Giro d'Italia 2017's toughest climbs: one down, five to go

With the Giro d'Italia well underway, here's a guide to the major climbs that will shape the race

Mount Etna.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Giro d'Italia wouldn't be the Giro d'Italia without serving up a selection of testing climbing challenges over its three-week course. And the 100th edition of the race includes some of the race's – and Italy's – most famous and daunting mountain challenges.

Here, we pick out six of the climbs in order of their appearance that should provide plenty of action as the opening Grand Tour of the 2017 season unfurls.

>>> Giro d'Italia 2017: Latest news and race info

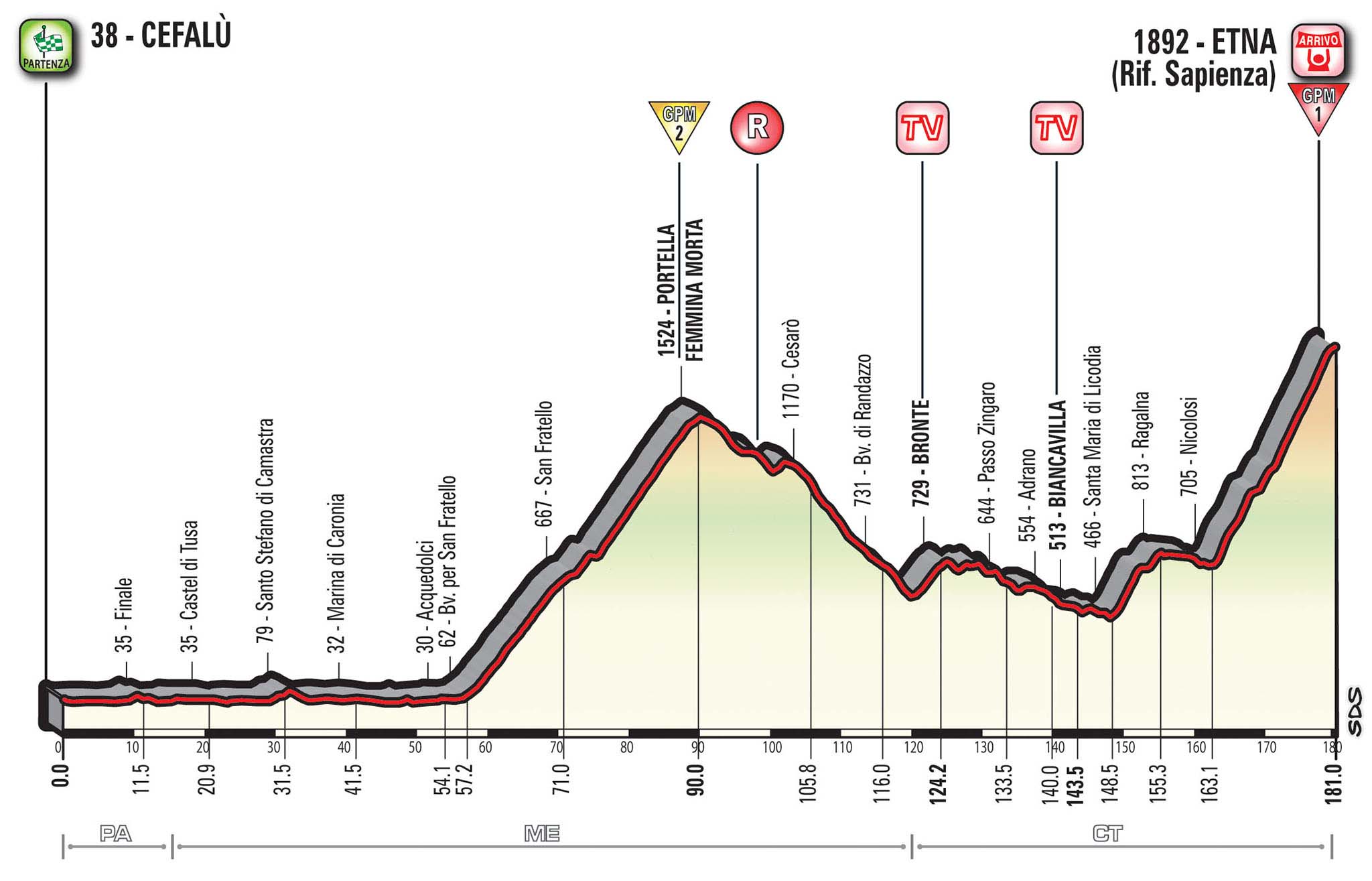

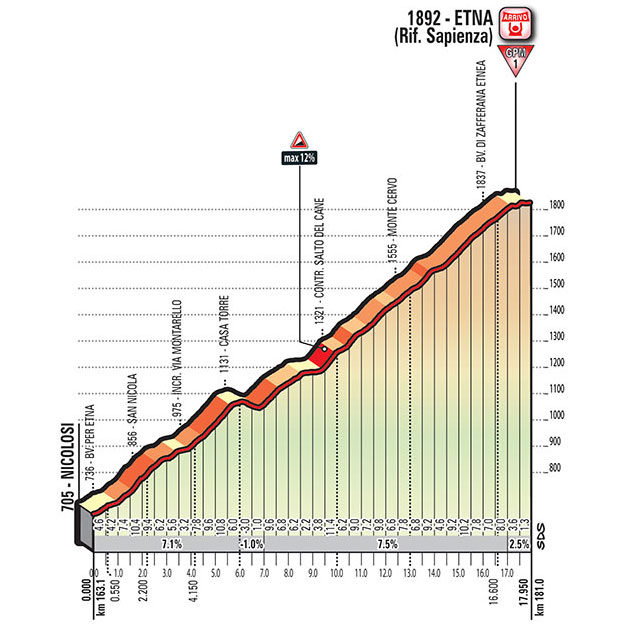

Mount Etna - already complete

Stage four, Tuesday May 9 - race report here

Category: 1

Length: 18km

Average gradient: 6 per cent

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Maximum gradient: 12 per cent

Maximum elevation: 1,892 metres

You may recall that a BBC film crew were caught in an eruption on Mount Etna in March this year, when they were pelted with hot ash and boiling rocks. That's the same climb that featured in the first mainland stage of the 2017 Giro, creating a thrilling final test for the peloton at the end of stage four.

The climb did indeed prove pivotal. At 18km it was the final test for Jan Polanc, who slipped away with a break group of four in the opening kilometers of the race and was the only one to hold his lead until the finish line.

