Why stress can make you fat - and what to do about it

Can't lose weight? Or maybe you have lost some but can't shake off the bit of a tummy that crept up on you over the years? Do those scenarios sound familiar? If so it could be stress that's causing the problem, and some of your training might even be working against you

Most people are familiar with the fight or flight response that was crucial in keeping our ancestors alive when they hunted big, dangerous animals and tried to evade even bigger and more dangerous ones.

Fight or flight is still crucial today if you are in a life-threatening situation, and it's a big help in competitive sport, but such moments of acute stress are thankfully quite rare.

The thing is fight or flight can't distinguish between short bouts of acute stress and long-term chronic stress.

>>> Detraining: The truth about losing fitness

Whether you are being chased by a bear, stuck in traffic or worrying about your finances, fight or flight still kicks in. Not quite as sudden or intense in the last two scenarios, but it lasts much longer.

Stress response is controlled by your brain, specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, working with your adrenal glands.

>>> Is your adrenal system making you tired?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The process is called the HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis), and when your brain detects a threat it sends a message straight to the adrenal glands, which in a split-second releases a flood of adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol. This gets pumped around your body, pepping everything up so you can either fight hard or run fast.

And that's where the problem lies because in normal life there isn't much need to run or fight, but modern stresses, like being late for a meeting or facing a deadline, still provoke the same fight of flight response.

To a lesser level, but it happens over a far longer period of time. As we don't face peaks of stress on a day-to-day basis, it's more like long-lasting undulations of stress that are the problem, and fight or flight didn't evolve to meet constant stress.

>>> Seven easy steps to avoid winter weight gain

In fact it can damage your health unless you are aware of it and do something about it, and at the very least it can work against your efforts to lose fat, especially fat around your middle, whether you are male or female. The latter is worth noting because belly fat was seen as a male-only problem in the past. It's not.

Understanding fight or flight

In a normal fight or flight response adrenal hormones cause the liver and muscles to release their stores of glucose, while muscles let amino acids go and fat breaks down into glycerol because the body can use amino acids and glycerol as fuel.

The intense physical effort that should follow this response triggers the release of testosterone and human growth hormone (HGH), which promote muscle repair and push fuel use back towards fat.

The net result is a restoration of the body's status quo, plus if nutrition is adequate there will be strengthening so your body is better equipped for the next fight or flight. It's a bit like the optimum way to train, which is worth bearing in mind as you read on.

>>> Always hungry? Here are 5 reasons why

Overall, normal fight or flight is a health-boosting process, but the response to chronic stress is slightly different, and it's definitely not healthy. Glucose release happens in the same way in response to chronic stress, but fat is spared and more amino acids are taken from muscle tissue instead.

The final nail in the coffin is that because chronic stress goes on for longer you don't get the repairing testosterone and HGH release because you haven't done enough physical activity to trigger it.

>>> Nine ways cycling changes when you’re over 40

And there's more bad news. Chronic stress without the release of physical activity causes a sharp rise in cortisol levels, which can change our physiology, especially in relation to hunger and cravings. Cortisol increases hunger and promotes the desire for high-calorie foods. It can also cause muscle tissue to be lost from arms and legs, and fat to be stored in the abdomen, which is a major health concern.

Find out about training zones

There is an answer

Belly fat, and even worse, visceral fat - that which is deposited around the organs of your abdomen - is connected to heart disease. High levels of cortisol causes blood sugar to rise, so insulin is produced to control this by turning the sugar to fat, and it's the high levels of insulin that causes the build-up of visceral fat.

>>> Five steps to lower your daily sugar intake

But it's not all bad news, because exercise has a trump card to play. When we talk about high levels of cortisol what we really mean is levels that are high relative to testosterone and HGH production.

Cortisol is a catabolic hormone, it tears down muscle tissue, whereas testosterone and HGH are anabolic; they build muscle.

So if you can boost the testosterone and HGH side of the relationship while controlling the causes of high cortisol production, ie stress, you will get fitter, stronger and leaner all in one go.

How to do it

Testosterone and HGH production are stimulated by sleep, adequate protein intake and intense exercise. This provides a practical solution to the problem of 21st century stress.

We could advise you to lower your stress levels, and you should try, but we all live in the real world and there are undeniable demands in it that cause stress.

>>> How to resume your training after a break

The best way to reduce the harmful effects of this stress, and to lose the belly fat it can end up giving you, is to boost your testosterone and HGH levels.

The single most effective way of doing that is with high-intensity exercise. Short duration interval training, from out and out sprints to interval lengths of about three minutes, is a very effective way to boost testosterone and HGH levels. So is weight training.

>>> Hill intervals: improve your climbing

If you combine two high-intensity interval sessions a week and at least one weights session, with an adequate intake of protein (around 1.5 grams per kilogram of your body weight per day) and good quality sleep, you will counter the effects of high cortisol, defeat your belly fat and improve your health.

At the same time you could cut the number of long, steady training sessions, as these can cause high cortisol and low testosterone/HGH levels too. One or two a week is enough, certainly until your fat levels fall.

Avoid these foods

Determining visceral fat

If you are otherwise thin but have a belly you could be storing levels of visceral fat and suffering from stress fat syndrome. The best way of determining your visceral fat level is by using weighing scales that determine fat levels.

