminium expands and carbon fibre contracts when it gets hot. So when it cools down the bottom bracket shell flops out.

"I think part of the problem is that the cycle industry doesn't always attract the highest achievers. The bike industry is spread so thin that there's not that much money to be had, or areas to spread into.

"The boss of Giant UK for a while, Ian Taylor, was an Olympic hockey gold medallist. He made Giant the top brand in the UK for mountain bikes. But when he'd done that there was nowhere for him to go. He'd achieved all he could achieve, so he left the bike trade. That means the people involved aren't always as knowledgeable as they could be, so when the UCI bans things, these people just go with it."

There are some exceptions though - notably his old Lotus pilot. "Boardman bikes are brilliant. Chris doesn't know everything about bikes technically, but he is a great manager - he should be running British Cycling. But his bikes are brilliant: coordinated colour schemes, nice subtle graphics, good value for money.

"And there's the Gocycle [high-quality, lightweight electric bike]. Its designer, Richard Thorpe, has been inspired by a few of my ideas and they've made a nice little bike."

Missed opportunity

It's at the very top end of the sport where the biggest advances could be made, according to Burrows. While people in cycling are always keen to highlight athletic progress, from an engineering perspective it's where the biggest developments could be happening.

"No one at British Cycling has spoken to me ever since I got into trouble with the Lotus," Burrows says. "These days they don't want people to talk about the bikes; they only want people to talk about the athletes, which is stupid. It's getting people on bicycles that matters, and the trickle-down effect.

"When the UCI was trying to ban Giant TCR frames, the only company that would stand with Giant was Cinelli. They'd had the Spinaci bar extensions banned.

Antonio Colombo [Cinelli president] was telling me what amazed him wasn't that people stopped buying Spinacis, but the old boys riding along the Côte d'Azur took them off their bikes. Not because they didn't like them, but because their heroes weren't using them any more.

"That's how influential the Tour de France is. And if people's heroes ride more modern, more progressive bicycles, then that will reach everybody, and we might have more people riding bicycles.

"Could you imagine what it would be like if the Tour prologue allowed the boys to go round just inches off the ground on my racing recumbents with part fairings on them? It would be superb. People would be saying: ‘That's cycling? Bloody hell, it wasn't like that when I was a boy!'"

What not to design

"The down tube takes two-thirds of the load on a normal diamond-frame bike so that tube has to be round. No ifs, no buts. Unless it is a time trial bike and there is some aerodynamic consideration in which case you ovalise it slightly, and fastback it slightly and Kamm-tail it - that will give you the best airflow combined with stiffness. Anything else is nonsense," Burrows says.

"The BB30 idea makes a lot of sense - in fact I tried to introduce a bigger bottom bracket shell but I was ahead of my time. It's very difficult to make a bicycle if the bottom bracket shell is smaller than the down tube. It's much better that the BB shell is bigger than the tubes, like it used to be when we used 531.

"Where manufacturers press BB30 bearings into a carbon-fibre housing is not good. Carbon is very strong but carbon composite relies on the resin bonding it together. So if it moves, and wears a bit, and moves and wears a bit again, it's finished. And you've wrecked a £3,000 bike."

20 years on

It is 20 years since Chris Boardman and Graeme Obree both broke the Hour record, and Mike Burrows was involved in each riders' bike choices. Check here for more

This article was first published in the July 25 issue of Cycling Weekly. Read Cycling Weekly magazine on the day of release where ever you are in the world International digital edition, UK digital edition. And if you like us, rate us!