The climbs still to come

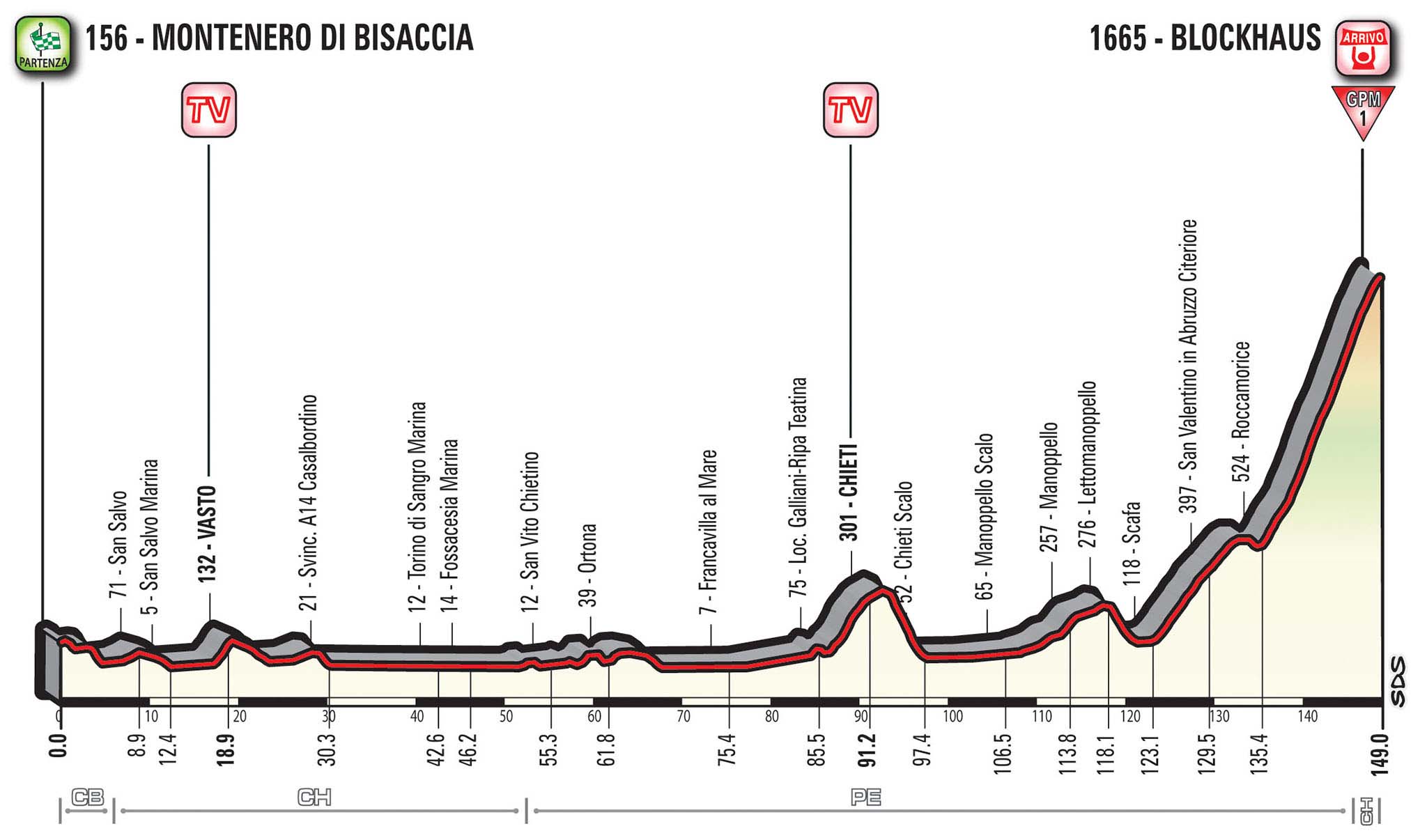

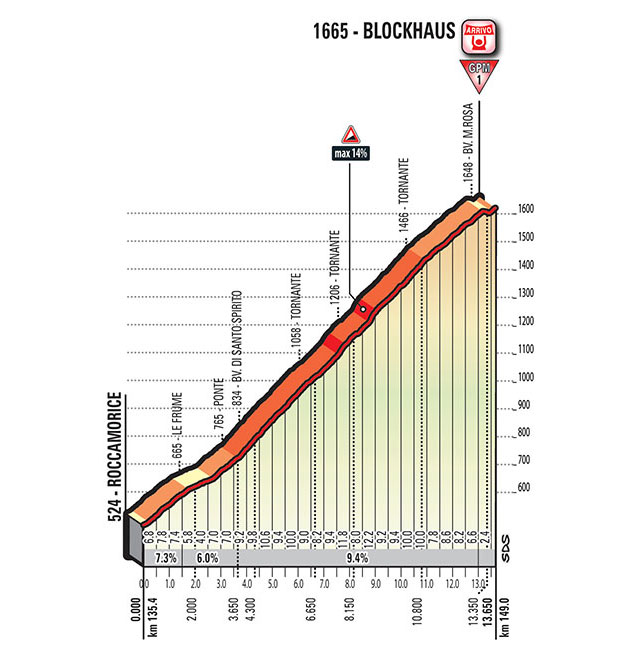

Blockhaus

Stage nine, Sunday May 14

Category: 1

Length: 13.6km

Average gradient: 8.6 per cent

Maximum gradient: 14 per cent

Maximum elevation: 1,648 metres

Although there are a collection of unclassified climbs prior to the arrival of the stage nine's final ascent of Blockhaus, there will be little to prepare the riders for this stern test – possibly the hardest climb of the entire race. The narrow road twists through the wooded landscape on a relentlessly steep incline, reaching 14 per cent in places but more importantly averaging nearly nine per cent.

>>> Giro d'Italia 2017 route: Stage by stage

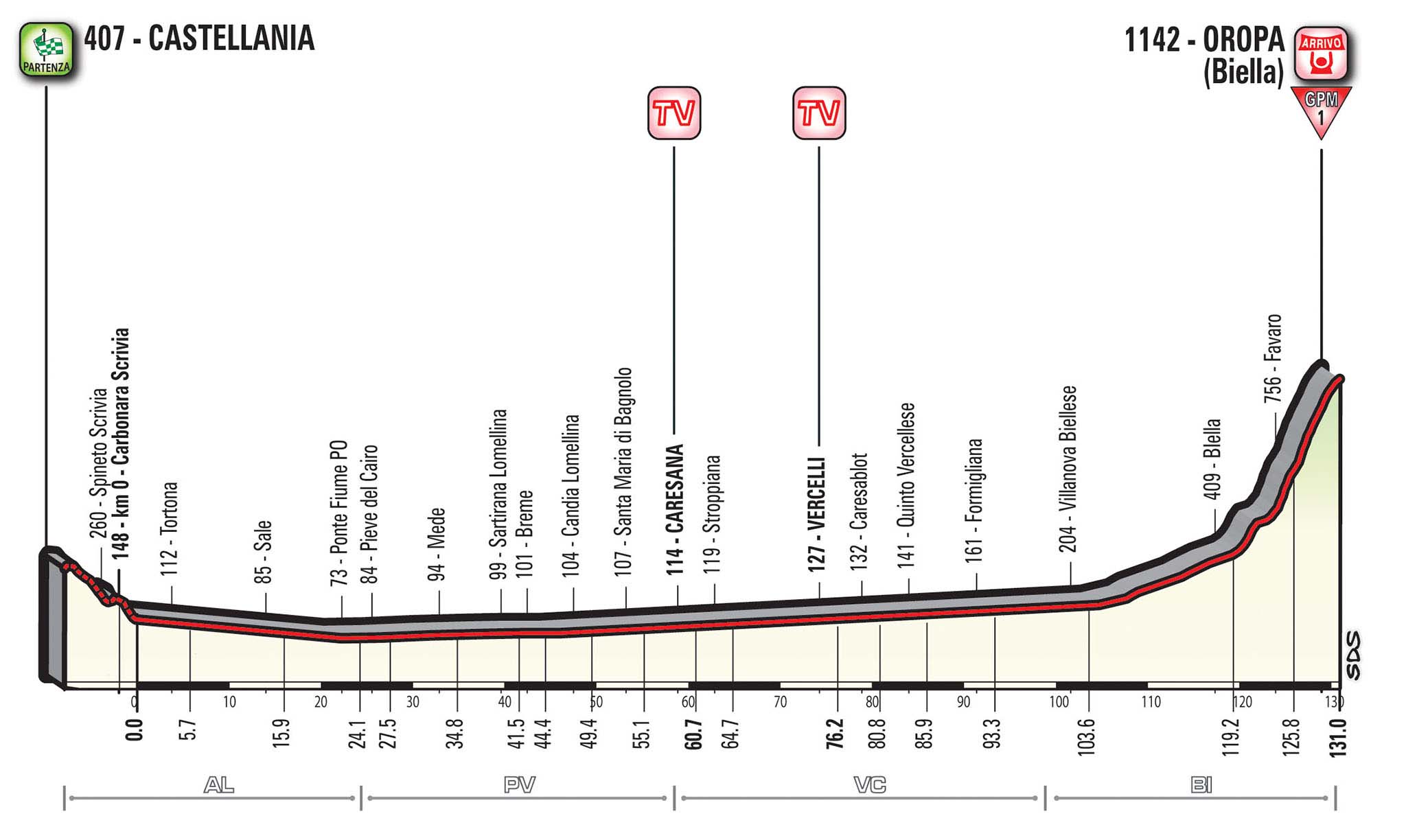

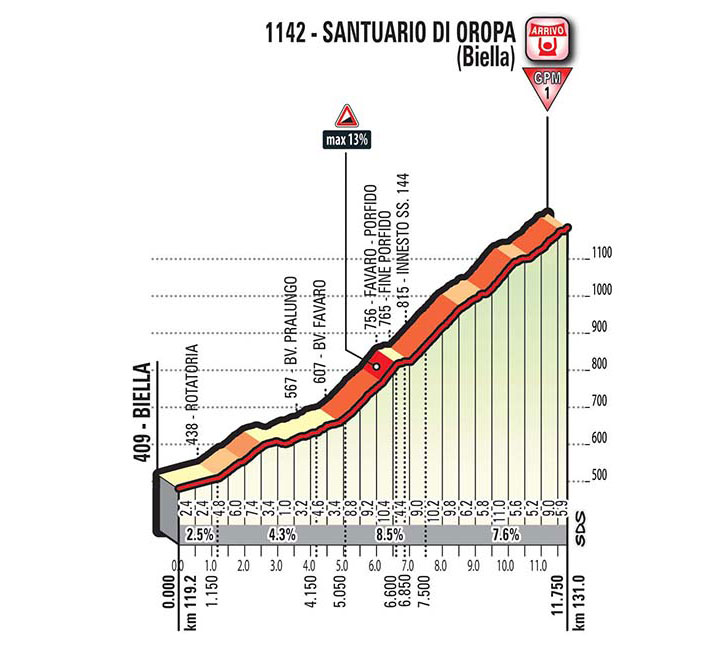

Oropa

Stage 14, Saturday May 20

Category: 1

Length: 11.75km

Average gradient: 6.2 per cent

Maximum gradient: 13 per cent

Maximum elevation: 1,142 metres

The stage profile looks more like something you'd find in a skate park that in a Grand Tour – albeit on a much, much larger scale. A descent from the start and a relatively flat day has 'escape group' written all over it. Equally, the final ascent to Oropa has 'escape group caught' written all over it.