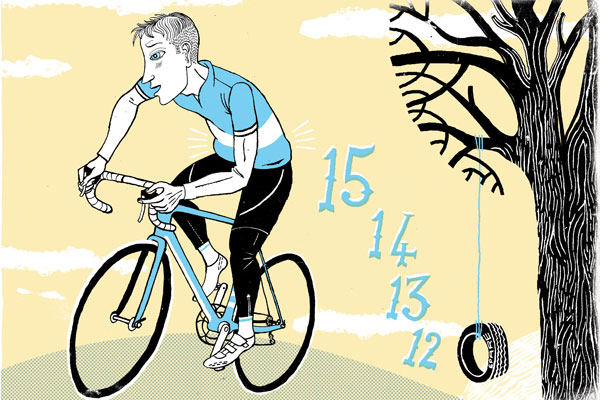

As well as a total fat percentage they will give you a visceral fat rating. In the case of one of the most popular brands of scales, Tanita, the visceral fat rating will be a number between 1 and 59, with the range of 1 to 12 being healthy and any figure between 13 to 59 signalling an excess of visceral fat.

>>> Listen to your body: don’t ignore the warning signs of injury

These scales work through bio-electrical impedance, where low-level electrical signals are passed through your body, which the various constituents resist at different strengths. The scales record this and produce numbers that represent what your body is made up of. Many fitness centres and gyms have them, and they are reasonably inexpensive to buy and very useful if you are training to lose weight.

The scales aren't pinpoint accurate, but as long as you use the same machine and follow a repeatable protocol they provide very useful feedback.

Seven steps to beat stress fat

1 - Never miss breakfast but also try to increase the percentage of protein in it. Cortisol levels rise if you don't eat first thing, and protein stimulates testosterone and Human Growth Hormone (HGH) production, which is what you are after to counter cortisol. Protein also makes you feel fuller for longer and prevents the spikes of glucose in the blood that a high-carbohydrate breakfast causes.

2 - Do two intensive interval sessions per week, either sprints or intervals of up to three minutes. If you want to do longer intervals sessions or a longer ride, do a few sprints at the beginning as part of your warm up.

3 - Train with weights at least once per week. Get expert advice on how to do it and use a low rep/high load principle to get the best effect. Boost your weight training by consuming half a protein shake 30 minutes before it and the rest straight after, and do no other training, or only light training, on your weight training day.

>>> Six winter cycling exercises for strength and conditioning (video)

4 - Try to get seven to eight hours sleep per night. It won't always happen, but try for it. HGH secretion is highest just after you fall asleep, so if it's possible to take a daytime nap it will give you an HGH double shot. Console yourself with the thought that if you have to get up in the middle of the night to attend to a restless baby, as soon as you drift off the HGH comes on again.

5 - Eat protein with each meal and split your day's total calories over five instead of three meals, so long as they are fairly equally spaced. And eat slowly and mindfully.

6 - Pure 100 per cent cocoa decreases the food cravings stress induces, so a cup of cocoa or a few squares of 100 per cent cocoa chocolate is medicine in this case.

7 - Don't let your training stress you; go for a walk at lunchtime instead of squeezing in another training session. Relax yourself by make walking part of your daily life.

Stress busting intervals

Turbo-trainers are perfect for these, but you can do them on the road too. Warm up thoroughly by riding progressively faster for 10 to 20 minutes. Do 10x 20-second to one-minute efforts going as hard as you can for the duration of the effort.

The rest intervals of easy spinning should be three times the duration of the interval.

If you want to do longer intervals try four to six two-minute efforts with two minutes of easy spinning between each, or three to five three-minute efforts with three minutes of easy spinning between each interval.

>>> Turbo training: Improving performance

Then ride easy for the remainder of what should ideally be a one-hour session. Initially you should focus on slowly bringing your body up to speed during the warm-up. Then during each interval focus on sustaining the effort equally right through to the end, and on maintaining a perfect pedalling style while doing so.

Between each interval, shift to a low gear and use the words ‘spin' and ‘relax' to help you recover. Then for the final easy part look around and enjoy being where you are. If you do this session on a turbo trainer, create a playlist of music that will help you achieve the three mind states.

The comfort eating gene

In an effort to find reasons why some people reached for the biscuit tin during times of stress, Professor Alon Chen, working on the neurobiology of stress at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, discovered a gene that controls the production of a protein called Ucn3.

It's produced by certain brain cells and is known to play a role in regulating the body's stress response. The protein changes feelings of hunger and satiety, increases the desire for sugary food and throws a switch in muscle cells from burning fatty acids to glucose.

Professor Chen says: "These responses are good when you have to cope with an event like meeting a lion - the metabolic changes help you burn more glucose - but the gene needs to kick in only at that time," implying that anybody with the gene who is in a state of constant stress might not be able to control what they eat.

This tallies with earlier work at Dundee University which suggested two thirds of the population carry what they labelled ‘junk food genes' and on average eat 100 calories more per meal than people who don't carry the gene.

It's not good news, although Professor Chen hopes to develop a drug that works against the gene. However, knowledge is power: if you know you carry the gene you can at least develop strategies to cope with it.

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast