After breaking half my torso in a car-bike collision, a sports psychologist makes sense of the emotional turbulence of a long recovery

Dr. Kristin Keim explains why being sidelined is so hard for athletes and what you can do now to be better prepared when injury strikes.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I’m pacing around my office as I dial her phone number. Six months into my recovery from a car-bike collision, my restlessness has reached a fever pitch. It’s been a long road, and patience is not a virtue I readily possess, but life is a relentless teacher.

This hadn't been the first time a car had taken me out. But, this time, the injuries were significant. A driver in oncoming traffic turned across the lanes at speed, and I had but a split second to react. I was in a bike lane. I had a green light. I even had bike lights flashing though the sun wouldn’t set for another hour. He just hadn’t seen me – sun in his eyes. I glimpsed him from the corner of my eye just in time to grab a handful of rear brake, forcing the bike to skid sideways and avoid a full-on T-bone. Still, the impact was unforgiving. Five broken ribs, punctured and collapsed lung, hemothorax, multifocal pulmonary lacerations, a bruised jaw, a banged-up elbow, and yet another concussion. I was in the trauma ward for three days, and everyone said, ‘I got lucky’.

But luck wasn’t on my side when it came to the recovery. Maybe I was ignorant, maybe the doctors' cautionary words— “traumatic”, “significant”, “it's going to take time” —fell on deaf ears. It's not like I hadn't been injured before. Broken bones only take 6-8 weeks to heal, right? I figured I'd be back on the bike in no time.

Yet, six months later, I’m calling Sports Psychologist Kristin Keim because I was struggling and knew others could be, too. My recovery process has been a series of ups and downs, from 20-minute recovery sessions on the Wattbike to three-hour gravel excursions and right back to 20 minutes on the Wattbike.

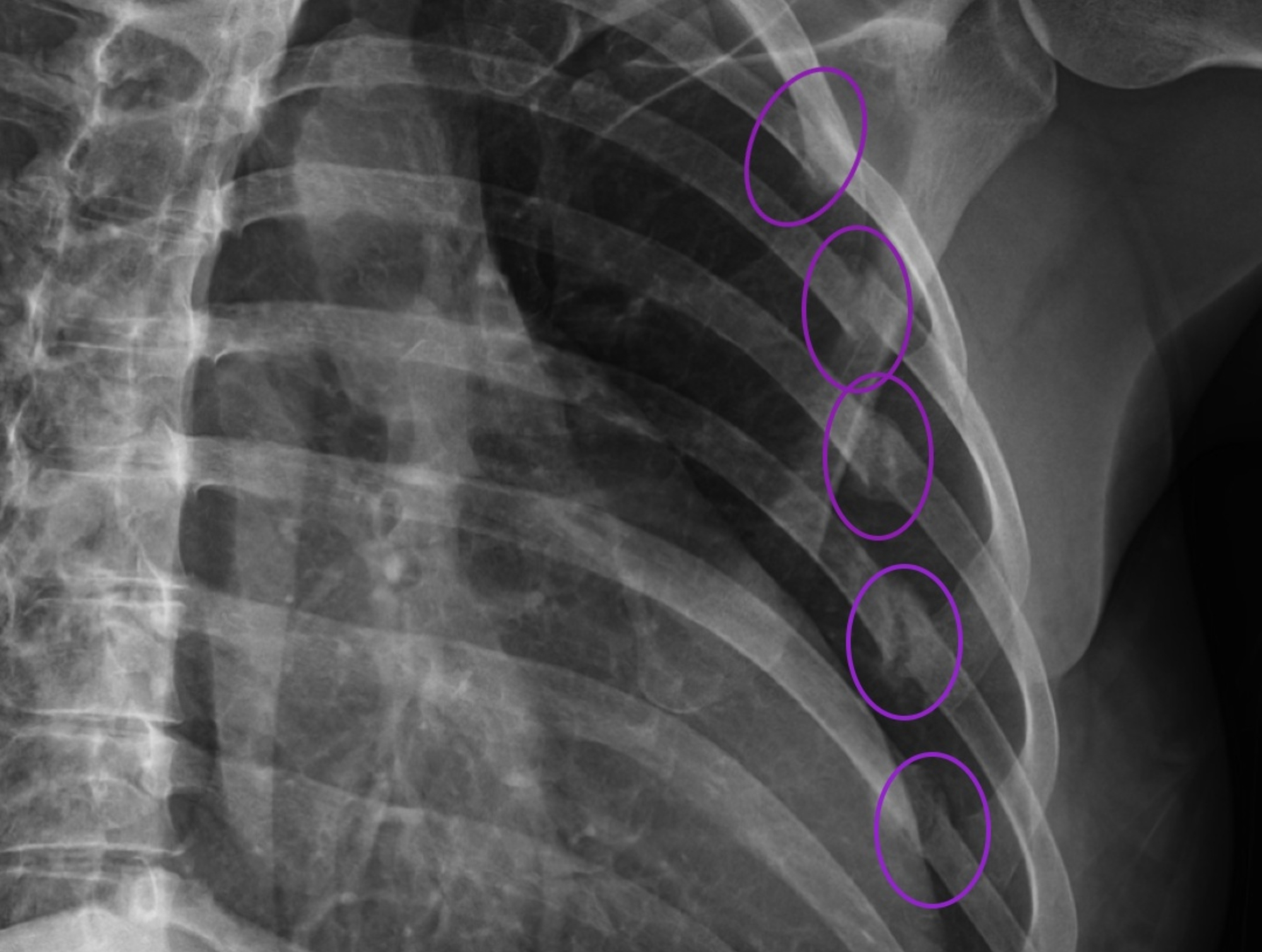

Every time I went in for imaging, the news was bad. The fractures stubbornly refused to heal. Four months into the whole ordeal, my ribs still weren't even touching yet. I’d gotten back on the bike by then, albeit in some pain, but until the bones were making contact on either side of the fractures, the doctor’s orders were “complete rest” and “total babying” of the torso. No biking. No running. No yoga. No lifting. No physical therapy. Walking was about the extent of movement allowed.

The ribs still broken four months after the collision

As a lifelong athlete, I wasn’t coping well with the loss of that steady stream of endorphins, the disruption of routine, the loss of fitness, weight gain and impact on my social life. By far, the psychological challenges of injury were worse than the injuries themselves.

Being an endurance athlete, whether a hobbyist or a professional, requires significant mental toughness. Resilience and stamina are essential to push through physical pain and fatigue. Focus, concentration, discipline, and self-motivation are critical to putting in the work and reaching one's goals.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But at the same time, is there not also a weakness there? We're so used to getting a steady dose of endorphins and dopamine that when it's suddenly taken away, we come apart. I certainly did at times, and I know my experience is a common one.

Emotions, especially anger, frustration and restlessness, are usually, wonderfully, suppressed by exercise. When stagnant, the emotions ran high.

As cyclists, we risk putting all our eggs in one (bike) basket, so to speak. I know I’m not alone when I say that cycling is my happy place, my therapy, my meditation, and my physical and mental outlet for, well, everything. It's not pretty when that's taken away all at once, without warning, when injury strikes.

Unfortunately, injury is inevitable. All athletes deal with being sidelined at one time or another. So how does one manage the mental and emotional turbulence of being injured and unable to do the thing we love most? Better yet, how does one prevent slipping into an unhealthy mental state to begin with?

This is where Dr. Keim comes in. A longtime sports psychologist, I got to know her when she worked with the likes of former U.S. national road racing champion and Giro d’Italia Women winner Megan Guarnier. In addition to her professional expertise, when it comes to being sidelined, her insights come from a place of deep understanding. She herself has been struggling with a severe chronic illness that has seen her unable to live her life to the fullest for years.

When she picks up the phone, her South Carolina drawl is warm and friendly, and her laugh comes easily.

“You’ve come to the right place. I really feel like you have to go through sh*t to really learn significant lessons. I’ve been there and I think that you’re going through it right now, and that’s an opportunity for you,” she affirms.