The climb's fluctuating gradient will do little to aid riders in finding a rhythm on the tricky climb, and will therefore favour those who have a more explosive nature (Nairo Quintana) than those who grind it out (Tom Dumoulin).

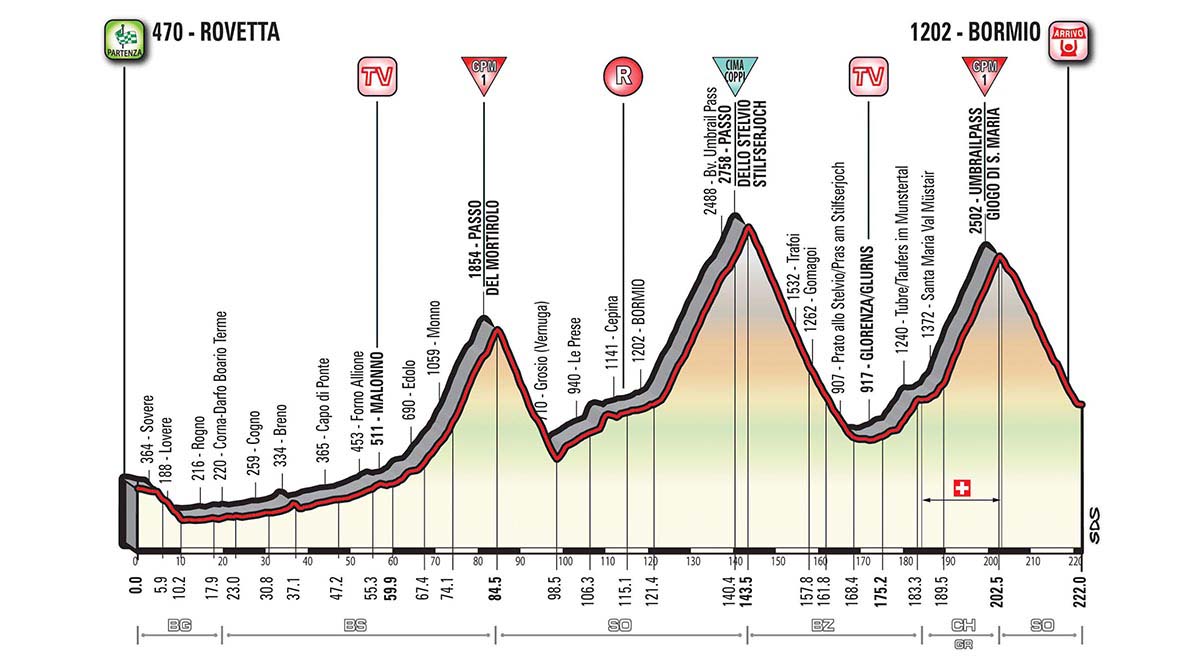

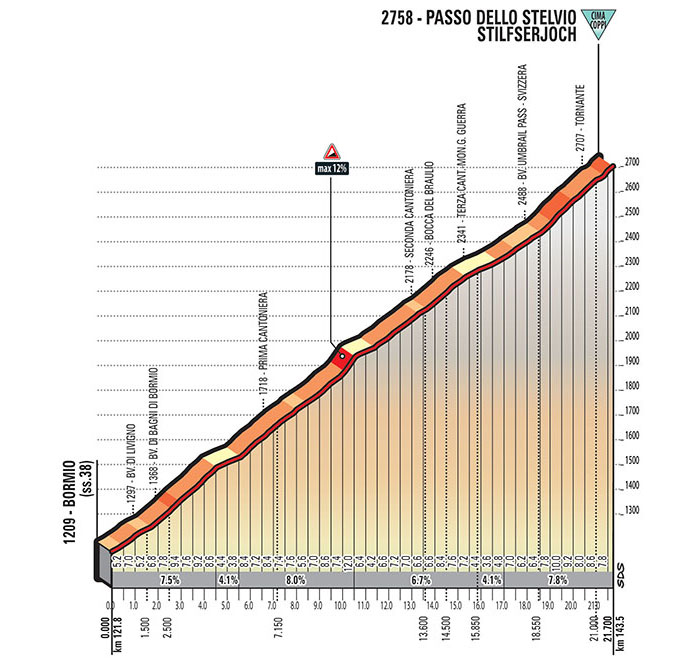

Stelvio

Stage 16, Tuesday May 23

Category: Cima Coppi (highest point in race)

