Changing of the guard: Meet the Great Britain track cycling coaches chasing gold medals

British Cycling replaced all four track head coaches last year. Here's how they're masterminding a path to Olympic titles

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This feature originally appeared in Cycling Weekly magazine on 1 June. Subscribe now and never miss an issue.

Four times a week, on the forecourt of Buckingham Palace, one of the country’s oldest ceremonies takes place. It starts with the rattle of a snare drum. Then, to the tune of the bearskin-topped regimental band, a group of guards marches slowly into the royal grounds.

They move in perfect symmetry. Upon arrival, the captain of the Old Guard hands over the palace keys, and passes on the protective duty. The ceremony lasts no longer than 45 minutes. By lunchtime, the throngs of tourists have dispersed, and the New Guard stands proudly, as still as statues.

Last year, in the space of six months, British Cycling overhauled its fleet of senior track coaches. There was no pomp or pageantry, just a handful of press releases, as the New Guard took up their posts. In came Ben Greenwood and Cameron Meyer to head up the men’s and women’s endurance programmes, while Jason Kenny and Kaarle McCulloch did the same on the sprint side.

A few changes after an Olympic cycle is fairly typical, but for head coaches of all the senior squads to change is not. And with just three years separating the Tokyo and Paris Games, this build up is anything but typical.

Between them, the four coaches have 12 years of coaching experience, but consider that nine of them belong to Greenwood, the men’s endurance coach. Meyer, Kenny and McCulloch, all former world champions on the track, joined straight from retirement. The national federation took a gamble on them. And it seems to be paying off.

British Cycling’s success, at least in the public eye, has often come down to one simple metric: Olympic medals. Though Tokyo crowned new British champions in BMX and mountain biking, the track medal haul didn’t reach the squad’s high standards, with half as many golds won compared to Beijing, London and Rio.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

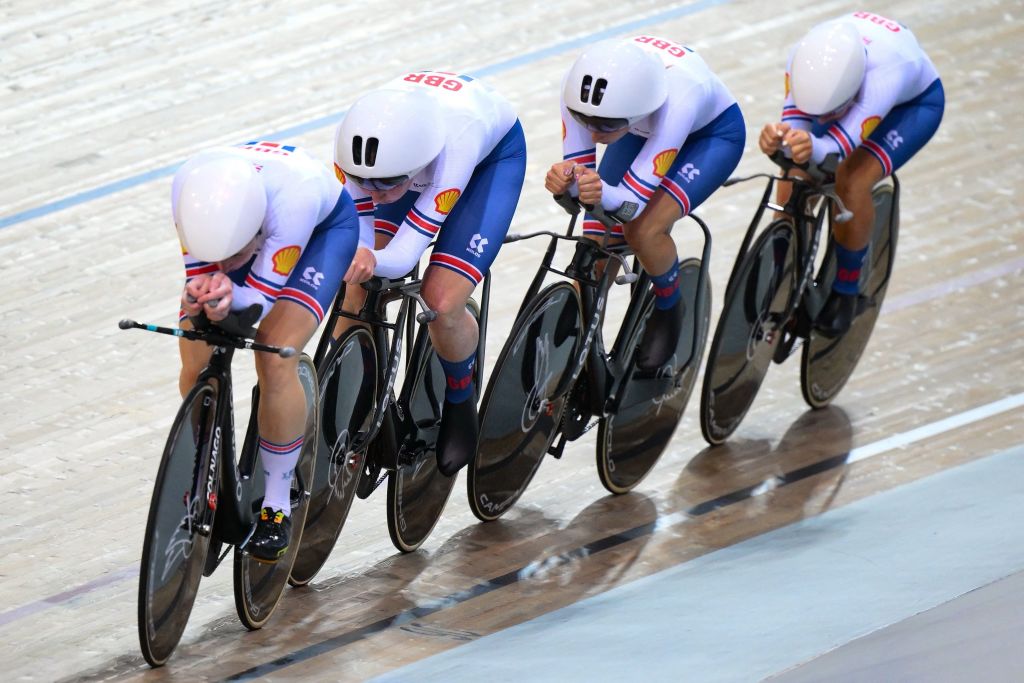

One of the titles that fell was the men’s team pursuit, an event they had won at each Games since Beijing 2008. “I’ve seen the ebbs and flows,” says Greenwood, who took over the role of men’s endurance coach in March last year. “I’ve seen us be top of the world in the team pursuit, and then seen it slightly drift away, after 2018. Your primary focus is the team pursuit to start with, as endurance coach, that’s the one you build your squad around. There’s a pressure to perform, but it’s just about breaking it down into its component parts. It’s overwhelming otherwise.”