Why is being sidelined so hard for athletes, professionals and enthusiasts alike?

“It’d be easy to say that the lack of cycling is making you feel this way, but in reality, it’s the lack of exercise, being outdoors, sunlight, friendship, doing something you're good at, and the happy hormones, “ Keim states, highlighting in one brushstroke that the difficulty for athletes to cope with injuries stems from multiple interconnected factors.

A big part of these factors is chemical. Endorphins, dopamine, serotonin, endocannabinoids, cortisol—regular exercise has a big impact on hormones and chemicals in the body. Many of these are associated with mood and feelings of well-being. The sudden cessation of those hormones can lead to withdrawal symptoms, including mood swings and depression.

“Addiction is addiction, and athletes are 100 percent addicted to that steady stream of happy hormones,” Keim states.

Additionally, cycling crashes frequently result in concussions, and "the relationship between traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and depression is well-documented," Keim notes. If you're dealing with a head injury, depression symptoms can be intensified by both the post-concussion effects and the depressive feelings caused by the loss of exercise and routine.

Serious injuries also come with pain and discomfort. Especially during a long recovery period, the constant pain and physical limitations can become a mental burden, making it hard to stay positive and motivated.

This is amplified by the loss of routine and daily structure, which can make athletes feel lost. While mental toughness helps athletes push through physical challenges, sheer willpower won’t heal the body faster. The need to rest and recover may feel like a weakness. What’s more, the recovery timeline for injuries can be unpredictable –as I so rudely discovered– which may lead to frustration and anxiety around making one’s return.

Part of the struggle, too, is that for many athletes, their sport is a core part of their identity. Being unable to participate can lead to a sense of lost purpose and self-worth, as well as isolation. “For many, that’s the biggest piece and perhaps the toughest –to learn to appreciate who you are outside of your physical form or your job,” Keim says.

And then, there’s the isolation. Cycling can be a very social activity for many. Being sidelined and away from your usual riding buddies or teammates can lead to one feeling disconnected and lonely.

“There's nothing like being in a hard place to really understand who your friends truly are,” Keim says soberly. “Especially during a long recovery. Like, who’s reaching out to you after 3 months or a year?”

How can athletes cope with being injured for a long time?

Rook watches the UCI World Championships as she recovers from her injuries

So, with all of these drawbacks of missing out on regular exercise and the lifestyle that comes with it, how can athletes cope?

“There is no cookie-cutter strategy for anyone,” Keim states. But fortunately, there are some steps one can take, and it starts with prioritising rest and recovery.

“The tricky thing with being injured is that it’s all compounding. Not only are you not getting to do your activity of choice, you’re probably not sleeping or eating well,” Keim stated. “Recovery is something you have to actively, cognitively, work on. If your job is to do your sport, then now it’s your job to heal.”

This means ensuring you get adequate sleep and proper nutrition and letting the body do its thing. Once your body is stable and recovering, you can make a plan to address the mental and emotional component of recovery, but Keim advises allowing yourself to feel your feelings first.

“Allow yourself to be angry, frustrated, anxious, depressed. Allow yourself to feel those feelings and don't overanalyse them because the worst thing is to try to not feel them and just suppress them,” Keim recommends.

“You got hit by a car! You have every right to be f***ing angry and upset. So drink a glass of wine (medication-permitting) and throw the bottle against the wall if that makes you feel better. Feel it and get it out of your system.”

When it comes to recovery, Keim says to break down the recovery process into small, achievable goals and to celebrate progress, no matter how minor, to maintain motivation and a sense of accomplishment.

“Start with something simple like sleep and keeping a diary. What little things are you doing today to make it better?” Keim says.

In the meantime, don’t forget to connect with your community. Stay in touch with your social circle can provide emotional comfort and keep you involved in the sporting community. Chances are, some have been through some forced downtime themselves.

Finding alternate sources of those happiness hormones

When it comes to feeding the mind with those chemicals it’s missing, you actually don’t have to look far to find replacements.

“Serotonin, dopamine, endorphins, oxytocin – all those things promote happiness and reduce your depression and your anxiety - where are they coming from? Even injured, you can still go outdoors, you can connect with friends, cook a nice meal for your partner, paint, make music, enjoy a good movie –it won’t give you the same big hit as exercise, but you can get your mood enhancing mojo in many other, small ways,” Keim assures.

For me, I struggled hard without those ‘big hits’ Keim mentions. Previously when I broke a wrist or blew out my MCL, I could ride the trainer or swim or work on parts of the body that weren’t hurt. The torso injuries –even after my chest stopped gurgling blood and I got my lung capacity back– prevented me from most physical activities, and walks and hiking just weren’t cutting it. It took a while but I realised the sense of accomplishment was missing, and so, going somewhat restless, I repainted the kitchen and every door in the house (which probably wasn’t great for the torso either but it satiated my need to feel productive outside of work.)

Keim laughs at this textbook behaviour.

“For many athletes, it’s cleaning. They get fixated about cleaning as it gives them a sense of accomplishment and it gives purpose to their downtime from sport,” Keim shares.

“But that’s just it: you find new ways to get that chemical hit. If you’re used to going on a long ride with friends –endorphins– and get a cookie –dopamine–afterwards, then go for a walk and make a coffee stop. It still hits those endorphin and dopamine areas, just to a lesser extent.”

What to do now so you’re better equipped when you may become injured later

Injury can come at any time, so what can athletes do now to ensure an easier time during the recovery period?

“As you’ve realised, the bike has become a crutch for many things in your life. When the bike is your main source of joy and your only outlet, it almost becomes your kryptonite as well,” Keim points out. “You haven't trained your brain and your body to find happy hormones and pleasures in other things.”

“No matter if you're a pro athlete or you just love to train and ride, diversifying and not putting so many eggs in your basket is very important.”

Keim says that this rings especially true for professional athletes, as their career, livelihood, and self-worth tend to be so deeply tied to their sport.

“With my clients, the minute they hire me, that's the first thing we start talking about. You have to find other things that give you meaning and purpose and joy besides riding your bike or swimming or gymnastics or ice skating or whatever the hell their job is,” she shares.

Her biggest piece of advice? Learn something new every year.

“Take a class, learn a language, learn to cook, take up hiking or yoga, start a home project, just find other activities that make you happy or are engaging and challenge you in new ways,” she says. “That doesn't mean we're trying to replace cycling or running or what have you, it’s about challenging yourself in ways that are not 100 percent tied to physical activity. Pro athletes, especially, have to do that to be good at their jobs and endure the challenges of professional sports. But even for hobbyists, it prevents them from going into a deeper depression when injured.”

Subscript

Back on the bike and happy about it!

Keim’s advice to me specifically was to give this period in my life meaning and purpose and to share my story when I was ready. And so, I’m sharing my story with the hopes that someone gains something from it—if only to make someone feel seen and less isolated in their experience.

At the time of writing this, I am 11 months into my recovery journey. I’m still going to physical therapy but mostly, I’m back to normal – albeit out of shape. I’m perhaps a tad more wary of cycling on the road but I certainly will never take the joys of riding my bike for granted again. If nothing else, this recovery period made me realise that riding a bike is an absolute privilege, even if it’s raining sideways. But perhaps, don’t make it your be-all, end-all? Living by Joop Zoetemelk’s famous adage, “the bike, the bike and nothing but the bike,” won’t serve you well when injury strikes.

Cycling Weekly's North American Editor, Anne-Marije Rook is old school. She holds a degree in journalism and started out as a newspaper reporter — in print! She can even be seen bringing a pen and notepad to the press conference.

Originally from the Netherlands, she grew up a bike commuter and didn't find bike racing until her early twenties when living in Seattle, Washington. Strengthened by the many miles spent darting around Seattle's hilly streets on a steel single speed, Rook's progression in the sport was a quick one. As she competed at the elite level, her journalism career followed, and soon, she became a full-time cycling journalist. She's now been a journalist for two decades, including 12 years in cycling.