Length: 21.7km

Average gradient: 7.1 per cent

Maximum gradient: 12 per cent

Maximum elevation: 2,758 metres

Riders tackling the mighty Stelvio not only feel as though they are climbing into the sky, but must also feel as though they are winding the clock back to winter. Accumulations of snow at the roadsides and cuttingly cold winds are a general feature on the pass, even in mid-May.

Even without the weather factored in, the 21.7km ascent reaching an elevation of 2,758 metres above sea level will have the riders gasping, particularly as they will have already crested the Passo del Mortirolo – recently announced as a climb in honour of the late Michele Scarponi – and the following Umbrail Pass.

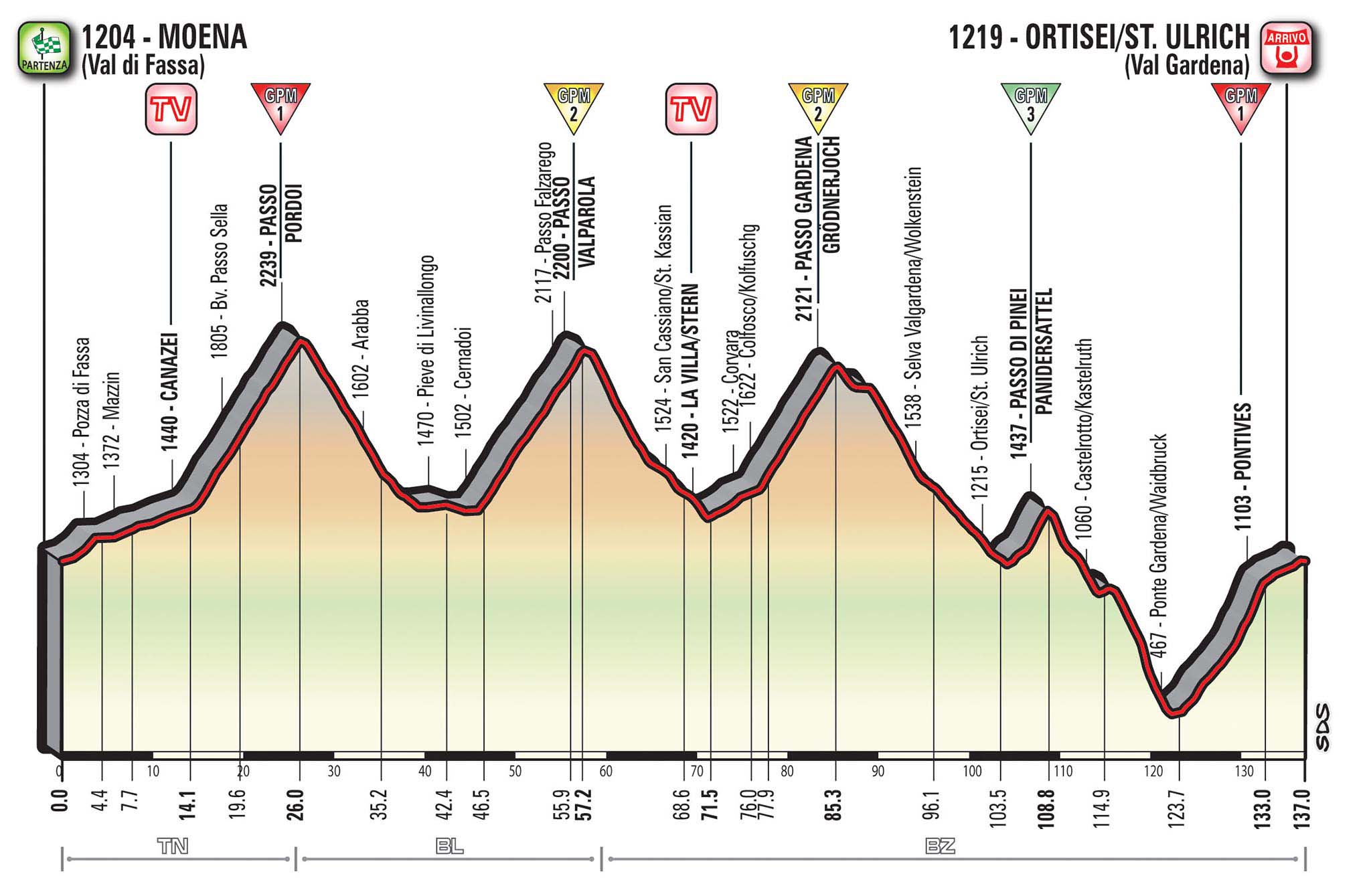

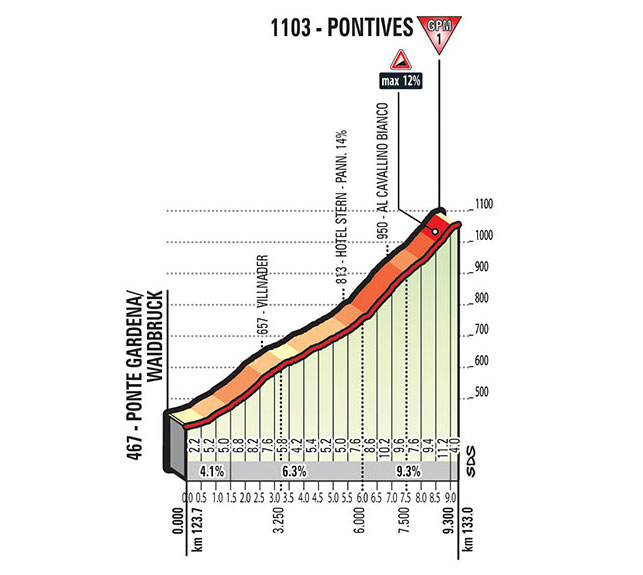

Pontives

Stage 18, Thursday May 25

Category: 1

Length: 9.3km

Average gradient: 6.3 per cent

Maximum gradient: 12 per cent

Maximum elevation: 1,103 metres

It's hard to pick out which of the stage 18's mountains are the toughest. The stage is billed as the 'queen' climbing stage of the 100th edition, and features five categorised climbs in a relentless sawtooth profile across the Dolomites: Passo Pordoi (Cat 1), Passo Valparola (Cat 2), Passo Gardena (Cat 2), Passo Pinei (Cat 3) and Pontives (Cat 1).

The final classified ascent of Pontives is sited four kilometres from the finish line, and will therefore be decisive in the day's war of attrition. Worst of all for tired legs will be the sting in the climb's tail, a short section of 12 per cent gradient before the climb's peak and then a descent across cobbles to the finish.