Himself a BC academy rider, claiming an under-23 national title, Greenwood transitioned to coaching in 2014 and rose through the ranks from BC’s junior squads. A glance across at him inside the track centre shows a relaxed character, focused and level-headed, never one to raise his voice.

So it came as a surprise to see him jumping for joy when, just six months after taking over, he guided his team pursuit quartet to victory at the World Championships in Paris last October.

“I think it was just a realisation that the work we’d put in together had paid off,” Greenwood says. The world title came a year after a disastrous ride in Tokyo, which ended in last-minute substitute Charlie Tanfield losing contact and being rear-ended by the Danes.

“To come back from that Tokyo experience, where we literally ended up on the floor, to this, I think it gives us tremendous hope and optimism,” Greenwood says. “Obviously we’re aiming to win the Olympics and working towards that, but maybe it didn’t feel like we were going to get this far in six months. My reaction was like, ‘Oh, we’re already on par now.’ We’ve only done the first part of our project. We’ve got more to give.”

At the start of this year, Greenwood drove to Newport for the National Track Championships, together with the new women’s endurance coach, Meyer.

It was the first time the 35-year-old Australian had visited Wales. “All the way down, he was like, ‘How are we going to know we’re in Wales?’,” Greenwood laughs, “and I was like, ‘Well, we’ll see the sign and all the street names will be in Welsh’. He was like, ‘But how do we know? Will the scenery change?’ He was very excited.”

The excitement came in what had been a whirlwind four months for Meyer, who as a rider spearheaded the Australian men’s track squad for over a decade. Since calling time on his career last September, retiring as a nine-time track world champion, Meyer has barely had time to settle down. “It’s been full on,” he tells Cycling Weekly, but stresses the GB job was “too good of an opportunity to pass up”.

Despite his coaching inexperience, Meyer felt unfazed about the transition from athlete to trackside staff. “It’s just doing it with my legs on the ground, rather than on the pedals,” he smiles. “The way in which I look at it is that the understanding of what it is to be an athlete, we [retired pros] are very current with that. So the relationship that we can build with the current riders having been an athlete ourselves, just coming from retirement, I think it’s quite strong.”

To smoothen out the Australian’s career change, British Cycling has a support network around him, including a physiologist, a performance strategist and experts in psychology. Still, he explains, the first six months have been a “steep learning curve” for him.

“There have been those challenges that I didn’t have expertise in,” Meyer says. “[For example], it could be around female training, and the way in which the body of a female works differently to the men. I’ve been in men’s teams my whole life.

“We’re definitely still in that early stage of building the relationship between coach and riders. I feel like the energy that I’ve brought, the new ideas that I’ve brought, have been really well received. I really feel we’re in a great spot going into the next Olympics. I think we will be really competitive to try for three gold medals.”

When Meyer joined he was met by a familiar face - and accent - in the coaching ranks. Six months prior, former Olympic bronze medallist McCulloch took over the women’s sprint squad, arriving from Australia with her life packed into four suitcases.

Like Meyer, her coaching experience was minimal. “I was a little bit nervous coming in,” the former sprinter explains. “I had only done coaching with masters athletes and juniors beforehand, then [I was] going straight into this level again. I feel like I’ve really taken it in my stride, and I’ve had a big impact on my group. I’m really enjoying it professionally. I feel like I’m thriving.”

McCulloch’s Olympic hopefuls concur. Twenty-year-old Emma Finucane, holder of four British track titles, has reached new heights under the Australian’s tutelage. “She’s definitely brought a different light to coaching and sprinting,” Finucane says. “Her ideas are amazing and I really trust her. She’s very process driven, which I prefer, because I feel like I used to think of the outcome and not of how to get there. I used to be like, ‘I want to win’, not really knowing how.”

Women’s sprint coach McCulloch always tries to focus on the person behind the rider. “I was the sort of athlete that wouldn’t do anything else [besides cycling], and it broke me a little bit,” she says. “[My coach] would say things to me on a Friday afternoon, when we finished training, like, ‘Don’t come back to training on Monday without a story.’ At first, I was like, ‘What does that even mean?’ But he meant go live your life, go be a person.

“Now, the first thing I ask [my riders] when they come to training isn’t, ‘How are your legs today?’ It’s, ‘What did you do on the weekend? How’s your cake business going? Have you spray tanned anybody this week? How’s uni going?’ And then we talk about the bike stuff.”

When she first came in, the Australian organised a number of team-building activities to get to know her squad better. They’ve been out for one-pound tacos, taken part in a Samba drumming workshop and practised diving at a local swimming pool.

“If you don’t think about the person first,” McCulloch says, “you’re missing a really important piece of the puzzle.”

It’s this focus on the process that defines McCulloch’s approach to coaching. At the National Championships in January, she gave each of her riders an individual challenge, asking them to concentrate on aspects like positioning or timing, rather than results. In fact, in her first three months in charge, McCulloch stopped her squad from looking at their splits in training.

“There was a bit of kickback about that,” she laughs. “They didn’t like it at all. But what they’ve learned as a result of that is that they no longer, after training, go and look at their splits. They go, ‘Oh you know what, I didn’t hold the black line there, and that’s because I didn’t do this.’ For me, as a coach, I’ve done something there. I’ve changed the way they’re approaching it.

“My dream is that we’ll go to Paris, and I don’t have to do any coaching, because I’ve taught them everything they need to know. They’re on autopilot, and I can stand back and enjoy it.”

McCulloch’s appointment last February came as part of a 24-hour overhaul of the sprint squad coaches. The day before, with the dust having settled on Tokyo, seven-time gold medallist Kenny announced his retirement from racing, and career change to the men’s team head coach.

Kenny’s ability as a track sprinter cannot be understated. His medal record, topped up with a gold and a silver in Tokyo, makes him Britain’s most decorated Olympian, a status that wasn’t lost on Ali Fielding when he joined the squad two years ago. “In my first year training with him, I was a bit starstruck,” the 23-year-old says. “But as you get to know him, he’s just a chill, everyday, normal bloke, which is really cool. He’s really approachable.”

According to Fielding, Kenny’s transition from athlete to coach has been “seamless”. “It’s been really cool to go from that teammate environment to now him being my coach,” the sprinter says. “Just knowing who he is, and the pedigree he has as a rider, I think it brings in a lot of confidence, mainly. We’re in good hands.”

This confidence, in part, has led Fielding and his team sprint teammates to a bronze medal at the World Championships, and a silver medal at the European Championships. “You can’t ignore that it’s progress,” he says, and now he’s hungry for more. “Hopefully the bronze and silvers will turn into gold.”

The outlook, it’s clear, is positive. A year out from the Olympics, a feeling of optimism radiates from within the British team, one reassured by the recruitment decisions across the track squads.

Together with a talent pool that counts Katie Archibald, Ethan Hayter and Jack Carlin, GB’s New Guard are continuing their slow march towards Paris. They wear team-issue polo shirts, rather than bright-red tunics, and the ceremonies they’re used to take place in velodromes, not royal forecourts. By the time they reach the French capital, there’s a belief their athletes will be at the centre of the pageantry.

Tom joined Cycling Weekly as a news and features writer in the summer of 2022, having previously contributed as a freelancer. He is fluent in French and Spanish, and holds a master's degree in International Journalism. Since 2020, he has been the host of The TT Podcast, offering race analysis and rider interviews.

An enthusiastic cyclist himself, Tom likes it most when the road goes uphill, and actively seeks out double-figure gradients on his rides. His best result is 28th in a hill-climb competition, albeit out of 40 entrants.