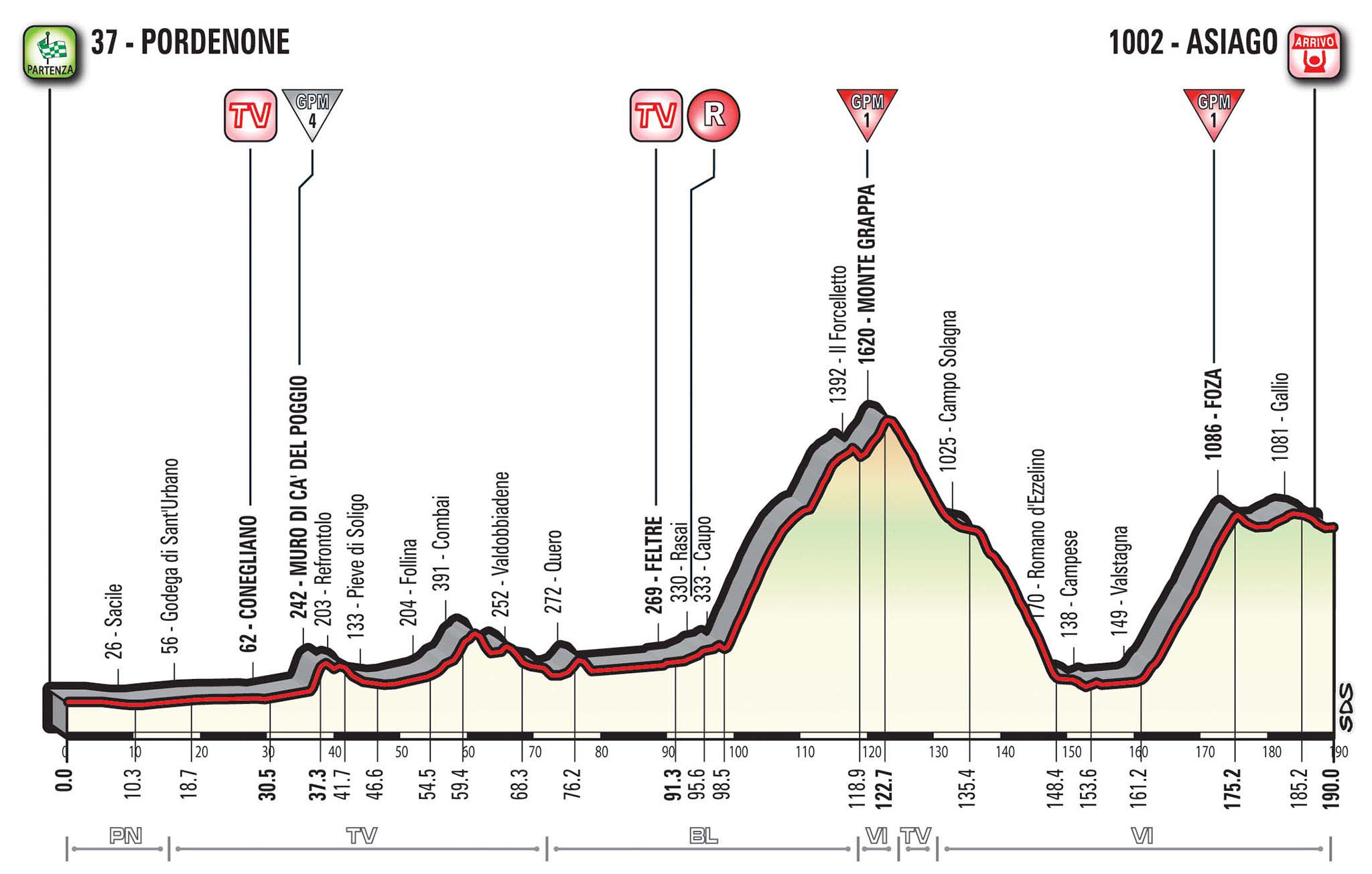

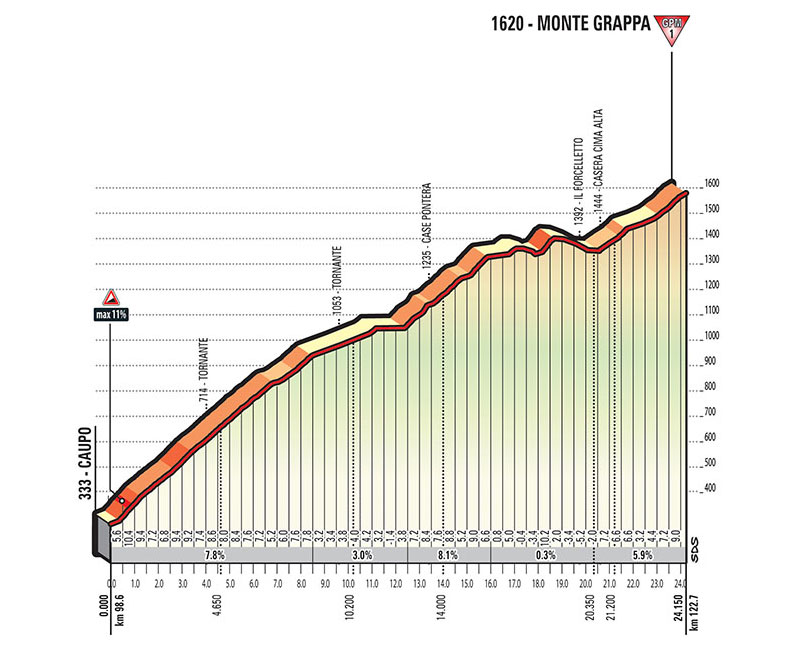

Monte Grappa

Stage 20, Saturday May 27

Category: 1

Length: 24.15km

Average gradient: 5.4 per cent

Maximum gradient: 11 per cent

Maximum elevation: 1,620 metres

What the Monte Grappa lacks in gradient – an average of 5.4 per cent – it makes up in length at 24.1km. The climb is broken up by two plateaus, which will come as a welcome respite for the riders as they spend around an hour tackling it.

Then it is a plummet down the other side to face the 2017 race's final big ascent of Foza, the last chance for climbers to make a mark before the decisive final time trial into Madrid the following day.

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.